Maddy Doane

Within discourse, the observation of male implicit bias is prevalent and is often caused by words that reflect and refer to generic masculine associations. The question at hand is, does the adoption of gender-inclusive language reduce male bias and therefore, increase women’s involvement in mental associations? In two experiments, I analyze interactions between groups of people either involving gender-neutral words, or not. Afterwards, all people are asked to take an implicit bias test to see if the gender-inclusive language has an effect, if any. The participants are comprised of men and women attending UCLA, all of which are comfortable conversing with each other. In observing conversation, the use of gender-inclusive words reduces the amount of automatic male associations in the subsequent implicit bias test. Thus, explaining the importance of avoiding gender-fair words as well as including gender-inclusive language in everyday conversation. The goal of this study is to inform and educate participants and readers about the effects of adopting gender-inclusive language into common vocabulary.

Introduction and Background

Often, common vocabulary is marked for one specific gender but is continually used as the default word, allowing for gendered language to exist. The gradual shift to include gender-neutral words involves altering words like “fireman” to a more inclusive term, “firefighter”. However, because the word “fireman” originated to specifically describe men that put out fires for a living, and has been in constant circulation since, it is typical to use the gendered word regularly, without even realizing it. Another side effect relies on the implicit associations that brains make when hearing the word “firefighter”, a traditionally male occupation. Although the gender-inclusive word is being used, because of its institution, it is common for it to directly index a male firefighter.

Within this research experiment, the focus is surrounded upon whether shifting to gender-inclusive language reduces implicit associations and removes mental assumptions. In doing so, two experimental groups were composed of multiple groups of UCLA students and their responses and reactions to gender neutral language were recorded. Because the participants share a common concern for gender equality, as do most people, they will learn how to promote gender equality better as they interact regularly.

Through the introduction of gender inclusive language in conversation, understanding the impact of making illogical, implicit associations is revealed and correction of language is made. Demonstrated through implicit bias tests, the phenomenon of those who understood their gendered mistake showed less automatic association towards a specific gender regarding professions was created. Thus, due to the prior exchange, adopting gender neutral language into one’s vocabulary helped intentionally shape others’ implicit associations.

Methods

Multiple groups of UCLA students were randomly sampled from the specific population of the track and field team. They were given the task of formulating a story about the images placed in front of them. The set of images included: a house on fire, a person on the phone, a fire truck, a firefighter with a hose, a firefighter carrying a person to safety, an EMT using a defibrillator, and a person thanking a firefighter. The first set of groups (3) will be asked to formulate a story about the sequence of images and then asked to complete an implicit bias test centered around gendered professions. The purpose of the implicit test is to evaluate attitudes or beliefs that are not normally exposed or reported willingly. For this experiment, participants will be tested on the speed and accuracy of their associations when pairing words like children and business with either men or women, as directed.

Within the next set of groups (3), participants were asked to formulate a story about the same sequence of images, however, a “secret agent” was selected to participate within all the different groups. The secret agent was tasked with the objective of only using gender-neutral language when formulating the story. The other conversationalists were recorded to see if they followed suit with the gender-neutral language and if they applied certain gendered words or pronouns to the person they were describing. Shortly after, the participants were asked to complete the same implicit bias test as described above. The results were focused towards how many more women/men show implicit bias over men/women, and how many people exposed to the gender-neutral conversation completed the test with less or no bias over those who were not. My hypothesis is as follows, the use of gender-neutral language will promote the increased cognitive involvement of women which, in turn, will remove male bias in mental associations. By coming to this conclusion, or one similar, the importance (if any) of adopting gender neutral language into common vocabulary can be understood.

Results and Analysis

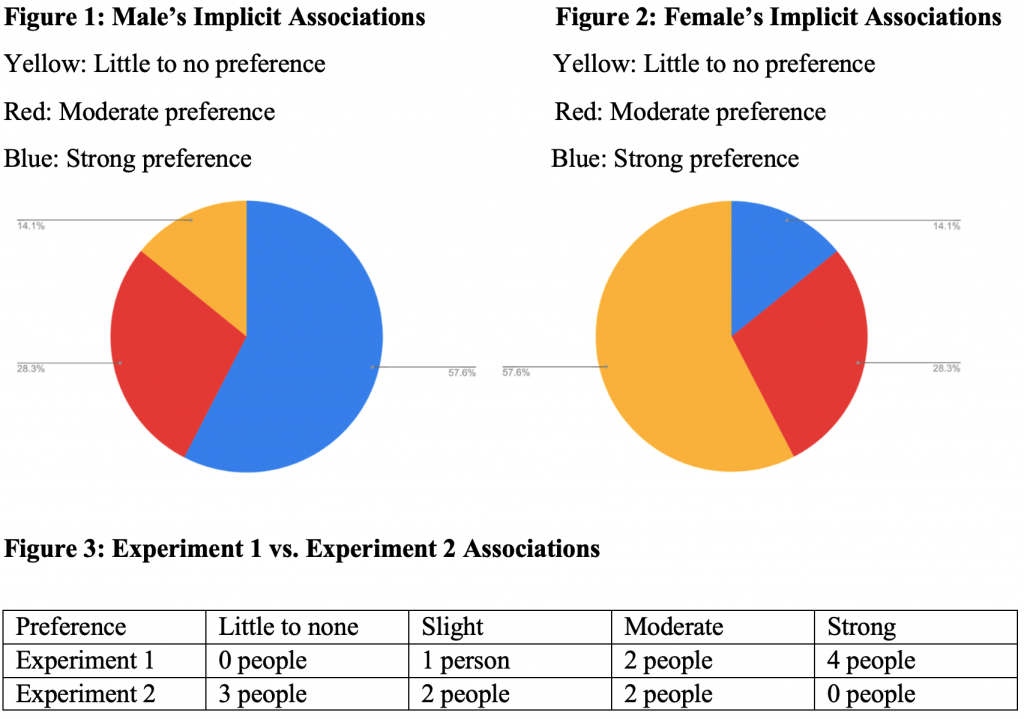

Throughout all groups, male implicit bias was assessed through the gender and career Implicit Association Test (IAT). Out of 14 people, half men and half women, males showed more automatic preference toward male and career than did females (Figure 1, Figure 2). As in Experiment 1, male implicit bias was assessed through the IAT after recording a previous exchange about the sequence of images while solely using gendered language. Compared to Experiment 2, where participants took the IAT test after having been exposed to gender-neutral language through the secret agent. As illustrated in Figure 3, people exposed to the gender-neutral language (Experiment 2) demonstrated less male implicit bias than those in Experiment 1.

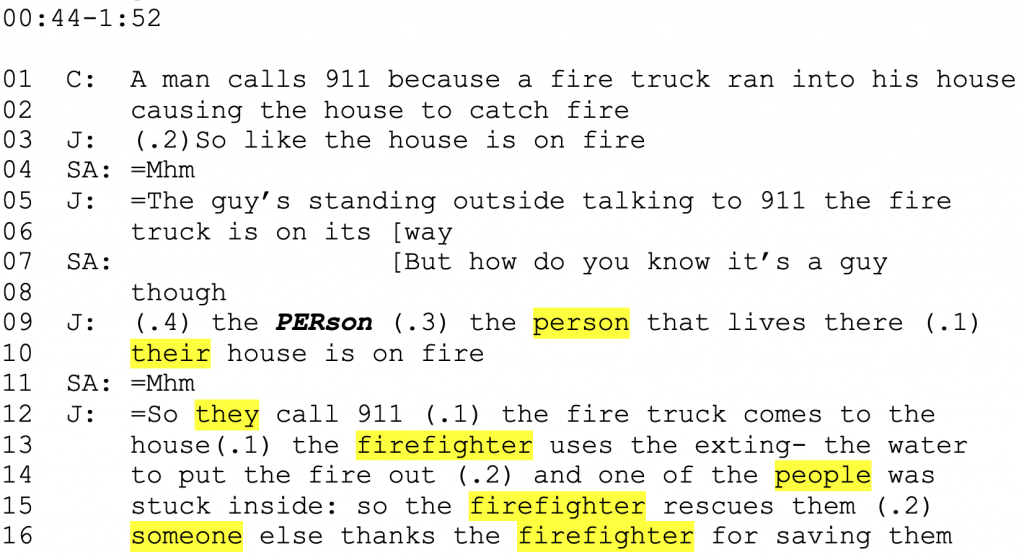

This example is an excerpt from a group in Experiment 2 after being presented with the images and asked to formulate a story. One member is asked to be the secret agent and is privately told to only use gender-neutral language when telling the story and to correct those who automatically associate a certain person with a certain gender. All members of the group are friends and are comfortable interacting with each other.

Cameron = C; Jade = J; Secret Agent = SA

The initial person, Cameron, immediately assumes and assigns the gender of the figure he is looking at in the picture to male (line 1). Jade interrupts him (line 3), presumably because she disagrees with how the story is supposed to begin. The secret agent agrees with Jade and prompts the continuation of her storytelling. Again, the gender of the figure is assumed and assigned male. The secret agent initiates repair, which indicates that the word used was problematic. The secret agent questions Jade about her reasoning behind referring to the person as a “guy”. The question does not signify a lack of understanding between the two conversationalists nor does it ask for clarification, instead the question is a means of conveying that using the term “guy” is problematic. Afterwards due to the silence, Jade understands that she may have mislabeled the figure’s gender, realizing that there are no significant distinguishing marks that allow her to label the figure a man. The secret agent has therefore created a conversation in which the terms that are considered problematic are avoided. The act of simply conveying issue with the use of gendered terms, prompts the other person to understand the problematic feature of their choice of words and correct any of their supplementary language. Because of the secret agent’s stance, Jade continues to solely use gender-neutral terms (lines 9-16) to describe the rest of the people involved in the story. Because the secret agent initiates repair about using the term “guy”, and Jade’s subsequent language avoids using gendered terms, a phenomenon is created that is effective in reducing male associations.

Discussion and Conclusions

Within discourse and conversation, people may be completely unaware of the implicit male bias they possess, especially when asked to draw their own conclusions about a nondescript person or thing. For many, it is an instinct to attribute certain words or images with a certain gender. But with the incorporation of gender-neutral speech styles, there can be a decrease in implicit male bias and thus an increase in the cognitive awareness of women. Along with the introduction of gender-neutral language, the recognition of a person’s own incorrect, automatic association reduces further male bias. As shown in Experiment 2, each member of the group begins with automatically assigning the male gender to the person in the sequence of images, but when their claim is disputed, each person recognizes their false assumption and changes their approach. From then on, most people were recorded to continue telling the story but now with the adoption of gender-neutral speech. So, with the understanding of their careless, implicit male bias, people open their minds to allow the possibility that both genders could suffice as the “person” or “firefighter”. Shortly after having been exposed to gender-neutral language within the conversation, those that followed suit performed better on the implicit bias test afterwards. Because of this, the importance of adopting gender neutral language into our common vocabulary becomes evident.

References

Gauhar, Z., Anderson, J., Li, S., & Fox, S. P. (n.d.). Why gender-inclusive language is important. Retrieved from https://www.dailyprincetonian.com/article/2016/09/why- gender- inclusive-language-is-important

Gender-Inclusive Language. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/gender-inclusive-language/

Harris, C. A., Blencowe, N., & Telem, D. A. (2017, December). What is in a Pronoun?: Why Gender-fair Language Matters. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5774006/

Jennifer, L, A., Ali, Bhardwaj, S., Burgh, G., Glen, … Portilla, L. (2014, January 16). BU Research: A Riddle Reveals Depth of Gender Bias: BU Today. Retrieved from http://www.bu.edu/articles/2014/bu-research-riddle-reveals-the-depth-of-gender-bias/

Lingquivst, A (2019, July 15). Reducing a Male Bias in Language? Establishing the Efficiency of Three Different Gender-Fair Language Strategies. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11199-018-0974-9

Rogers, A. (2019, August 15). Actually, Gender-Neutral Pronouns Can Change a Culture. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/actually-gender-neutral-pronouns-can-change-a-culture/

Tavits, M., & Pérez, E. O. (2019, August 20). Language influences mass opinion toward gender and LGBT equality. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/116/34/16781

Appendix

The implicit bias test administered to the participants:

Gender and Career: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html

The sequence of images for the formulation of the story: