Sarah Bassiry (Sky), Michelle Chan, Seohyung Hong (Alena), Christina Jang, and Jasmine Miranda

Through media platforms and conversations bilingual speakers engage in, we unconsciously and frequently code-switch across languages. Yet, the lingering interpretation of how style-shifting is done in Korean-English speakers continues to be scrutinized. In this study, researchers investigated observable linguistic patterns across three contrastive Korean-English populations and examined their code-switching temperaments within both languages. Six participants engaged in casual conversations with a researcher and were audio recorded in order to gather sufficient evidence. The participants were then asked to complete a background survey and had a follow-up interview post experiment. Detailed analysis from this study revealed that there were distinct results amongst all participants with cultural topic types and amount of code-switching occurrences. These preliminary results show that some participants had more occurrences of intrasentential code-switching in discussions that were culturally/contextually related to the embedded language. The study highlights how code-switching can influence and is more affected by the speaker’s linguistic identity than the topic of conversation.

Introduction and Background

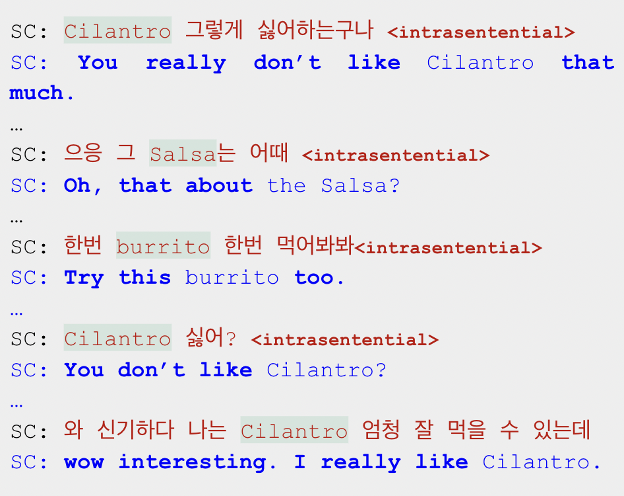

This study strives to investigate sociolinguistic patterns found in the code-switching of Korean-English bilingual college students, focusing on the frequency and cultural context of the code-switching as well as the type of code-switching utilized. Code-switching is defined as the capacity of multilingual to fluidly switch between several languages (Bullock & Toribio, 2009). The categories of code-switching types were interjections, intrasentential code-switching, and intersentential code-switching as defined by prior research in the field. Inter-sentential switching takes place in two different sentences with one sentence spoken in the primary language and the other one uttered in a second language; meanwhile, intra-sentential switching occurs within a sentence with a word specifically alternated to a second language (Mohamad Khalil & Mohd Shahril Firda, 2018). (1) and (2) below show examples of intrasentential and intersentential code-switching from the data recorded for this study.

- Intrasentential CS- example from Participant A (1:38~1:50)

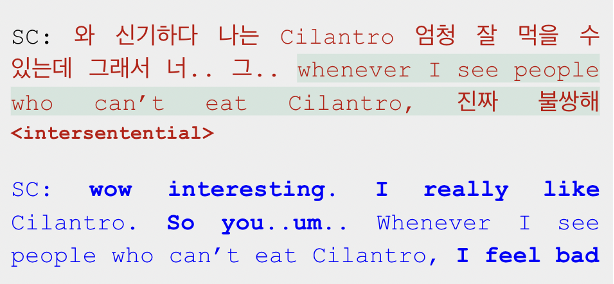

2. Intersentential CS- example from Participant A (1:51~1:58)

Image 2: Example of intersentential CS

The researchers followed the basis of the Matrix Language Frame Model (MLF) which holds the idea that code-switching has a matrix language and is the more dominant language that provides the morphosyntactic frame. Whereas, an embedded language is known as the language from which smaller elements are inserted (Myers-Scotton, 1933). Koban (2013) provides a detailed account of code-switching amongst Turkish-English bilinguals and has documented greater higher frequencies of intra-sentential code-switching as opposed to inter-sentential code-switching. This finding supports what the researchers hypothesize in this current study. Another implication the researchers examined was whether the participant’s language background and cultural background had any noticeable effect on their code-switching behavior.

Methodology

A total of 6 undergraduate students (mean age 22.16 years) studying at the University of California, Los Angeles, participated in the experiment. The population targets three different Korean-English bilingual college students (1st gen. Korean-Americans[A, B], 1.5 gen. Immigrant Korean/Korean-American [C, D], & Korean international students studying abroad in the U.S.[E, F]). The experiment was conducted through spontaneous casual-style speech in a one-on-one format with the researchers and was audio recorded. Upon completion of the experiment, relevant background information was collected from the participants through a background survey (age, country of birth, age of exposure to both languages, comfort language) and a follow-up interview with questions facilitated by the researchers. Researchers transcribed and translated applicable segments of the recorded material and then analyzed linguistic patterns in code-switching occurrences as well as findings tailored to sociolinguistic occurrences. The experiment per participant lasted an average of 30 minutes.

Results and Analysis

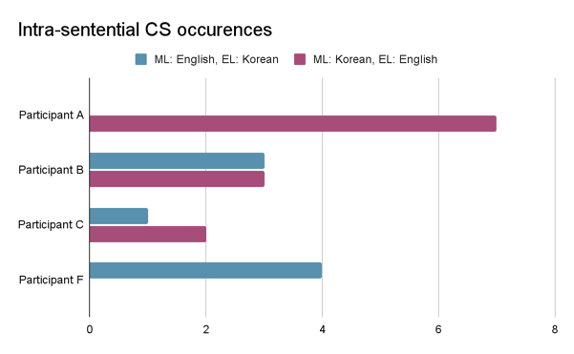

We found a two-way effect with intra vs. intersentential and the number of CS occurrences. This effect revealed that participants showed higher frequencies of intrasentential code-switching as opposed to intersentential which holistically supports what the researchers expected (see Figure 1). Participants A, B, C & F used this intrasentential shift in the middle of their sentences and without hesitation. This denotes a shift between Korean and English and shows that these participants are almost if not always unaware of the shift in this language (see Figure 2).

The most eye-catching result from Figure 2 reveals that Participant A showed no occurrences of code-switching as the matrix language being English, even though this same participant notated that his dominant language was English in the survey.

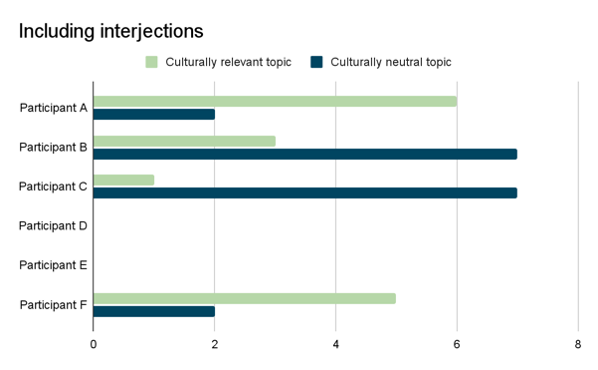

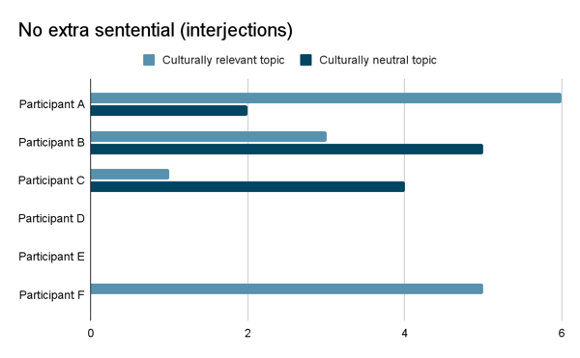

Figure 3 compares the CS occurrences according to the cultural relevance of the topic including intrasentential, intersentential, and extra-sentential occurrences. We can see from Figure 3 that participants B and C, showed more CS occurrences for culturally neutral topics which went against our hypothesis that people with code-switch more in topics culturally relevant to the embedded language. Even when excluding interjections, which we thought would less be influenced by the cultural relevance, we can still see such a result remains the same in Figure 4.

So for participants B and C, we underwent an additional in-depth analysis to see how their linguistic background influenced their CS behavior.

A comparison of participants A and B’s observed code-switching as well as their self-reported views of code-switching provides insight into the conscious and subconscious factors affecting their code-switching behavior and choices regarding their language use. Both where born and raised mostly in the USA and also expressed being most comfortable code-switching when speaking with other Korean-American friends. Prior research suggests that among bilinguals with social profiles including the identities related to both languages, code-switching may become the unmarked choice (Myers-Scotton, 1993), which seemed to be the case for some of the data examples we found in A and B.

Looking at the data example in image 3, participant A uses the English word “tutoring” for his first utterance even though the question was phrased in Korean. This could be attributed to him being less familiar with the Korean word “과외” but at the same time, it could also be because he uses CS as an unmarked linguistic choice. Also for his second utterance, it is notable that he lists two of the sports name in English but the latter two in Korean; obviously it isn’t that he doesn’t know the word “Soccer” and “Basketball” in English, rather he seems to be code-switching this time more unconsciously. The in-person interview revealed that he himself thinks he code-switches so often that it is almost second nature to him. So the CS occurrence in this excerpt is an example of CS being an unmarked choice.

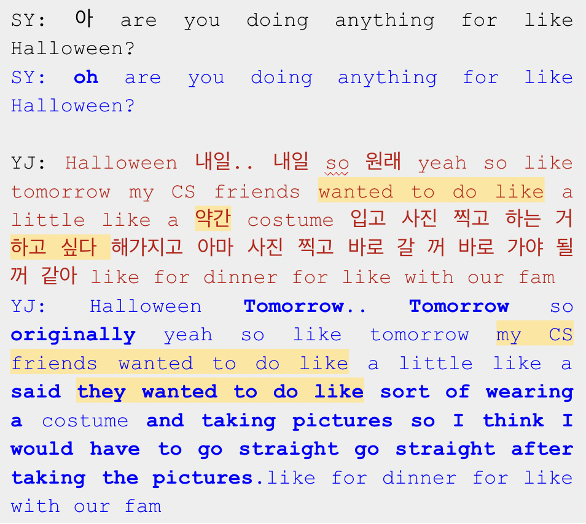

In participant B’s data example in image 4, it is worth noting that the part “wanted to do like” is repeated both in English and Korean in the intersentential CS with a change in the matrix language. This could potentially be a piece of evidence that for participant B, CS is such an unmarked choice that he would unconsciously switch the matrix language to Korean even though Halloween, being a culture-specific event, would be more easily expressed in English.

However, at the same time, the in-person interview revealed that participant A and B showed a difference when it came to the need to intentionally use more Korean. Participant A mentioned that “a Korean should be able to speak at least a decent level of the Korean language” (translated from Korean), which accounts for his intrasentential CS occurring mainly as Korean as the Matrix language. This also relates to the larger concept of a diaspora factor which adds an additional layer to bilingualism as “diaspora identities combine multiple points of identification, thus embodying and asserting how diversity and difference are lived and experienced as a process of entanglement” (McKittrick, 2009). Mills (2005) also discussed how in their 2001, 2004, and 2005 studies they found that in their target population of British-Pakistani bilingual diaspora that “the heritage language represents the community as being a crucial identifier and bond to the immediate and wider diasporic group (and that) their languages where crucial for maintaining their sense of identity as being both British and Pakistani” (Mills, 2005). While there are of course differences between each diaspora community, this theme of diaspora navigating their identity between cultures and the close connection to identity and community that languages tend to have for members of this type of community has shown up in many past studies on diaspora populations. The 1st generation Korean-American bilinguals (A and B) where the only subgroup in our study where both participants of that background showed frequent occurrences of code switching. Given the nature of diaspora populations and the results found in our study, our findings seem to support a conclusion that for Korean-Americans, code-switching is generally the unmarked choice and often used to index their Korean heritage as well as an in-group identity of being between two cultures as part of the Korean diaspora in America. Though Participants A and B had similar frequencies of code-switching overall, Participant A’s follow-up interview responses expressed a more conscious intention to index his Korean heritage as well as an in-group identity of being between two cultures as part of the Korean diaspora in America. Participant B on the other hand stated in the follow-up interview that he does not really feel the need to intentionally speak more Korean possibly attributing to his higher level of fluency and a longer period of studying the Korean language. Interestingly, Participant B actually had the highest rates of overall code switching, further showing how code -switching tends to be the unmarked choice within bilinguals whose identity is linked to both of their languages, such as bilinguals who are part of a diaspora population.

For participant C, she used English as the dominant language in the culturally relevant topic, Halloween, as opposed to the culturally neutral topic, buying tickets for a game, which shows that the American-culture-oriented topic did affect her linguistic behavior. However, at the same time, she showed fewer CS occurrences for the culturally relevant topic, which can be explained by her motivation for CS being a lack of proficiency in English for certain words which would occur regardless of the topic.

Another result noticeable in Figure 1 was that participant D and E did not show any occurrences of CS at all. In the interview, participant D said that even if the person they were speaking with was a Korean-English bilingual, he would consciously not code-switch if the topic was serious because there would be the need to convey his intentions in a more clear-cut manner through his native language, which seemed to be the case for the 40-minute conversation recorded.

On the other hand, the participant’s usual frequent use of CS with the interviewer and his response that he feels the need to consciously speak more English in the States to improve his English-speaking skills implies that CS is a marked linguistic choice for him to index his identity as a more fluent English-speaking international student in a community where the majority of the people speak English as their mother tongue. This relates to the social status of English in Korean society. In Korea where western countries, mainly the United States, are viewed as “superpowers” due to political and historical reasons (Cho, 2021). English has been shown to be greatly publicized and commonized especially in educational institutions (Choi & Kim, 2021). In other words, speaking English fluently symbolizes higher social status thus it developed an advanced elite image. It has been observed that bilingual immigrant families in the US are experiencing linguistic discrimination in that they have accents when speaking English which is labeled as broken and unintelligent (Tedx Talks, 2018, 2:30). It may explain the motivation of participant D trying to intentionally speak more English as he can to purposely present an international bilingual elite image.

Participant E responded that she would avoid code-switching to English when talking with native Korean speakers even if they were fluent in English. It has been observed that code-switching can be regarded as showing off when the interlocutors have unequal language proficiency (Fangzhe, 2019). In order to prevent being interpreted as bragging about her language ability, participant E intentionally avoids code-switching. Thus to her, CS was shown to be the marked linguistic choice and the markedness entailed a more negative connotation as a person who feels the need to “show off” their English or seem more “American”. And through this linguistic behavior, she may be able to feel a sense of belonging with her immigrant friends whose dominant language is Korean.

Thus both participants showed that the agency of the speaker to index (or not to index) a certain identity intervenes in the choice of an absence of CS, which aligned with our analysis for participant A, B, and C.

Additionally, the 1st generation immigrants tended to show more CS occurrences compared to international students which relate to how in previous studies it has been proven that language was affected by people’s aspirations, stances, and attitudes (Tedx Talks, 2014, 11:05). In other words, the linguistic behaviors of the participants would be affected not only by their current community of practice but also by the in-group they expected themselves to be placed in the future. So for the former group, because they aspired to stay in the States for the rest of their lives, they would be frequently exposed to a linguistic environment in which CS would be the unmarked choice such as with their college Korean American friends or with their family. For the international students, they would only be staying in the States for less than a year, after which they would return to South Korea where CS would generally be accepted as a marked choice even sometimes with negative connotations.

Conclusion

This experiment provided an opportunity for us to closely examine code-switching patterns in bilingual Korean-English speakers. The researchers pondered on observable linguistic patterns in three contrastive Korean-English populations in relation to code-switching behaviors. Thorough analysis of the findings indicates different relationships between linguistic behaviors and sociolinguistic identities. The overall analysis from this study reveals that code-switching is in fact more affected by the speaker’s linguistic identity rather than what topic is being conversed. The findings provide sufficient evidence that people index code-switching as part of the in-group identity and thus accepting code-switching as an unmarked choice would produce more code-switching occurrences comparatively to those who code-switched to index a marked linguistic pattern.

References

Bullock, B., & Toribio, A. (2009). Themes in the study of code-switching. In B. Bullock & A. Toribio (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-switching (pp. 1-18). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511576331.002

Cho, J. (2021). English fever and American dreams: The impact of Orientalism on the evolution of English in Korean society. English Today, 37(3), 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026607841900052X

Choi, Tatar, B., & Kim, J. (2021). Bilingual signs at an “English only” Korean university: place-making and “global” space in higher education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(9), 1431–1444. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1610353

Fangzhe. (2019, May 7). Code-switching: showing off? Educational Sociolinguistics. https://bild-lida.ca/educationalsociolinguistics/uncategorized/code-switching-showing-off/#:~:text=In%20this%20case%2C%20code%2Dswitching,that%20you%20are%20showing%20off.

Koban, D. (2013). Intra-sentential and inter-sentential code-switching in Turkish-English bilinguals in New York City, U.S. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 1174–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.173

McKittrick, K. (2009). Diaspora. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 156–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008044910-4.00938-x

Mills, J. (2005). Connecting communities: Identity, language and diaspora. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8(4), 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050508668610

Mohamad Khalil, S., & Mohd Shahril Firda, M. S. Z. (2018). Inter-sentential and intra-sentential code switching in parliamentary debate. International Journal of Modern Languages And Applied Linguistics, 2(4), 29–31. https://doi.org/10.24191/ijmal.v2i4.7691

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Common and uncommon ground: Social and structural factors in codeswitching. Language in Society, 22(4), 475–503. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404500017449

Tedx Talks. (2014, Nov. 21). TEDxDublin – Vera Regan – What your speaking style, like, says about you [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jAGgKE82034&t=593s

Tedx Talks. (2018, July 25). TEDxWWU – Karen Leung – Embracing multilingualism and eradicating linguistic bias [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S8QrGsxeEq8