Sarah Belew, Jacques Gueye, Kaley Phan, Boyi Zheng

In this study, we analyze the linguistic behavior of antagonists in psychological thriller movies in order to understand/index the features in their language that make them “creepy”. We chose 4 different films to view: Misery (1990), Silence of the Lamb (1991), The Lovely Bones (2009), and Gone Girl (2004). From these films, we analyze how abnormality is constructed using subtle linguistic behaviors of word choice, intonation, and sociolect. We theorize that abnormality in the character’s linguistic traits is rooted in deviation of their demographic’s language pattern and what is considered appropriate for social interaction, or “creepy.” As a result, we find that the antagonists are aligned in their sociolects, word choice patterns of calling the antagonist’s name with great frequency, and that female antagonists have a “(Rise)-Rise-Fall” pattern in prosody. These marked patterns come together to create vivid, memorable characters that are unmistakably creepy.

Introduction and Background

What is creepiness? McAndrew and Koehnke identified the study of creepiness as a major gap in the scientific literature (2016). Their study identified creepiness correlates, such as gender identity (“being male”), physical traits (“having greasy hair”), and behavioral patterns (“stood too close to your friend”), concluding that creepiness is detected when people perceive an ambiguity of threat, often interpreted as a sexual threat among female participants.

We are unsatisfied with this approach. By eliciting people’s understanding of creepiness, perhaps we receive nothing more than a “creepiness profiling” mechanism, echoing the findings of Implicit Association Test studies conducted on racial stereotypes (Oswald et al, 2013). Are certain racial groups perceived as possessing more ambiguity of threat? Can women ever be creepy? Since our social life is riddled with implicit biases, this strand of study demands a more experimental approach that challenges our biased perception. Scripted Fictional Content (SFC) has the transformative potential in understanding the depth of this human emotion. The four psychological thriller films that we watched for our studies, including Misery (1990), Silence of the Lamb (1991), The Lovely Bones (2009), and Gone Girl (2004) demonstrated that creepiness does not rely on stereotypes and non-normativity known to our daily life. The mismatch between language stereotypes, creepiness assumptions, and the language performance confirm that actors often combine verbal strategies that run counter to expectations of norms but are not abnormal in a caricatural sense. This confirms the third-wave sociolinguistic assumption of the speaker’s agency (Eckert, 2012, Bell and Gibson, 2011). Overall, we find that actors do not achieve creepiness by piecing together socially neutral elements in the context of the movie plot and the character, which come together to deliver the creep.

Methods

In this study, we use sociophonetic and behavioral patterns to describe the technique of character building. We examined over eight hours of audiovisual media to develop a corpus study, manually coding all the speech of antagonists for marked patterns. We also listen to the other characters to qualitatively compare, so that we may develop a sketch of each antagonist including sociophonetic and rhetorical strategies. For the quantitative analysis, we pick creepiness correlates in their coded context to establish a statistical distribution per film.

In conducting this pilot study, we take the third-wave linguistics assumption that speakers consciously use sociolinguistic elements. Since there is a gap in the literature, we only landed on prosody, register (word choices), and sociolect as our relevant variables after preliminary viewing. Many previous studies demonstrated that affective prosody allows great intra-speaker speech variety, and plays a critical role in emotion expression (Frick 1985). On the other hand, socio-prosody study of inter-speaker variation is a field at its early development (Holliday 2021). Nevertheless, the evidence in our corpus convinced us that creepiness correlates, such as the markedness of the (rise)-rise-fall prosody has both intra-speaker patterns (reserved for narrative manipulation), and inter-speaker patterns (indexing non-standard dialects, feminine speech).

For our most nuanced and productive variable, the (rise)-rise-fall pattern, we have provided an edited video clip for demonstration purposes. Our coding of this pattern has followed the following rule-of-thumb criteria: (1) well-defined rising accent (L+H*) followed by a falling accent (H+L*) and a low boundary tone (L%), often the result of emphasizing the penultimate word (Beckman & Ayers 1997) (2) exclude rising in questions, unmarked rising in enumeration and long words (3) usually occurs toward the end of an utterance (4) characteristically violating the Strong-Weak alternation in modal rhythm (Kiparsky 2014).

Here is an edited clip from Gone Girl (2004), where Amy Dunne uttered 50 instances of characteristic (rising)-rising-falling speech in the course of a 7-minute monologue.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Tcc106ftXEQYeOe08oTVmTule9zlkP40/view?usp=share_link

Results and Analysis

1. Word Frequency Analysis

The following word clouds (Figure 1) visualize how antagonists in our corpus exhibited two discourse behaviors that made their interlocutor and the audience uncomfortable. Amy Dunne (Gone Girl), Anne Wilkes (Misery), and Hannibal Lector (Silence of the Lamb) all have the name of the protagonist as their most frequent item, showing their unhealthy obsession with them. They all engaged in extensive manipulation of the protagonists, calling them by name to draw their attention. This article by Michigan State University elaborates on some of the psychology behind using someone’s name, including manipulation. George Harvey (The Lovely Bones) is the only character that does not share this pattern, particularly because of a lack of dialogue between the two (although he does refer to the protagonist by her last name occasionally). The second behavior is the use of words that may appear manipulative. These words include “know”, “think”, “see”, etc. Under different contexts, these words are used in dialogue to guide the protagonist’s thinking and actions. For example, consider the following line in “Misery” by Annie:

ANNIE: I know you didn’t mean it when you killed her, and now you’ll make it right.

In this context, the antagonist is telling the protagonist what she believes he is thinking, in a way that he has no choice but to accept. With the other high frequency words, it is common that the antagonist used it in the same way: to make controlling statements or pure assumptions. Phrases such as “you know”, “I think you” and “you see”, were very frequent ways that these words were being used.

2. Prestigious, Psychopathic Dialects and Rhetorics

In the three antagonist-centered psychological thrillers (excluding The Lovely Bones), we see antagonists being portrayed as highly intelligent, socially prestigious characters, only to be revealed as vile, manipulative psychopaths. They are Harvard-graduate writers, head nurses, and renowned psychologists, all having high social standing. Based on the story setting and the voice acting, we qualitatively judge Amy to have virtually no accent for her background in New York, and Anne Wilkes to leave a Mid-American housewife impression but no recognizable Bakersfield phonetic feature as well. Hannibal Lector, on the other hand, speaks with the highly prestigious Mid-Atlantic English, plus Hollywood Golden Age paralinguistic sound quality: consistent nasal leakage, strong twang (forte consonant articulation), drawl (prolonged vowels), seldomly enunciating rhotics. These patterns are close to Katherine Hepburn, credited as the actor that popularized this accent (Wang 2014). However, this style of speech has been long obsolete, and the decision to act in such an accent, combined with a strange melodic quality resembling Truman Capote, the actor Anthony Hopkins has truly created an uncanny accent.

On the level of rhetoric, all three of these antagonists use elaborate rhetorical strategies. Hannibal is known for his cruel puns (‘having a friend for dinner’, implying cannibalism). As a writer, Amy uses her rhyming puzzles and vulnerable writing style to play the innocent, bubble-headed victim of a domestic murder, leaving the world lamenting her disappearance and his husband being hated by everyone. Even Anne Wilkes, the least articulate of them, uttered rhymed lines in a confession of love for Paul, showing a mastery of poetics:

The rain, sometimes it gives me the blues./ When you first came here, I only loved the writer part of Paul Sheldon. But now I know I love the rest of him, too. / I know you don’t love me. Don’t say you do./…. You’ll never know the fear of losing someone like you… /That’s very kind of you, but I bet it is not altogether true.

George Harvey, the antagonist of The Lovely Bones, has to be analyzed as an exception. Being a protagonist-centered film, the picture showed him as a more marginalized, conventionally creepy character. His speech patterns always sound like an act, given that there is little exposure to the nuances and complexity of his persona. He uses underprivileged elements preferred by men, sometimes exhibiting free in~ing, /s/~/ʃ/ alternation (Hall-Lew et al, 2021, Labov, 1966). Conspicuously, the alternation seems to happen when he is confronted by somebody else and putting on pretension. If we accept this theory and suggest that George does not exhibit his authentic speech pattern, it does not pose a problem to our thesis.

3) Prosody Distributional Analysis in the Sociolect Context

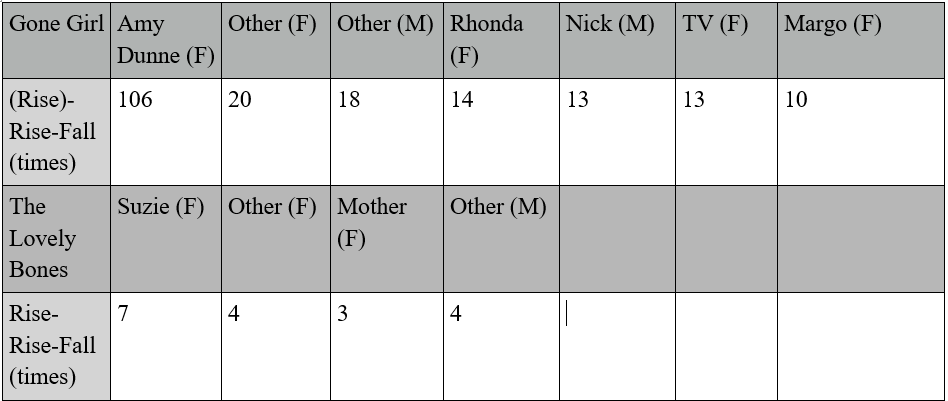

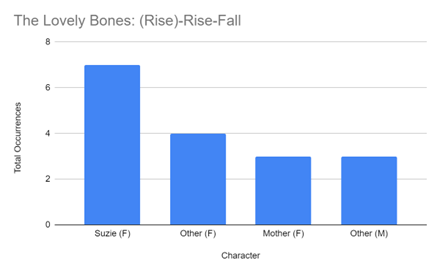

In watching Gone Girl, Lovely Bones, and Misery, we find the distribution of the (Rise)-Rise-Falling pattern to be precisely patterned with three social factors: gender, region of origin, and positions of power.

What first drew our attention was the clip played in the method section, in which Amy Dunne displayed an impressive array of the said pattern – contributing fifty out of 194 total occurrences of the pattern in the film within seven minutes. When we look at the setting of Gone Girl, in suburban Missouri, we can make sense of this pattern as a regionalism for most of the occurrences, since most characters, except for Nick, Amy, and Margo, display a non-standard accent. Perhaps due to the cultural marginality of the American Midwest, we do not find the renowned monophthong /o/ instead of /əʊ/ (‘b-oh-t’ for BOAT [boːt]), /æ/ heightened to be /e/ (‘behg’ for BAG [beg]), but instead recognize the vowel chain shift nascent to the American south (/a/ for /aɪ/, /ei/ for /ɪ/, and so on) (Labov et al, 2005). As in the previous analysis, the character Amy is designed as a native New Yorker with high social standing, often showing snobbery and resenting the simple life in the Missouri countryside. The (Rise)-Rise-Fall pattern feels quite out of place in her standard American repertoire of sounds, and we are inspired by the clip to say that the voice actors use this strategy to show a dominance over the narrative – for the first half of the film, she has set herself up as the narrator, but is later to be revealed as a psychopathic liar who is obsessed with manipulating herself and others. This agrees with the common perception of the prosody pattern- salient in TV announcements, radio shows, and advertisements. When the audience saw the run-away Amy put up the facade of a New Orlean housewife, she experienced another spike of (Rise)-Rise-Fall patterns, only that this time it is contextualized by a clear southern accent. This time, her interlocutor speaks with the same southern accent and similar rise-fall patterns. This gives us the final confirmation that the pattern we discovered is indeed marked and regionally conditioned.

The same findings are confirmed in Misery, even though a complete count of the relevant token has not been possible due to copyright reasons, we have an observation that exactly follows the above: Anne Wilkes speaks a normative accent, and only uses the (rise)-rise-fall pattern to fulfill the function of manipulation, infamous scenes such as the iconic “I’m your number one fan”. Otherwise, the same pattern only occurred in the conversation between two southern speakers, Sheriff Buster and his wife.

Should this prosody pattern also be found among male antagonists? We do not find this to be the case, but the statistics from the three films we coded (excluding Silence of the Lamb) all speak to the fact that (Rise)-Rise-Fall indexes female identity. In all three films, male utterances of the phrase make up less than 25% of the total tokens, and characters who consistently speak this way are all decidedly Southerners. The Lovely Bones showed the same consistent pattern, with the prosody of Suzie’s mom functioning as a signal for a controlling character who commands her children to follow rules – similar to the manipulative personalities we saw.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our research has yielded a small contribution to the understanding of the interactions between language and media, by providing insights into the intricate ways in which language and presentation can be used to create a sense of creepiness or psychopathy in characters. By exploring the techniques employed by the antagonists in the four films we analyzed, we have uncovered a diverse range of patterns that contribute to the development of creepy characters.

It is important to acknowledge that our study represents a small sample size and may not be generalizable to all media or contexts. However, with our final results, we can contribute to a deeper understanding of this popular media phenomenon. We hope that our research will provide further insights into this topic, as there is much more to be learned about the nature of language in the media and our relationship with both.

At the end of our project’s journey, our findings have uncovered the intricate ways in which language and presentation can be used to create a sense of creepiness or psychopathy in characters. The identification of common patterns in the techniques used in the four films we studied is a crucial step in the advancement of our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

In conclusion, our research has provided valuable insights into the complex phenomenon of creepiness in the media. Our analysis of language and presentation techniques used to create creepy characters can contribute to a deeper understanding of human psychology and social behavior. Our study also highlights the importance of representation and diversity in media and has practical applications for filmmakers. We hope that our research will inspire further investigations into this fascinating area of study.

References

Bauman, R., & Briggs, C. L. (1990). Poetics and performances as critical perspectives on language and social life. Annual review of Anthropology, 19(1), 59-88.

Beckman, M. E., & Ayers, G. (1997). Guidelines for ToBI labeling. The OSU Research Foundation, 3(30), 255-309.

Bell, A., & Gibson, A. (2011). Staging language: An introduction to the sociolinguistics of performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 15(5), 555-572.

Buckland, W. (2021). Feminism, narrative, authorship: (Gone Girl and Orlando). In Narrative and Narration: Analyzing Cinematic Storytelling (pp. 65–80). Columbia University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/buck18143.9

Cao, H., Beňuš, Š., Gur, R. C., Verma, R., & Nenkova, A. (2014). Prosodic cues for emotion: analysis with discrete characterization of intonation. Speech prosody (Urbana, Ill.), 2014, 130–134. https://doi.org/10.21437/SpeechProsody.2014-14

Clopper, C. G., & Smiljanic, R. (2011). Effects of gender and regional dialect on prosodic patterns in American English. Journal of phonetics, 39(2), 237-245.

Demme, J. (Director). (1991) The silence of the lambs [Film]. Strong Heart Productions.

Fincher, D. (Director). (2014). Gone girl [Film]. Twentieth Century Fox.

Jackson, P. (Director). (2009) The lovely bones [Film]. Dreamworks Pictures.

Jacquemet, M. (1999). Conflict. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 9(1/2), 42–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43102422

Holliday, N. (2021). Prosody and sociolinguistic variation in American Englishes. Annual review of linguistics, 7, 55-68.

Hall-Lew, L., Moore, E., & Podesva, R. (Eds.). (2021). Social meaning and linguistic variation: Theorizing the third wave. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108578684

Kiparsky, P., & Youmans, G. (2014). Rhythm and meter: Phonetics and phonology, Vol. 1. Academic Press.

Labov, W. (2006) The social stratification of English in New York City—Google Books. (n.d.). Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Social_Stratification_of_English_in/bJdKY0mZWzwC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=william+labov+1966+social+stratification&pg=PA3&printsec=frontcover

Labov, W., Ash, S., & Boberg, C. (2008). The atlas of North American English: Phonetics, phonology and sound change. Walter de Gruyter.

Leistedt, S. J., & Linkowski, P. (2014). Psychopathy and the cinema: Fact or fiction? Journal of Forensic Sciences., 59(1), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12359

Reiner, R. (Director). (1990) Misery [Film]. Castle Rock Entertainment.

Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2), 361. https://doi.org/10.2307/413107

Langlotz, A. (2017). 17. Language and emotion in fiction. In 17. Language and emotion in fiction (pp. 515–552). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110431094-017

McAndrew, F. T., & Koehnke, S. S. (2016). On the nature of creepiness. New Ideas in Psychology, 43, 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2016.03.003

Oswald, F. L., Mitchell, G., Blanton, H., Jaccard, J., & Tetlock, P. E. (2013). Predicting ethnic and racial discrimination: A meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032734

Stephenson, V. L., Wickham, B. M., & Capezza, N. M. (2018). Psychological abuse in the context of social media. Violence and Gender, 5(3), 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2017.0061

Wang, C. (2014). A Sociophonetic analysis of American theater speech as exemplified by Katherine Hepburn’s filmography. https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/handle/10066/13761

Werner, V. (2022). Pop cultural linguistics. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.999

Wolter, Keely (2022) FULL INTERVIEW: Accent and dialect coach Keely Wolter talks about dat dere “Midwestern accent.”—YouTube. (n.d.). Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vC4gyH4nhIw

Absolutely wonderful work, but just a note: Third Wave points out that agentive language use is usually NOT conscious! “most of what we do, we do unconsciously” (Eckert 2019: 3).

Eckert, Penelope (2019). ‘The individual in the semiotic landscape’, Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 4(1): 1–15.

Please revise this as it’s a widespread misunderstanding and a shame to see it perpetrated. Thank you!