Camille Lanese, Chang Liu, Heather Pritchard, Merton Ung, Tracy Zeng

If you were to go on TikTok right now, one word might stand out to you: “periodt.” With a hashtag including more than 632 million views and endless videos with teenagers exclaiming “and that’s on periodt!”, you might wonder what is up with this word. In our study we examined exactly who is using the term “periodt” and when they are using it. Through surveying college-aged students, we examined if factors such as gender identity and sexual orientation affected whether or not TikTok users used the term “periodt” online or in their daily lives. After looking through the results, we concluded that gender identity and sexual orientation seemed to affect whether TikTok user knew of the word “periodt,” but had no impact on when they used the term. Overall, most participants were most comfortable using the term online, and were extremely uncomfortable with the idea of using “periodt” in a professional setting. In the future we aim to further examine the origins of “periodt” and how people acquire it as a word.

Introduction

TikToks are vertically filmed videos 6-60 seconds long. TikTokers play off various viral trends with repeated phrases and terms, and introduce new lexical items into users’ everyday speech. Importantly, users comment on others’ TikToks and share TikToks on other social media platforms. Also of note, TikTok users will write specific hashtags in their captions to make their videos appear on the “For You page”, the place where TikTok users discover new videos. Due to a combination of the users comments, hashtags, and sharing it is common for new words to become extremely viral through widespread use. TikTok’s powerful influence is reflected by the fact that the social media platform has over 800 million users worldwide. Thus, TikTok forms a kind of speech community with jargon through interaction between speakers. We analyzed college-aged students’ usage of the TikTok lexical item “periodt”, used to emphasize a point or signal the end of a discussion. We hope to answer, does a speaker’s gender identity and/or sexual orientation affect whether they adopt TikTok terms into real-life social interactions?

Background

The field of sociolinguistics understands linguistic variation as an “essential feature of language” through which speakers “index” aspects of their identity (Eckert 2012: 94). Specifically, gender is performance, in which speakers use linguistic features to construct and reinscribe their gender for their audience (Butler 1990: 179). For the older 18+ TikTok population, which includes our target population, using TikTok language requires more speaker agency because TikTok is not the norm, and thus TikTok language indexes aspects of identity for these speakers. Holloway and Valentine (2014) show that a teenager’s identity can become a mixture of their online and offline influences, since teenagers perceive both their online and offline identities as real spaces. Based on the studies by Eckert and Butler we see that a person’s identity is reflected in their lexicon. Our study seeks to examine whether the influence of the online spaces of TikTok will be reflected in our participant’s lexicons. Podesva (2011) analyzed the Californian vowel-shift for one LGBTQIA+ speaker and demonstrates that speakers use phonological features to index their identity. Podseva focuses on speech acoustics in various social settings. Our study is different from this in the way that we are examining our participant’s lexicons, and in the way that we are analyzing a large number of people rather than one person. The study that was most similar to ours was Banman’s (2014) which analyzed Tweets by men and women and compared gender markers such as pronouns. Banman et. al found that there are lexical items strongly associated with each gender. Our study is similar because we also seek to examine the lexical differences between gender, but also different because we are also examining their sexual orientation. To learn more about gender and other demographics in social media, check out this TED Talk by Johanna Blakley.

Methods

We collected data from 100-200 American college students (aged 18-22) through an online survey with questions about usage of TikTok lexical items as well as gender and sexual orientation. Our preliminary hypothesis was that members of the LGBTQIA+ community are more likely to know and actively use TikTok language, since many TikTok terms are associated with said community. We also hypothesized that self-identified females are more likely to use TikTok terms, because of TikTok’s origins in Musical.ly and because self-identified females are usually the pioneers of new lexical items. The word that we chose to analyze was “periodt”, since it is a word that not only has roots in the LGBTQIA+ community, but was also popularized through TikTok by the use of hashtags and viral audios used in various videos. If you’re interested, check out this TED Talk by Dao Nguyen that discusses what kinds of videos and topics go viral.

Results

We received 109 total responses. Of those, we received 80 female responses, 26 male responses, and 3 nonbinary responses. Although our percentage of female responses was disproportionate, we still found that a far greater majority of female respondents were familiar with the term.

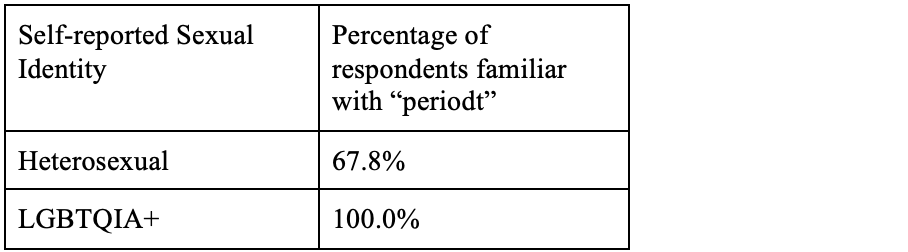

Similarly, according to our hypothesis, when sorted by self-reported sexual identity, all of our LGBTQIA+ respondents were familiar with the term, while a smaller percentage of our heterosexual respondents were familiar with the term. At the same time, we are aware that there is further diversity within the queer community, so analyzing the entire LGBTQIA+ community as one homogenous section does weaken our analysis.

Regardless of gender identity and sexual orientation, overall, the participants feel the most comfortable using the term “periodt” online with their peers, a little less comfortable when using it face-to-face with peers, and almost equally uncomfortable when using it online and face-to-face with a professor/boss. When using the term with peers, female and non-binary participants feel slightly more comfortable when using it online than using it face-to-face. From our data, male LGBTQIA+ participants clearly feel more comfortable than other groups when using the term “periodt” with their peers online and face-to-face, and slightly more comfortable when using it with a professor/boss online. But since only 2 LGBTQIA+ male participants responded, we cannot confirm that this pattern applies to most people with this gender identity and sexual orientation. Also based on the results we received, non-binary participants feel less comfortable than other groups when using the term with their peers online and face-to-face. But since only 3 non-binary participants responded, we cannot confirm that this pattern applies to most people with this gender identity and sexual orientation.

Discussion and conclusions

Based on our results, we conclude that gender identity and sexual orientation seems to affect the familiarity with newly-emerged TikTok terms, but have little effect on the usage of those terms in both online and in-person settings. We collected data on many factors that we didn’t have the time or space to explore, such as participants’ native languages and hometowns. We also asked participants which other TikTok terms they were familiar with, which in the future could be helpful to contextualize “periodt” among other TikTok lexical items. An additional factor that we didn’t have the space to explore was race. Although the word “periodt” originates from the African American community, we did not analyze whether our participant’s knowledge of the word could originate from their racial backgrounds. The final shortcoming of our study was our lack of LGBTQIA+ participants. In an ideal study, our study would have equal amounts of participants for every subdivision we analyzed, especially for the male LGBTQIA+ participants.

In further studies, we would be interested in correlating time spent on TikTok with comfort using the word. Then, we would analyze whether time spent on the app factors more into TikTok term usage than gender or sexual identity (Holloway and Valentine, 2014). A similar study could also be performed on other words that have become popular with AAVE and LGBTQIA+ roots, like “shady, tea, sis”, but on platforms like YouTube or Twitter. Also of interest, how do people, especially non-binary and LGBTQIA+ groups, acquire TikTok terms? Our study asked whether the participants knew the word, but not whether the participants learned the word from TikTok. A few more specific questions to investigate include: Is there a difference in the usage between talking with close friends and classmates? Is there a difference when talking with the same group of people, but about different topics?

Our study regarding the term “periodt” is also important for broader research and issues. The large number of participants using “periodt” despite not knowing the origins of the word is emblematic of the larger issue of erasure in western society. Despite the fact that “periodt” has its origin from AAVE, the word was co-opted by the LGBTQIA+ community during the late 1960s. “Periodt” was then popularized in mainstream culture as a word that indexes LGBTQIA+ membership, since it was popularized by shows like Rupaul’s Drag Race, Queer eye, and various YouTube content creators. Prior to TikTok, “periodt” was only popular within the LGBTQIA+ and African American communities. After “periodt” was popularized on TikTok through famous audios, and hashtags, the word had become viral and it was no longer used exclusively by the queer and African American communities. Our study shows an abundance of users who use “periodt” without actually knowing the origin of the word. Other viral phrases that were created by the black community and was co-opted by the LGBTQIA+ along with “periodt” that do not have their origins widely acknowledged would be “spill the tea, sis, yas, queen, shady”. Acknowledgement of the origins of “periodt” is important because of the U.S. erasure of black and queer history.

References

Bamman, David, et al. “Gender Identity and Lexical Variation in Social Media.” Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 18, no. 2, 2014, pp. 135–160., doi:10.1111/josl.12080.

Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge

Eckert, P. (2012). Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41, 87-100.

Holloway, Sarah, and Gill Valentine. “Cyberkids? Exploring Children’s Identities and Social Networks in On-Line and Off-Line Worlds.” 2014, doi:10.4324/9781315011257.

Kulkarni, Vivek, and William Yang Wang. “TFW, DamnGina, Juvie, and Hotsie-Totsie: On the Linguistic and Social Aspects of Internet Slang.” 22 Dec. 2017.

Podesva, R. (2011). The California vowel shift and gay identity. American Speech, 86(1), 32-51