Julia Offerman, Isabelle Sandback, Samantha Morgan, and Niki Agarwal

Societal viewpoints regarding sports can be partially attributed to gender bias in sports commentating and interviews. This is true even for tennis, which has become very gender-inclusive in terms of media coverage, as well as respect for female athletes. Still, many studies have found biases in language used for male and female tennis players—but have not examined interviews or interview questions. In this study, we analyzed six post-game interviews of mixed doubles tennis players to ascertain if there was a difference in questions directed to female and male tennis players. We observed the proportion of emotional and practical questions directed to each, as well as the proportion of questions regarding the interviewee themself, their partner, or teamwork for each player. We found that the women were asked significantly more emotional questions than their male counterparts, but that both were asked relatively similar percentages of interviewee-partner-teamwork questions. This study has important implications for language, respect, and gender-inclusivity surrounding tennis and women’s sports, as well as interview protocol between men and women interviewees in other fields. These metrics analyzed could be used in these other cases, and ideally, the differences should be mitigated in order to promote equality in interviews.

Background

Although media coverage of tennis has been more gender-inclusive than other sports, biases are still present in the language used by interviewers when interacting with male versus female tennis players. In our study, we analyzed the post-match interviews of mixed-doubles teams, which consisted of one female player and one male player, to see if word choice and question type display any gendered bias. This allowed us to test the hypothesis that gender-based bias found in broadcasting also extends to in-person interviews with the athletes.

Gendered language in tennis has served as the subject of several studies. Though the definition of gender may be fluid depending on context and background, tennis itself has established a gender line between male and female that we used as our baseline. Previous studies, such as Messner and Jensen (1993), have compared the broadcasts of men’s and women’s tennis matches because they are usually held at the same venue and given equal amounts of coverage.

Articles reporting on the 2015 Australian Open were analyzed for “gender-specific descriptors” in a 2016 study conducted by Adrian Yip (2016). It was found that “stereotypical beliefs about females were largely reinforced in mediated gender representations,” and specifically focused on the disproportional discussion of women’s appearance, mental-weakness, and other stereotypical female traits (Yip, 2016). The 2015 Australian Open media coverage was additionally analyzed by the International Review for the Sociology of Sport, and strong gendered differences in how announcers “created spectacle” and described athletes during the live matches were found (Quayle et al., 2019). Commentators were again analyzed during the 2018 US Open and found that they reported emotionality more frequently with female athletes (Gerbasi, 2019).

Despite the focus on bias in sports media coverage, no studies have looked at how gender bias shows up in press conferences and interviews. Interactions with the players deserve their own focus since reporters are not describing the athletes or offering their own commentary, which therefore makes it more difficult to identify examples of stereotypes or biased language.

Overall, we expect that female athletes will be asked more emotional-coded questions and males will be asked more practical-coded questions. In addition, we hypothesize that women will be asked more questions about their partner than men will be asked about their partner, and that women will be asked more questions about teamwork in general. If we see these differences, we can determine that there may be bias in the question choice when directed towards female and male athletes.

Methods

For our study, we looked at post-match interviews from Grand Slam tennis tournaments and decided to focus exclusively on mixed-doubles teams. Since a mixed-doubles pair includes one female and one male athlete who are both being interviewed about the same match, gender is isolated as a difference between the players; therefore, the differences in the questions posed to each athlete could be indicative of gender biases. We chose to analyze 6 formal interviews of players that were successful (had each won major tournaments before both in individual and doubles events) and well-known within the tennis world. The interviews totaled 71 minutes for analysis. Additionally, we chose to disregard the gender of the interviewers because the questions seemed to be highly scripted and therefore not indicative of the interviewers’ personal biases. After an initial scan, we conducted two waves of analysis: one that marked the subject of the question (i.e. emotional versus practical) and one that marked the referent of the question.

For the first part, we defined “emotional questions” as questions that either are meant to elicit an emotional reaction or ask about the player’s feelings. We looked for keywords or question topics that indicate emotions, specifically focusing on—but not limited to—the following list of keywords and concepts: therapy, emotional wellbeing, “feel,” personal life, emotional reaction to the results of the match, “happy” instead of “satisfied,” support. We used this framework in order to tally and average the number of emotional questions directed towards the female and male athletes.

An example of an emotional question is the following, posed to Serena Williams at the 2019 Wimbledon Tournament:

(1) “You said you had gone to see a therapist after the-dealing with the uh US Open incident, can you just talk about that process-what it did for you and how maybe it has affected you going forward?” – Question to Serena Williams in the Second Round Mixed Doubles Press Conference Wimbledon 2019 (0:16)

This targets both personal life and therapy, making the question emotional. Other times, the lexical choices indicated gender biases—competition related for the male player and emotional/psychological interaction for the female—such as in the following questions:

(2) “Were you surprised at how well you came together, you really seemed to have excellent chemistry this week?” – Question to Martina Hingis in the Mixed Doubles Finals Press Conference Australian Open 2015 (5:55)

(3) “How is the mixed doubles helping mentally and physically your, you know, your ambition to get back to singles?” – Question to Andy Murray in the Mixed Doubles Second Round Press Conference Wimbledon 2019 (6:38)

(4) “How did it feel to hit so many return winners against Martin?” – Question to Serena in the Second Round Mixed Doubles Press Conference Wimbledon 2019 (9:17)

In the second round of analysis, we tracked each question’s referent by sorting them into three possible categories: questions referring to the interviewee, questions referring to the interviewee’s partner, and questions referring to teamwork. We marked questions as referring to the interviewee when they asked about the player’s personal life, mental health, individual match play, opinions on larger news stories, etc., such as in the following question:

(5) “Andy, on TV you said that uh once Wimbledon finishes, hopefully on Sunday, you’re gonna practice a bit more singles? Does that mean you’ve made your decision about if you’ll go to the US Open or you will try the US swing as a singles player?” – Question to Andy Murray in the Second Round Mixed Doubles Press Conference Wimbledon 2019 (0:48)

Questions were marked as referring to the interviewee’s partner when players were asked about the other’s personality, habits, or style of play, such as in this example:

(6) “What is it about playing with Jamie that is so good for you?” – Question to Bethany Mattek-Sands in the Mixed Doubles Final Post-Match Interview US Open 2019 (2:29)

Finally, questions were marked as referring to teamwork when players were specifically asked about their partnership or future plans to play together. For instance:

(7) “You said on court that you only sort of teamed up again in the last couple weeks, was there ever a chance that you weren’t going to play together?” – Question to Neal Skupski in the Mixed Doubles Final Press Conference Wimbledon 2022 (11:42)

We conducted a paired t-test for each set of averages in order to determine the statistical significance of our results.

Results

On average, male tennis players were asked 58.33% of questions and females 41.67%, which was not significantly different (p-value=0.16).

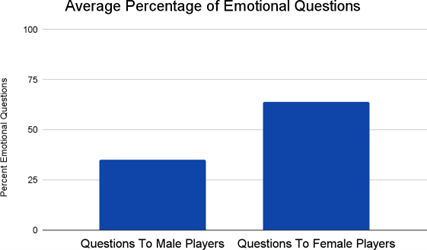

Of the questions asked to the male partner, 35.83% were emotional-based and 64.33% to the female partner. This gives a two-tailed p-value of 0.006, which is very significant. Out of the total emotional questions, the female partner was asked 64.5% of the questions on average, with a p-value of 0.04, also significant.

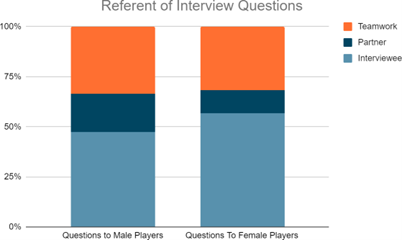

Of the questions asked to the male, 51.4% referred to themselves, 17.7% referred to their partner, and 30.9% referred to teamwork. Of the questions asked to the female, 54.6% referred to themselves, 14.8% referred to their partner, and 30.6% referred to teamwork. The p-value between these two groups is over 0.9, indicating that there is no significant difference between the questions for male and female tennis players regarding if the question is about themselves, their partner, or teamwork.

Discussion

Overall, the study indicated that there were some significant differences in the questions directed at male and female tennis players, but certain aspects were more likely to be gender specific than others. Based on the data, we can accept our hypothesis that female tennis players tend to be asked more emotion-based questions than male tennis players on average. We cannot, however, accept our hypothesis that female tennis players are asked more questions about their partner than male tennis players are, as the proportions are similar. This could indicate that emotional versus practical questions could be a metric for examining gender bias in sports interviews, but interviewee-centered versus partner-centered versus teamwork-centered may not be—at least, for mixed doubles tennis.

This has several implications not only for current perceptions of men’s and women’s sports, but for future actions that should be taken in order to mitigate gender bias in sports interviews. Based on the current understanding, interviewers direct more emotional questions towards female tennis players, which can undermine their competitive and athletic ability. If equal respect is going to be given to male and female athletes, the proportion of emotional and practical questions should be comparable for both genders—and this must be done deliberately. Though emotional aspects can be relevant in an interview or discussion with athletes, the priority should likely be the competitive aspects to establish any athlete’s prowess as paramount. “Gender Inequality in Sports: Women Face a Double Bind” from the publication The Hilltop Monitor, talks about a running hashtag back in 2015 called “#CoverTheAthlete.” This hashtag was created in order for people to highlight how male and female athletes were interviewed online and in the news, or, more importantly, how females were asked questions not related to their skill or game, but ones about personal life, looks, emotions, and how they felt about the male-side of sports. The author’s hypothesis was to see if there was a link between these interview differences and female athletes’ pay. Women are paid incredibly lower versions of their male-counterparts’ salaries. “The Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) had a 2018 salary cap of $110,000 while the National Basketball Association (NBA) minimum salary was $582,186” (Porth 2019). The blog argues that gendered language and lower pay go hand in hand; if female athletes are going to be interviewed like their games do not matter, then their games will matter less to people, resulting in less revenue. Does the request “can you give us a twirl” sound like what an interviewer would ask to a serious, skilled player? It might be why women’s sports are seen as less serious than men’s.

Furthermore, tennis is a sport in which female athletes are seen as relatively equivalent to their male counterparts when compared to athletes in other sports. This suggests that the disparity could be even greater in other sports, underscoring a need for studies such as these to explore the way gender bias presents itself. The emotional and practical question metric could be applicable in these cases as well, and the necessity for similarity in questions directed to athletes of different genders in order to promote equal respect is key. Further differences in interview questions between men and women may be present in other industries and fields, which is another area for future development.

In order to truly determine if gender biases were present in these interviews, we specifically needed to limit the scope of this study to focus on quantifiable and qualifiable differences in the questions asked to male and female athletes. However, each athlete has multiple other aspects of their identities that could affect how they are perceived, such as race and age. There are intersections between said identities that may play an additional role in the choice of questions directed to them. Broadening the extent of this study could help account for some of these intersections. In addition, a longer study with more interviews would be ideal in order to further solidify the relationships noted.

There are efforts that can be made to help reduce the biases held regarding women’s sports in general, which can be considered a possible cause of the difference in questions posed in interviews. The International Women’s Day campaign offers a few ways that individuals can combat biases in women’s sports. Encouraging young women and girls and supporting them in sports can help instill equitable perceptions at a young age. Additionally, closing the gender gap in sports salaries will improve the legitimacy of women in the field. One of the easiest ways anybody can make a difference is simply supporting professional sports in any way, from attending a game to buying merchandise (“Support female athletes”). Supporting women and being aware of the stereotypes reflected in their sports interviews will contribute to the effort in improving gender inequities. This study, among many others, has revealed evidence of gender biases and awareness of this prejudice can allow for progress towards eliminating it.

References

AK. (2016, June 4). Martina Hingis and Leander Paes seal career grand slams at French Open. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8Fh-fF8Zek

Australian Open TV. (2015, February 1). Martina Hingis and Leander Paes press conference—Australian Open 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAPoYiZHzeU

Cooky, & Messner, M. A. (2018). No slam dunk: gender, sport and the unevenness of social change / Cheryl Cooky and Michael A. Messner. Rutgers University Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/2124054

Gerbasi, A. (2019). Game, Set, and Match: A Content Analysis on the Commentating of Tennis Broadcasters for the 2018 US Open Championship Weekend. [Master’s thesis, East Tennessee State University]. ProQuest, https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3575

Messner, Duncan, M. C., & Jensen, K. (1993). Separating the Men from the Girls: The Gendered Language of Televised Sports. Gender & Society, 7(1), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124393007001007

Porth, M. C. (2019). Gender Inequality in Sports: Women face a double bind – The Hilltop Monitor. Retrieved December 8, 2022, from https://hilltopmonitor.jewell.edu/gender-inequality-in-sports-the-double-bind-women-face/

Quayle, M., Wurm, A., Barnes, H., Barr, T., Beal, E., Fallon, M., Flynn, R., McGrath, D., McKenna, R., Mernagh, D., Pilch, M., Ryan, E., Wall, P., Walsh, S., & Wei, R. (2019). Stereotyping by omission and commission: Creating distinctive gendered spectacles in the televised coverage of the 2015 Australian Open men’s and women’s tennis singles semi-finals and finals. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217701889

Support female athletes worldwide and help #breakthebias in women’s Sport. International Women’s Day. Retrieved December 7, 2022, from https://www.internationalwomensday.com/Missions/17255/Support-female-athletes-worldwide-and-help-BreakTheBias-in-women-s-sport

US Open Tennis Championships. (2019, September 7). Mixed Doubles Final—Ceremony and Post Game Interview | US Open 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMDNRmO1cyY

Wimbledon. (2019a, July 9). Andy Murray & Serena Williams Second Round Mixed Doubles Press Conference Wimbledon 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cqckd0HxyWY

Wimbledon. (2019b, July 10). Andy Murray & Serena Williams Third Round Press Conference Wimbledon 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o_AD9GhiFNA

Wimbledon. (2022, July 8). Neal Skupski and Desirae Krawczyk Final Press Conference | Wimbledon 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DamI3-8RWjU

Yip, A. (2018). Deuce or advantage? Examining gender bias in online coverage of professional tennis. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 53(5), 517–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216671020