Kathryn Cunningham, Anna Tobey, Leia Broughton, Maya Athwal, Nicole Pacheco

Note: This article was written in Spring 2024, prior to Biden stepping down from the presidential race and Trump winning the 2024 presidential election.

Are all news headlines made equal? For our project, we analyzed the potential effects of framing in online news headlines on readership responses in the comments. Digital tools for political discourse are becoming increasingly popular, and we want to investigate how framing in the media can influence political cognition and amplify the political polarization we see in comment sections today. We hypothesized that different framings in headlines would provoke politically biased emotional responses against the opposing political party. We conducted critical discourse analysis of six different headlines pertaining to a singular political event — Michael Cohen’s testimony against Donald Trump — on two news sites from each of the following categories: left-leaning, right-leaning, and neutral. We then compared these analyses of the lexical and syntactic choices used to frame Cohen and Trump with the corresponding comments on each article. We observed high-frequency keywords and identified eight categories for different comment types, considering how each headline could have prompted the intense responses we saw. The results of this project are important in understanding the power of party framing and how it can divide us simply through subtle choices in language.

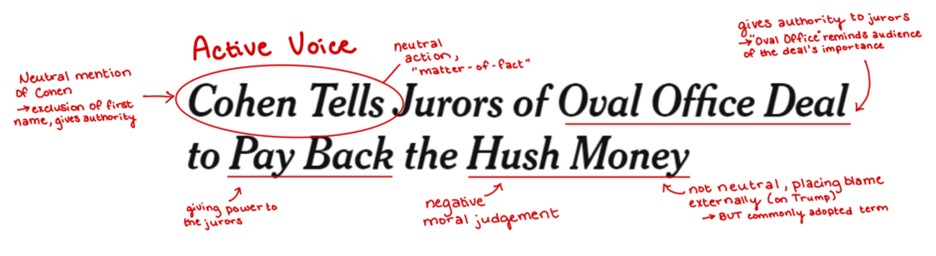

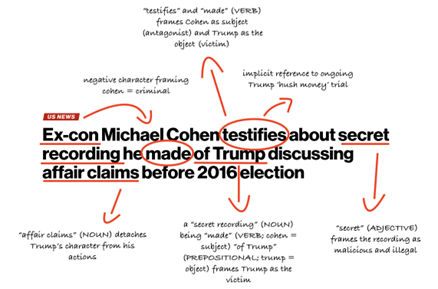

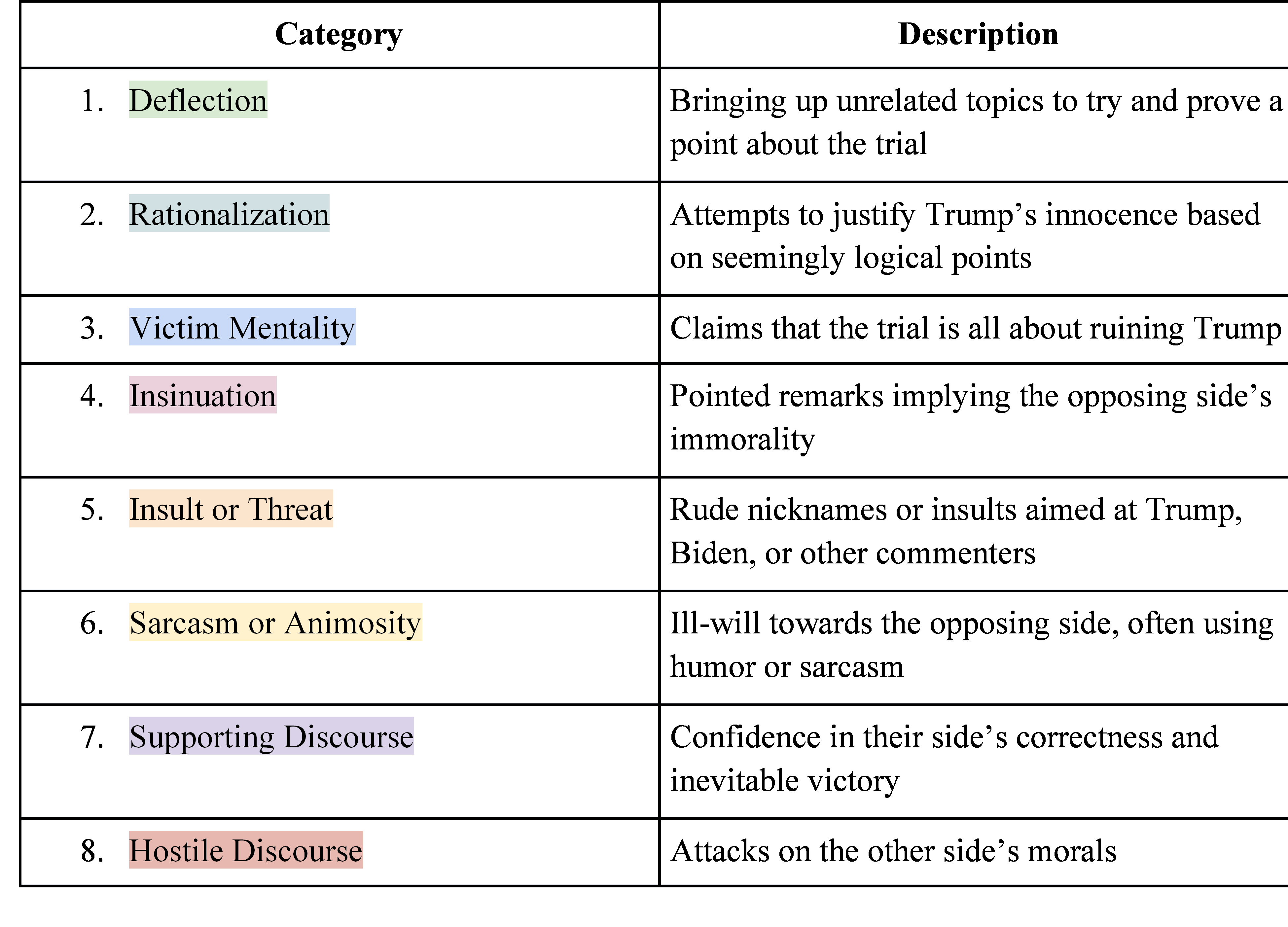

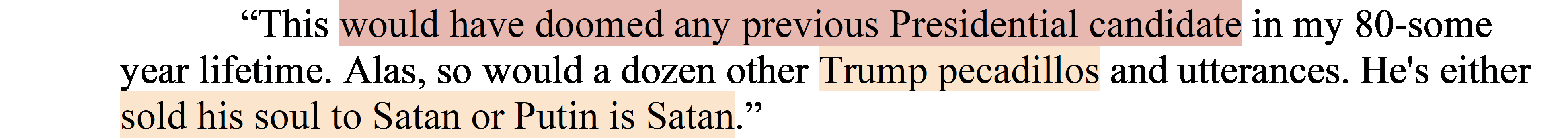

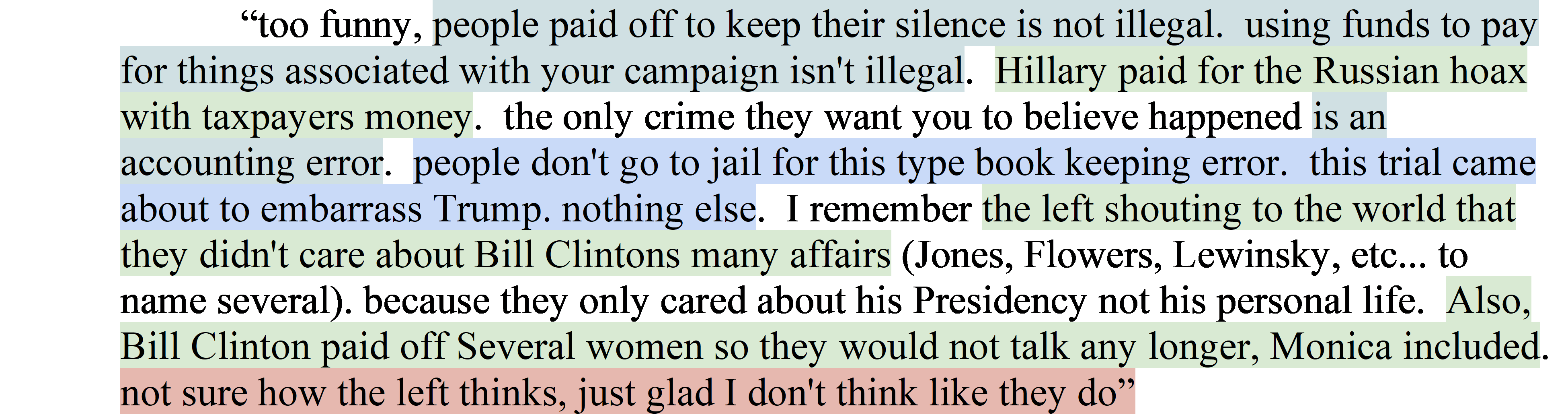

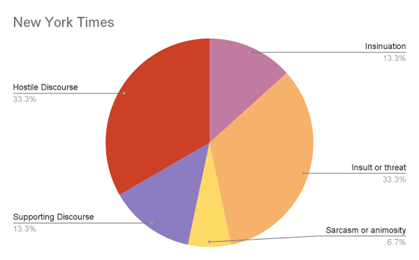

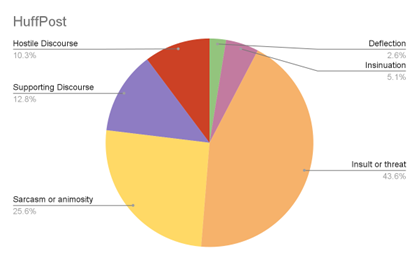

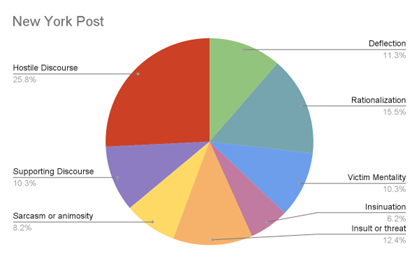

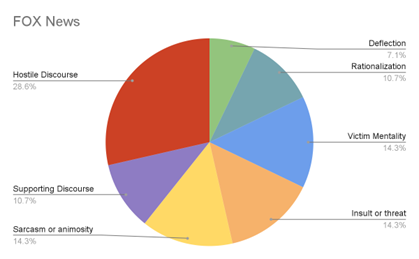

Introduction Have you recently read a comment section that looks more like a war zone and wondered: how did we get here? In our research project, we analyzed news headlines and comments trying to find the source, and we may have part of the answer. Digital tools for political discourse are becoming increasingly popular, and we wanted to better understand how framing influences political cognition and produces the political polarization we see in comment sections today. With this goal in mind, our project explores how framing in news headlines influences reader responses in the comments. Issue framing is when an author uses certain language to subtly present their opinion on a topic, and this can appear in anything from word choice to using passive voice to minimize someone’s culpability in an event. A single event or person can be presented in many different ways, and each of those ways could influence the reader into having a different opinion on the same event (Wang 2024). We specifically focus on party framing, which is when a frame is endorsed by a particular political party; this is extremely influential in the public’s formation of opinions — even more so than regular framing techniques. People will even dismiss a certain opinion just because it comes from the opposing party (Slothuus and de Vreese 2010). We hypothesize that framing in headlines can provoke emotionally-charged comments, with more negative and extreme headlines resulting in more hostility towards members of the opposing party. Methods We first analyzed six headlines from news sites of varying political affiliations, focusing on articles about Michael Cohen’s testimony in Donald Trump’s trial. As a control group, we first looked at headlines from PBS NewsHour and The Associated Press, which are perceived as more neutral news sources (Knight Foundation, 2018). Our two left-leaning news sites were The New York Times and HuffPost, and our right-leaning sites were Fox News and the New York Post (AllSides Technologies, 2024). To analyze these headlines, we looked into their uses of framing in their word choice and sentence structure and how these were used to assign blame and express the sites’ own opinions on Trump and Cohen. After analyzing the headlines, we turned to the comment sections from the left- and right-leaning sources. The neutral sources did not have attached comment sections, and we felt that they served us best remaining as the control from which to compare our other headlines. In analyzing the comment sections, our goal was to see if there was a connection between negativity and framing in the headlines and patterns of hostility and rudeness in the comments. This method limited our options, with many potential news sources pay walling their comment sections or simply not including them at all. Despite the fact that most comments are made on social media (Stroud et al. 2016), we preferred to avoid social media comments, as we felt that they would likely be less genuine and more filled with trolls and “bots.” In order to best organize our analysis, we compiled the most popular comments from each source, and then we compared them to each other to find shared patterns. We built a categorization system, shown in Fig. 11, that best captures the nuance of each comment section in comparison to the others so as to make for better comparison and more accurate connections to the headlines. Results and Analysis Our results from our initial analysis of each news headline showed variations in the framing of characters, actions, and descriptions involved in the news story, dependent on each news site’s lexical and syntactic choices. We observed that, despite these variations, each news site’s framing generally reflected their established political bias. For example, the syntactic choices in framing Cohen’s character varies greatly between Fig. 6, which refers to Cohen as an “ex-con”, and Fig.1, which refers to Cohen by name. These choices aligned with the political bias of each news site, thereby demonstrating a consistent correlation between the linguistic framing of each headline and political bias of each site. AP’s headline was a bit more left-leaning than expected, but it was later reposted on HuffPost, proving their left-leaning bias. The New York Times does not mention Trump by name, but it reminds readers of the power Trump once possessed as president by mentioning the Oval Office. The “hush” of “hush money” creates a negative moral judgment against Trump, but overall, this is one of the more neutral headlines. HuffPost frames Trump as an object of ridicule in this headline, granting Cohen power over him. Interestingly, it focuses on a more “gossip” style of reporting rather than things relevant to the trial. The focus on berating Trump makes this headline very biased. The Associated Press features a vaguely left-leaning headline. Cohen is granted credibility with connotations of celebrity, intrigue, and duplicity. There is a clear negative morality judgment against Trump in calling it a “scheme” instead of a “trial.” This PBS NewsHour headline is the most neutral of the six. They use an actual quote from Cohen, focusing on the facts. The Fox News headline frames Cohen as bumbling and spiteful. Trump becomes a victim of a hateful Cohen in this frame, creating sympathy for Trump and a distrust in Cohen. The New York Post frames Cohen as untrustworthy by describing him as an “ex-con.” Trump is a clear victim in this version of events. The headline also implies that Cohen is dredging up “old” events to ruin Trump’s 2024 campaign. Following this, we observed the top comments received by each article with a particular focus on keywords responding to the framing effects of the headline. Firstly, we observed a larger frequency of comments about Trump, the trial, and the general political situation, rather than of Cohen and his testimony. As predicted in our hypothesis, the more polarized headlines had more drastic and emotion-filled comments than the more neutral headlines. Both political sides were firm in their stance, unwilling to budge and change their perspective, with comments typically made to degrade or vilify the other side. Using keywords and notes from our initial observations, we identified eight key categories of comment-types which reflected similar biases that we observed from our headline analysis (Fig. 11). We created a color-coding system for analyzing our top comments according to these categories to measure the frequency of each category within each news sites’ comment section. As we hypothesized, hostile discourse, sarcasm and animosity, and insult or threat against the opposing party were consistently apparent across all four sources. However, we observed variations between left- and right-leaning discourse styles between both comment sections, and these are potentially related to the framing of each corresponding headline. These two comment analyses below demonstrate this difference in discourse style: We believe that these differences are potentially related to each party’s political and moral ideologies, which were reinforced by each headline’s framing. For example, higher frequencies of deflection and victim mentality among right-leaning comments might reflect defensive language in response to Trump’s victimization in right-leaning headlines and Trump’s vilification in left-leaning headlines. As shown in Figs. 7 and 8, we observed that hostile discourse, insult or threat, and sarcasm or animosity had the highest measure of frequency in our left-leaning sources. Figs. 9 and 10 show that hostile discourse, victim mentality, rationalization, and insult or threat had the highest measure of frequency in both our right-leaning sources. Interestingly, we also observed that supporting discourse was present in both sides, particularly in responding to others’ comments to reinforce their political beliefs. We believe that these findings show potential consequences for politically biased news headline framing that are manifested in comment sections by the reinforcement of certain political ideologies and antagonization of opposing parties, creating a sort of “echo chamber.” The New York Times comments tend to focus on the insinuation of Republican corruption. The comments were mainly directed towards Trump, attacking and vilifying him. When Cohen was mentioned, it was typically a positive association or connotation. Comments appeared heavily moderated, or perhaps the more neutral headline resulted in less intense comments. The HuffPost had less serious comments heavily filled with sarcasm, mockery, and insults towards Trump. With almost no mention of Cohen, the comments were mainly full of mocking and taunting remarks, with few attempted claims of substance. The New York Post focuses mainly on the content of the article, with strong remarks that the trial was set up by immoral Democrats. With the victimization and support of Trump, Cohen is framed as a devious liar who cannot be trusted. The Fox News comments had a mixture of the victimization of Trump and framing Cohen as an incompetent liar. The commenters also had a strong belief that the trial was fraudulent and biased. Discussion and Conclusions Our findings suggest that political framing in headlines through lexical and syntactic choices does create biased responses across the political spectrum. With political polarization in media becoming increasingly prevalent, especially considering 2024 is an election year, our findings are very relevant to discussions around the impact of media on public opinion and discourse. For instance, we found that headlines considered to be more neutral, such as the New York Times, resulted in less discourse between political parties, specifically with less engagement from the right, and the more biased headlines resulted in more hostile rhetoric and discourse in the comment sections between members of opposing parties. Therefore, our findings suggest that headlines that are considered to be more biased provoke stronger, more polarized discourse. Given that our study was limited by factors such as comment moderation and paywalls, a more comprehensive study might include social media responses or a broader range of politically-affiliated news sites rather than just the six we analyzed. For future research, we believe that our ideas can be expanded into a larger study using emerging AI models to analyze larger datasets from social media, which would yield more conclusive results. Perhaps they could detect bots and trolls on social media as well, removing that from consideration. The next time you are scrolling through the comment section on a political piece, take a moment to recognize what might cause strong feelings one way or another and how that is really affecting your perception of current events. With the tools presented, you now might be able to understand why there is so much fighting in the comment section. References AllSides Technologies. (2024). AllSides Media Bias Chart. AllSides. https://www.allsides.com/media-bias/media-bias-chart. Baratta, A. M. (2008). Revealing stance through passive voice. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(7), 1406-1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.010. Boydstun, A. E., Gross, J. H., Resnik, P., & Smith, N. A. (2013). Identifying Media Frames and Frame Dynamics Within and Across Policy Issues. New Directions in Analyzing Text as Data, 27-28. https://faculty.washington.edu/jwilker/559/frames-2013.pdf. Gligorić, K., Lifchits, G., West, R., & Anderson, A. (2021). Linguistic effects on news headline success: Evidence from thousands of online field experiments (Registered Report Protocol). PLOS ONE, 16(9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257091. Knight Foundation. (2018). Perceived accuracy and bias in the news media. Gallup. https://knightfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/KnightFoundation_AccuracyandBias_Report_FINAL.pdf. Slothuus, R., & de Vreese, C. H. (2010). Political Parties, Motivated Reasoning, and Issue Framing Effects. The Journal of Politics, 72(3), 630–645. https://doi.org/10.1017/s002238161000006x. Stroud, N. J., Van Duyn, E., & Peacock, C. (2016). Engaging News Project: News Commenters and News Comment Readers. Center for Media Engagement, Moody College of Communication, University of Texas at Austin. https://mediaengagement.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ENP-News-Commenters-and-Comment-Readers1.pdf. Wang, H. (2024). Linguistic Analysis of News Title Strategies in Media Frame—A Case Study of ‘The Mueller Investigation’ in the News Titles of The New York Times and Fox News. Journalism and Media, 5(1), 342-358. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5010023. Zhou, Z. (2022). Discourse Analysis: Media Bias and Linguistic Patterns on News Reports. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities, 637, 271-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.220131.049.