Iscelle Abad, Zhuoen Li, Ira Throne, Ryan Tsai, Max Yudowitz

With the ongoing invasion of Ukraine, language in the country is changing. In response to the war, many natives have expressed a desire to switch their primary language in daily life from Russian to Ukrainian. Although it’s been a while since it was conducted, the 2001 All-Ukrainian population census estimated that roughly 29.6% of the Ukrainian Population spoke Russian as a native language, equalling roughly 14.3 million people. Since there has been no new census conducted in over 10 years, it’s hard to approximate the exact number of Russian and Ukrainian speakers today. However, a recent 2022 national poll conducted by the independent sociological research group RATING (Рейтинг) showed that, among respondents, in the last 10 years the number of native Ukrainian speakers has steadily grown from 57% in 2012 to 76% in 2022 with the percent of native Russian speakers at around 20%.

Given that a fair number of the population are not completely fluent in Ukrainian, the attempt to switch over has not been easy for everyone. The adjustment of switching primary language within a community is usually a long-term process spanning generations, but given the unique circumstances, many Ukrainians are going through it at an accelerated pace within just a few months.

Since this is a turning point for Ukraine linguistically, some crucial questions are necessary. How are people going through this process? What aspects of the transition come easier to people, and what struggles are they dealing with during this transition? Are there some sort of unique transitional stages that Ukrainians are going through in the same way?

These are the questions that prompted our research. An unprecedented level of media availability allows insight into how some speakers are utilizing code-switching (changing between different languages when speaking) in their daily lives today, almost in real-time. Some anecdotes that can give insight into how some Ukrainians are experiencing this change can be read in interviews in this article: Enemy tongue: eastern Ukrainians reject their Russian birth language | Ukraine | The Guardian. Another example is the subjects of our study, Ukrainian vloggers, who have made a noticeable shift from primarily speaking in Russian to primarily speaking in Ukrainian. Initially, before conducting this study, we anticipated that the subjects at first would most frequently code-switch from Russian to Ukrainian when they are telling jokes or just by inserting common words into their conversation.

The subjects of our study are three YouTube bloggers from a channel called “Lions on a Jeep” who spoke almost exclusively in Russian until after the full-fledged invasion of Ukraine started. They’re men in their late 20s – early 30s and were familiar with Ukrainian before, although they didn’t seem to actively use it on a daily basis. Starting March 3, 2022, they began to record live streams in their effort to collect donations for the Ukrainian military. Their first 2 streams were almost completely in Russian, but during the 3rd stream they started switching to Ukrainian at different rates. As of right now, they are still recording their streams and have transitioned to speaking Ukrainian for the most part. We collected over 70 speech samples from several live streams of theirs. The frequency, amount of videos in a short period of time, and the unedited and casual format of the conversation helped to consistently and closely analyze the transition.

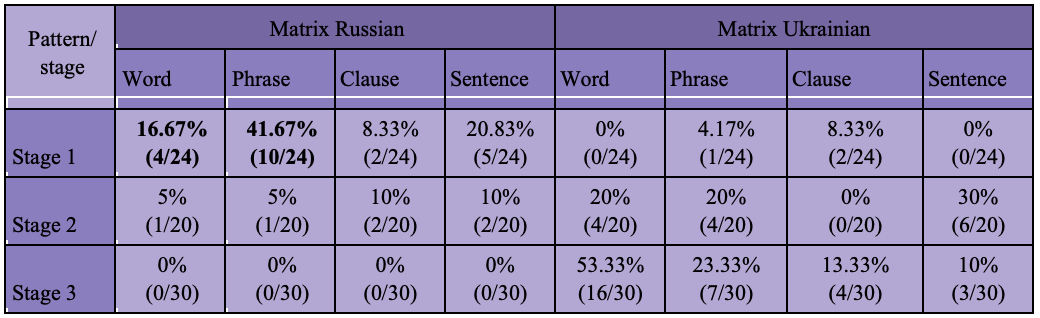

Before gathering data, we divided the transition into 3 predicted stages: At the first stage they speak mostly Russian with some high frequency insertion of words/phrases from Ukrainian. At the second stage, they use more Ukrainian and there is continued high frequency insertion Ukrainian in addition to full switching between Russian and Ukrainian. Finally, at the third stage, they use mostly Ukrainian, occasionally borrowing words/phrases from Russian. We looked at the those stages individually for each speaker and then noted the code-switches that they had. We categorized each switch as a word, phrase, sentence, or clause, and counted the number of each type as they occurred. We then noted the context of each switch for further analysis so that we could more easily discover any code-switching patterns present later on.

When observing code switching, we used the categories of phrases, sentences, words, and clauses to organize cases. Phrases refer to switches from one language to the other halfway through a sentence, sentences refer to complete thoughts in one language, words to certain isolated switches, and clauses to small sentences embedded within larger ones. The main categories of contexts for code-switches in our data that we found were common Ukrainian word insertion, when showing national pride, humor, a slip, incorrectly using a Russian word believing it’s Ukrainian, and switching when not knowing the translation.

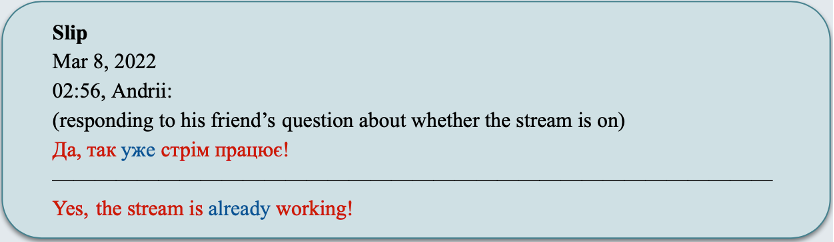

It’s clear to see these different kinds of contexts when looking at short examples such as in Figure 2. Here we can see that the speaker is inserting a Russian word into a Ukrainian sentence. Russian “уже” is a high-frequency word that closely resembles Ukrainian “вже”, so this is most likely a slip.

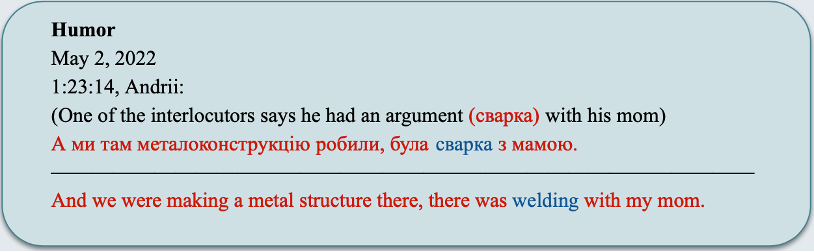

In the second example in Figure 3, we can see how wordplay is utilized. The word “сварка” means argument in Ukrainian and in Russian it means welding. One of the subjects said in Ukrainian that he had an argument (“сварка”) with his mom, and the speaker joked that they were making a metal structure with his mom, and thus there was “сварка”, meaning welding. Here we can see how the speaker used a word that exists in both languages but used it with Russian meaning for a comic effect.

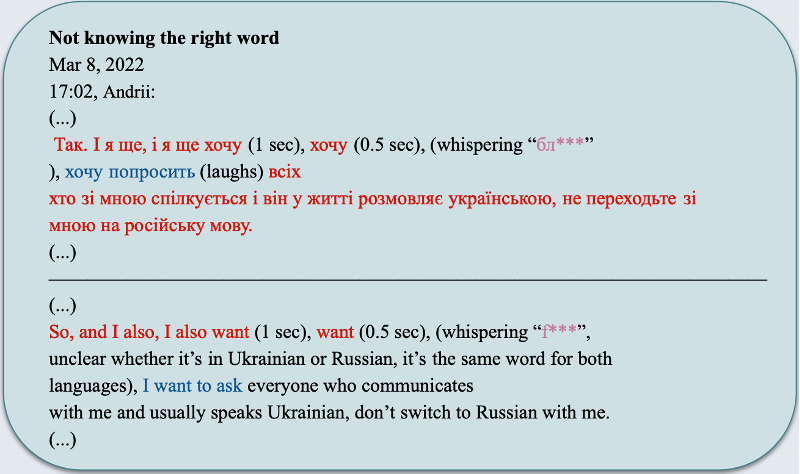

In Figure 4, the speaker was clearly struggling to recall the right word, so he inserted the phrase in Russian into a Ukrainian sentence.

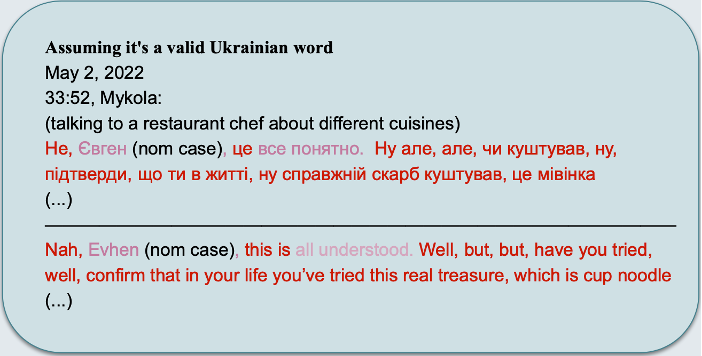

A clear example of the speakers assuming what they are saying is a correct word in Ukrainian can be seen in Figure 5.

The name of one of the speakers (Євген) is used in the nominative case, as it would be in Russian, whereas in Ukrainian, the vocative case (Євгене) should be used. “Bсе” is pronounced with a Ukrainian accent and is a hybrid of the Russian “всё” and the Ukrainian “усе”. The Russian word “понятно” is pronounced with a Ukrainian accent, and the speaker most likely assumes it to be a valid Ukrainian word. This seems to be a common pattern because we’ve seen several instances of it.

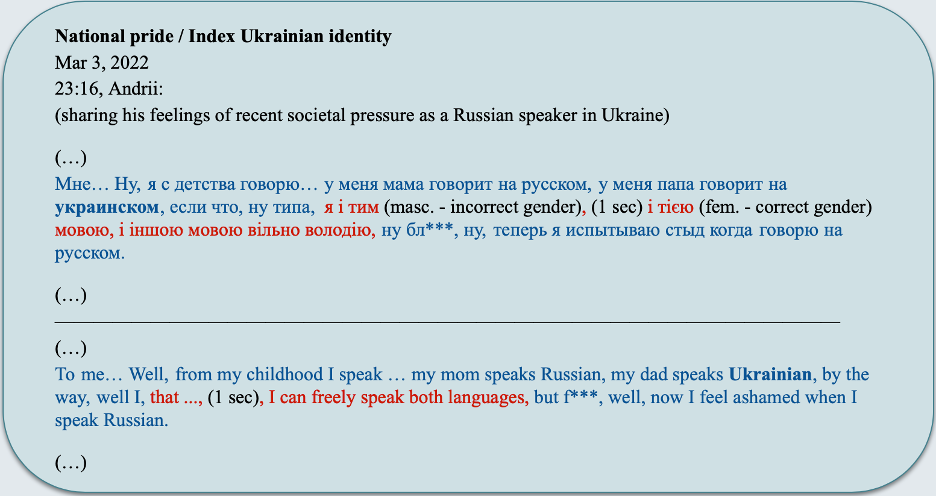

The speaker first uses masculine gender in Figure 6, because the Russian word for language “язык” is masculine, but then corrects himself and uses feminine gender, which is correct for the Ukrainian word “мова.” Also, you can see that he is inserting a clause in Ukrainian to prove that he has some proficiency in the language and show his Ukrainian identity.

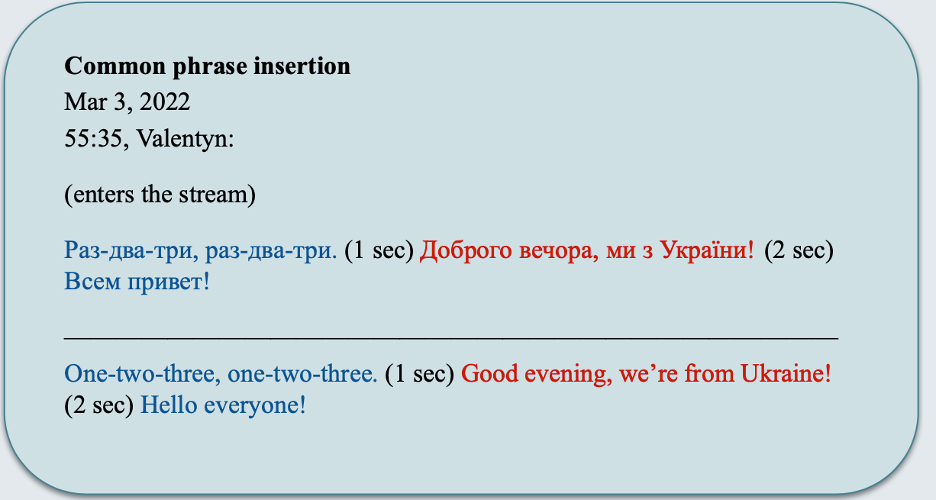

Lastly, in Figure 7, the speaker is saying a common Ukrainian phrase that has been used extensively and is embedded by 2 sentences in Russian.

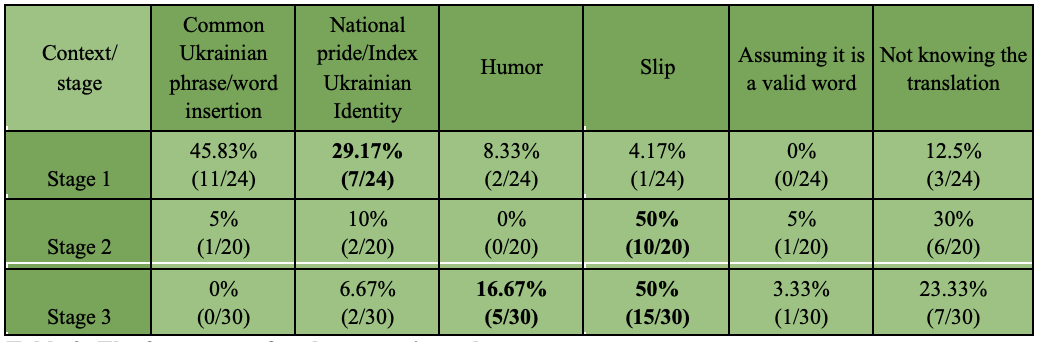

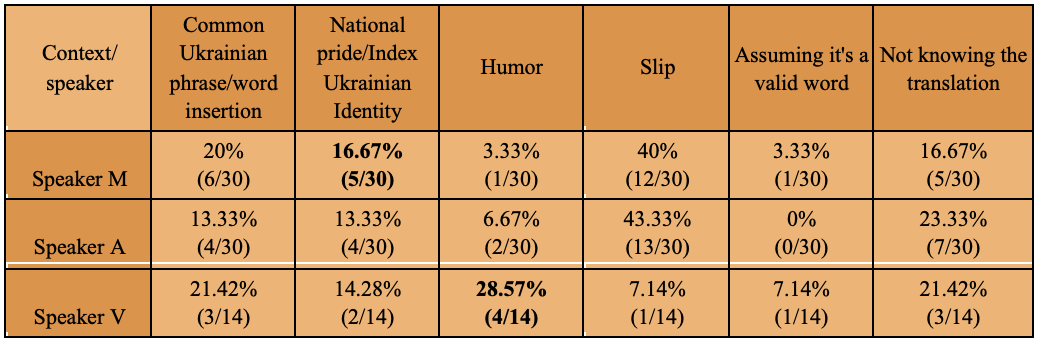

In cases of Ukrainian word insertion, speakers would add in phrases or words that are used regularly, such as greetings or slogans. Because of its fairly clear division amongst the stages in Table 1, we believe that the speakers first used phrases they were familiar and confident with as they began to transition as a way to clearly and immediately signal their solidarity and intent to distance themselves from Russian.

The speakers also used Ukrainian phrases and words to express national identity and pride. Similarly, to the case of common words and phrases, this behavior, as seen in Table 2, was utilized more in stage one than stages two and three to quickly and easily express their Ukrainian identity.

The use of this context eventually decreased, just like common words and phrases did, as the speakers grew more confident in Ukrainian and did not need to quickly express their pride, since speaking the language fluently accomplished the task. This use to express national identity was higher than we originally thought it would be, and it was somewhat surprising to see it happen so often.

Another pattern we observed was the use of code-switching in a humorous or comedic manner. This kind of code-switching is intentional and utilizes parts of both languages such as intonation and meaning to create a joke or a wordplay. However, the frequency of humor, shown in Table 2, was surprising, as we anticipated it to be far higher than it actually was in stage one. The use of humorous code-switching was present scarcely in stage one, not at all in stage two, and was most prominent in stage three.

Slips in our data involved a speaker starting a sentence in Ukrainian but accidentally reverting to Russian before they finished expressing their thought. In some cases, the speakers would realize they had slipped and correct themselves, but in others the speakers would continue, finishing the thought in Russian. Table 2 also shows that slips accounted for the majority of code-switches from stages two and three. This is likely due to the speakers using primarily Ukrainian for the second and third stages, so slips in the first stage are less common given that little Ukrainian is actually being used.

We were able to find recurring contexts related to speakers as well. As we previously mentioned, speakers would often code-switch at the start in order to index themselves as Ukrainians. The speakers did so relatively the same amount, but Speaker M did this slightly more than the other speakers, as shown in Table 3.

The use of humor however showed a greater disparity. Speaker V humorously code-switched to a far greater percentage than his counterparts. A better mastery and confidence of the language would likely allow the speakers to make more jokes and use differences between the two languages more effectively. We found that Speaker V seems to have the greatest ability of the three to speak Ukrainian. He demonstrated this by completely skipping stage two and barely needing any time to transition, so we believe that he was able to use the language more effectively to make jokes through his knowledge of both languages and their differences.

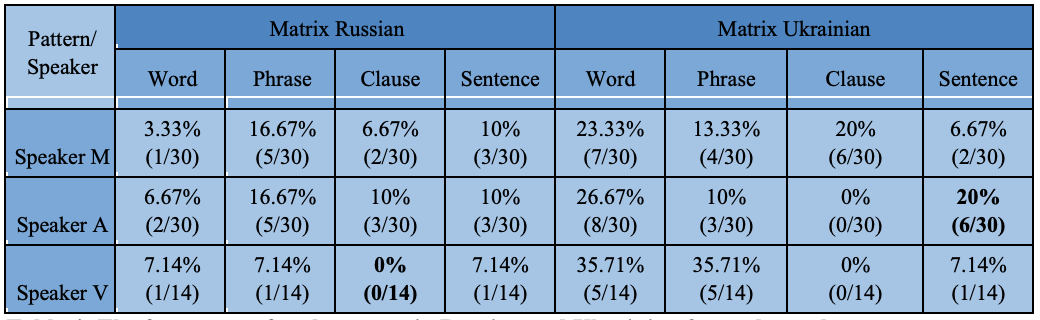

Since Speaker V displayed different code-switching patterns when compared with his counterparts and did less code-switching in general, he did not at any point use clause insertion when code-switching, as in Table 4, which showed more evidence as to his strength in the language. For Speaker A, we noticed that he code-switched more sentences than Speakers V and M, especially when switching from Ukrainian to Russian.

Looking further than these 3 subjects and this specific context, the data from our study may be a useful reference when looking at rapid language transition in other countries or perhaps what people tend to struggle with versus what they find easy when changing their primary language both in Ukraine and in other places. As this kind of research continues, we might be able to gain insight into how this rapid language transition could result in, or perhaps already has resulted in, new linguistic features such as an emerging accent or dialect and the creation of new words or slang from primarily Russian speakers becoming primarily Ukrainian speakers. If you are looking for additional information about the languages’ history and how they are being used in the ongoing war today, the following blog post, Ukrainian vs Russian: How Do These Languages Differ, is very useful.

References

Azhniuk, B. (2017). Ukrainian Language Legislation and the National Crisis. Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 35(1/4), pp. 311–329. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44983546

Gardner-Chloros, P. (2009). Code-switching. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Krishnan, S., Noor, N., and Rasmani, K. (2011). Analysis on Stages of Code-switching by Bilingual Educators: A Case Study. International Conference on Applied Sciences, Mathematics and Humanities 2011, pp. 475-481. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338357063_ANALYSIS_ON_STAGES_OF_CODE-SWITCHING_BY_BILINGUAL_EDUCATORS_A_CASE_STUDY

Mahootian, S. (2020). Bilingualism (Routledge Guides to Linguistics). London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Common and Uncommon Ground: Social and Structural Factors in Codeswitching. Language in Society, 22(4), pp. 475–503. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4168471

Rating Group. (2022, March 19). The Sixth National Poll: the Language Issue in Ukraine. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://ratinggroup.ua/en/research/ukraine/language_issue_in_ukraine_march_19th_2022.html

San, H. K. (2009). Chinese-English Code-switching in Blogs by Macao Young People (Publication No. 9877103) [Master’s thesis, The University of Edinburgh]. Edinburgh Research Archive.

State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. (2003-2004). All-Ukrainian population census 2001. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/