Namrata Deepak, Renee Rubanowitz, Kylie Shults, Alik Shehadeh, George Faville

Iconic TV catchphrases like “Yada-yada-yada,” “D’oh,” That’s what she said,” and “Bazinga!” have been seamlessly integrated into our everyday conversations. Such a phenomenon prompts amusing discussions and questions surrounding the relationship between real-world conversation and on-screen dialogue. While some aspects of on-screen language, like exaggerated accents or absurd dialogue, are accepted as fictional, others are more representative of natural everyday speech. This study delves into the linguistic choices made by sitcom writers to make fictitious situations more comedic and relatable, contrasting our findings with real-world conversations that lack such agendas. In examining the intentional use of linguistic choices by screenwriters to enhance comedic effects in television sitcoms, we hypothesize that scripted language possesses observably fewer contractions, first-person pronouns, second-person pronouns, present tense verbs, more prepositions, and increased word length when compared directly to natural conversation.

Expanding on Biber’s Theory of Multidimensional Analysis (1992) and Quaglio’s analysis of Friends (2009), our research deconstructs and compares the dialogues from The Office (U.S.), Modern Family, and Community with comparable, real-world conversational data obtained from the Santa Barbara Corpus of Spoken American English (Du Bois, 2000-2005). Using Biber’s Factor 1 as a measuring tool that focuses on colloquial language, we selected specific linguistic features to measure their frequency in sitcom clips versus comparable real-life conversations to obtain evidence to explore our hypothesis further.

While our findings generally align with existing evidence for our identified linguistic features, the extent of differences between scripted and natural language could have been more pronounced. Consequently, further research may also be warranted, as our hypothesis was disproved for word length and prepositions, indicating a more remarkable similarity between TV dialogue and natural conversation than expected. Nevertheless, our study contributes to ongoing discourse on the relationship between on- and off-screen language, offering valuable insights into the linguistic choices that shape perceptions of comedic situations and beloved characters.

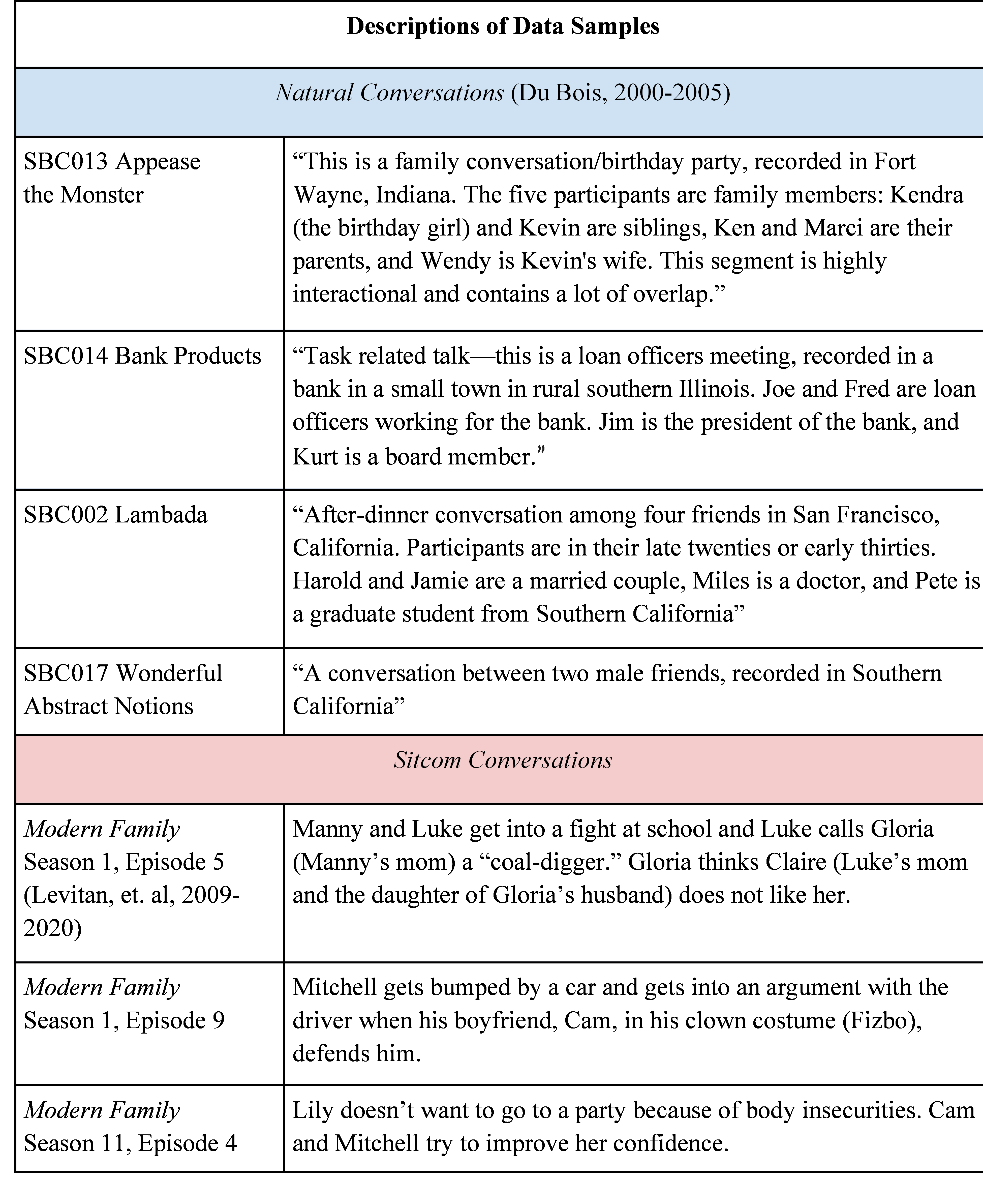

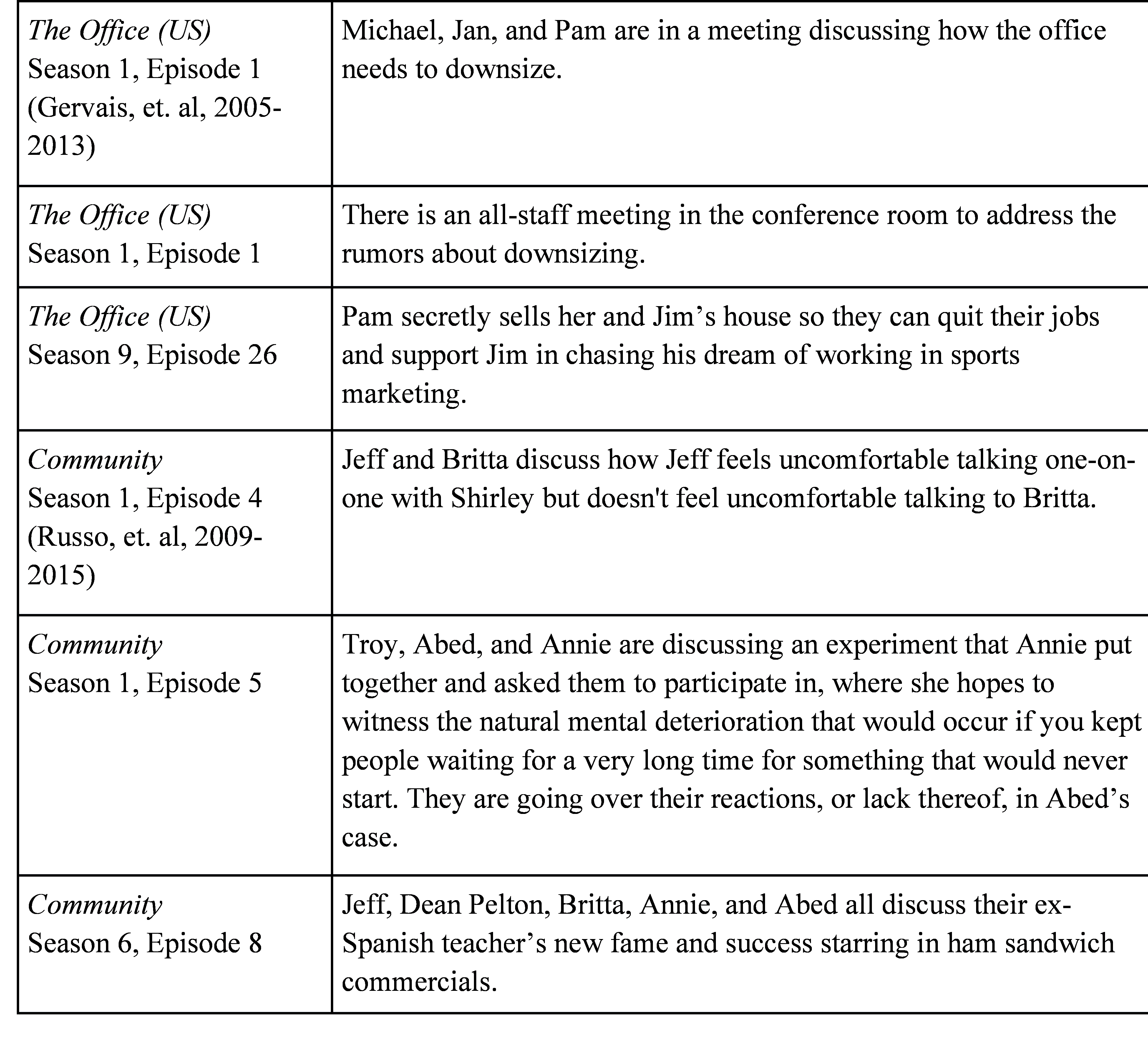

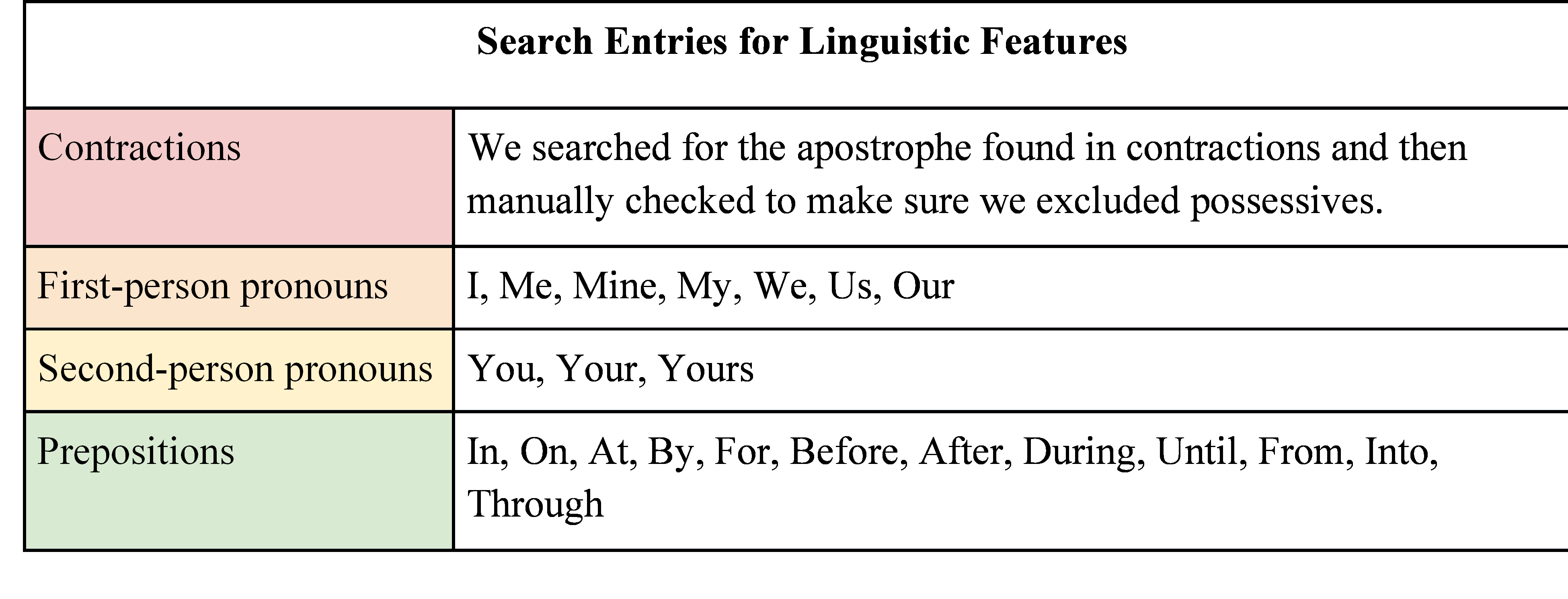

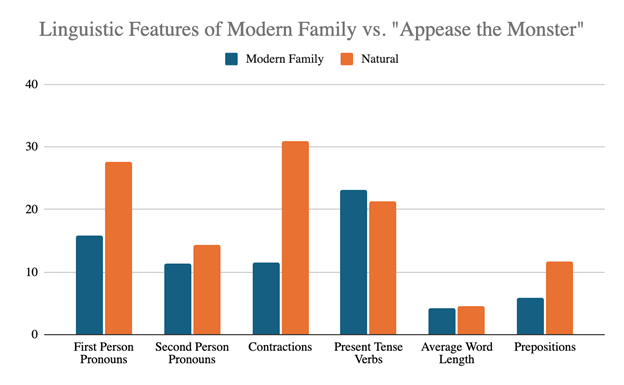

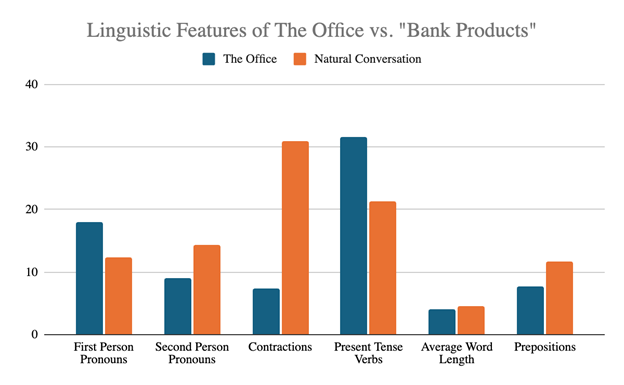

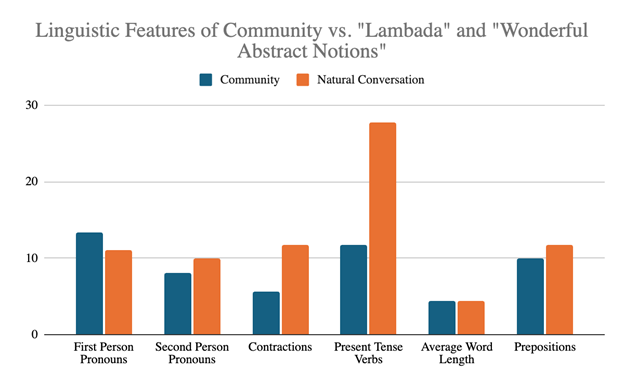

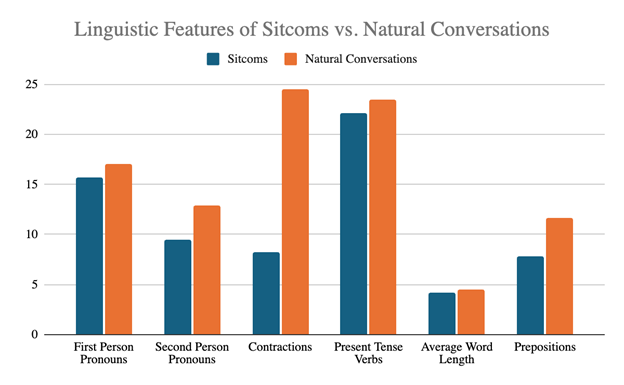

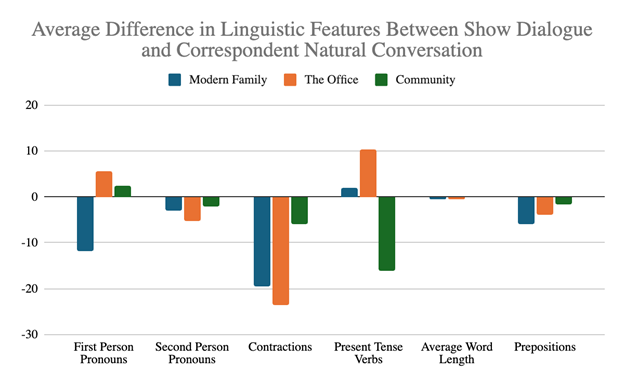

Introduction and Background Situational comedies, or sitcoms, tend to put relatable yet exaggerated characters in outlandish situations to prompt entertainment and humor in audiences (Simply Sitcoms; The situations that precede the comedy). Think about shows like Modern Family, where miscommunications are key to every episode, or The Office (U.S.), where the seemingly ordinary workplace is exaggerated by eccentric characters like Michael Scott. As sitcoms become more intertwined with American popular culture, a fascinating question arises: Do they accurately capture the subtleties of natural conversation? Further inquiry into scripted banter reveals a core sociolinguistic component – screenwriters make deliberate choices about language that have implications for language learning, language evolution, and more. This study aims to analyze the linguistic differences between dialogue in U.S. sitcoms and natural conversations, focusing on specific linguistic choices that signal colloquialism. Guided by the question – “To what extent does scripted language represent actual language in depictions of humor?” – our team hypothesizes that the screenwriters for Modern Family, The Office, and Community intentionally use linguistic choices and manipulation to augment comedic effects, resulting in dialogue dissimilar from natural conversation. Specifically, we predict that scripted language has fewer contractions, first-person pronouns, second-person pronouns, more prepositions, and shorter word lengths. Our target population consists of the participants in the selected conversations: the characters in Modern Family, The Office, and Community, as well as the actual family members, coworkers, and friends in the recordings we used. Together, these participants form a sample of sitcom characters and a sample of the general American population, which we will contrast to test our hypothesis. To further analyze and gather more resources to support our investigation, we turned to previous case studies exploring scripted language’s limitations compared to organic speech, including a study on the sitcom Friends (Quaglio, 2009). Additionally, we referenced Bednarek’s study on Gilmore Girls (2011), which analyzes how a show’s dialogue contributes to creating a specific kind of dialogue unique to itself and defining the genre it is a part of. Though we are expanding on past theories, we acknowledge the need for extended research on more contemporary and diverse sitcoms for the most comprehensive overview of these rich hypotheses. Methods Our research question led to three critical questions when designing our study: what data are we using, what linguistic features are we focusing on, and how will we collect data? What data are we using? For data, we chose to look at situational comedies since they tend to mirror (and potentially exaggerate) everyday situations. We transcribed 2-3 minute conversations from the first and last seasons of Modern Family, The Office, and Community, constituting our scripted dialogue corpus. We then found contextually similar real-life conversations to each show (between family members, coworkers, and friends, respectively) from the Santa Barbara Corpus of Spoken American English and chose three 2-minute segments from each one to transcribe. What linguistic features are we focusing on? When selecting our linguistic features, we used Factor 1 of Biber’s Multidimensional Analysis as a starting point since it was theorized to show the most significant difference between humor and natural conversation (Eberhardt, 1988). We believe a crucial reason for this difference is because of colloquialism, which is what Factor 1 measures – in real life, we are likely to be more colloquial and use less intentional language, unlike TV, where dialogue is meant to produce entertainment. We focused on contractions, first-person pronouns, second-person pronouns, present tense verbs, prepositions, and word length. How did we collect the data? For contractions, first-person pronouns, second-person pronouns, and prepositions, we used a software called AntConc to measure the frequency of each variable within each conversation (see the figure below for the specific terms we used). We counted present tense verbs manually. For word length, we took the total number of characters within the dialogue and divided it by the number of words to produce an average character length for each word. Results and Analysis After we collected our data, we mapped it visually, with “Words Per Minute” as the y-axis and “Linguistic Features Analyzed” as the x-axis, including columns for each scenario. When analyzing and interpreting the data, we focused on the most significant disparities between linguistic features in the sitcoms and the in-person interactions. We also calculated the average number of differences across all linguistic features compared to natural conversations. Modern Family Below are excerpts and transcripts from a Modern Family (Levitan, et. al, 2009-2020) episode and the “Appease the Monster” family conversation from the Santa Barbara Corpus of Spoken American English (Du Bois, 2000-2005). The most apparent difference between the two sources is the degree of interruption – the natural conversation shows much more overlap. At the same time, the sitcom mostly has one line occurring at a time. This variation can mainly be attributed to the practical demands of filming a TV show, so we focused on more specific word choices to see if the actual language (rather than its delivery) also differs. We assessed 1:45-2:30 of the Modern Family clip below: We assessed 0:00-1:00 of the “Appease the Monster” conversation here: Audio Recording of the “Appease the Monster” Conversation (0:00-1:00) After measuring our selected linguistic features within the Modern Family and “Appease the Monster” conversations, we can see in Figure 5, illustrating linguistic features on the x-axis and frequency on the y-axis, that natural conversations have more first-person pronouns, second-person pronouns, and contractions – all supporting our hypothesis. However, the remaining categories – present tense verbs, average word length, and prepositions – all display a relationship that is inverse to the predictions of our hypothesis. The Office As we hypothesized, The Office comparison chart above shows that natural conversations use more first-person pronouns, second-person pronouns, and contractions. However, the data in Figure 6 does not substantiate predictions that natural conversations would use more present tense verbs, shorter word lengths, and fewer prepositions. Community We can see in the Community comparison chart above that while natural conversations have more second-person pronouns and contractions, the rest of the linguistic categories display an inverse relationship to what was predicted, subsequently disproving our hypothesis. Synthesis Thus, Figure 8, which illustrates the average difference between all of our observed television programs and real-life conversations, demonstrates that sitcoms followed our hypothesized patterns for first-person pronouns, second-person pronouns, contractions, and present-tense verbs. However, when looking at average word length and preposition frequency, the sitcoms showed results that were opposite to what was expected, with shorter words and fewer prepositions. An important note is that, except for contractions, the differences seen are very slight. To zoom in a little further, Figure 9 complicates our results as we look at the specifics of each show. Modern Family is the only show that demonstrated fewer first-person pronouns than the corresponding natural conversation. Community is the only show with fewer present tense verbs than its corresponding natural conversation, per our hypothesis. The Office appears the most natural, disobeying our hypothesis for the linguistic features of word length and prepositions. As mentioned, all three shows did not follow our hypothesized difference in average word length or prepositions, suggesting that our sitcom data is considerably closer to natural conversation than expected. Discussion and Conclusion From the data analysis we conducted, we concluded that while there is a slight difference between TV and natural conversations (especially for first-person pronouns, second-person pronouns, contractions, and present tense verbs), the differences are insignificant and do not indicate much deviation. Additionally, the data disproved our hypotheses around word length and prepositions; regarding these features, sitcoms were more “natural” than actual natural conversations. However, we acknowledge the fact that our investigation had limitations. Due to the narrow timeline of our project this quarter, we did not collect and analyze as much data as we would have hoped in order to find more substantial differences between scripted and non-scripted language. Revisiting our initial research question: To what extent does scripted language represent actual language in depictions of humor? Initially, our data may seem surprising since we found fewer differences than expected, but there might be a reason why these sitcoms tend to lean more toward natural-sounding conversations. The craft of screenwriting tiptoes on a delicate balance between accurately portraying real-life scenarios and creating humorous and engaging dialogues meant to captivate audiences. Our three Emmy Award-winning shows have achieved widespread acclaim and popularity, and part of this success can be attributed to linguistics, as their language choices play a crucial role in effectively resonating across various audiences and demographics. TV dialogue has far-reaching linguistic influence, especially in the language learning classroom, where teachers often encourage students to use sitcoms (and other scripted content) to practice English and attain competency. The nuances of our data suggest that while the language English learners are studying has a certain degree of difference from conversational English, it still shares similarities to natural language and, thus, may serve as a helpful tool. Taking our research in conjunction with Quaglio’s study on Friends (which did find a significant difference) suggests that more research is needed to see how this could affect the language learning process and whether sitcoms are practical language learning tools (Quaglio, 2009). Additionally, Quaglio’s findings suggest that TV dialogue is its own register of English, different from the spontaneous and natural conversation it hopes to (and is assumed to) emulate. Our data complicates this theory, indicating that this register is becoming closer and closer to standard/conversational English with our three sitcoms or that more research is needed to ferment a pattern. To read more about the role of TV in social development and cultural unity, read this blog post: “Role of Television in Sociocultural Development of a Society.” To see more concrete examples of the linguistic reach of TV, read this article about words and practices that natural conversation has borrowed from TV dialogue: 10 Ways Television Has Changed the Way We Talk. To expand on this topic further, it would be important to attain cross-linguistic data. How do these patterns of difference occur in other languages? Due to the importance of media to culture, this would help clarify whether TV dialogue is simply a register of English or a cross-cultural phenomenon. References Biber, D. (1992). On the complexity of discourse complexity: A multidimensional analysis. Discourse Processes, 15(2), 133–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638539209544806. Bunniefuu. (2013, May 17). 09X24/25 – finale. The Office Transcripts. https://transcripts.foreverdreaming.org/viewtopic.php?t=25498#google_vignette. Du Bois, J. W, et. al (2000-2005). Santa Barbara Corpus of Spoken American English | Department of Linguistics – UC Santa Barbara. UCSB Linguists. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/research/santa-barbara-corpus. Eberhardt, S. (1988). Identifying_Multidimensional_Patterns_across_Register_Variation. Retrieved May 6, 2024, from https://www.unibamberg.de/fileadmin/engling/fs/Chapter_21/Index.html?23DimensionsofEnglish.html. Gervais, Merchant, et. al (Executive Producers). (2005-2013). The Office [TV Series]. Deedle-Dee Productions; 3 Arts Entertainment; Shine America; Universal Television. Hoey, E. (2018). Conversation analysis. https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_2328034_3/component/file_2328033/content. Levitan, Lloyd, et. al (Executive Producers). (2009-2020). Modern Family [TV Series]. Steven Levitan Productions; Picador Productions; 20th Century Fox Television. Nini, A. (2019). The Multi-Dimensional Analysis Tagger. In Berber Sardinha, T. & Veirano Pinto M. (eds), Multi-Dimensional Analysis: Research Methods and Current Issues, 67-94, London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic. Quaglio, P. (2009). Television Dialogue and Natural Conversation: Linguistic Similarities and Functional Differences. Corpora and Discourse, 189-210. https://aogaku-daku.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Television-dialog-corpora-and-discourse.pdf. Russo, Russo, Harmon, et. al (Executive Producers). (2009-2015). Community [TV Series]. Krasnoff/Foster Entertainment; Russo Brothers Films; Harmonious Claptrap; Universal Televsion; Sony Pictures Television; Yahoo! Studios. The Office (USA) – season 1 episode 1: “pilot.” Genius. (2005). https://genius.com/The-office-usa-season-1-episode-1-pilot-annotated. Zago, R. (2017). English in the Traditional Media: The Case of Colloquialisation Between Original Films and Remakes. Transnational Subjects Linguistic Encounters: Selected papers from XXVII AIA Conference, 2, 91-104. https://unora.unior.it/bitstream/11574/176955/1/Atti%20AIA%20curatela.pdf#page=119.