Hyung Joon (Joe) Kim, Mocha Ito, Irene Han, Sena Ji, Luis Flores

Our study tests the validity of the Myers-Scotton’s (1993) Matrix Language Frame (MLF) hypothesis in light of modern Japanese-English and Korean-English bilingual speakers’ code-switching data (Myers-Scotton & Jake, 2009). Code-switching (CS) is the umbrella term for the use of more than one code, such as languages, dialects, sub-dialects, and accent, within or across conversations. Our focus is on two sub-elements of intra-sentential CS: alternation and insertion. We test the hypothesis by looking at whether the Morpheme Order Principle and the System Morpheme Principle hold true in our transcribed data of a total of 5 bilingual participants’ conversations in two separate groups. Our analysis reveals three new insights, which show that the two principles of the MLF hypothesis can be overriden under certain linguistic restrictions and in specific psycho-social context, as well as the fact that the frequency of alternation is positively correlated with the bilingual speaker’s proficiency in his or her first language.

Introduction/ Background

The study of bilingual code switching began in the 1900s. However, the way how East-Asian descent Americans code switch in their conversations with another bilingual interlocutor is an area that has not been addressed as much by modern linguistic scholars, despite the consistent increase in the population of East Asian-American bilingual speakers in the last few decades. It is estimated that approximately 14.1 million Asians have immigrated to the US since the 1850s (Migration Information Source, 2020). The obtaining of a second language by the 1.5 or 2nd generation immigrants in America has led to a number of intra-racial cultural issues. For example, the rapid code-switching that 1.5 or 2nd generation bilingual children often use has led to intra-cultural division between the 1st generation immigrant parents and their children. This is because the parents are often more used to conversing in their mother tongue Asian language, whereas the 1.5 and 2nd generation children are used to mixing more than two languages in their speech.

In fact, there is a sizable void in the existing literature in the field of Asian-American bilingual code-switching. Linguists have undertaken studies on code switching with rarer and more exotic pairs of languages, such as Lingala-Swahili (Bokamba, 1988) and Turkish-Dutch (Backus, 1992), but not as extensively on East Asian language-English pairs. Our study aims to fill the void in the study of bilingualism by focusing on how bilingual speakers of East Asian language and English converse with their bilingual family members. We focus our analysis on insertion and Alternation. Insertion is using one primary language that forms the main grammatical frame, but inserting words from the second language into the sentence. Alternation is the back-and-forth switching between one language and another, involving a full switch to a different languages’ grammatical frame. We hope that our empirical research assists in bridging the generational disparity between the 1st generation and 1.5/2nd generation Asian American immigrants.

Our study tests the validity of the MLF Hypothesis. The hypothesis proposes two principles: The Morpheme Order Principle and the System Morpheme Principle. These principles are distinguished by Myers-Scotton’s terminology, known as the content morphemes and system morphemes. Content morphemes are words like nouns, verbs, adjectives that express semantic meanings and assign or receive thematic roles (they are structured into grammar by system morphemes). Their counterpart, system morphemes are functional words (words that have little meaning but express grammatical relations. i.e. propositions, articles, conjunctions, etc) that express the relation between content morphemes and do not assign or receive thematic roles (i.e. roles of noun phrases).

The Morpheme Order Principle states that in a sentence with mixed constituents from the Matrix Language (first language) and Embedded Language (second language), the surface morpheme order must not violate that of the Matrix Language (ML).

The System Morpheme Principle states that in a sentence with mixed constituents from the ML and EL, all system morphemes which have grammatical relations external to their head constituent must come from the ML.

In short, we propose the three following hypotheses:

First, EL system morphemes can have grammatical relations external to their heads. This overrides the System Morpheme Principle. We provide support by showcasing an example of EL system morphemes in our Japanese-English data.

Second, in a bilingual speaker’s speech with mixed constituents from ML + EL, the surface morpheme order constructed by the ML can be violated. The second finding overrides the Morpheme Order Principle. We show that there can be a disruption of an ML surface morpheme order in a sentence with ML + EL constituents in our Korean-English data.

Third, bilingual speakers that are more proficient in their first language engage in higher average frequency and longer total duration of alternation.

Methods

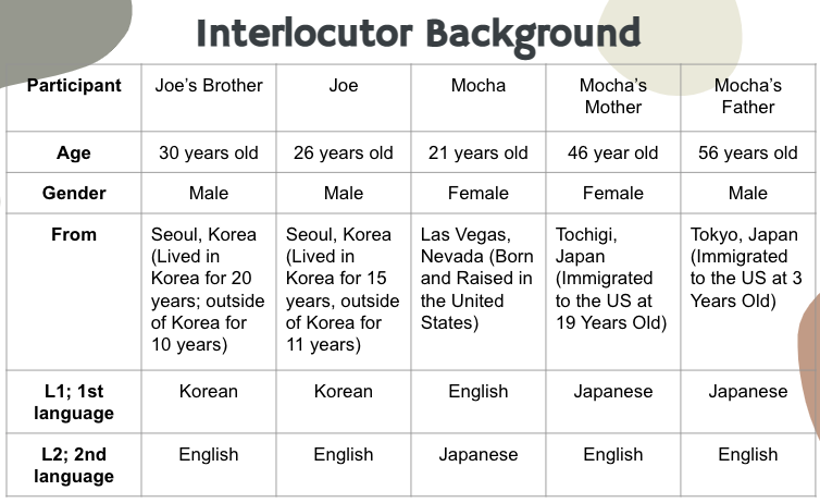

Table 1 shows the background information about the five bilingual speakers that took part in our research. Two were Korean-English bilingual speakers and three were Japanese-English bilingual speakers. All three Japanese-English bilingual speakers were fluent in both languages. The two Japanese parents’ first language was Japanese and their second language was English. Mocha’s first language was English, and her second language was Japanese. For the Korean-English bilingual speakers, both interlocutors were native speakers of Korean. Their first language (ML) was Korean, and their second language (EL) was English. The two Korean participants spent the majority of their lives (20 years and 15 years respectively) living in Korea than outside of Korea.

The Japanese student (Mocha) recorded 20 minutes of conversation with two of her parents and the Korean student (Joe) recorded 18 minutes of conversation with his older brother. Both students listened to the recording and transcribed the conversations with their family member(s). The sections spoken in a non-English language were translated into English.

After transcribing, we broke down our insertion data in order to examine the first two following aspects: the possibility of EL system morphemes that have grammatical relations external to their heads, and the violation of ML surface morpheme order of a sentence with ML+EL constituents. These findings would invalidate the System Morpheme Principle, and the Morpheme Order Principle, respectively. Third, we examined the total duration of alternation (in seconds), as well as the average frequency of alternation (per second), to assess the correlation between the tendency to engage in alternation and the proficiency in the speaker’s first language or second language.

Results/Analysis

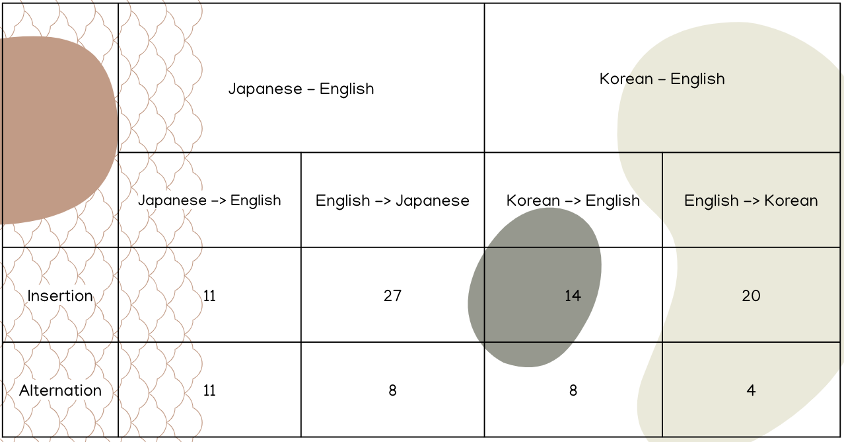

First, we counted the total number of times alternation and insertion appeared in each language pair.

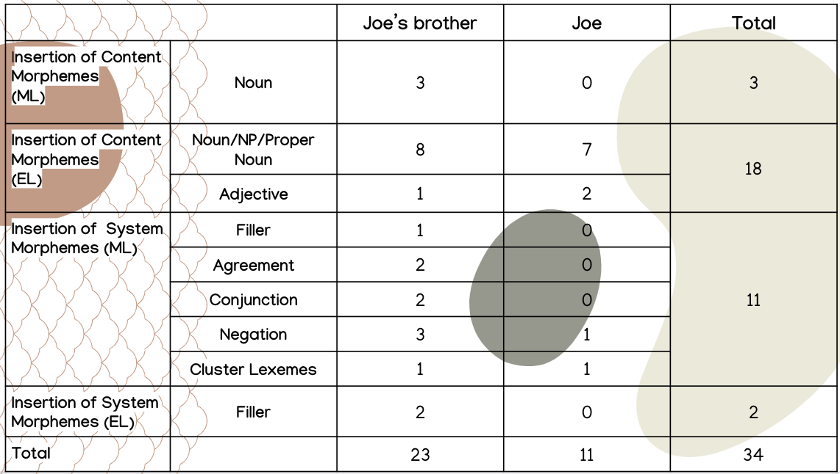

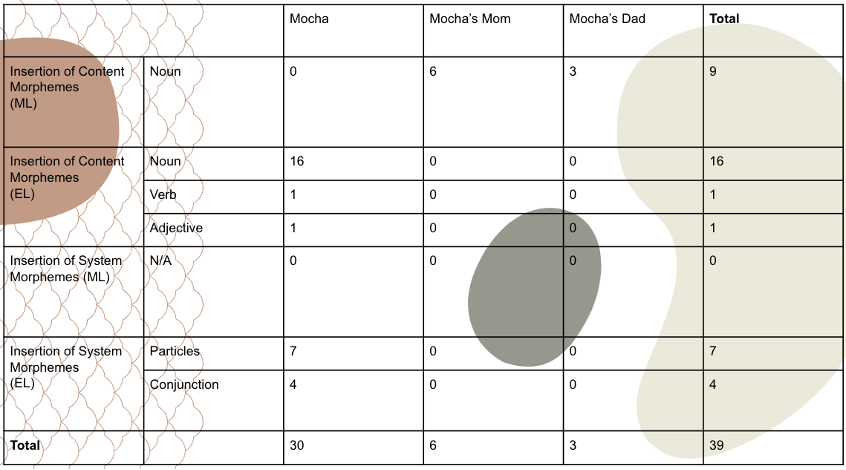

After counting, we categorized the inserted words into content and system morphemes. We observed if content and system morphemes are present in both ML and EL for the Japanese-English and Korean-English conversations.

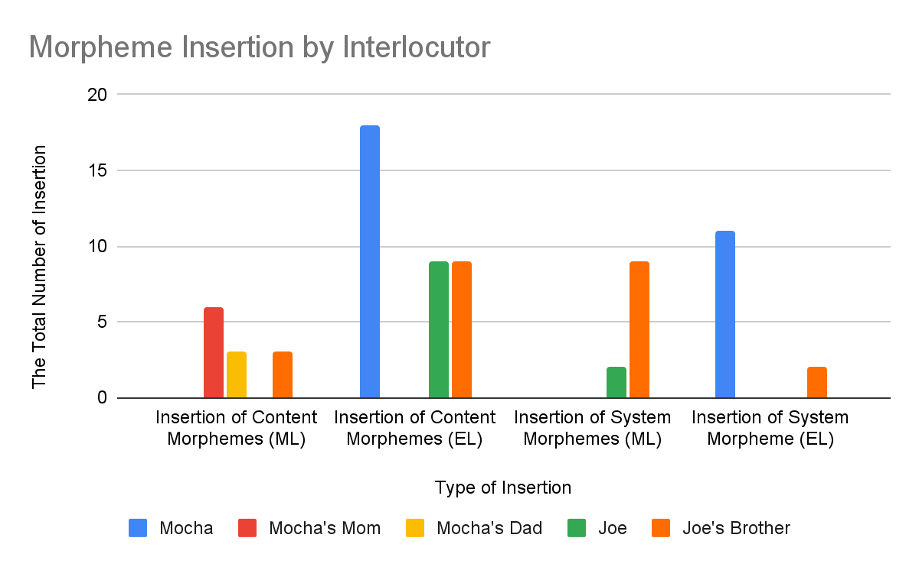

In Table 3, morphemes like nouns, negation, adjectives, and fillers appeared the most In the Korean-English data. In Table 4, nouns, particles and conjunctions appeared the most in the Japanese-English data. A bar chart in Figure 1 is based on Tables 3 and 4 summarizes morpheme insertion by interlocutor.

With this visual representation of the distribution of morpheme insertions, we were ready to test the System Morpheme Principle, which states that in a sentence with mixed elements of ML + EL, all system morphemes with grammatical relations external to their heads have to come from ML. Clearly, we could see that Mocha and Joe’s brother inserted system morpheme in EL. To invalidate this principle, we first had to confirm that the system morphemes in our data have grammatical relations external to their heads; then, prove that those system morphemes are from the EL, thereby negating the logic that all system morphemes must come from ML.

Excerpt 1. Example of EL system morpheme in Japanese-English data.

M: Mocha

Y: Mocha’s mother

Mocha’s EL system morphemes: no (の), kara (から)

M: Linguisticsのrequisiteほとんど終わってるから。

Linguistics no requisite hotondo owatteru kara.

M: たぶんだけどESLだと思うよ

for most [of] finished already.

M: Tabun ESL dato omou yo

Probably that [I] think

(I already finished most of the prerequisites for linguistics. I think it’s probably ESL)

Y:良かったね。でもMastersわどうするの?

(That’s good for you. But what are you going to do about Masters?)

In the excerpt above, Mocha, whose EL is Japanese, is inserting Japanese system morphemes, no and kara into the sentence. Words like no の is a system morpheme, because it is a functional word with little content meaning similar to a preposition. But no (の) bears grammatical relations with the latter EL system morphemes, owatteru kara (終わってるから). This a grammatical relationship external to the head of no (の), which is ‘Linguistics’.

Therefore, Mocha’s conversation with her mother clearly indicates the possibility of an EL system morpheme that bears an external relationship to its head, overriding the System Morpheme Principle.

Next, we went on to test the Morpheme Order Principle.

Excerpt 2. A sentence with ML+EL constituents with violated ML surface morpheme order.

J: Joe

D: Joe’s Brother

J: 그래도, 이제, 좀, free 하게 다니거나 그럴 수가 없지

Geraedo,eejae,jom, ha-gae daniguna geurul sooga up-jee

(But, now, a little, we can’t roam around freely)

D: New York 은 이미, it’s poppin’

eun ee-mi,

(New York is already, it’s poppin’)

In Excerpt 2, Joe’s brother uses the English NP “New York” to begin the sentence, which is followed by a Korean particle eun (은) and adverb ee-mi (이미), which means ‘already’. According to the Korean surface morpheme order, the morpheme that must always follow a Korean adverb has to be either a verb or an adjective attached to a past-tense inflection suffix, such as neut-eut-uh (늦었어), which is an adjective + past tense inflection suffix, such as:

neut-da (늦다) + –eut-uh (-었어)

Adjective stem + past tense inflection suffix

However, in our raw data, we see that the adverb ee-mi (이미), is followed by the English possessive determiner, “it’s”, which violates the ML (Korean) surface morpheme order of a sentence with ML+EL mixed constituents. Therefore, the example in our Korean-English bilingual conversation invalidates Myers-Scotton’s Surface Morpheme Order Principle.

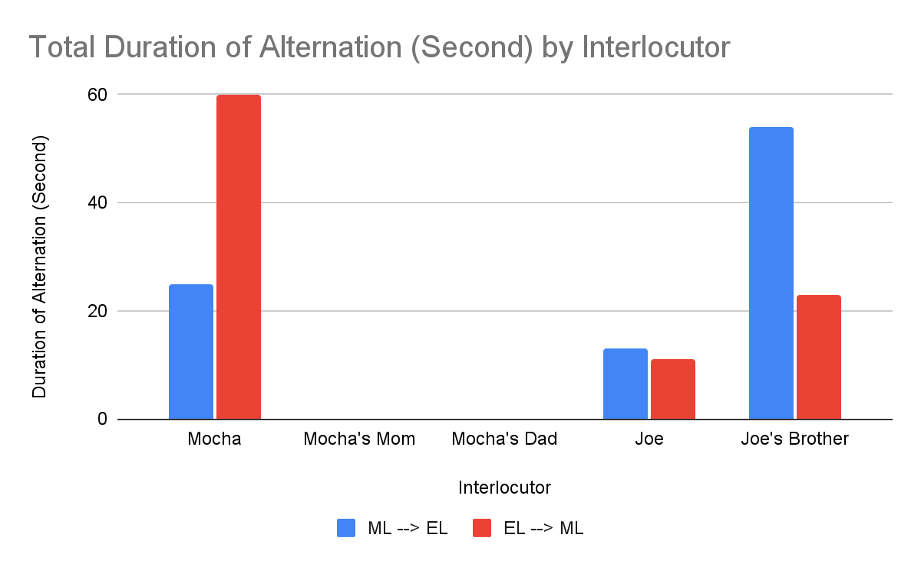

Lastly, we analyzed our alternation data by calculating the total duration (s) of alternation between ML and EL.

In Table 2, duration is the total length of alternated sentences (in seconds), including from the beginning of a sentence in language A to the end of the sentence in language B after the end of alternation. For example,

D: 호원 예술대, 재즈 피아노. Supposedly it’s one of the top three

Howon-Yesooldae, Jazz Piano

(Ho Won Music School, B.S. in Jazz Piano)

The entire sentence above was counted as one case of alternation, lasting between 5~10 seconds. Among Japanese-English interlocutors, Mocha’s speech showed the longest duration of alternation, resulting in more than 80 seconds in alternated sentences. For the Korean-English data, Joe’s brother spent more than 70 seconds in alternated sentences.

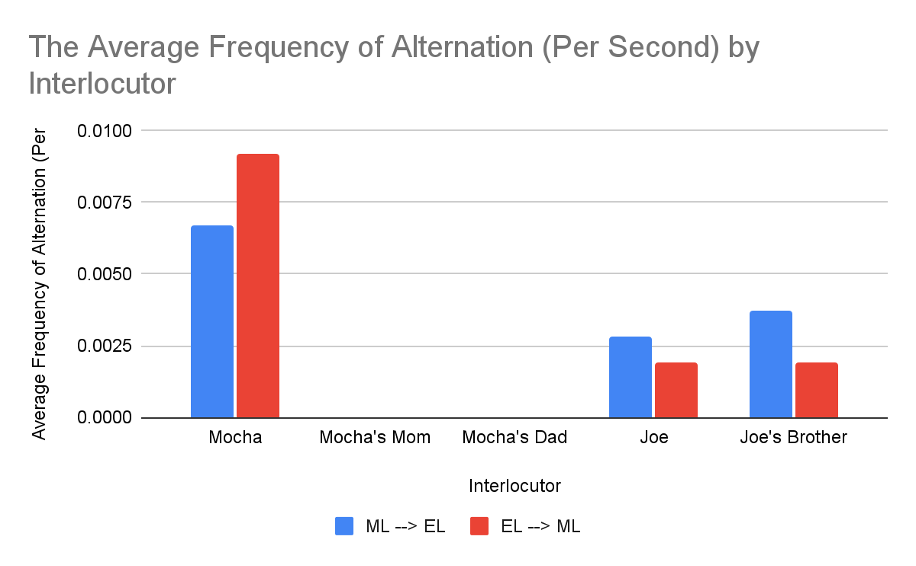

Similarly, in Table 3, Mocha and Joe’s brother exhibited the highest average frequency of alternation (in their respective bilingual group). The frequency was calculated by dividing the number of total times each interlocutor used alternation in his or her speech, by the total duration of each conversation.

Based on our findings, we predict that those with more years of experience speaking in their first language tend to engage in alternation more. In our data set, Mocha and Joe’s brother have had more years of speaking & learning their first language at their home country (Mocha, 21 years; Joe’s Brother, 20 years), in contrast to their family members (Mocha’s parents, 19 and 3 years; Joe, 12 years at home). We hypothesize that a bilingual speaker with a stronger foundation in their first language may feel more comfortable alternating to a foreign language, although other factors not addressed in this study such as the speech content, psycho-social relationship with the interlocutor, and environmental factors may equally play a role.

Conclusions

The formal theorization of Myers-Scotton’s Matrix Language Framework hypothesis (1993, 2009) formed the groundwork for the study of bilingual CS since the 1990’s. Our empirical quantitative study focused on a syntactical analysis of how 1.5 and 2nd generation Japanese-English and Korean-English bilingual speakers CS today, offering evidence against the two basic principles of the MLF Hypothesis. We also demonstrate a positive correlation between the engagement in alternation and the proficiency in the bilingual speaker’s first language.

Our findings aim to advance the study of modern bilingual CS by pointing out that scholars must continue to understand the syntactic inner-mechanism of the more sizable bilingual population’s CS, in particular, the East Asian language-English pair. This is because of the greater socio-linguistic implications these studies can have, such as the reduction in the generational gap between millions of Asian immigrant parents and millennial children, and the broader academic recognition of the quickly-changing nature of multilingual culture in Asia in this global age.

We invite scholars to continue to look into areas not addressed in this study, such as the role of psycho-social elements, level of intimacy between interlocutors, and other greater socio-linguistic and anthropological factors that may affect how future bilingual speakers may engage in CS.

Lastly, our findings stress the importance of being well-versed in one’s first language, as our study shows that a bilingual speaker who has spent more years speaking in his or her first language finds it easier to fully switch to a different language than those who have had less years of experience learning their mother tongue language at their home country.

References

Backus, A. (1992). Patterns of language mixing: a study in Turkish-Dutch bilingualism.

Bokamba, E. G. (1988). Code-mixing, language variation, and linguistic theory: Evidence from Bantu languages. Lingua, 76(1), 21-62.

Code-switching (G4) – Language Contact. Language Contact. (2011, October 8). https://sites.google.com/site/hongkonglinguistics/Downhome/Topic1/part1knowledgerepresentationinprolog20. Last accessed 10/08/2021.

Indian immigrants in the Unites States (2020) Migration Information Source. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/indian-immigrants-united-states-2019. Last accessed 10/08/2021.

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Common and uncommon ground: social and structural factors in codeswitching. Language and Society, 22 (pp. 475-503).

Myers-Scotton, C., & Jake, J. (2009). A universal model of code-switching and bilingual language processing and production. In B. E. Bullock & A. J. Toribio (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of linguistic code-switching (pp. 336–357). Cambridge University Press.

Code-switching (G4) – Language Contact. Language Contact. (2011, October 8).

https://sites.google.com/site/hongkonglinguistics/Downhome/Topic1/part1knowledgerepresentationinprolog20.

Shim, Ji Young. 2021. OV and VO variation in code-switching (Current Issues in Bilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press.