In our project, we investigated three linguistic variables – Disfluency/Stuttering, Figurative Language, and Introspection/Emotional Language – to explore their occurrence and patterns in speech, particularly under the influence of LSD. Disfluency manifests as disruptions or hesitations in speech, while stuttering involves involuntary sound repetition. Figurative language employs metaphors and analogies, and introspective/emotional language conveys inner thoughts and feelings. Through data analysis, we observed instances of disfluency, such as stuttering, unfinished sentences, and prolonged pauses, alongside examples of figurative language, like metaphoric expressions. Throughout the timeframe, introspective language emerged, reflecting individuals’ contemplation of existential questions and emotional experiences.

Our findings revealed a notable increase in all three linguistic variables among LSD-exposed individuals compared to controls. This heightened occurrence suggests a potential influence of LSD on speech patterns, with introspective and figurative language showing significant upticks. Notably, the use of introspective language during LSD exposure may hold implications for therapeutic practices, particularly in trauma-focused therapy and emotional exploration. Leveraging LSD’s capacity to facilitate uninhibited self-expression, therapists could effectively navigate sensitive topics and evoke relevant memories, potentially enhancing treatment outcomes for individuals struggling with emotional trauma.

The linguistic effects of LSD present promising avenues for advancing mental health research and therapeutic interventions. By harnessing the potential of psychedelics like LSD within therapeutic contexts, we may redefine approaches to trauma resolution and personal growth. With further exploration and integration of these findings into clinical practice, we anticipate transformative changes in mental health treatment paradigms, offering hope for individuals across diverse communities.

Introduction and Background

Can psychedelics really be used as a medical treatment? This is a question that has puzzled the minds of researchers since the late 1900s. It has been long known that LSD impacts cognitive function (Wießner et. al, 2023). As such, researchers were interested to see if LSD could impact language usage. One study has observed that people under the influence of LSD have increased usage of emotional language and metaphorical speech (Bryła, 2022). Additionally, another study has seen that there is an increase in disfluency and incoherent speech when people talk under the influence of LSD (Sanz et. al, 2021). Although there has been interest in using psychedelic drugs such as LSD as an alternative way to treat people with mental disorders, there has not been much research on how exactly LSD affects communication.

Our research aims to elucidate how LSD impacts communication by examining the patterns of speech of people under the influence of LSD and comparing it to the normal speech of people who are not under the influence of any psychedelics. We hypothesize that LSD will cause an increase in disfluency, such as disruptions stuttering, and figurative language use. Our research contributes to the psychedelic research field by studying specific linguistic variables that have not yet been studied in the context of LSD and other psychedelics. LSD is an illegal drug, making it difficult for researchers to legally obtain and study it under ethical conditions. It is important to fully understand the effects of LSD before using it as an approved medical treatment.

Methods

For our methods, all subjects in this project design are adults between the ages of 21 and 30 years old, and they all identify as frequent LSD users. Under the influence of LSD, we observed patterns of disfluency, stuttering, emotional/introspective language, and figurative language use. We gathered data from two primary sources. The first source was a public YouTube video titled, “Adam and Quentin’s ENTIRE Live Acid Trip | Bicycle Day Special”. The video was posted on April 21st, 2021, and went on for 5.5 hours. The participants in this video, Adam and Quentin, both spent the first 10 minutes of the video sober. We observed their speech patterns and behavior during this time as the control. After 10 minutes had passed, both took 250ug of LSD and felt the effects about 45 minutes later. Our second source consisted of 4 anonymous volunteers who took 150µg of LSD each. For the control, their sober speech and behavior were observed and recorded for about 30 minutes before taking the LSD. On average each volunteer felt the effects take hold about 1 hour after consumption and the effects wore off after about 4.5 hours. All 4 participants experienced this trip together and were recorded with oral and written consent. Due to confidentiality agreements as well as ethical and safety measures for our volunteers, their names were omitted from this project and the recording was converted into a transcript.

Results and Analysis

In our project, we studied three linguistic variables: Disfluency/Stuttering, Figurative Language, and Introspection/Emotional Language. Disfluency is discontinued speech or lowered quality and unfinished sentences. Stuttering is the involuntary repetition of sound. Figurative language is talking about one kind of thing, in terms of another. Introspection/Emotional language is speech conveying one’s inner thoughts and consciousness. Some quoted examples of disfluency from our data are: stuttering – “to-together?”, unfinished sentences – “I don’t know how, like…”, long pauses, and many “uhh”’s. Examples of figurative language from our data: “in the back of your head”, “in the back of your mind”, and “Like, as soon as our soul leaves our body, the vultures swoop in. Humans are basically, like, vultures, you know?”. Lastly, a few examples of introspective language from our data are: “What do you think is gonna happen when you die?”, and “Like I feel like, I believe in like, reincarnation a little bit…”.

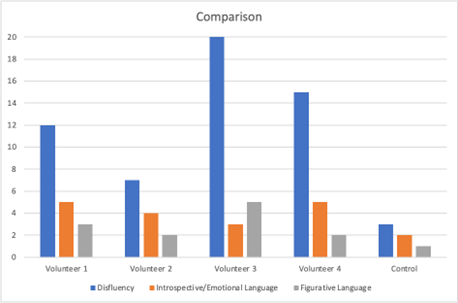

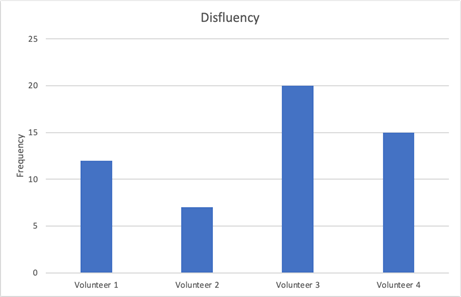

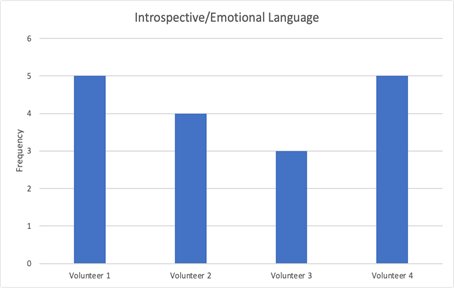

We can see from our results that disfluency had the highest frequency among all of our volunteers. The rate of disfluency was about 2-3 times more frequent than both figurative language and introspection, except for volunteer two, who had much less disfluency than the rest of the volunteers. Figurative language occurred the least, except for volunteer three. Though it only occurred slightly less than introspection/emotional language. Compared to our control data, all three of our variables were higher when participants had taken LSD. The most shocking difference was that of disfluency, which remains pretty low in our control data, and is extremely high (comparatively) in all of our volunteers once they had taken LSD.

Discussion and Conclusion

When beginning our research, we set out to find evidence that consumption of LSD had an impact on speech patterns. We assessed the variables of stuttering/disfluency, introspective/emotional speech, and the use of figurative language; across all modalities of our data collection, we found that there was an increased occurrence of all three variables.

One particularly important implication of this research is related to the subjects’ increase in the use of introspective and figurative language when under the influence of LSD. With the growing field of psychedelic-assisted therapy projected to double its global market value in the next four years, we believe it is important to steer this research in the direction of enhancing current protocols for talk therapy. LSD’s ability to invoke upon the user an uninhibited, vocalized train of thought, with a particular emphasis on sharing emotional memories, could prove to be extremely useful in therapeutic settings where there are feelings of shame around discussing certain events. Therapists who center their treatment on trauma-resolution and shifting a patient’s overall perspective on life may find LSD useful for broaching sensitive topics and eliciting relevant memories.

The linguistic effects of LSD demonstrate great potential for reimagining the scope of mental health research and how to treat individuals for which traditional therapeutic interventions have not been successful. We believe that, with further research into this field, large-scale changes can be implemented that will impact the lives of individuals across many different communities.

References

Bryła, M. (2022). What Conceptual Metaphors Appear in Texts on Psychedelics and Medicine? Corpus-Based Cognitive Study. Respectus Philologicus, 42(47), 154-166. https://doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2022.42.47.115

Krebs, T. S., & Johansen, P.-Ø. (2013). Over 30 million psychedelic users in the United States. F1000Research, 2, 98. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.2-98.v1

Sanz, C., Pallavicini, C., Carrillo, F., Zamberlan, F., Sigman, M., Mota, N., Copelli, M., Ribeiro, S., Nutt, D., Carhart-Harris, R., & Tagliazucchi, E. (2021). The entropic tongue: Disorganization of natural language under LSD. Consciousness and Cognition, 87, 103070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2020.103070

Wießner, I., Falchi, M., Daldegan-Bueno, D., Palhano-Fontes, F., Olivieri, R., Feilding, A., B. Araujo, D., Ribeiro, S., Bezerra Mota, N., & Tófoli, L. F. (2023). LSD and language: Decreased structural connectivity, increased semantic similarity, changed vocabulary in healthy individuals. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 68, 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.12.013