Alexander Gonzalez, Maeneka Grewal, Nico Hy, Zoe Perrin, Vivian San Gabriel

The relevance of gender-neutral language has surged due to growing acceptance towards nonbinary and gender non-conforming people as well as the dissolution of the gender binary. Through comparative analysis of native English and Spanish speakers, we investigated the impact of grammatical gender on the methods speakers employ to express gender neutrality. Since Spanish sentences require full gender and number agreement, expressing gender neutrality in Spanish presents more challenges than in English. We asked participants to describe images of individuals and observed that the English speakers used gender-neutral language at higher rates than the Spanish speakers did. Their methods differed as well. Spanish speakers were more likely to mix feminine or masculine forms, alongside neutral descriptions, which we interpreted as attempts to use gender-neutral language. We can infer that even when Spanish speakers are looking to express something gender-neutrally, they may be limited by the lack of gender-neutral lexical items that can be used throughout an entire utterance. Our experiment was limited to written responses and as a result may not be representative of these speakers’ language use overall. More experiments dealing with oral speech and analyses of other gendered languages would contribute to the knowledge and understanding of this field.

Introduction

The language of gender inclusivity is constantly shifting and becomes increasingly relevant as our understanding of gender changes and the voices of nonbinary individuals are amplified. The recent surge in nonbinary visibility has drawn attention to the grammar of gender-neutral pronouns, especially in languages that have grammatical gender marking. We wanted to explore how speakers navigate using gender identity-related pronouns and terms to express gender neutrality, particularly in English, a language that does not use grammatical gender, and Spanish, a language that does use grammatical gender.

In English, the pronoun “they” is often used as a gender-neutral pronoun. The Spanish equivalent would be the novel pronoun “elle/ellx.” However, Spanish’s grammatical gender makes this pronoun difficult to use in spontaneous speech. In Spanish, all nouns and everything associated with them must be modified to fit gender and number agreement, while in English, nothing needs to be modified in order to use “they” in a sentence.

Through this experiment, we were looking to explore how grammatical gender may impact the ways speakers’ expresses gender neutrality when referring to a subject. This experiment focused specifically on individuals’ use of pronouns and other gender markers in their writing. We collected responses from native English and Spanish speakers of varying gender identities, looking to highlight the different ways gender neutrality is encoded in languages with grammatical gender compared to languages without it. As English already possesses a gender-neutral pronoun and does not use gender agreement, we predicted that English speakers will be more likely to use gender-neutral terms than Spanish speakers.

Methods

To test out this hypothesis, we conducted an experiment using Google Forms surveys to track the usage of pronouns and gender marked words in English and Spanish written communication. We collected our data through 2 separate surveys, each written in English and Spanish respectively. Each survey contained the same 10 computer generated images of androgynous individuals paired with a prompt requesting that participants describe the individuals using full sentences. It was important for us to disclose that the individuals in the photos were computer generated so as to avoid participants manipulating answers due to fears of misgendering real people. It was also important that we asked participants to describe the people in full sentences to increase the likelihood of participants using pronouns and gender marked terms.

The methodology used in this experiment was inspired by a prior study done by Bradley, Salkind, Moore & Teitsort (2019) which examines English L1 cisgender subjects’ perception of singular “they” as a non-gendered pronoun. In this study, the researchers analyzed English recordings of participants’ verbal reactions to image stimuli. However, our experiment will be analyzing how gender neutrality is expressed in writing for both English and Spanish. We chose to analyze written communication because of possible difficulties in verbally expressing gender neutrality in Spanish due to the language’s grammatical gender. It was found in the study by Slemp (2020) that verbally expressing gender neutrality in Spanish takes conscious effort. This is not only because of Spanish’s grammatical gender agreement, but also because there is no verbal standard gender neutral morpheme. Slemp found that, in order to express gender neutrality, participants alternated between the morphemes -e and -x in written language as replacements for -a and -o. These findings guided our decision to analyze written language as opposed to verbal responses.

Results

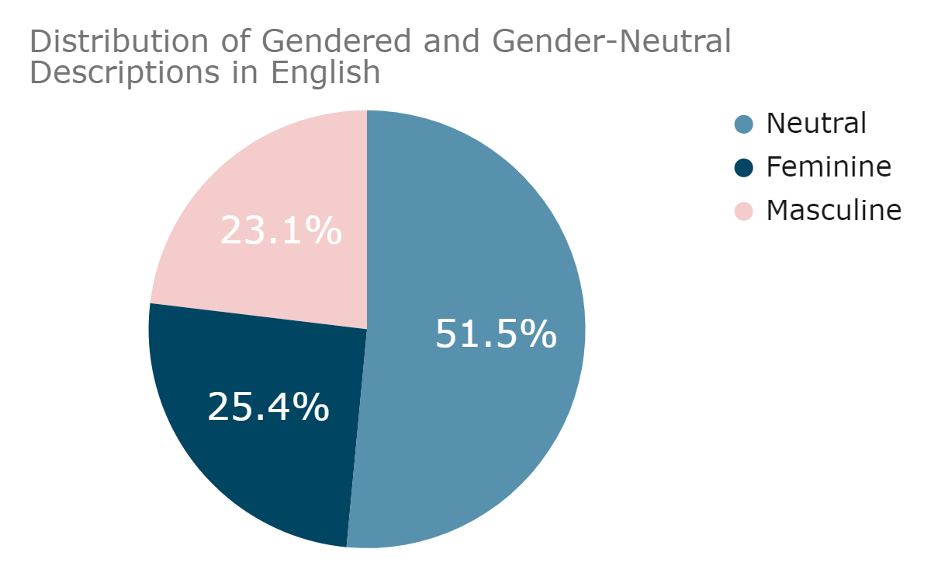

We received 13 responses to our English survey, and since each responder was asked to describe 10 images, we received a total of 130 descriptions in English. We found that 51.5% of these descriptions used gender-neutral language. Examples of gender-neutral language found in our English speakers include the explicit use of the gender-neutral pronoun “they” in sentences like “they have dark colored eyes with crow’s feet,” as well as the total avoidance of pronouns in favor of gender-neutral terms like “person” in sentences like “this person has dimples.”

The remaining 48.5% of descriptions used gendered language, with 25.4% of the responses being feminine descriptions and 23.1% being masculine descriptions. Of our 13 responders, 10 people (76.9%) used a neutral description at least once, while 3 people (23.1%) did not use a neutral description at all, meaning that they gendered every single image.

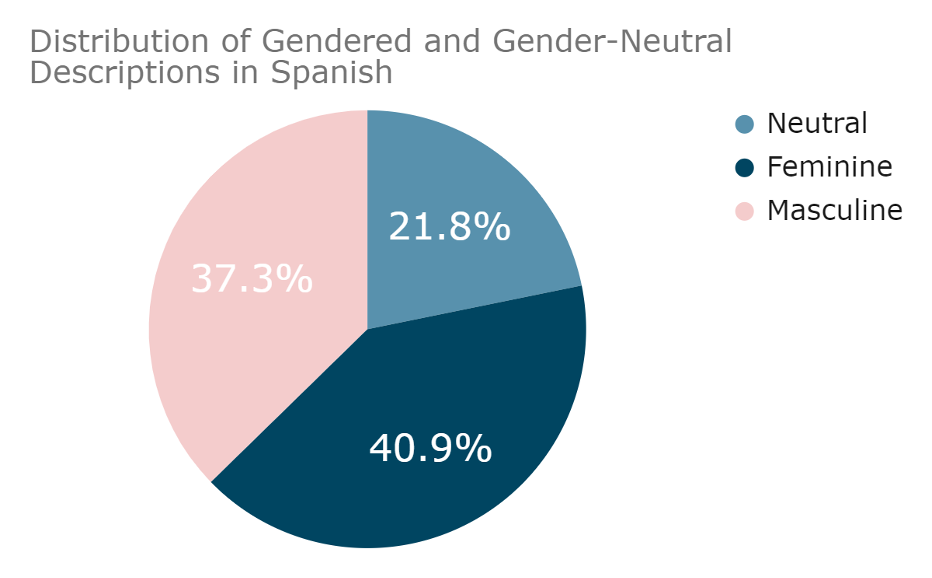

We received 11 responses to our Spanish survey for a total of 110 descriptions. While the use of gender-neutral language was a majority in the English survey, only 21.8% of the Spanish descriptions used gender-neutral language, and 5 of these gender-neutral responses used feminine or masculine pronouns or adjectives combined with neutral descriptions. We interpreted these responses as attempts to use gender-neutral language. Other ways in which Spanish speakers expressed gender neutrality include the avoidance of pronouns similar to the avoidance practiced by English speakers, the use of question marks to signal uncertainty about gender, as in “el señor?” and the use of a dual marker “-o/a” for gender-neutral adjectives.

Within the remaining 78.2% of gendered descriptions, 40.9% were feminine and 37.3% were masculine. Of our 11 responders, 7 people (63.6%) used a neutral description at least once, while 4 people (36.4%) did not use neutral descriptions at all.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our results show that our English-speaking participants used more gender-neutral language than our Spanish-speaking participants. We can most likely attribute this to the fact that using the pronoun “they” was the most common way English speakers chose to convey gender neutrality: as we hypothesized, it appears that the availability of the gender-neutral “they” is what allowed them to do so. Gender-neutral language also seems to be more easily accessible in English, as shown in the way some of the English speakers fluidly switched between the pronouns “he,” “she,” and “they,” both between and within sentences.

On the other hand, none of the Spanish speakers used the novel pronouns “elle/ellx,” which suggests that these pronouns are less widely accepted and less readily available than the English “they.” This highlights an obstacle to introducing a new pronoun into a language: it is not likely to be understood and used in casual language if it is not well-known by speakers. It is most likely because the Spanish speakers didn’t have this gender-neutral pronoun available that they used various other methods to convey gender neutrality, such as mixing the gender agreements of articles, adjectives, and nouns. Mixing masculine and feminine forms suggests that they were aiming to construct gender-neutral sentences using the resources available to them.

In both languages, there were speakers who avoided pronouns altogether and used the word “person” or “individual” instead of gendered terms like “man” or “woman.” Some speakers expressed uncertainty over their use of gendered language as well as the gender of the person in the image, either explicitly through words like “I think,” or implicitly through the use of question marks. These uncertainties suggest that participants would have been more confident if there were more gender-neutral options in circulation—not only existent, but well-known and commonly used, as to allow a mutual understanding of the word between both speaker and listener.

While our data was collected in the form of written responses and may not accurately reflect the use of gender-neutral language in English and Spanish speakers, especially because written language lacks the spontaneity of spoken language, our results suggest that English speakers use gender-neutral language at a higher rate than Spanish speakers do. We think it would be worthwhile to conduct a similar study with a focus on speech rather than writing, as it would not only allow more insight into the use of gender-neutral language in general, but also investigate the feasibility of introducing new phonemes into languages for the sake of gender inclusivity, such as the -x marker in “ellx.” Ultimately, though, we have reached a better understanding of the various ways speakers can incorporate gender-inclusive language in their casual speech.

Bibliography

Balhorn, M. (2004). The Rise of Epicene They. Journal of English Linguistics, 32(2), 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424204265824

Bradley, E. D., Salkind, J., Moore, A., & Teitsort, S. (2019). Singular ‘they’and novel pronouns: gender-neutral, nonbinary, or both?. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America, 4(1), 36-1. https://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/PLSA/article/viewFile/4542/4148

Lew-Williams, C., & Fernald, A. (2007). Young children learning Spanish make rapid use of grammatical gender in spoken word recognition. Psychological science, 18(3), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01871.x

Schriefers, H., & Jescheniak, J. (1999). Representation and Processing of Grammatical Gender in Language Production: A Review. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 28, 575-600.

Slemp, K. (2020). Latino, Latina, Latin@, Latine, and Latinx: Gender Inclusive Oral Expression in Spanish.