Sarah Arjona, Yeeun Heo, Erika Yagi, Minyoung Yoon, Bryan Zhao

Have you ever imagined growing up next to the pyramids or the Eiffel tower? Some Third Culture Kids (TCKs) do so without being Egyptian or French, because they live abroad with their parents. Although extensive research has been done on code-switching, not a lot of this research has focused on code-switching in TCKs. This study explores the code-switching of Spanish English multilingual TCKs in formal and informal settings. To test our hypothesis that TCKs code-switch more often in informal settings among their peers, we conducted one-on-one interviews and a group activity with three tween and teen Spanish English multilingual TCKs over Zoom. We analyzed the frequency of their code-switching as well as the length of their code-switching. Our findings suggest that TCKs do code switch more often in the informal setting but it may not only be influenced by setting type but also by age and attitude.

Introduction and Background

If your parents are from Spain, but you grew up everywhere else like Zimbabwe and Vietnam, you would be considered a Third Culture Kid (TCK). TCKs are those regarded as growing up outside of their parents’ home countries as in the example above, and they are often known to be multilingual due to their diverse backgrounds (Barker & Moore, 2012; Bonebright, 2010; Pollock et al., 2017). There are currently over 230 million expatriates in this world, and many are accompanied by their children who would be considered TCKs (United Nations, 2019). TCKs can impart other important skills, such as adapting effortlessly to environmental changes, relating easily to other cultures, having strong communication skills, and being open-minded.

Although many of the TCK studies are conducted around English speakers, this research looks at Spanish speaking families, as Spanish is the language with second most native speakers in the world, surpassing English (Ahearn, 2021). However, while there are over 8000 English speaking international schools around the world, Spanish based schools outside of Spanish-speaking countries are not as accessible (Sharma, 2016). So how would they go about using their language skills, especially code-switching?

Code-switching is defined as interchanging among different languages in a speech (Ahearn 2021), or using one’s mental lexicon to a fuller extent. Code-switching occurs in both formal and informal settings (Jacobson 2002). Informal settings can be with friends, family and peers, and formal settings with strangers in structured settings (Jacobson 2002). Code-switching is often motivated by social factors such as the topic or the speaker’s attitude toward the topic, identity creation and solidarity (Myers Scotton, 1993; Van Herk, 2017).

Since TCKs are extremely adaptable, they may show some code-switching in both settings. Our hypothesis is that they are more likely to code-switch in an informal setting and more frequently so when surrounded by peers who share one or more languages.

Methods

Three TCKs, Maria, Juan, and Ana were recruited for this research. All three of them are multinational, but have at least one Spanish parent whom they speak Spanish with. Maria and Juan also speak French at home, whereas Ana speaks only English and Spanish. All three have attended English-speaking schools and are thus multilingual in at least English and Spanish. They are all TCKs as they have lived abroad for the most part of their lives, including in countries such as Ethiopia, Haiti, and Sierra Leone.

These three TCKs participated in two meetings, one formal and one informal setting. We used Jacobson’s definition of these settings, where the formal setting is defined to be with strangers in a structured, official environment, and the informal setting with friends and family (2002).

Formal Activity: One-on-one zoom interview (15 minutes)

TCKs were interviewed about themselves by a Spanish and English-speaking interviewer in both languages. The language in which the questions were posed alternated between English and Spanish and the TCKs were encouraged to answer in both languages. The purpose of this interview was to induce the TCKs to use proper nouns and speak of familiar experiences, providing them a situation to code-switch.

Informal Activity: Group Game Night (30minutes)

All three TCKs participated in a game night together, hosted by the same interviewer from the prior meeting. The game consisted of building two stories; one in English and one in Spanish as the matrix language. The task was to continue a single storyline by taking turns to say a part for 15 minutes in English and 15 minutes in Spanish. Students were given no further instruction about whether they could code-switch or not. This task allowed the participants to feel comfortable and enjoy the meeting, which we hypothesized initially would lead to more frequent use of code-switching.

Results/Analysis

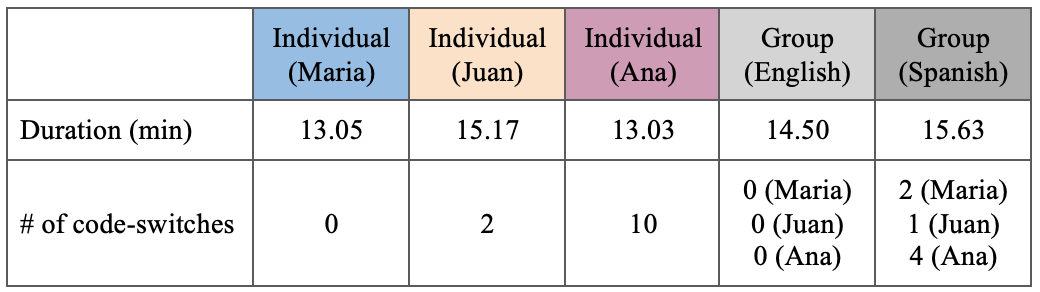

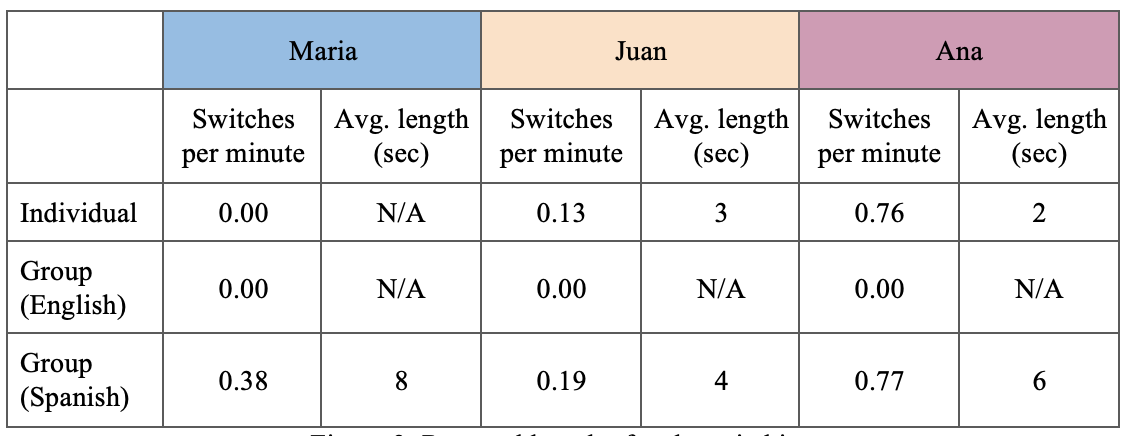

To capture our results, we counted the number of code-switches in each interview and took note of the duration of each segment. This data is recorded in Figure 2 below. We also cataloged each instance of code-switching by noting its timestamp, duration, and verbal content.

We first analyzed our data by calculating the rate of code-switching per minute for each participant in each setting by dividing the number of code-switches by the length of time the participant spoke in the segment. Note that in the group interviews, each participant spoke for approximately the same amount of time. We also calculated the average length of each code switch, with the same segmentation. Figure 3 displays these findings below.

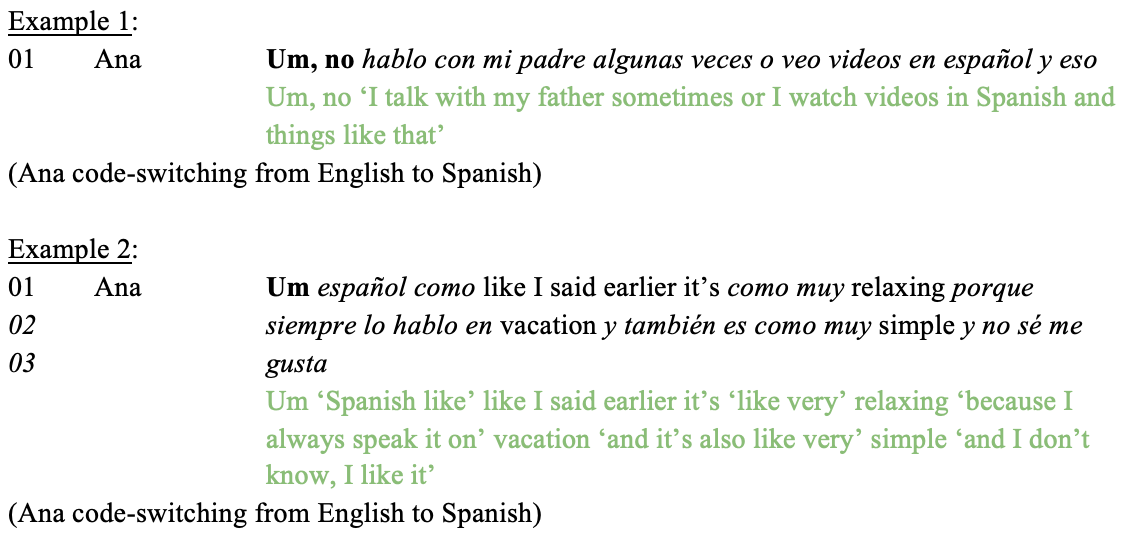

During the individual interviews, Ana code-switched the most frequently out of the three participants, at a rate of 0.76 times per minute and an average length of 2 seconds per code-switch. Ana’s number of code-switches from English to Spanish and Spanish to English were about the same. However, her English to Spanish code-switchings consisted of almost exclusively filler words and discourse markers. For example, Ana would often say “Um..” in an English accent before continuing to answer her question that was asked in Spanish as in the examples below during her individual interview recording.

Moreover, she used English starter words such as “Probably…” and “Like…” before answering in Spanish. On the other hand, her Spanish to English code-switching included more meaningful utterances and lasted for a longer period each time. The Spanish to English code-switchings include words and even whole phrases to enhance her answer. Juan had two instances of code-switching during his individual interview, which were also filler words. Lastly, our third participant, Maria, did not code-switch at all during her individual interview.

None of the participants code-switched during the English group activity. The direct correlation for having more code-switching during the Spanish activity isn’t clear, but there are a few factors that can be discussed. The strongest factor might be that students are more comfortable with English in general. They also confirmed that English is their strongest language during the interview. Another may be because the interviewer herself did little to no code-switching throughout the whole study, at least not at a word level. Finally, the interviewer’s Spanish variety is different from the interviewees (which will be further elaborated under limitation), which may have an impact on the participants’ use of Spanish.

However, for each participant, both the rate of code-switching and the average length of a code-switch were greatest during the Spanish group interview. Ana, who code-switched the most compared to her peers during her individual interview, did so even slightly more often during the Spanish group interview at a rate of 0.77 times per minute. The length of her code-switching was also significantly longer during the latter interview, at 6 seconds on average compared to 2 in the former. Juan, who code-switched a few times during his individual interview, also raised his rate of switching during the Spanish group interview to 0.19 switches per minute, and the average length to 4 seconds per switch. Finally, even Maria, who demonstrated no code-switching during the other interviews, did have a number of switches during the Spanish group interview, at a rate of 0.38 times per minute. Interestingly, Maria also displayed the highest average length of a code-switch, at 8 seconds per switch.

Our hypothesis suggests that the individual interviews invoked less code-switching because they were more formal and were also the first time for the participants and the interviewer to meet and have a real conversation. The individual interviews consisted entirely of questions and answers, which limited free interactions with the interviewer and the interviewees. On the other hand, the group activity was more in the format of a fun conversation where participants spoke relatively freely and even interrupted each other to add and comment on things. Some of the reasons why they may not have code-switched as often during the individual interviews could be explained by other factors as well. Age may have played a role because our youngest participant, Ana, was the one to code-switch most often in both the formal and the informal meetings. Moreover, Juan, the oldest of the participants, acted as a facilitator throughout the group meeting to correct the other participant’s Spanish utterances. There was an instance where Maria struggled to find the Spanish word for ‘emotional’ and Juan stepped in to help and encourage Maria to say the corrected phrase.

Another instance was when Ana said “el cure” – using the masculine form for ‘the’ and then the English word “cure” – and Juan corrects her by saying “la cura” with the correct feminine form of “the,” correcting both her improper form of the article and her use of the English “cure.” Participant’s intentions and plans may also have affected the frequency of code-switching, as in the Ted Talk with Vera Regan (2014). Juan, who code-switched the least out of all three participants, plans to go to Spain in the future for college. His plans on moving to Spain may have had an impact on his view of the Spanish language, leading him to have a more practical take on the concept of language.

Discussion and Conclusions

By looking at TCKs in formal and informal settings, we observe their code-switching patterns, which is significant because it contributes to our understanding of TCKs as extremely adaptable and open-minded. The data supports our hypothesis that TCKs code-switch more in informal settings among their peers because participants code-switched more often in the group activity than in the one-on-one interviews. Additionally, there were correlations with age in that the oldest participants, Juan and Maria, code-switched the least and more at the phrase and sentence levels. The youngest participant Ana, on the other hand, code-switched the most and more at the word level. We also saw a correlation between less code-switching and attitude in the oldest participant, Juan, as he tended to code-switch the least. Juan made efforts to speak only either Spanish or English at a time and he guided the other two participants by providing the appropriate Spanish word when the other participants code-switched to English from Spanish at the word level. These behaviors may be attributed to Juan’s assumption of a facilitator role during the group activity, his practical view on language, and his future plan to live in Spain.

Future Directions

In order to further explore age as a significant factor in code-switching, the study can be replicated with different age groups. The focus would be on whether there are patterns between older participants and less code-switching as well as on the level of code-switching. Another direction the study can take is to compare code-switching across groups with different attitudes. For example, we could compare code-switching between a group of participants that have future plans to live in a Spanish-speaking country and a group that doesn’t have such plans. Lastly, the study can be expanded to compare across different varieties of Spanish, matching participants with interviewers that speak their variety of Spanish. This study focuses on speakers of a variety of Spanish from Spain. Future studies may expand into different varieties of Latin American Spanish as well as varieties of U.S. Spanish and more.

Limitations

It is worth mentioning that although the interviewers and participants both spoke English and Spanish, they spoke different varieties of Spanish. While the participants spoke Spain Spanish, the interviewer spoke Los Angeles/Southern California Spanish heavily influenced by Mexican Spanish and Guatemalan Spanish varieties.

Additionally, most of the questions asked during the one-on-one interviews were yes/no questions. Another thing to consider is that the interviewer did not code-switch. All these factors may have affected the creation of a setting that allowed for a more spontaneous elicitation of code-switching.

References

Ahearn, Laura. 2021. Living Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Barker, G. G., & Moore, A. M. (2012). Confused or multicultural: Third culture individuals’ cultural identity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(4), 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.11.002

Bonebright, D. A. (2010). Adult third culture kids: HRD challenges and opportunities. Human Resource Development International, 13(3), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678861003746822

Herk, V. G. (2018). What is Sociolinguistics? (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jacobson, R. (2002). Broadening Language Use Options in Formal Discourse: The Malaysian Experience. Retrieved July, 13, 2014.

Jess. (2018, February 6). Employee benefits & third culture kids: What do global citizens want most from employers? Pacific Prime’s Blog. https://www.pacificprime.com/blog/third-culture-kids.html

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Common and uncommon ground: Social and structural factors in codeswitching. Language in society, 475-503.

Pollock, D. C., Van Reken, R. E., & Pollock, M. V. (2017). Third Culture Kids: Growing up among worlds (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Regan, V. (2014, November 21). What your speaking style, like, says about you. Tedx Talks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jAGgKE82034&t=593s&ab_channel=TEDxTalks.

Sharma, Y. (2016, February 24). Asia drives demand for international schools. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-35533953

United Nations. (2019). International Migrant Stock 2019. United Nations Population Division | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp