Britney Lam, Iris Lin, Alice Wang, Julia Zhou

Romance is a common element across all genres of film. Whether it is an action movie, a comedy, adventure, or drama, romance is often included within the main plot. Films are created with a target audience, such as age or gender. Our research question emerged: how is romance portrayed differently in movies that are intended to cater to different audiences? Specifically, what linguistic differences can be observed between the romantic scenes? Through the analysis of 10 total films, we found that MLUs in action and romance movies did not significantly differ from each other, though MLU in dialogue succeeding romantic scenes are indeed longer in romance movies.

Introduction and Background

Stereotypically, romantic and action movies are catered towards the female and male genders, respectively. Although a lot of people, regardless of their gender identification, watch both action and romance movies, such gendered catering may still continue to exist, and characters may still exhibit different behavioral and linguistic patterns across the two genres. One specific type of scene may be the most affected by the genre of the movie — romantic scenes. If the language of romance scenes is indeed different between action and romance films, these stereotypes may affect the audience’s perception of different genres of movies, which in turn intensifies the stereotypical association between certain behaviors with one specific gender. Consequently, our research intends to observe whether the language used in romantic scenes is indeed different between romantic and action movies.

Previous literature had tackled language style and non-linguistic elements (eye contact, body language) in romance and action movies respectively, but none had compared romance to action films in terms of dialogue length (Dewi et al., 2020; Burns et al., 2009). In a study done by Dewi et al. (2020), the word choice of characters in action films was examined to identify linguistic style patterns; their methods largely inspired our research design to study character dialogue. In research done by Burns et al. (2009), action movies were found to significantly differ from other genres in terms of actors’ behavior (e.g. fewer smiling); this made us wonder how linguistic elements may differ as well.

Thus, we chose to focus on the romance and action genres given that, stereotypically, action movies are catered more to the male audience and romance movies are catered more to the female audience (Brandenburg et al., 2004). Furthermore, building off of research done by Grant et al. (2001) that found males and females are portrayed to behave stereotypically in films, we sought to address the gap among these individual research studies by examining the linguistic features of both romance and action films, then comparing the two to identify differences between the dialogue in romantic scenes catered to different audiences, and whether or not they align with male and female stereotypes.

We set out to answer this by examining how Mean Length Utterance (MLU), a tool used to judge meaningful dialogue length, would differ before, after, and during romantic scenes between action and romance films. MLU is mainly utilized in previous research to study toddlers’ speech, but our research decided to utilize this novel measurement for our linguistic analysis, as it provides insight into the amount of information-rich utterances (Brown, 1973).

We hypothesized that romantic scenes in action films will have shorter MLUs that precede, succeed, or occur during intimate behavior, while romantic scenes in romance films will have longer MLUs that precede, succeed, or occur during intimate behavior. By examining linguistic differences between films catered to males versus females, we hoped to identify and address the stereotypical use of language in movies of action and romance genres, and subsequently propose changes to filmmaking that discourage reinforcing such stereotypes.

Methods Design

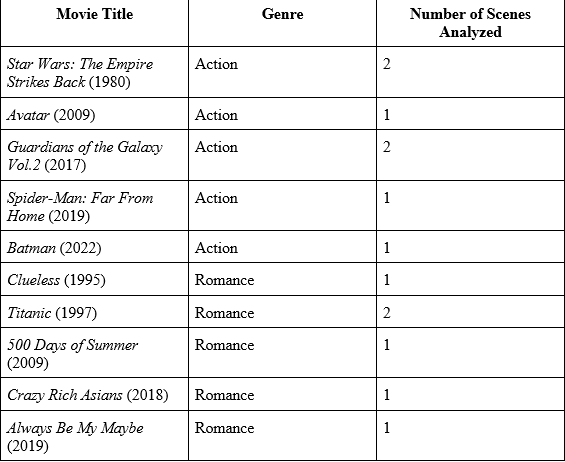

We analyzed the dialogue between heterosexual couples in 10 English-language films released between 1980 and the present (see Table 1). These films were chosen because they were high-grossing films that have accessible scripts. In our chosen romance and action films, we investigated romantic scenes that included direct or indirect displays of affection between two characters.

Direct examples included verbal confessional acts of love, including the explicit usage of the words “love” or “like.”

Indirect examples included verbal acts without “love” or “like” and behavioral displays of intimacy, which included sharing personal thoughts and emotions, as well as hugging, holding hands, and kissing. For example, in this scene in Avatar (2009), the main characters indirectly stated their affections towards each other:

Neytiri: You are Omaticaya now. You may make your own bow from the wood of Hometree. (she looks away) And you may choose a woman.

The Amazon warrior trying so hard to sound casual. Jake suppresses a smile.

Neytiri: We have many fine women. Ninat is the best singer —

Jake: I don’t want Ninat.

Neytiri: There is Beyral — she is a good hunter —

Jake puts his fingers on her lips to stop her.

Jake: I’ve already chosen. But this woman must also choose me.

She takes his hands and their fingers intertwine, moving gently over each other.

Neytiri: She already has.

Three variables, dialogue preceding the romantic scene (“MLU Preceding”), during the romantic scene (“MLU Love”), and succeeding the romantic scene (“MLU Succeeding”), were taken from film transcripts and analyzed for their MLUs. In our research, we calculated MLU by the number of morphemes divided by the number of utterances in speech.

For example, we took this preceding statement before the romantic scene from Crazy Rich Asians. This was the dialogue before the intimate behavior of a marriage proposal.

Nick: Rachel Chu. Will you marry me and make me the happiest man in this world?

(16 morphemes and 2 utterances)

16/2 = 8 MLU

We defined utterance as speech without pause. For example, Nick speaks, pauses, and then speaks again after saying Rachel’s name – this would be considered two utterances. The word “happiest” would be counted as two morphemes, split between “happy” and the suffix “-est.” Consequently, there are 2 utterances in total, with 16 morphemes, resulting in a MLU of 8.

Additionally, another variable, “Love Presence”, was recorded for every scene we analyzed, which indicated whether a direct display of affection was present in the scene.

We repeated this process for all 10 of our films (5 romantic, 5 action) by examining the transcripts and counting the number of occurrences the words “like” and “love” were explicitly used.

Results and Analysis

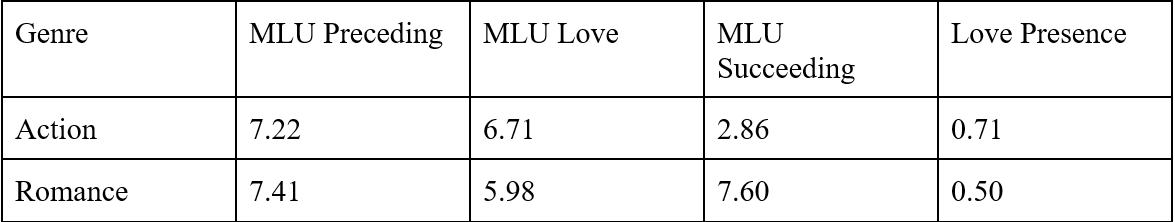

Firstly, we can look at the descriptives of our data (see Table 2) — The average number of MLU Preceding, MLU Love, MLU Succeeding, and Love Presence in both action and romance movies.

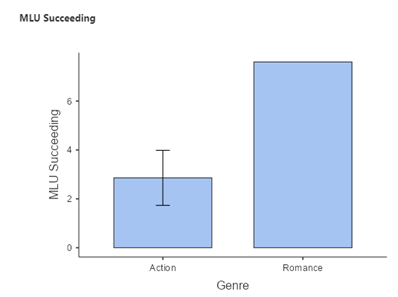

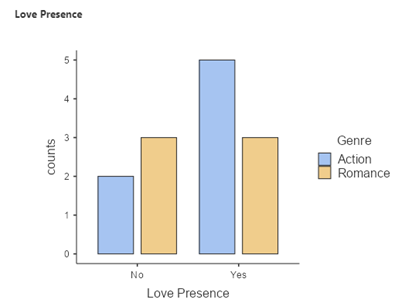

As can be seen in Table 2, notable variables that show a difference are MLU Succeeding and Love Presence. Romance movies seem to have more MLU Succeeding than action movies, which means that after the main characters confess their love for each other, romance movies seem to have longer and more meaningful utterances. Moreover, action movies seem to have a higher frequency of Love Presence than romance movies, meaning that characters in action movies may more often state their love directly.

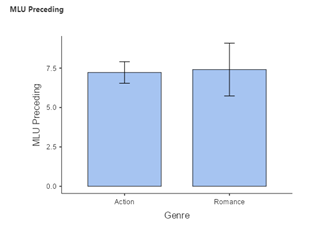

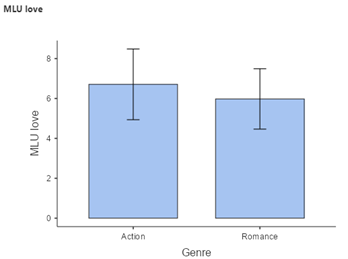

Subsequently, four separate independent samples t-tests, with a 95% confidence interval for the mean difference, were conducted to compare if the two genres significantly differ from each other in their MLUs. All four tests revealed non-significant results, showing that in romance and action movies, MLU Preceding (t(9) = -.11, p = .915), MLU Love (t(5) = .30, p = .777), MLU Succeeding (t(4) = -1.72, p = .161), and Love Presence (t(11) = .75, p = .471) all do not significantly differ from each other. Figures 1-4 below visualize the results of the four t-tests.

Discussion

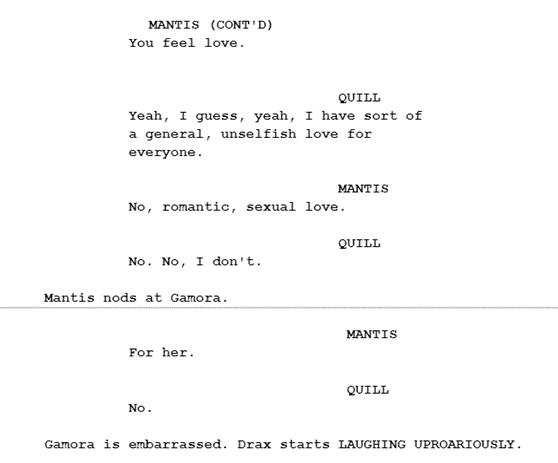

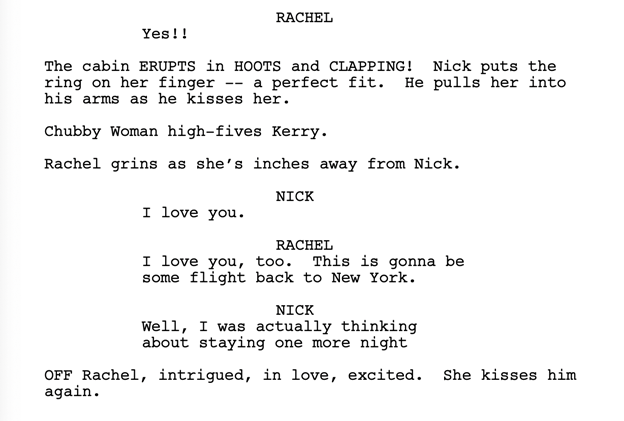

Contrary to our hypotheses, our results showed that romance and action movies did not differ significantly in their lengths of utterances. There is a trend towards significance for MLU Succeeding, which indicates that romance movies may contain more information after the confession of love. As for the reason why there may be such a trend, maybe romance movies tend to describe what happens after the characters state their affections towards each other, while action movies tend to view the confession of love as an ending for the romance elements and focus on the “main plot” afterwards. For example, in the action movie Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (2017), one romantic scene ended as soon as the main character Quill’s affection towards the other character, Gamora, was revealed by another character, causing that the scene did not have any morphemes for MLU Succeeding (see Fig.5). This specific absence of any utterances after the MLU Love might be due to that a) the focus of the movie was not on the romance, but rather the main characters defeating the villains; b) Quill tries to deny his affections, and the scene quickly ended to express his embarrassment. In contrast, in the romance movie Crazy Rich Asians (2018), the main characters continued to express their excitement and happiness after accepting the marriage proposal, causing the MLU Succeeding to be particularly long (see Figure 6). Still, this trend can only be applied to our sample, and cannot be generalized to all the romance and action movies in general because of our limited sample size.

Because of time and resource constraints, our study has several limitations. Firstly, our sample size (10 movies and 13 scenes in total) may have limited the power of our data, having more scenes and more movies may have yielded more statistically significant results. Secondly, because we selected romantic scenes where the main characters’ affections were revealed, the linguistic variables were sometimes missing. For example, the scene from Guardians of the Galaxy Vol.2, as we mentioned before, did not contain any MLU Succeeding. These partially incomplete datasets may have further limited our statistical power. To solve this flaw in data collection, we would recommend future studies to collect more data to remedy the fact that some romantic scenes do not contain any utterances for succeeding statements of love. Alternatively, future studies can define and select romantic scenes differently, so they can control and ensure every scene will contain utterances for all three variables. Despite these limitations, our methods of investigating the MLUs of scenes are novel, as no previous research directly compared romantic scenes in romance and action movies, and little, if any, research on linguistic analyses of movies selected MLU as their method.

Given that our results showed no significant difference between how romance and action movies depicted romance, it will be interesting to look at how the two genres may have converged and become more similar over time. Comparing romance and action movies chronologically based on their release date may reveal a pattern or trend of change. In fact, our results may hint such chronological changes, as newer action movies (Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (2017) and Spiderman: Far From Home (2019)) contained more statements of love than compared to older action movies (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980)). This difference we observed can be further explored by creating a study focused on collecting love statements from romance and action movies across time, and then comparing word choice or MLU.

Additionally, MLU is only one way of investigating the length of utterances. Future studies can use different methods. For example, linguistically, future studies can look deeper into a) how main characters explain their reasons for loving the other character; b) if main characters express their hopes of moving forward in their relationship; (c phonetically, their intonation when confessing their love. Non-linguistically, future studies can look into the main characters’ body language and eye movements when they are confessing their love. Behavior before, after, and during romantic scenes can be analyzed, as well as the setting and time of day.

Finally, recent literature has observed recent efforts by films to depict less stereotypical portrayals of romance (Brandenburg et al., 2014). There may be an emerging trend of combatting traditional narratives, which would be an interesting area of study to explore. In line with the idea of studying films chronologically across time, future research can aim to examine differences between romance and action films released in recent years and compare them to one another or to older films. If romance and action films are stereotypically catered towards female and male audiences, then it is entirely possible that films have changed over time to cater to changing societal standards. For example, if there is more demand for a female lead that is portrayed as independent and strong-willed, movies with romantic scenes may adapt linguistically to that. It will be an interesting field of study to identify these emerging patterns and trends.

References

Brandenburg, J. D., Dodds, L. A., Harris, R. J., Hoekstra, S. J., Sanborn, F. W., & Scott, C. L. (2004). Autobiographical memories for seeing romantic movies on a date: romance is not just for women. Media Psychology, 6 (3), 257-284.

Brown, R. (1973). Development of the first language in the human species. American Psychologist, 28(2), 97-106. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034209

Burns, A. C. (2009). Action, romance, or science fiction: your favorite movie genre may affect your communication. American Communication Journal, 11(4), 1-17.

Cameron, J. (1997). (Director). (1997). Titanic [Film]. 20th Century Fox; Lightstorm Entertainment; Paramount Pictures.

Chu, John. M. (Director). (2018). Crazy Rich Asians [Film]. Color Force; Electric Somewhere; Ivanhoe Pictures; SK Global; Starlight Culture; Warner Bros. Pictures.

Dewi, N. M. A. J., Ediwan, I. N. T., & Suastra, I. M. (2020). Language style in romantic movies. Humanis: Journal of Arts and Humanities, 24(2), 109-117.

Grant, B. K. (2001). Strange days: gender and ideology in new genre film. In M. Pomerance (Ed.), Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls: Gender in film at the end of the twentieth century (pp. 184-199). State University of New York Press.

Gunn, J. (2017). Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 [Film]. Marvel Studios.

Kershner, I. (1980). Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back [Film]. Lucasfilm Ltd.