Hannah Shin, Emily Matsuda, Cindy Xiaoxuan Wang

The idea of femininity is often grounded to common elements such as being tender, sweet, and obedient (Lee et al., 2002). This study aimed to test the relationship between one’s level of pitch and the aforementioned characteristics– specifically the role of East Asian media in promoting gender stereotypes through the implementation of various pitch levels. In order to address this question, we conducted a pitch analysis of female fictional characters in popular East Asian shows by obtaining the average fundamental frequency of a speech string through Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2023). Unlike the hypothesis that higher pitch would correlate with the character’s degree of femininity, we found no significant difference in the average F0 value of stereotypically “feminine” and stereotypically “masculine” female characters. This finding suggests that pitch level alone does not override other non-linguistic and linguistic factors that altogether contribute to the perception of a “feminine” persona.

Introduction and Background

One’s style of speech serves as a unique indicator of their personality, gender, mood, age, and perhaps even their occupation. Even if we were to talk to someone over the phone, we would be able to learn a lot about the speaker’s identity due to this tight connection between speech and persona. This made us ask the question of: to what extent does one’s pitch level correspond to the speaker’s personality and perceived femininity? By analyzing fictional female characters in East Asian media, we attempted to identify the role that pitch level plays in reinforcing or rejecting gender stereotypes.

It is important to note that the average pitch level of East Asian females tends to differ from Western populations— hence the reason why we made within-group speech comparisons. For instance, Japanese women have higher pitches than Dutch women due to “the association of high pitch with attributes of physical and psychological powerlessness in the Dutch and Japanese cultures” (Van, 1995, p. 253). Additionally, Van (1995) reported that women with higher pitch are idealized and preferred by the general public in Japan, as high pitch level is correlated with many favorable social characteristics (Klofstad et al., 2012).

In East Asian culture, femininity is often associated with characteristics such as: being tender, sweet, obedient, and careful, while masculinity is described as having leadership, being confident, brave, ambitious, independent, and physically strong (Lee et al., 2002). For instance, characters designed to be “traditionally feminine” will exhibit submissive qualities as mentioned above, and pitch level may be adjusted to highlight their identities (Collins, 2011). We therefore hypothesized that female characters with a stereotypic “feminine” personality would produce higher pitch speech sounds on average than female characters who are depicted to be less “feminine.”

Although previous studies have revealed that sociocultural factors lead to a discrepancy between the speech of East Asian women and Western women, and a preference for high pitch in general, not many studies specifically investigate the role of East Asian media —specifically with regards to the use of specific linguistic styles in character portrayal— in perpetuating corresponding gender stereotypes. That is why our study aimed to address the significance of a female character’s speech style in East Asian media.

Methodology

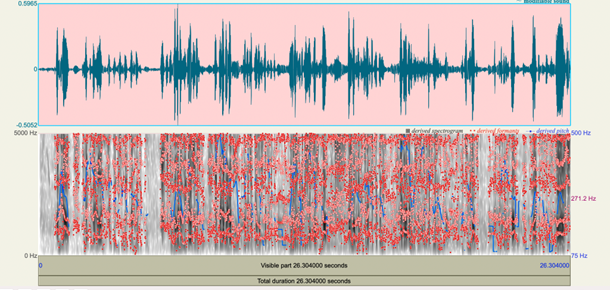

To examine the variations of pitch levels among female characters in East Asian media, we conducted a quantitative analysis on the data obtained from audio clips, with the help of Praat. Specifically, two polarizing female characters were chosen from each of the following shows from different East Asian countries: iPartment (Chinese), Shitsuren Chocolatier (Japanese), and Secret Garden (Korean), leading to a total sample of 6 characters. Comparatively “feminine” and “masculine” characters were selected based on the aforementioned characteristics of masculinity and femininity (Lee et al., 2002). For each character, we obtained a 30-second continuous speech sample during a neutral conversation to avoid any highly emotional conversations, such as arguments and crying scenes. We utilized Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2023) to measure the average, maximum, and minimum F0 levels of each character’s speech samples (Figure 1). We then compared our data and conducted an independent t-test (Table 2) to examine if the results of the comparison of average pitch levels for “feminine” vs “masculine” female characters were significantly different– indicated by a p-value of 0.05 or lower.

Results and Analysis

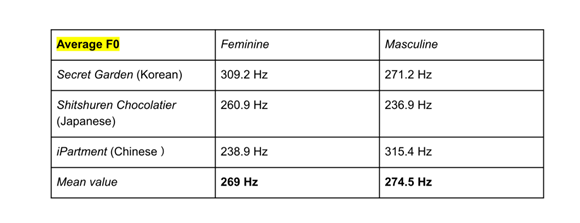

With respect to within-group comparisons, the Korean TV show Secret Garden showed results consistent with our hypothesis. The traditionally “feminine” character Ah-Young had an average F0 of 309.2 hertz, while the “masculine” character had an average F0 value of 271.2 hertz. Thus, the average F0 values obtained from this TV show provided positive evidence for our initial hypothesis that high pitch largely contributes to formulating a traditionally feminine persona. It is also important to note that the maximum and minimum F0 values possessed by the Korean feminine characters were highly similar, with the numerical difference between their maximum F0 values only being 19.8 Hz, and their minimum F0 values only differing by 4.5 Hz.

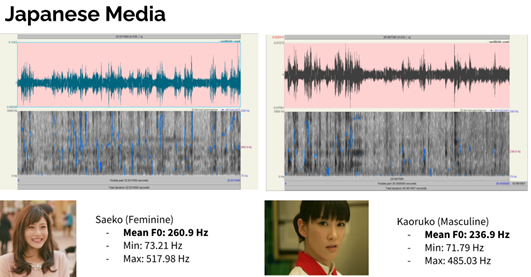

For the Japanese TV show, the stereotypically “feminine” character also had a higher average pitch than the “masculine” counterpart. Saeko, the traditionally “girly” female lead, had a mean F0 of 260.9 Hz while Kaoruko had an average pitch of 236.9 Hz. The two characters’ minimum and maximum pitch values highly aligned with one another as well, with the difference between their maximum values being 32.95 Hz and the difference between their minimum values being only 1.42 Hz. Such closely overlapping values in the minimum and maximum pitch range throughout the speech sample indicate that despite differences in average pitch level, people utilize their whole vocal range during regular day-to-day speech.

Although the data from the Korean and Japanese shows were in favor of our hypothesis, the Chinese show, iPartment, demonstrates results that suggested otherwise. The masculine character surprisingly exhibited a higher average pitch throughout her speech; specifically, the mean F0 value for the masculine character YiFei was 315.4 Hz, which is considered to be conventionally high. In comparison, the feminine character, Nuolan, had a lower average F0 of 236.9 Hz, which was significantly lower than the F0 of YiFei.

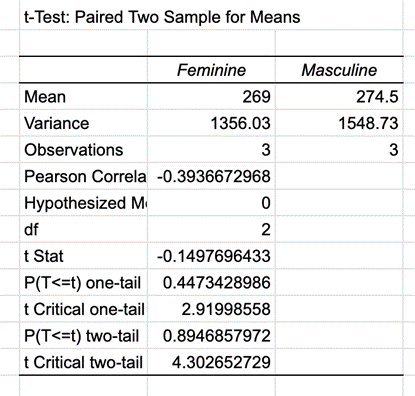

Lastly, in order to test for the statistical significance for any observed pitch differences, we conducted an independent t-test of the average value of the feminine and masculine characters’ pitch levels. The average pitch level of all stereotypically “feminine” characters was 269 Hz, while the average pitch level for the stereotypically “masculine” characters came out to 274.5 Hz. The t-test suggested that there was no statistically significant difference between these two values, as the p-value came out to p= 0.45. These findings, therefore, were insufficient in leading us to accept the initial hypothesis that the average pitch level of female characters plays a critical role in portraying a stereotypically feminine, girly persona in East Asian media.

Discussion and Conclusion

The sample as a whole did not support the hypothesis, as the average pitch level did not significantly differ between feminine and masculine female characters. Although we were able to observe within-group differences for the South Korean and Japanese media, we were unable to identify the predicted pattern of higher pitch in feminine characters within the Chinese drama. This suggests that pitch isn’t the only factor that contributes to one’s feminine persona– there are possible non-linguistic factors, such as appearance (ex. short hair, fashion), occupation, etc. in play that interact to achieve specific characteristics in the media. For instance, other non-linguistic similarities found within the feminine characters was their similar sense of fashion. They dressed themselves in softer colors, more feminine accessories, and wore more skirts and dresses compared to the masculine characters who had a more gender-neutral haircut, dressed in darker clothing, and largely wore pants. It is also important to note that the “masculine” female character in Secret Garden had a nontraditional occupation as a stuntwoman. Her role as a stuntwoman displayed characteristics that were previously identified as being primarily masculine: brave, ambitious, independent, and physically strong (Lee et al., 2002), which could have been a more salient factor in the portrayal of gender norms.

Additionally, it is highly likely that the impressions of masculinity and femininity differ between the three East Asian countries. Although East Asian countries may share common values and practices, there are several invariants: one of them is the link between gender norms and education level. In particular, Chinese culture often correlates masculinity with the possession of a PhD degree (Shanghai Star, 2005). In China, even a third gender type besides men and women has been proposed specifically for females with a PhD degree– this is due to the traditional belief that women are physically and mentally weaker than men, which results in unequal perceptions behind the cognitive capabilities of men and women. In comparison, such prejudiced thoughts regarding gender stereotypes and education are not as prominent in Japan and Korea. This finding above suggests that there are subtle differences in gender beliefs within East Asian culture, which might contribute to why we were not able to observe a static trend in the linguistic style of feminine female characters in media.

Other linguistic factors that contribute to one’s persona could be the speaker’s word-choice, pitch contour, etc.– specifically in the Korean drama Secret Garden, the feminine female lead Ah-Young would often include a word-final nasal sound “ㅇ” that is associated with a playful, cute tone in Korean culture. For instance, she would add the “ㅇ” sound to the end of a neutral phrase “그랬어?” [kɨlɛs͈ʌ], creating an ungrammatical yet stylistic production “그랬엉?” [kɨlɛs͈ʌŋ]. Comparatively, the masculine female lead Ra-Im spoke in a more strict, direct, blunt tone throughout the drama, with the absence of a word-final nasal sound.

Some limitations of this study include the possibility of interference from background noise and thus an inconsistency in speech sample quality. Also, the speech samples were rather short, which might be insufficient in catering to all the variations in the stories’ settings and changes in characters’ personalities and corresponding degrees of femininity (if any occurred). In the future, the research could be improved by including an analysis of several media sources within one culture, instead of one representative film. Additionally, a longer speech sample that encodes the pitch variance throughout the entirety of the drama would lead to a more accurate analysis. Lastly, the speech sample could be cleaned up to minimize “noise.” This could be achieved by feeding the audio clip through a software that isolates linguistic sounds (aka speech sounds) with nonlinguistic ones, or by adjusting the level of the background noise on a higher-quality audio file.

Throughout this research, we heavily emphasized how the use of pitch levels is relevant in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean media to portray both feminine and masculine characteristics. However, it is important to note that a particular language is spoken differently depending on which linguistic community the speaker belongs to within a single country as well. For instance, an existing article regarding the pitch levels of female speech in two different Chinese villages — Jiuying Village and Taoyuan Village — explores how a specific language can be utilized and spoken differently depending on which linguistic community the speaker belongs to (Deutsch et al., 2009). Moreover, it was concluded by the authors that “the overall pitch level of a speaker’s voice is influenced by a mental representation that is acquired through exposure to the speech of others” (Deutsch et al., 2009), indicating that the speaker’s experience and lifestyle in a specific linguistic community affects their tones and pitches in the long run. For future research, focusing on a specific language and comparing how that language is spoken differently in various linguistic communities (hence the emergence and progression of regional dialects) may be beneficial for in depth analysis of a specific language.

It is also plausible that women’s voices are gradually getting deeper overall. The article published by BBC explores how social transformation is mirrored to our speech style, “women today speak at a deeper pitch than their mothers or grandmothers would have done, thanks to changing power dynamics between men and women.” (Robson, 2022). Since the expectations and social norms are changing over time, it is reasonable that our speech style is adjusting to them. To extend upon this research, we could investigate recent shows (past 5 years) from East Asian countries, as our focused media was relatively old and failed to capture the social norms in today’s society.

Altogether, this study revealed that our speech style and persona potentially have a bi-directional relationship, especially with the strong presence of the media in our day to day lives. It allowed us to consider the broad questions of: “What makes us perceive a certain character as feminine versus masculine? Could this factor potentially be linguistic in nature?” Despite not obtaining significant cross-cultural findings, the research uncovered a possibility of Korean and Japanese media implementing high pitch to portray femininity, and the potential for future research that reflect each country’s distinct position surrounding the notion of gender and in-depth analysis of the role of regional dialects in shaping persona.

References

Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2023). Praat: doing phonetics by computer [Computer program]. Version 6.3.10, retrieved 3 May 2023 from http://www.praat.org/

Collins, R. L. (2011). Content analysis of gender roles in media: Where are we now and where should we go? Sex Roles, 64(3-4), 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9929-5

Deutsch, D., Le, J., Shen, J., & Henthorn, T. (2009). The pitch levels of female speech in two Chinese villages. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 125(5). https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3113892

Klofstad, C. A., Anderson, R. C., & Peters, S. (2012). Sounds like a winner: Voice pitch influences perception of leadership capacity in both men and women. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1738), 2698–2704. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0311

Krahé, B., & Papakonstantinou, L. (2019). Speaking like a man: Women’s pitch as a cue for gender stereotyping. Sex Roles, 82(1-2), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01041-z

Lee, B. S., Kim, M. A., & Koh, H. J. (2002). Development of Korean gender role identity inventory. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 32(3), 373-383. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2002.32.3.373

Robson, D. (2022, February 25). The reasons why women’s voices are deeper today. BBC Worklife. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20180612-the-reasons-why-womens-voices-are-deeper-today

Shanghai Star. (2005, March 4). Women PhDs the 3rd type of people besides men, women? China Daily. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-03/04/content_421834.htm

van Bezooijen, R. (1995). Sociocultural aspects of pitch differences between Japanese and Dutch women. Language and Speech, 38(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/002383099503800303