Shirley Yao, Sabrina Meyn, Viktoria Hovhannisyan

The friendship dynamics that males and females form with the same-sex differ in how they bond homosocially: either vertical or horizontal. Homosocial bonds are those that are non-romantic social bonds between those of the same-sex. Historically, these two types of homosocialities are used to regulate how people perform gender. Vertical homosociality, also known as hierarchical homosociality, is relationally tied to males, and horizontal homosociality with females. Vertical is centered on building power socially, whilst horizontal captures non-profitable aspects of social bonds. Research has shown that heterosexual males tend to be hypersensitive to their sexuality being misinterpreted in homosocial contexts, whilst females are presumed not to be. This has been previously attributed to female homosocial bonds being defined as desexualized relations and their intimate relations as being friendly or as a sexual display for the heterosexual male gaze. However, in the literature there is room to explore female’s friendship and social dynamics and obtain updated information on male homosocial friendship dynamics by comparison. Using a comprehensive questionnaire that aimed to gather data on participant’s homosocial friendship dynamics, we found that both females and males exercise homosociality similarly.

*Disclaimer: Gender and sex are not interchangeable terms, as gender refers to something people do or perform socially, and sex is what you are biologically. The participants in this study identified their sex as either being male or female.

Introduction and Background

From “bros” to “babes,” males and females tend to have different friendship dynamics. The topics of sex, friendships, and homosociality has been widely studied. Homosociality is a phenomenon between people of the same-sex with a “nonsexual attraction” to each other (Bird, 1996, p. 121). Through a study to determine the type of homosociality practiced between males and females, we aim to better understand the friendship dynamics across sex. Specifically, our target population includes straight males and straight females in college who form close-knit homosocial circles, tracking homosocial situations where homosexual intentions may be incorrectly perceived within friendships.

Historically, homosociality comes in two strokes: vertical (hierarchical) and horizontal. Vertical homosociality is “a means of strengthening power and of creating close homosocial bonds to maintain and defend hegemony” and as a result, it has strong ties with hegemonic masculinity (Hammarén & Johansson, 2014, p. 1,5). Hegemony is related to structural social power dynamics. Hegemonic masculinity is built on an archaic conception of masculinity rooted in institutionalized practices that value males and devalue females (Bird, 1996, p. 1-2, Rose, 1985, p. 63-4). Horizontal homosociality is defined as being built on “emotional closeness, intimacy, and a nonprofitable form of friendship” and has strong ties to female homosociality (Hammarén & Johansson, 2014, p. 1,5). Most studies conducted that explore homosociality are focused on heterosexual males. There is little research on female homosociality, especially those that do not have a heteronormative foundation (Sanders, 2015, p. 887). In addition, data on male homosociality is outdated. Rose (1985) performed a study on cross-sex and same-sex preferences in homosocial bonds (p. 83). It was found that males and females have the same expectations in same-sex friendships, while expecting less help and loyalty in cross-sex or heterosocial friendships (Rose, 1985, p. 63). Friendship formation and maintenance were found to differ for same-sex and cross-sex friendships between the sexes as well (Rose, 1985, p. 63). Bird (1996) claims gender is relational – where a person will perform gender in accordance with either vertical or horizontal homosociality (p. 122). Bird (1996) also identified how hegemonically masculine ideals are perceived as being the socially ideal form of masculinity (celebrates emotional detachment, competition, and the sexual objectification of females) (p. 121). Studies have found that homosexual people can have their own language, especially specific vocabulary words (Kulick, 2000, p. 243). We will review data on the usage of homosexually charged nicknames between the sexes in results.

This study is a step towards more representational and up-to-date data on both male and female homosocial tendencies and in particular, friendship dynamics. Based on previous research, the foreground expectation is for the data to show that gender is relational, where, a person’s sex will predict the type of homosociality present in their friendship dynamics. In particular, males will overcompensate for their fear of being perceived incorrectly as having homosexual intentions, projecting an overly masculine persona and using linguistic features to create social distance. Comparatively, females will embrace the idea of receiving incorrect perceptions. They will prioritize emotional closeness in their friendships, and exhibit no particular linguistic behaviors different from their everyday conversations.

Methods

To test our hypothesis we gathered data from 16 college students, ages 17 to 25, which included 8 females and 8 males, 14 straight and 2 bisexual. We asked them to fill out a questionnaire that was designed to test their beliefs, lexicon, and conversational content as it relates to their homosocial friendships. We used multiple choice, short answer, checking boxes, and rating comfort levels on Google Forms to collect information from anonymous participants. The survey included five parts aiming to gather: biographical information, ideological beliefs (to test for horizontal or vertical beliefs), short answer questions directed towards the conversational content, a section directed towards investigating a person’s lexicon to see what phrases and nicknames are used to create or lessen social distance and a section directed towards investigating reactions to inappropriate/appropriate language use or behavior. Vertical answers emphasize emotional detachment, sexual objectification of females, sport, competition, and deny horizontal things such as gossip, feelings, etc.

Examples – An example of a question that was asked is the following: “friendships are important to my social standing” this question was intended to answer with either “yes” or “no.” A yes or affirmative to a vertically loaded question would result in adding a point to a person’s vertical homosociality score, and a negative would add a point to a person’s horizontal homosociality score, and vice versa for horizontally loaded questions. Examples of horizontally loaded questions would be: “being emotionally close to my friends is important to me” or “intimacy is important to my friendships.” In the short answer sections, horizontally loaded answers would receive a point per question, and same for vertically loaded responses. Comfortability scores over 5 for a particular type of question would result in a point being added as well depending on the question category.

Results and Analysis

Results

DEMOGRAPHICS

16 participants ages 17 to 25, 8 female, 8 male, 14 Straight, 2 Bisexual

IDEOLOGICAL

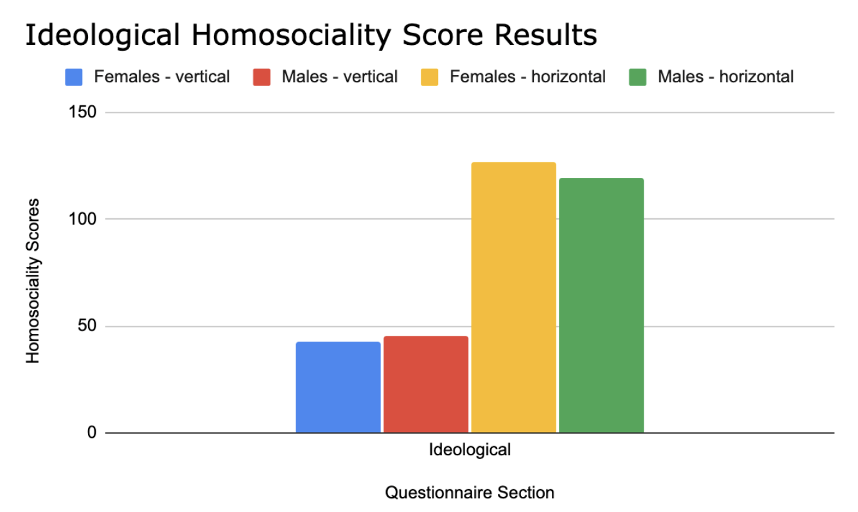

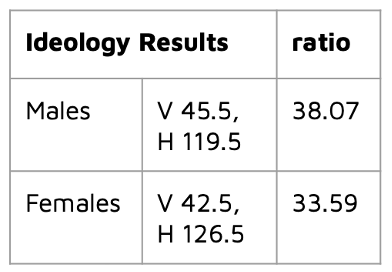

We found that both females and males are ideologically more horizontally homosocial leaning.

Examples of questions included: if friendships were important to social standing, maintaining the patriarchy, if it was acceptable to use friends as a means to an end, if they observed people in their homosocial circles discuss, disparage, or use the opposite sex to gain social status, as well as if they individually believed it was acceptable to do so. About ½ of participants observed this happen, but ¾ of the responses said they felt it was unacceptable. Surprisingly, over 90% said it was false that friends should not have romantic feelings for one another and friends should not have feelings in general for each other, and that it was true that being emotionally close was important.

FEAR OF MISINTERPRETATION OF SEXUALITY

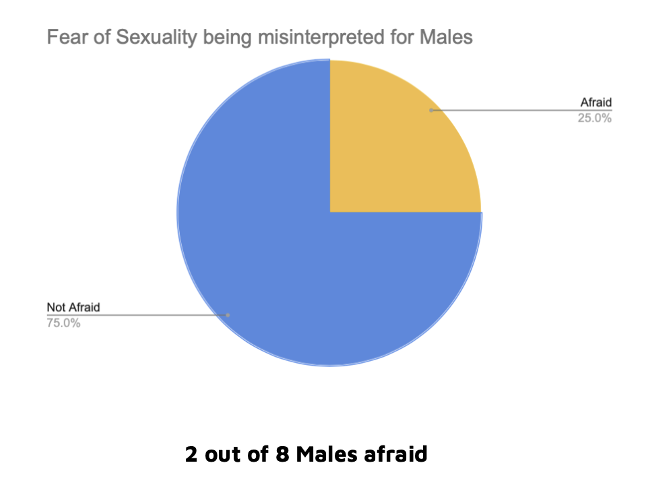

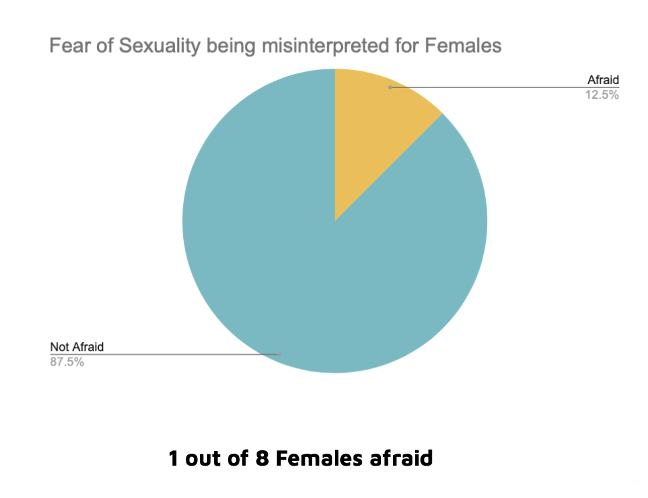

Ideologically speaking, 25% of the males surveyed are afraid of their sexuality being misinterpreted, and 12.5% of females are afraid of their sexuality being misinterpreted.

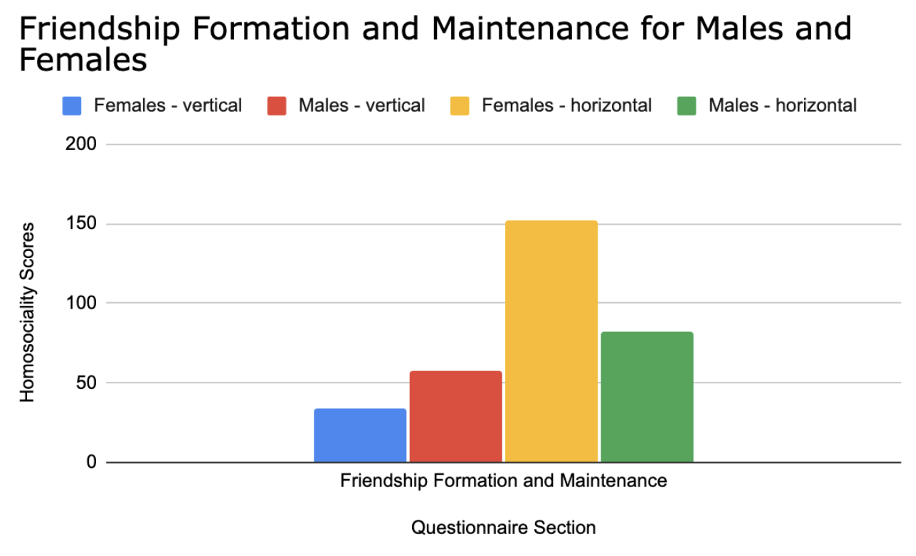

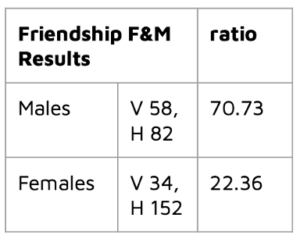

FRIENDSHIP FORMATION AND MAINTENANCE

Similar to the results of the Rose study, friendship formation and maintenance differed between the sexes. The homosociality scores for both males and females were overwhelmingly more horizontally leaning, but females were approximately 85.36% more horizontally homosocial than males.

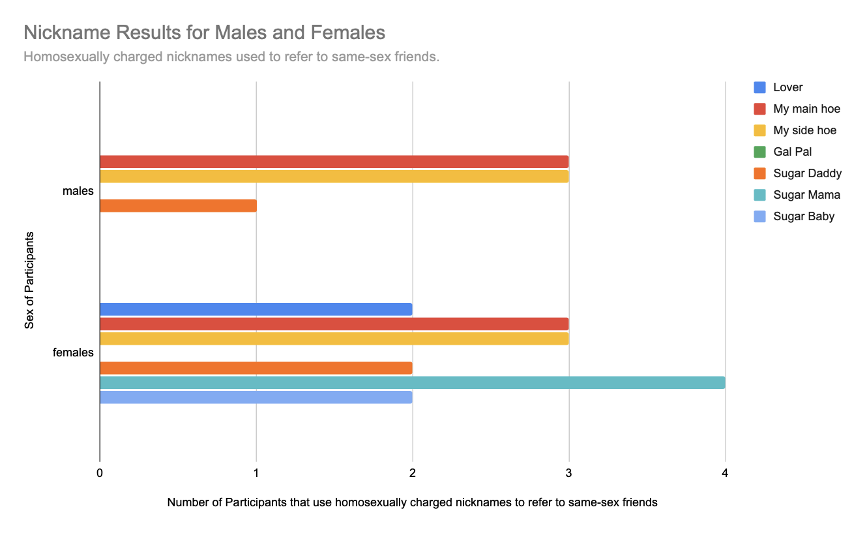

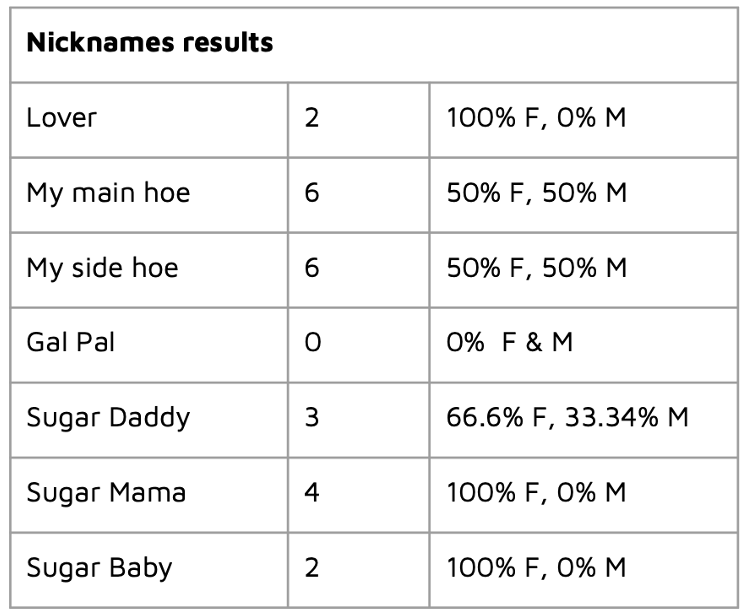

NICKNAMES

Although a percentage of males and females who are afraid of their sexuality being misinterpreted, we found females use more homosexually charged nicknames and pet names than males by approximately 39.13%.

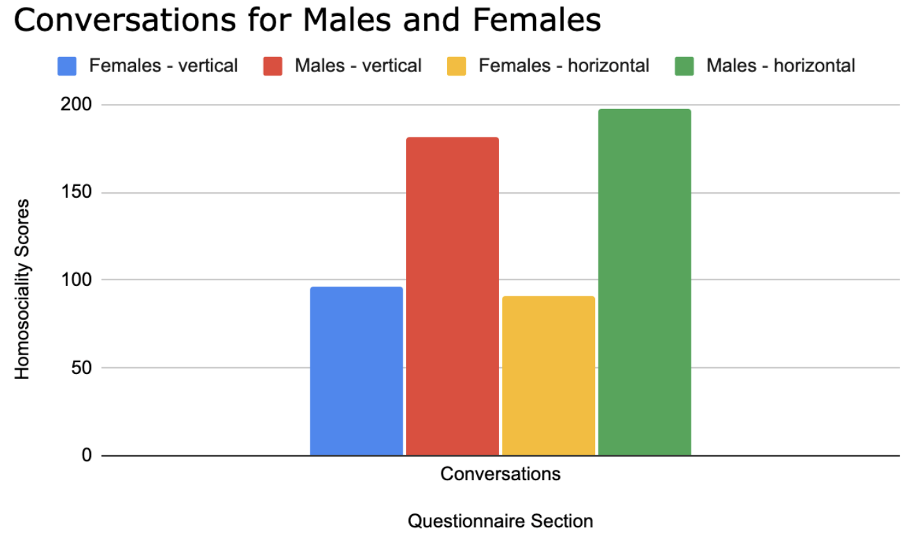

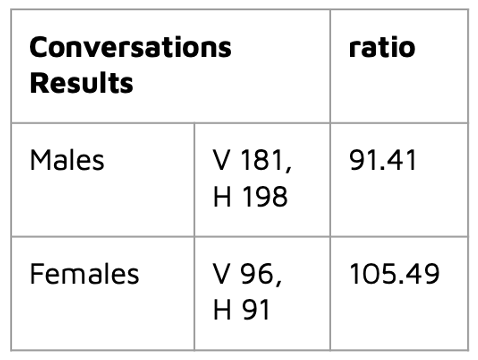

CONVERSATIONS (appropriate vs. inappropriate topics)

We found that both females and males are a combination of vertical and horizontal, and marginally lean one way or the other.

Examples – For conversations participants rated their comfortability and indicated if they did talk about a range of topics with their same-sex friends that ranged from: school, business, social status, sexual activities, sexual conquests or accomplishments, to test for vertical homosociality, to topics which do not make for a profitable exchange like gossip, feelings, saying “I love you,” worries, morals, etc. We also asked about topics they do not think are acceptable to be discussed with their same-sex friends and the responses ranged from nothing being off limits, to family drama, insecurities, sexual life, politics, religion, weight, romantic relationships, etc.

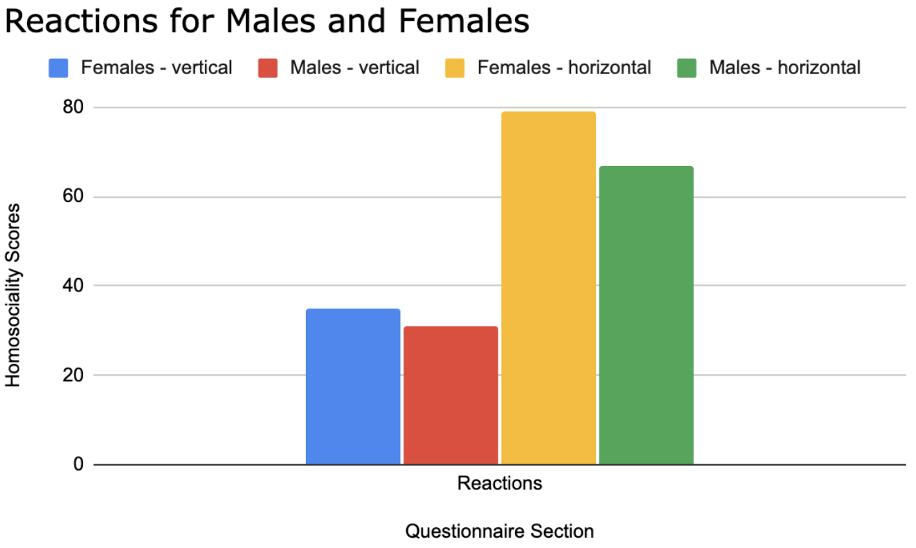

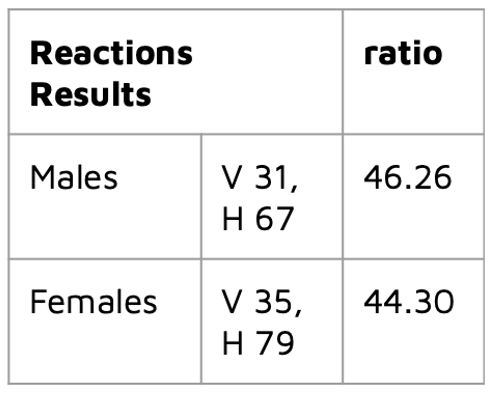

REACTIONS (to inappropriate topics and/or actions)

Here we were looking for their reactions to various topics and actions that would lead to a misinterpretation of their sexuality. We found that both males and females have horizontal homosocial tendencies in reaction to behavior which may be perceived as having homosexual intentions.

Examples – We asked participants to rate comfortability, and express what they might be met with or observe if any of the following topics or actions would come up: compliments, hugging, kissing friends, cuddling with friends, holding hands, platonic feelings for same-sex friend, romantic feelings for same-sex friend, actions/words which are perceived as having homosexual undertones, actions/words which may be perceived as having homosexual undertones, saying “I love you” to your same-sex friend.

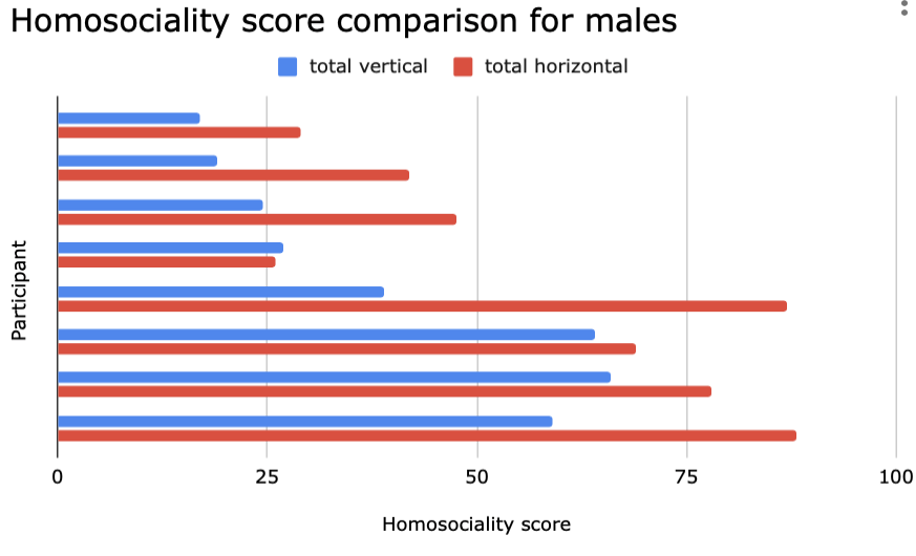

OVERALL MALE HOMOSOCIALITY SCORES

The majority of our male participants had horizontally leaning homosociality scores, while only one male participant was more vertical leaning by 1pt (approximately 0.037%).

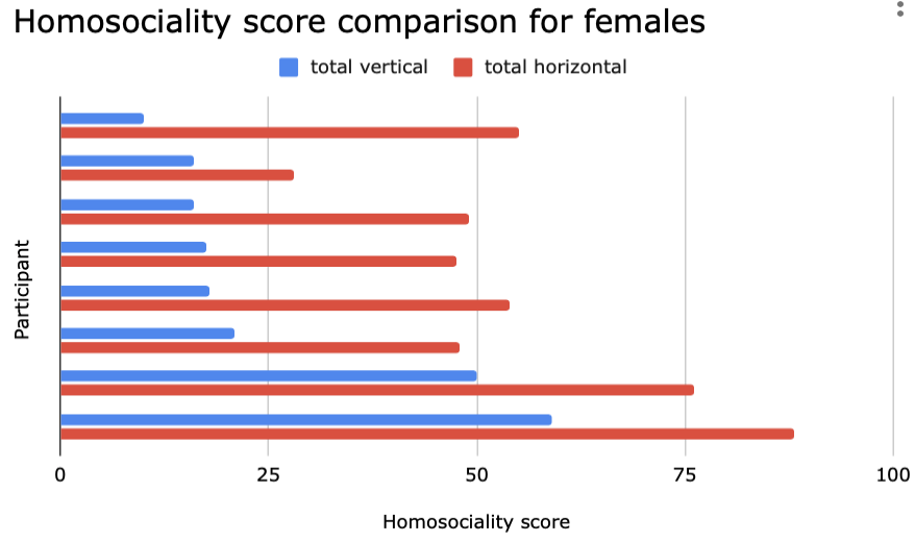

OVERALL FEMALE HOMOSOCIALITY SCORES

All of our female participants scored more horizontally leaning homosociality scores.

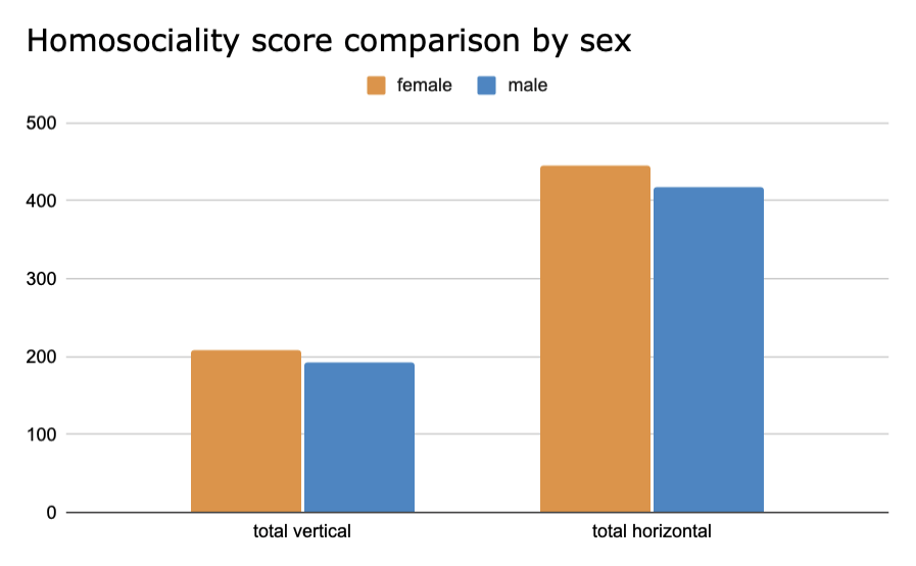

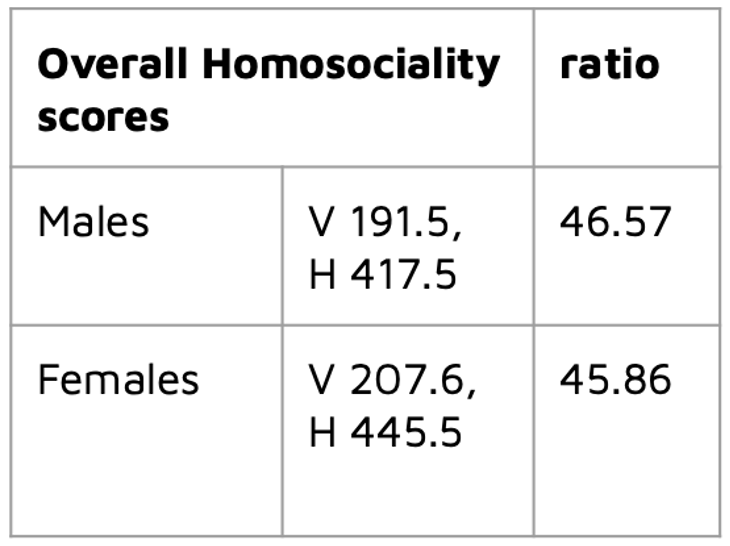

OVERALL HOMOSOCIALITY SCORE COMPARISON: MALES VS. FEMALES

Overall, females and males were found to be overwhelmingly horizontally leaning, with a combination of vertical and horizontal homosocial tendencies and beliefs. Their overall vertical scores are also similar, with females scoring approximately 8.4% more vertical than males, and 6.7% more horizontal than males, with a minimal overall margin of difference of 0.71.

Our results show that both females and males have a combination of vertical and horizontal homosocial tendencies and beliefs, with an overwhelming slant towards horizontal homosociality. What this means is that the homosocial tendencies of females and males are similar. Since they were found to be a combination, this means that females and males don’t just correspond to one kind of homosociality over the other. This disproves the idea that gender and homosociality are strictly relational since males did not score strictly vertically, and females did not score strictly horizontally.

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion

While sex does not determine the type of homosocial friendship present, it plays a factor in understanding different interactions within homosocial friendships. With no significant statistical difference between vertical and horizontal scores, gender is overall not relational, meaning horizontal and vertical homosociality scores do not reflect the predicted homosociality of males and females. In fact, both sexes have a relatively higher horizontal score compared to their vertical scores in total.

However, when looking into each of the four topics individually, observations about the different friendship dynamics arise – with areas worthy of further exploration. The most distinct difference occurs in the area of friendship formation and maintenance. With ratio score comparisons of 70.73 and 22.36, males and females are strikingly different when it comes to building and sustaining homosocial friendships. Comparatively, females are more likely to form and maintain friendships horizontally than males – using intimacy and closeness as their powers to reach out and establish connections. In the real world, males tend to strengthen relationships by participating in activities together, and females tend to do so by sharing feelings and talking about various things. Linguistically, females are also more likely to use linguistic features that are indicative of intimacy and closeness, reflecting horizontal homosociality through their everyday conversations. Through the use of specific lexicon such as the homosexually charged pet names of “sugar mama” and “sugar baby,” females are unafraid – and even embrace – the idea of their sexuality being incorrectly perceived.

Ideologically speaking, most males and females have similar ideological beliefs about homosocial friendships, with nearly identical ratios between their ideological vertical and horizontal scores. As the sample is composed of college and high school students, it is understandable for many to have a similar group mindset to find social circles and fit in. The COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated the isolation anxiety for many to feel eager to belong. The societal norm also values honesty and friendships and paints betrayals and loneliness as traits that should be avoided. The topic of conversational content also reveals similarity between males and females. Though females have lower vertical and horizontal scores compared to those of males respectively, the ratio between the two is still similar across sex, meaning males and females have similar shares of vertical and horizontal conversations. Looking into conversational content linguistically, many responses include talking about school and friends, regardless of gender, mainly because of the social setting within colleges to define conversational topics. It is interesting to note that females are more likely to talk about males, whereas males have a higher tendency to talk about careers and the future – further demonstrating the foundation of female homosexuality to be rooted on the exchange of intimate facts and truth compared to male homosexuality.

Last but not least, the examination of reactions to incorrect perceptions between males and females also prompt similar homosociality scores. However, as predicted, males are relatively more likely to be afraid of receiving incorrect perceptions regarding sexuality. Interestingly, 12.5% of the females surveyed are afraid of being perceived incorrectly in terms of sexuality – a higher percentage than expected. While reasons behind this relatively surprising number need further investigation, it is worth noting that the sample is small and localized.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study establishes a step towards understanding both male and female homosociality. Despite its limited participant tool, the small localized sample creates an in-depth and cohesive look under a college setting, recognizing specific characteristics and linguistic features in context to better understand homosocial friendship dynamics. Furthermore, the four particular areas reflect the fundamental concepts between vertical and horizontal homosociality. For example, females are more likely to form friendships horizontally and use lexicon reflective of emotional closeness compared to males, providing specific observations worthy of analyzing between the two genders.

The study needs further investigations to capture the essence of homosociality between sexes. One future direction is to acquire larger sample sizes for a more holistic understanding of homosocial friendship dynamics. It includes surveying a much bigger and more inclusive target population. Expanding the survey pool to more college participants can help further research the underlying patterns that a smaller sample size may fail to show. A more diverse target population should also be considered, such as surveying varying ages and occupations across different generations of gender. Different age groups may prompt different responses to incorrect perceptions of sexuality, taking into consideration the context under which they grew up and the societal ideals toward homosexuality at that time. Both of these paths of research are worth exploring for the future, whether to dig deep into the college setting or to grow to a broader population.

Another future direction of this research is to expand the sexuality of the pool of participants. This research aimed to study heterosexual male and female participants within homosocial friend groups. However, studying homosexual males versus heterosexual males or homosexual females versus heterosexual females can lead to new directions. When participants are all of one sexuality within a homosocial friend group, how would their responses differ compared to when participants are of varying sexualities? Would those in friend groups with varying sexualities be comparatively more accepting and inclusive? Would more lexicon related to homosexuality be used without fear? These questions open up new paths of research, further honing down on the topic of sexuality in terms of homosociality and sex. Whether it’s the “bros” or the “babes,” male and female homosocial friendship dynamics are densely packed. While the overall homosocial friendship dynamics for males and females in this study reveal no significant difference, their relative scores and specific responses establish the distinction between how males and females perceive, build and maintain intimacy linguistically.

References

BIRD, S. R. (1996). Welcome to the Men’s Club: Homosociality and the Maintenance of Hegemonic Masculinity. Gender & Society, 10(2), 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124396010002002

Hammarén, N., & Johansson, T. (2014). Homosociality: In Between Power and Intimacy. SAGE Open, 4(1), 215824401351805–. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013518057

Kulick, D. (2000). GAY AND LESBIAN LANGUAGE. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29(1), 243–285. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.243

Rose, S. M. (1985). Same- and cross-sex friendships and the psychology of homosociality. Sex Roles, 12(1-2), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288037

Sanders, K. (2015). Mean girls, homosociality and football: an education on social and power dynamics between girls and women. Gender and Education, 27(7), 887–908. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2015.1096921