Kara Chu, Iffet Dogan, Jay Iyengar, and Alisara Koomthong

The following research seeks to observe linguistic variability in the way Asian immigrant parents speak to their Asian American sons compared to their daughters. Participants for the study include two female participants and one male participant who recorded phone calls with their parents sharing both good news and bad news. The phone calls were analyzed for linguistic variability through word choice and intonation use by the participants’ parents. In addition to data collection, scenes from television shows that represent Asian American family dynamics were analyzed to find possible linguistic variability in the way parents spoke to their daughters in comparison to their sons. This research aimed to uncover the use of gendered language within the cultural norms of Asian American parent-child relationships. More positive language and lower tonal variability were found with the parents of the boy, while more practical language and higher tonal variability were generally found with the parents of the girls.

Introduction

Children are known to absorb cultural linguistic expectations and gender norms imposed on them from interactions with their parents and caregivers. We are seeking to explore the common gender differences that children of Asian immigrant parents experience when speaking to their parents. By analyzing the parents’ supportive phrases, negative phrases, tone, and pitch in varying situations, we will look at the difference in language use towards sons versus daughters. Research has shown that mothers talk more and use more supportive language with their daughters than with their sons (Leaper et al., 1998). We hypothesize that our findings will align with existing gender research, and we aim to go one step further by viewing the data with a cultural lens to examine the intersection between how gender and culture may affect the children’s self identity.

Background

Asian families hail from a wide variety of cultures on the Asian continent, many of which are rooted in patriarchy. These customs have resulted in internalized misogyny within many Asian American families, leading to a distinct difference in the way they treat sons versus daughters. Fong (1997) addresses how Asian American women are in “the midst of conflicting values, identity crises, consciousness raising” all while developing their sense of womanhood (92). Asian Americans are subject to harmful stereotypes, which often include the rhetoric that Asian American women are submissive and incompetent compared to men. This is why we find it valuable to study if there are any linguistic markers that would help us understand how this difference in expectations is communicated to children. We are seeking to observe not only the linguistic variation in the way Asian women are spoken to in comparison to men, but also to make connections about whether that inflicts an altered self-image for Asian American women.

Methods

For our methodology, we wanted to recruit men and women from Asian-American family households that speak English with their parents. Due to our specific demographic, we could only find three Asian-American participants in their 20s: two women and one man. Initially, we had one more male participant, but he decided to drop out at the last minute. Each participant gave out their versions of good news and bad news (i.e. aced an exam, dropped out of school) that aligned with their lives, which enabled them to steer the conversation freely and have our results be as natural as possible. After obtaining all the participants’ and their parents’ consent to be recorded, we collected the recordings of their conversations of them delivering their news and getting their parents’ reactions. One of our female participants presented fake good and bad news while the male and the second female participants’ news were true. Only our male participant had both of his parents in the conversation while the rest interacted with either their mother or their father.

In order to support our data, we examined scenes from television shows relevant to our experiment: Never Have I Ever and Kim’s Convenience. It provided us insight into how media portrays the relationship between parents and their children in an Asian-Western household. In Never Have I Ever, the scene we chose was when the mother assumed the worst in Devi (her daughter) after Devi’s classmate said “Well you know Devi. She is a real firecracker.” In Kim’s Convenience, we used two scenes: the first was an interaction between the daughter and her parents and the second was between the mother and the son. Both were delivering the bad news to the parents and we were able to find a significant difference in how they were treated.

Results

1. Word Choice

We began by analyzing word choices used by the parents in response to good and bad news. All words have tones, and individuals make choices to use certain words/tones to convey more meaning than literal definition (Bakhtin, 1982). When certain tones are repeated in conversation with a specific individual it can begin to have an effect on their mood and lead to longer-term consequences. A study by Richter et al. (2010) provides more support for this by analyzing MRI scans of individuals when certain tone-words are spoken to them, noting that brains react differently to words with different moods and the subjects’ emotions can be changed by language itself (Richter et al., 2010). When parents apply this approach to their children, consistent usage of certain language can have long-lasting effects on development.

Our first subject’s (a girl) parent was less congratulatory than the other parents and seemed to place high expectations on his child:

Figure 1. [8:58-9:10]

06 KID: I like kept messing up my interview questions and they were like asking me things and just the structure was really weird so like I think I did really bad

07 PAR: Oh no (.) You always do so well

He uses comparative statements in response to the bad news: “you always do so well.” He also focuses on areas where the student’s grades may be falling rather than offering comfort. Even in response to good news, he begins with a question, as if doubting the ability of her child to succeed:

Figure 2. [6:53-7:07]

01 KID: You know the um homework I was doing earlier today? I got a hundred percent(.) My grade came back already

02 PAR: You wait you got a hundred percent what?

03 KID: On the homework I was just doing

04 PAR: Awesome;

05 KID: Yeah

The congratulatory “awesome” that the parent offers is the only positive word choice in the entire conversation. Even so, our analysis of tone points towards the positivity of such a statement being muffled at best. At other points in our first subject’s conversation, he focuses on how much his child’s success will be affected, rather than mollifying her emotions. Regardless, it appears he still has the best interests of his child at heart.

Our second subject’s (a girl) parent took a similar tone. Instead of positive language use, when speaking to her child, she stays within the bounds of advice and hedging:

Figure 3. [2:41-2:56]

01 KID: It’s just really embarrassing

02 (2.1)

03 PAR: Then you talk to your advisor ask that fo:r advice that what you to do some things it is out of your control you can’t do anything (.) don’t stress for that

She is more concerned with her child’s actions and success than her well-being, and uses direct language (the ‘command’ to talk to her advisor) to ensure that happens. In response to good news, she uses the words “not bad”:

Figure 4. [4:48-5:01]

04 PAR: How-how many hou:rs does he require you to help [him?]

05 KID: [three] hours a week

06 PAR: OH not bad

07 KID: Yeah (.) yeah

08 PAR: That’s good

And in response to the student’s worries, she offers advice and stresses the idea of working hard. Girl 2’s parent is practical and expects independence from her child, and uses her language to communicate that to her daughter. She continues in the conversation to use neutral or negative language, even in positive reactions, implying through her “negative” reaction to her daughter that what she is doping should not be thought of positively; only that it is expected behavior.

On the other hand, our male subject’s parents do provide some practical advice, but we note a lot more positive language in their interactions. When presented with good news, the boy’s parents’ language and tone are happy, with audible laughter and multiple positive statements:

Figure 5. [0:00 – 0:30]

01 KID: Good news is that I got an A on my environmental econ midterm

02 DAD: Oh [very nice] (1.5) [yeah]

03 MOM: [mmm:::] [congratulations!]

04 MOM&DAD:(inaudible)<<laughing>>

05 MOM: Good job!

06 KID: Thank you.

07 MOM: <<laughing>>

And perhaps even more interesting, when confronted with bad news about his budget, the parents continue to use words like “thank you for letting us know” and place trust in his ability to handle his business, telling him to keep track of his own budget:

Figure 6. [0:42-1:01]

08 KID: ‘Ca-’cause like I feel like–it feels like I’m spending too much but I’m like–I . should probably keep track of my budget better (0.1) [so:] (0.2) we’ll see

09 MOM&DAD: [Oh:]

10 DAD: You stay within your budget?

11 KID: Well–I–I need to be better about that. [So we’ll see]

12 DAD: [Oh okay]

13 DAD: Well, thank you for letting us know about [that]. So, you know,

14 MOM: [yes]

15 DAD: Keep track of your budget(1.2)and how much you spent.

We do not have enough data to tell whether these are truly differences between treatment of girl/boy children or simply differences in parent personality, as we know parent gender in addition to having one parent versus two parents present can affect the conversation. However, there are minute trends in word choice that differentiate the two genders. The boy’s parents are more positive about his accomplishments and more trusting of his faults, while the girls’ parents take a more high-expectation position and are more neutral about their efforts.

2. Intonation

In addition to evaluating word choice, we also put the recordings into a speech analysis software called Praat to analyze pitch and intonation. According to previous research, intonation, which is the change in pitch, is a really important part of communicating a speaker’s emotions and their attitude towards the listener (Wells, 2006). Their pitch will differ depending on what emotion the speaker is conveying.

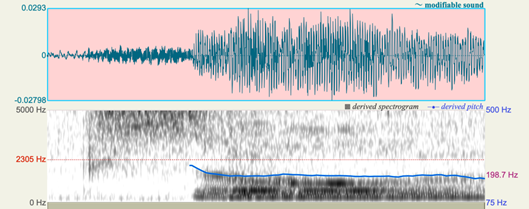

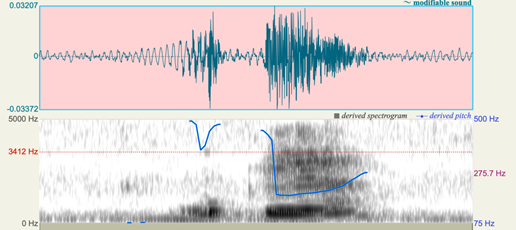

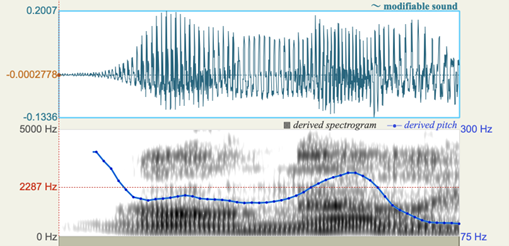

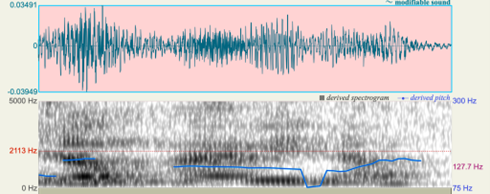

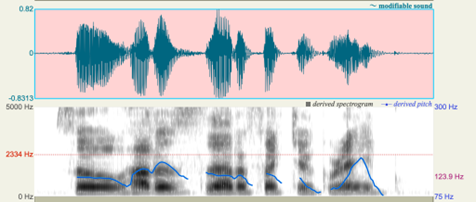

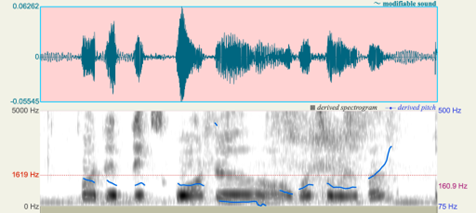

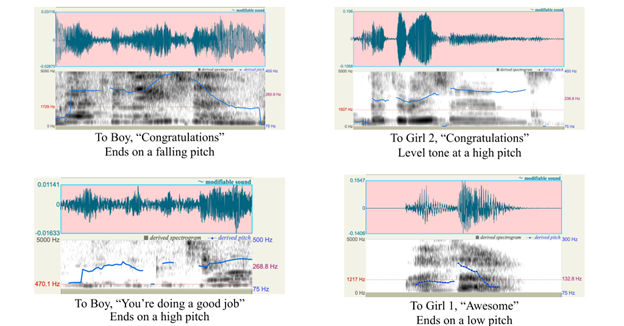

The first thing we looked at was the parents’ initial short one-word response to the child’s piece of bad news. For the boy, it was “Sooo,” and for the girls it was “Oh no” and “Okay?” as seen in Figures 7 – 9. These spectrograms show the strength of certain frequencies as a speaker talks. Their pitch is indicated by the blue line. We used a pitch range of 75 to 300 Hz for male speakers and 75 to 500 Hz for female speakers, as females have a higher speaking pitch. We found pretty consistently that the parents of the girls had higher tonal variability, meaning their pitch changed a lot, while the parents of the boy had low tonal variability. However, we acknowledge that the content of the speech can have an effect on the speaker’s pitch which can make it hard to compare one to one.

All the parents asked their kids a question after hearing the bad news. For the boy, one question his parent asked was “you don’t have enough?” which has a low tonal variation, as seen in Figure 10. He doesn’t increase pitch at the end which you would normally expect from a question, especially a yes or no question.

On the other hand, you can see the parent of Girl 1 varied a lot in intonation in Figure 11 during the question, “So how does that affect your grade?”. Girl 2’s parent’s pitch didn’t change as much throughout the sentence, but a big pitch increase is seen at the end of the yes or no question “If you fail, can you retake the class for the next quarter or whatsoever?” in Figure 12. This expresses itself much more like a question as opposed to the boy’s parent, whose question ends on a level pitch similar to a statement.

This difference in parents’ tonal variation for questions is consistent with the parents’ tonal variation in their one word responses. For responses to bad news, the parents of daughters used more tonal variability than the parents of the son.

However, for the responses to the good news, we couldn’t find a clear difference between the boy and the girls. For both, the parents said congratulations, which for the boy has more variety and ends on a falling tone while for the girl has a level tone at a high pitch. We looked at another congratulatory phrase from the parents, and you can see variety for both the boy and girls. We believe this could mean that parents react to good news similarly regardless of gender pitchwise.

3. Media

Media plays a large role in reflecting the dynamics between Asian American parents and their children. One example of this is Devi from the show Never Have I Ever.

B: well you know Devi (.) she’s a real firecracker.

N: Oh no :: what did she do?

In this particular scene, Devi’s classmate Ben refers to her as a “firecracker” to which her mother, Nalini immediately assumes the worst and jumps to the conclusion that Devi did something wrong. In general with Devi’s character, in the midst of developing into womanhood and growing up, she is constantly given these types of negative reinforcement about her personality traits that are commonly misconstrued as “unladylike”. She is outspoken and expressive and often reprimanded for being that way, as this particular scene represents. Media representations such as the show Never Have I Ever are reflective of these kinds of parent-child relationships and interactions that many Asian American women face in real life.

In Kim’s Convenience, Jung is the oldest and the only son of the family where high expectations were placed on him. He told his mother that he applied for a new position in a car rental company that has higher pay and responsibilities, however, his mother interpreted it negatively.

Jung: Assistant manager, Umma. And it’s a good job. It’s got more pay, benefits, and more responsibility.

Umma: So does doctor or judge or (1.2) website design!

The mother’s response was a clear indication that she was not satisfied with her son’s choice. She wanted him to choose a career that is more reputable, such as a doctor, a judge, or a website designer. It is a portrayal of Asian parents’ ideas of what is best for their children by setting high standards for them to follow.

Janet is the youngest and only daughter of the family. In comparison to Jung, she has fewer responsibilities and lower expectations than him other than to be obedient. In Season 1, Episode 10, Janet’s friend revealed to her parents that she got a job without their approval.

Umma: Janet, you get job?

Gerald: At the car rental store. She starts tomorrow.

Umma: At Handy Car Rental?

Janet: Yeah

Umma:(1.6)*sigh* N(h)o, Janet. You work here. You tell them it’s

mistake. Tell her, Appa

Appa: You know what’s a big mistake? Pork rind. Never sell. Look.

[5:39-5:48]

Janet: I need the job, Umma. How else am I going to earn any actual money?

Umma: We work something out. Right, Appa?

Appa: And what’s the deal with the wine gum? Not wine, not gum.

In this scene, both parents were dismissive of her but in different manners. The mother was trying to reassure her that she did not need a different job because she is already working at their family’s store and was persistent for her daughter to stay. The father, on the other hand, reacted by not responding to her news. Instead, he decided to change the topic as if it did not matter to him. It’s a representation of how parents would have low expectations from their daughter in this scene but try to influence her to be compliant with them. Her individuality can only be accepted if it aligns with their concept of what is best for her.

Conclusion

We found that hedging was used by parents of both boys and girls, but that girls’ parents used it significantly more. The parents of our male subject also spent a lot of time reacting to and understanding his problem, while the girl’s parents tended to offer more vague advice and “close off” subjects as soon as they were done offering their piece on the subject, before moving on to the next subject unless the child brought it up again. For both genders, the parents provided serious advice, but the advice for the boy was more direct when it was given while the girls’ parents provided mostly vaguer advice to their children, often having to do with working harder or being more resolute in the face of challenges. When presented with issues in the students’ lives, the girls’ parents were significantly more negative or neutral in speech, and placed far higher expectations through their word choice when reacting to bad news, while the boy’s parents were hopeful and positive in tone, implying a sense of trust in their child’s ability to fix his issue. Intonation varied less for the boy’s parents than it did for the girls’ parents, and the girls’ parents’ intonation varied the most especially when reacting to bad news.

The data has not supported pre-existing research studies on this topic and our hypothesis that more supportive and positive language would be used with the girls. While we were able to dissect and analyze the data that gave some clear distinctions between sons and daughters, the obstacle of finding participants does not allow us to give a definite conclusion or correlation from our small sample and apply it to the general public. There are several factors as to why we cannot definitively conclude that gender is the sole cause of the linguistic differences. For instance, parents may have more progressive views that are from Western or American culture instead of their heritage and/or not speaking the inherited language with their children. Another contributor includes the level of closeness and comfort. The data would have been stronger if we included various levels of connection between parents and their children to observe any similarities and differences in their language. If we have the opportunity to conduct this experiment again, we would take more time on the recruiting process as that was our main issue. Additionally, we would want both parents present when interacting with our participants so everything is more consistent. Regardless, our study provides an often-forgotten insight to the relationships between Asian American students and their families, and through such understanding, we can only hope to foster more thoughtful and egalitarian approaches to parenting children.

References

Bakhtin, M. M., & Holquist, M. (2000). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. University of Texas Press.

Fong, Lina Y. S. (1997). Asian-American Women: An Understudied Minority. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 24(1), pp. 7.

Leaper, C., Anderson, K. J., & Sanders, P. (1998). Moderators of gender effects on parents’ talk to their children: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 34(1), 3–27.

Wells, J. C. (2006). English Intonation PB and Audio CD: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richter, M., Eck, J., Straube, T., Miltner, W. H. R., & Weiss, T. (2010). Do words hurt? brain activation during the processing of pain-related words. Pain, 148(2), 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.009