Catherine Le

The impact that teachers have is invaluable due to their power to shape futures and develop minds, and the Undergraduate Learning Assistants (LAs) at UCLA are no different. They undergo extensive training to teach their peers alongside graduate student TAs, and with so much weight on their shoulders, they must be well-equipped to treat all students equitably, right?

After analyzing video footage from LA/student interactions in lower-division STEM courses, educational strategies utilized by instructors like wait time, interruptions, and praise were evaluated to recognize the presence and magnitude of a gender and power asymmetry in classrooms. The study revealed that there is a significant difference between how the genders interact, and the discovery of these results show that instructors possess the ability to not only expose their students to, but unfortunately also normalize the social realities of gendered behavior. Therefore, recognizing the existence of a gender gap and unequal power dynamic between instructor and student could help future educators make the program and its goals to encourage interest and retention in STEM more achievable.

Introduction

The Learning Assistant Program at UCLA was established as part of an initiative to facilitate active and collaborative learning in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) courses by teaching undergraduates how to instruct future cohorts of various lower-division courses. The program significantly and positively impacted students: on exam questions requiring higher-order cognitive skills, students with LA exposure performed significantly higher than students without LAs in their classrooms, and students of minority groups especially benefited from LA support (Sellami et al., 2017). While the program is comprehensive in many aspects and does a great job of helping student pass on the gift of teaching and education onto their peers, the topic of educational gender bias has been neglected. Therefore, gendered linguistic choices may reveal if the academic playing field is truly level.

Research has indicated that male and female teachers teach differently, so this study explored specifically how both genders exercise wait time, interruptions, and praise differently with their male and female students (Lacey et al., 1998). Wait times (the time between asking a question and speaking again), connect to West and Zimmerman’s claims about silences and interruptions. According to them, men utilize interruptions to dominate women in conversation and limit silences in an effort to gain conversational power; my study expands specifically on how males in classrooms exert dominance over females, especially male instructors (1983). Also, teachers’ interruptions and shorter wait-times are associated with obstruction of student participation and overall learning effectiveness (Yataganbaba & Yildirim, 2016). Yet another vital tool employed by teachers to motivate students that is influenced by gender is praise, with Wilkinson and Marrett finding that female educators are more complimentary (1985, p.122). Equally important is how this praise is earned; praise based on effort (process praise) motivates students more effectively than praise based on accuracy (person phrase) (Corpus & Lepper, 2007). The majority of this research was performed in primary school classrooms, but my research extends this literature to college students. By exploring these aspects as utilized by undergraduate instructors, we may be able to reveal underlying issues and biases in the educational system, which would require immediate attention and rectification.

Methods

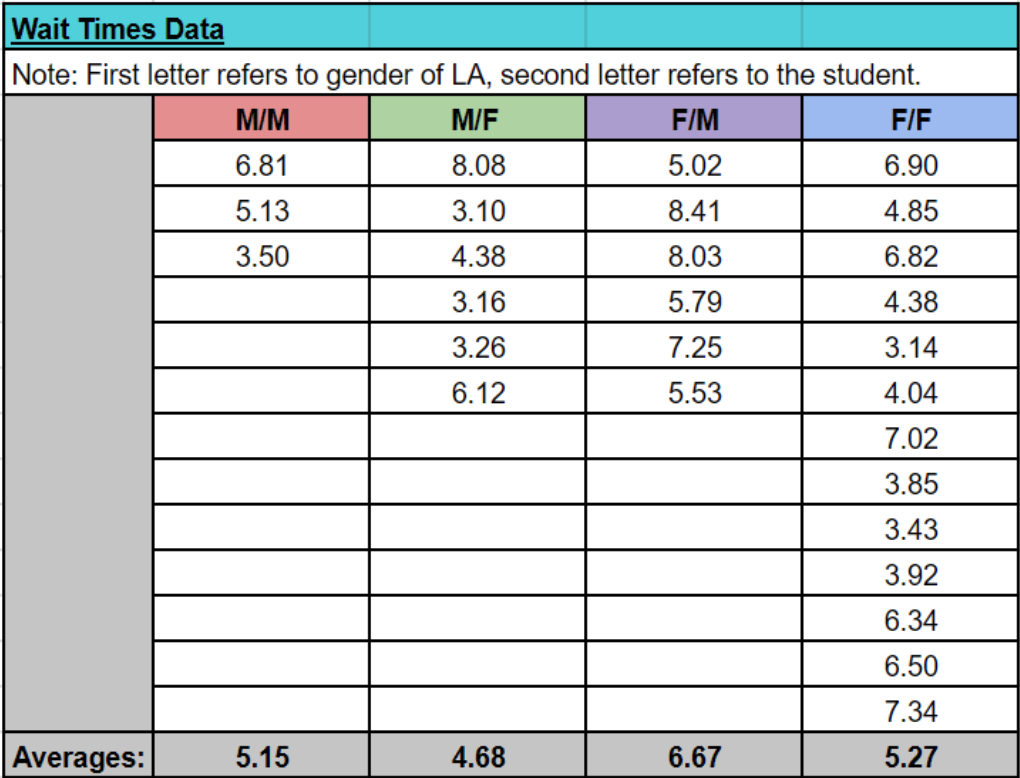

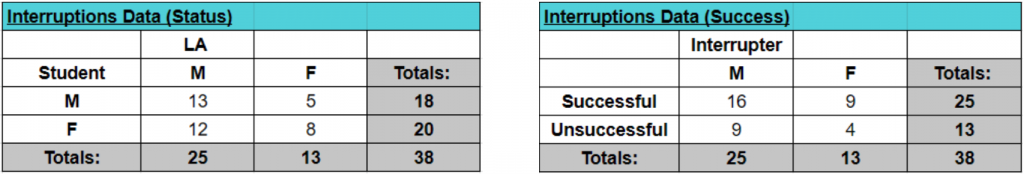

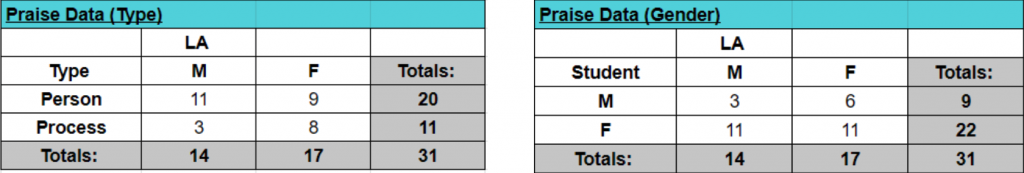

As a part of the program, LAs record footage of them interacting with students during class to track their own progress. Nine LAs volunteered 67 minutes of male LA-led interactions and 71 minutes of female LA-led conversations, and these conversations were categorized as follows: Male LA-Male Student (M/M), Male LA-Female Student (M/F), Female LA-Male Student (F/M), and Female LA-Female Student (F/F). Three aspects were then recorded and analyzed in this study─ (1) Wait times, (2) Interruptions, and (3) Praise.

First, wait times were defined as silences exceeding three seconds between an LA asking a question and either the student answering it or the LA following up. Next, interruptions were outlined as instances where the original speaker was disrupted by another individual; they were classified as successful if the interrupter then took a turn in the conversation to finish their thought, or as unsuccessful if the interrupted subsequently regained control of the conversation. Lastly, praise was characterized as any verbal encouragement from the LA to the student. Person praise referred to comments that complimented the student’s abilities or the accuracy of their answers (e.g., “You got the right answer!”) and process praise emphasized the student’s efforts (e.g., “I liked your logic.”) All data was recorded and analyzed by computing averages (for wait time) and tallies of instances (for interruptions and praise).

Results and Analysis

The results of the study suggest evidence of a gender bias perpetuated by Learning Assistants across all three different aspects I examined. The magnitude of difference between genders did vary, but most of the hypotheses discussed were confirmed to some degree.

1. Wait Time

Generally, male LAs used wait time much less than female LAs and for shorter periods; the lowest wait time averages and instances were observed out of four M/M Student interactions. However, the highest average wait time was found with F/M interactions. A strikingly large difference between LAs was found in F/F conversations, with a total of 13 instances of wait time versus 3 occurrences in M/M interactions. Table 1 summarizes the length and number of wait time incidences in the four different categories previously mentioned.

In most conversations, male students filled silences with filler words and phrases like “Well…” and “Hmm” while female students would wait until they had formulated a cohesive reply. Males’ tendency to reply quickly is consistent with demonstrating that they have mastered the knowledge required to answer the question as an effort to preserve positive face. Brown and Levinson defined the concept as a component of an individual’s public self-image that requires approval from others to establish self-esteem, and studentsIn most conversations, male students filled silences with filler words and phrases like “Well…” and “Hmm” while female students would wait until they had formulated a cohesive reply. Males’ tendency to reply quickly is consistent with demonstrating that they have mastered the knowledge required to answer the question as an effort to preserve positive face. Brown and Levinson defined the concept as a component of an individual’s public self-image that requires approval from others to establish self-esteem, and students’ positive faces become threatened if they fail to adequately impress the LA and their peers (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2013, p.122). On average, female LAs created more wait time than male LAs, but gave male students a significantly longer time to think than females. This discrepancy suggests male students do not need to save face with female instructors as much as with male LAs due to a gender asymmetry, or that female LAs boost males’ self-esteem by unconsciously subjugating themselves and allowing men to dominate through language usage. This suggests male students unconsciously allow themselves to take more time because their intelligence and self-confidence cannot be undermined by a female, even if she is in “power” due to her knowledge and status as an LA.

2. Interruptions

Men also interrupt more, with male LAs being the worst offenders at twice the rate of female LAs (Table 2). This can be attributed to the fact that male LAs are ultimately dominant through the combination of their gender and teaching role; their more frequent interruptions are a show of power and dominance in order to gain conversational control. Female LAs interrupt the least due to their hesitance to threaten their students’ positive faces, since interrupting can be seen as a challenge to the thoughts of the original speaker. Conversely, female students forgo politeness to assert that they are just as knowledgeable as their peers, and interrupt frequently to avoid being seen as less confident or competent if they lose control of the discussion.

Both genders are fairly equal in the success of interruptions (Table 3); this is most likely due to the fact that if the interrupted individual thinks the interjection is valid, they will let the interrupter finish their thought. In conclusion, male LAs use their power to dominate all students, but female students will combat that by fighting to control the discussion as well.

3. Praise

When analyzing praise from LAs, evidence of a gender asymmetry was less significant. Males offered slightly less praise than females but complimented other males only 21% of the time (Table 4). In contrast, the highest amount of praise seen was in F/F interactions. The hesitance for male LAs to flatter other males is suggestive of traditional ideals of heterosexual masculinity; acting too complimentary to another male may be misinterpreted as non-professional or could be potentially humiliating. However, females are not subjected to the same risk of being perceived as homosexual, and in a society that frequently preaches for women to stop being “pit against” other women, the data suggests that women are doing exactly that.

Additionally, as seen in Table 5, both genders overwhelmingly focused on person praise, but women used person and process praise more evenly. This aligns with previous research that claimed that women are more complimentary, but the few occurrences of male LAs using process praise can originate from the fact that men use language more abstractly than women; men tend to speak about the “bigger picture” while women utilize specific language (Joshi et al., 2020). Prior research also found that power differences play a part as well, since an individual in a dominant role was more likely to speak abstractly. This suggests that power and gender are intimately connected in ways that cannot be distinctly separated with current research, but future studies should endeavor to delineate how exactly all these mechanisms intertwine.

Conclusion

This study found several indications that gender and power asymmetries exist in the academic field, specifically between teachers and students in STEM courses. Obviously, it would be difficult to believe that LAs intentionally set out to treat their students differently according to their gender, but the fact is that despite best intentions, the imbalance still exists. Unfortunately, research proves that these disparities may have long term effects on the success of students; through analyzing strategies such as wait time, interruptions and praise, male teachers assert power over students more overtly than female instructors. They allow students less time to think, interrupt more often, and praise less often and more vaguely. Still, they are judged to be just as effective as their female counterparts, despite identical performance, personality, and appearance (Mitchell & Martin, 2018). This points to a looming issue within the academic community: if these differences are not being recognized in the first place, how will their effects be addressed?

However, this study was limited: a small sample size of nine LAs was examined due to the voluntary aspect of data collection, and while the recordings were intended to be as representative as possible, some students or LAs may have acted differently in the moment. Future directions for research that could expand upon the current investigation could include: analyzing non-STEM courses to explore whether stereotypes of certain genders excelling in particular subjects may play a role; considering alternative characteristics such as sexual orientation, cultural background, or experience level as an LA to isolate the effects of gender; and exploring if the same trends exist with Graduate Teaching Assistants.

This paper is by no means a conclusive or exhaustive analysis, but it does provide enough evidence to suggest that the LA Program may benefit from expanding its curriculum to expose LAs to the potential of unconscious gender bias in order to ensure a more equitable academic experience for all. This recommendation is further substantiated by this TED Talk by Elizabeth Wolfson, founder of the first all-female school in Denver, discussing the implications of a gender-based education and how it can alter students’ futures. The STEM field is currently one of the largest and fastest-growing industries, but women still only make up 35.5% of the population earning bachelor’s degrees in STEM (Catalyst, 2019). However, while women are attempting to close the gender gap by increasing these numbers, will they ever succeed? Small changes can start in classrooms, and it is up to all of us to guarantee no one gets left behind.

References

Catalyst. (2019, June 14). Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM): Quick Take. https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-in-science-technology-engineering-and-mathematics-stem/

Corpus, J. H., & Lepper, M. R. (2007). The effects of person versus performance praise on children’s motivation: Gender and age as moderating factors. Educational Psychology, 27(4), 487–508. doi: 10.1080/01443410601159852

Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2013). Language and gender. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Joshi, P. D., Wakslak, C. J., Appel, G., & Huang, L. (2020). Gender differences in communicative abstraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(3), 417–435. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000177

Lacey, C. H., Saleh, A., & Gorman, R. (1998). Teaching nine to five: A study of the teaching styles of male and female professors.

Mitchell, K. M. W., & Martin, J. (2018). Gender Bias in Student Evaluations. PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(03), 648–652. doi: 10.1017/s104909651800001x

Sellami, N., Shaked, S., Laski, F. A., Eagan, K. M., & Sanders, E. R. (2017). Implementation of a learning assistant program improves student performance on higher-order assessments. CBE life sciences education, 16(4), ar62. doi:10.1187/cbe.16-12-0341

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1983). Small insults: A study of interruptions in cross-sex conversations between unacquainted persons. In B. Thorne, C. Kramarae, & N. Henley (Eds.), Language, gender and society (pp. 102-117). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Wilkinson, L. C., & Marrett, C. B. (1985). Gender influences in classroom interaction. Orlando: Academic Press.

Yataganbaba, E., & Yildirim, R. (2016). Teacher interruptions and limited wait time in EFL young learner classrooms. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 232, 689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.094