Cc: Kyna Horten, Phoebe Morales, Lukas Weinbach

What if I told you that the way you write your emails is a dead giveaway of your gender identity? What if I told you there is a way to make this less obvious? If you want to learn more about Gendered Language, keep reading! What we know so far: Research parses variations in speech into ‘powerful’ language and ‘powerless’ language, or ‘men’s language’ and ‘women’s language. ‘What research has not considered yet: For centuries, men and women have had gender roles to perform which influence their speech behaviors; however, there is no social gender for people outside of the binary to perform, perhaps as a result of the idea that biological sex runs on a binary (which it doesn’t). In recent years, the options for social gender are changing from a binary to include those outside the traditional man/woman dynamic. Bathrooms, passports, and titles (mrs./ms., mr., mx.) are beginning to accommodate genders outside of the binary. Still, there are no set stereotypes, roles, or expectations for genderless people. We wanted to investigate how individuals identifying as agender perform language when writing emails.

For our study, we chose a convenience sample of three participants. The target demographic were nonbinary English-speakers in the Millennial/Gen Z age-range. One participant was assigned-female-at-birth and part of the cisgender control group. The other two participants were agender, and this group was a mix of assigned-female-at-birth and assigned-male-at-birth. Each participant provided at least six formal email threads for analysis. At least three of these were addressed to male recipients while the other half were addressed to female recipients. All recipients held a position of power over the participants. Before examining the emails, we produced a codebook full of key words and markers which signify powerless language. Here are a few examples of markers we coded:

| Code | Description of code |

| HEDGING (HD) | [sort of, kind of, I guess, it seems] |

| ITALICS (IT) | [so, very, totally, quite, really, !] Emphasis. |

| QUESTION INTONATION (QI) | question intonation in declarative context

[I was wondering if… ?] |

| THANK (TY) | [thanks, thank you] expressing gratitude |

| PLEASE (PLS) | [please] |

| APOLOGY (SRY) | [sorry] |

| EMBEDDING (EB) | [hope, wanted, wondering] |

| EMOTES (EMO) | emojis, emoticons [haha, lol] |

| ACCOUNTABILITY (ACC) | taking responsibility for a certain outcome, admitting fault |

| APPEASING (APP)

|

[hope you’re well] making social small talk to prepare for request; elevating recipient or denigrating oneself to appease them. |

We tallied these codes to calculate the average frequency of powerless markers for every X amount of words in each message.

Gerard Van Herk’s What is Sociolinguistics? (2017) provides concepts of gender identity, performance, and practice. Herk asserts that “in cross-gender interactions we can expect to see the greatest gender effect,” therefore, we analyzed cross-gender interactions to help gauge the effect of perceived gender.

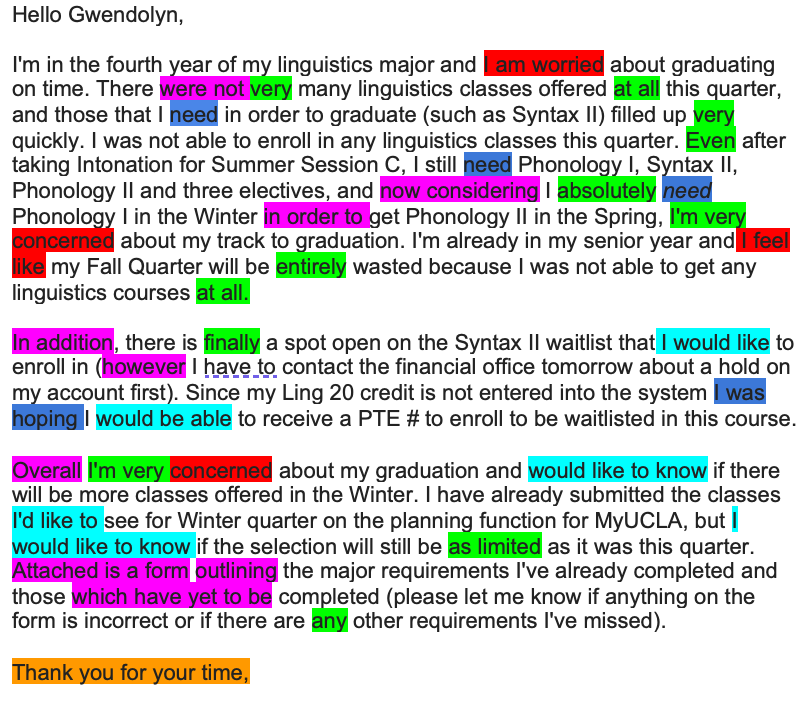

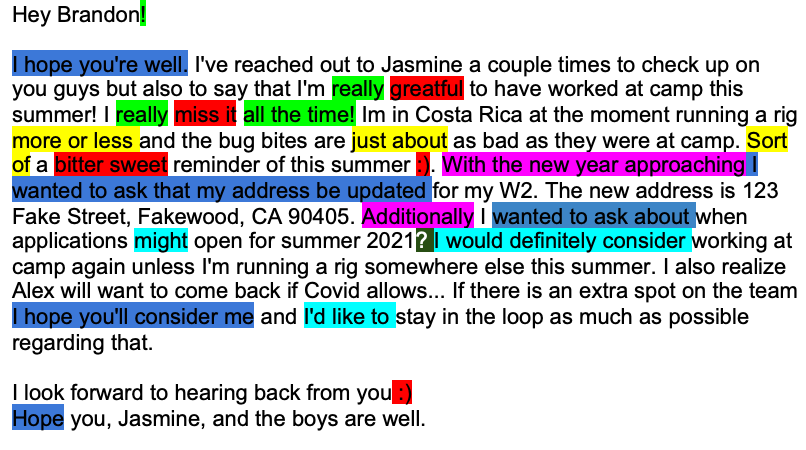

All data were coded twice, once by each of the researchers who did not compose said text. After coding was completed, we compared our findings in order to determine percent agreement of coding and in order to confirm that our coding system is well-defined and useful. Below are some example emails which we coded and analyzed as part of our data pool. The first is written by our assigned-female cisgender participant addressed to a female recipient, and the second is written by our assigned-male agender participant addressed to a male recipient. All names and sensitive information have been anonymized.

We found in our results that there is a notable increase in powerless markers in cross-gender interactions, according to assigned gender at birth. Below is a table summarizing the average frequency of powerless language towards female and male recipients for each participant:

| ANONYMIZED NAMES | AMANDA

(AGENDER, AFAB) |

DAPHNE

(CIS, AFAB) |

ERIK

(AGENDER, AMAB) |

| FEMALE RECIPIENT | 31.7 | 14.1 | 10.4 |

| MALE RECIPIENT | 11.8 | 11.2 | 13.4 |

We can see that gender identity had little, if any, effect on speech in emails. Regardless of identity, cross-gender interactions according to assigned gender at birth still produced more exaggerated use of powerless language, just as Van Herk predicted. As researchers, we expected that our agender participants, Amanda and Erik, would not conform to binary patterns. We predicted that their average frequency of powerless markers per message would be roughly the same across differently gendered recipients. Instead, our actual results imply that binary socialization, upbringing, and external perception impact the way that nonbinary people navigate the world. These results have many practical applications for the LGBTQ+ community. Some nonbinary people may be okay with presenting in a way that aligns with their assigned gender at birth; however, others may desire to present a different image. Perhaps agender and other nonbinary individuals can use this research to consciously move towards less gendered speech, if they so desire. Furthermore, individuals wishing to present as more masculine or more feminine may also use this research to alter their speech so that it better aligns with their identity.

However, it is also important to note that these cross-gender disparities are potentially social constructs. Powerless language is not inherently feminine or masculine, but we associate these qualities with gender performativity.

If a person is in a position of less power, they are inclined to use more polite language. This is not necessarily powerless language in itself. In fact, it can be powerful language in its own right, as the speaker or writer implements manipulative tactics in request-making. For those in a lower position, polite language is more likely to produce results.

There are several interesting topics for further research. As mentioned above, upbringing may have a significant impact on cross-gender language. Patriarchal, matriarchal, and neutral households may produce differing attitudes towards the power dynamic of men and women. So, depending on a person’s upbringing, they may use either more or less powerless language when speaking to different genders.

The sociolinguistic study of gendered language is said to have started with Lakoff’s early studies and eventually his book “Language and Woman’s Place” (1975). Since then, the study of language and gender has developed greatly. Lakoff’s Research has been referenced and expanded upon many times, but generally focuses on a binary view of gender, and non-binary topics are under researched fields of study. Although both gender identities and social genders outside of the binary have always existed, the term ‘agender,’ “denoting or relating to a person who does not identify themselves [sic] as having a particular gender” (Google Definitions), was first coined on the internet in the year 2000 (Them). Our own research is extremely limited, examining a small pool of data from a convenience sample of three participants, only two of which are agender. We did not study other nonbinary identities outside of agender, nor did we study binary transgender people. Further research may reveal more patterns or nuances which escaped our own research.

References

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (2007). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. In Politeness: Some universals in language usage (pp. 61-83). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Cameron, D. (2010). Performing Gender Identity Young Men’s Talk and the Construction of Heterosexual Masculinity. In 1367818629 1000231388 D. Kulick (Author), Language and sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511791178

Herk, V. G. (2018). What is sociolinguistics? In What is sociolinguistics? (pp. 86-100). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Myers, Kristen. (2012). Cowboy Up!. ResearchGate. www.researchgate.net/publication/276215982_Cowboy_Up.

O’Barr, William M., and Bowman K. Atkins. ‘Women’s Language’ or ‘Powerless Language’? Women and Language in Literature and Society, by Sally McConnel-Ginet (1980). New York: Praeger, pp. 93–110.

Silverstein, M. (1976). Shifters, Linguistic Categories, and Cultural Description. In 1367858396 1000257581 K. H. Basso & 1367858397 1000257581 H. A. Selby (Authors), Meaning in anthropology (pp. 11-55).

Them. (2018). What Does It Mean to Be Agender? Them., Them. www.them.us/story/inqueery-agender.