Karin Antablian, Leslie Cheng, Tabitha Haskins, Kaoru Kaburagi, anonymous author.

This study is an investigation of the relationship between biracial individuals and their association or dissociation with their cultural heritage. Using monoracial individuals as a control, we utilize survey methods and metalinguistic interviews to expand upon Cheng and Lee’s (2009) model, focusing particularly on how language attitudes and heritage language maintenance influence biracial identity indexation. In doing so, our purpose is twofold. First, we aim to establish what connections exist between attitudes towards heritage language learning and language maintenance. Second, we aim to better understand how language maintenance affects biracial identity. We found that while monoracial and biracial individuals both have positive perceptions of heritage language learning, these attitudes tend to be stronger among monoracial individuals. Additionally, we found that cultural identity was more turbulent among biracial individuals, but that they were more likely to perceive heritage language maintenance as a way to assert and connect with their multicultural heritage.

Introduction and Background

The United States is becoming an increasingly multiracial, multilingual nation. While still constituting a relatively small portion of the population, people of mixed race make up the fastest growing demographic in America – in the past decade alone, the multiracial population within the United States has increased by 276 percent, from 9 million people in 2010 to 33.8 million people in 2020. Furthermore, since 1980, the number of people who speak a language other than English at home has more than doubled (US Census Bureau, 2020). In light of these changing demographics, research surrounding biracial identity and attitudes towards bilingualism is becoming particularly paramount.

In crossing over cultural boundaries and racial lines, biracial individuals exist at the crossroads of disparate backgrounds that at times may be at odds with one another. Existing within this liminal space “in between,” so to speak, can contribute to the formation of a “marginal” identity, feelings of conflict when negotiating identity (Poston, 1990), or distance from their cultural heritage (Bracey, Bámaca, & Umaña-Taylor, 2004).

However, it is understood that when an individual perceives facets of their identity to be compatible, the individual’s sense of self becomes more unified, a process known as identity integration (Syed & McLean, 2016). Models of identity integration have been applied to examine the process of biracial identity negotiation in various domains. One framework of particular interest comes from Cheng and Lee (2009), who present four methods of identity indexation among those of biracial descent. These classifications represent how the individual navigates their cultural identity in society, and also serve as an indicator for the degree of conflict or turbulence that the individual has over their own identity. The classifications are as follows:

- Intersections: Identification with individuals of related groups

- Dominance: Identification with individuals of one primary group

- Compartmentalization: Identification with a group is situationally dependent

- Merger: Simultaneous, cross-group identifications

The present study applies Cheng and Lee’s framework to investigate the relationship between biracial individuals and their association or dissociation with their cultural identity. More specifically, we look at the role of heritage language maintenance in informing the stances and alignments of biracial individuals. Following the conclusions of Lee (2002), which suggests strong correlations between an individual’s heritage language proficiency and their cultural identity, there exists the question of whether dual language use within the home generates a hyper-salient cultural identity — or an aversion towards particular cultural indexations.

Using monoracial students as a point of reference, we hypothesized that biracial students may exhibit more conflicted, turbulent attitudes or be more ambivalent towards bilingualism due to parents of differing cultural backgrounds, which would be reflected in how they culturally identify themselves. We also hypothesized that monoracial students may be more inclined to learn the heritage language, as both parents are likely to show a unified attitude towards bilingualism and thus exhibit less cultural conflict.

Methods

We utilized survey methods and metalinguistic interviews to collect data. In total, we surveyed 32 college students and interviewed 9 college students. Out of those that we surveyed, 27 participants were of monoracial descent and 5 participants were biracial descent. 5 interviewees were of monoracial descent and 4 interviewees were of biracial descent. While participants came from a variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds, the majority came from Asian backgrounds (n=26). All biracial participants were half white.

Our survey contained two sections. In the first section, we asked participants questions about their language demographic background information (e.g., What is your primary language? If you speak another language at home please list them.) We also asked whether they belong to a cultural community and/or they grew up in one. In the second section, participants ranked their agreements on a scale of 1-5 with a series of statements. Statements concerned both parents’ attitudes towards bilingualism (e.g., My parent thinks it’s important I learn another language.) as well as their personal attitudes (e.g., If I ever have kids, I would want them to know a second language.)

After surveying participants, we conducted interviews to further investigate their experiences and possible differences in attitudes towards bilingualism between parental units, especially if the student is of biracial descent. During the interviews, we focused more on how biracial students indexed themselves and looked at possible connections to their linguistic backgrounds (e.g., “What were your caregivers’ attitudes towards your heritage language(s)? Were they supportive, against learning it? Did their attitudes change as you got older?”)

Results

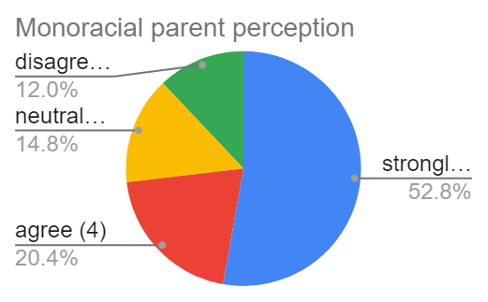

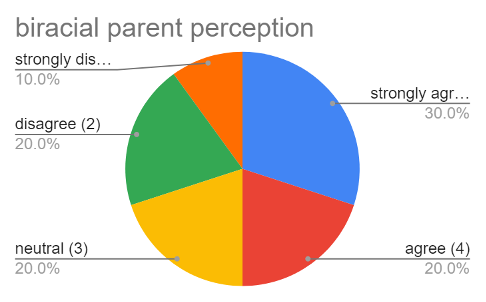

Unsurprisingly, both biracial and monoracial students had positive perceptions of bilingualism, and thought their parents had positive perceptions of bilingualism as well. However, these groups differed in how strong these positive perceptions were. Since the survey asked participants to rank how strongly they agreed with a series of positive and negative statements about bilingualism from a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), we were able to observe the distribution of their responses. Figure 1 below shows the distribution of responses of monoracial students and Figure 2 shows the distribution of responses for biracial students regarding how much the participants agreed that their parents have positive attitudes towards bilingualism.

Although both monoracial and biracial students thought their parents had generally positive views towards bilingualism, the monoracial students agreed more strongly than the biracial students. The monoracial students picked “strongly” agree over 50% of the time, whereas the biracial students only picked that 30% of the time. Monoracial students also agreed (ranking either 4 or 5) with the positive statements over 70% of the time whereas the biracial students only ranked the statements 4 or 5 50% of the time. Although this is merely a correlation, it is an interesting observation to note that could lead to more studies in the future.

For the interviews, there was variation across both monoracial and biracial students in how strongly their parents advocated for their learning in the heritage language. This is unsurprising given how each household is different and the variety of factors that shape parents’ decisions to teach the heritage language or not. Time may be an important factor, and the parents’ own fluency in the language may hinder or encourage this passing on of language to their children.

However, we did notice specifically that for biracial students who later chose to learn the heritage language on their own, they emphasized a want to connect to their heritage, especially since it gives a sort of “validity” to their cultural identities. Elaine, a half-Peruvian half-White student stated, “Once I started learning Spanish I had… more validity to my identity as a Peruvian because it’s like even though I didn’t look like it, well…I can speak in this language.” Biracial students appeared more questioning of their identities compared to monoracial students since they were not necessarily as exposed to their heritage culture and may feel more “outside” the culture due to their mixed appearance. They appeared to be more questioning of their own identities especially if they couldn’t speak the heritage language well, as language is often seen as a pillar of cultural identity.

On the other hand, the monoracial students we interviewed appeared to comfortably identify with the X-American label, for example Asian-American or Mexican-American. When asked about cultural identity, one student whose parents are first-generation Korean immigrants stated that she identifies as “just Korean-American” and “never really questioned it because [she] grew up in [a predominantly Asian area with a lot of other Koreans”. Presumably, she grew up in a household that was unified in culture and language, and people would not question her “Koreanness” based on her appearance. It is interesting to note that so-called “hyphenated” Americans have earned a spot in the mainstream social discourse of American society, yet biracial students have not necessarily done so due to the diversity in their parents’ heritages. A biracial identity is not easily constructed across all groups because there is such a mix of cultures.

Discussion

Overall, there were not drastic differences between the attitudes of the parents of monoracial individuals versus biracial individuals. There was a large degree of uniformity in the belief that being multilingual is a beneficial skill to have, albeit varying degrees of implementation. There were significant differences in the participants themselves, however. Among our monoracial survey population, we see that the majority of them informally acquired their heritage language and that the heritage language is the dominant language of the home. Among our biracial survey population, English is the predominant language at home, with only half of our participants having acquired their heritage language. With the exception of a single participant, the heritage language was formally acquired.

The most interesting difference between these two groups was that those of the biracial population exhibited a demonstrated awareness of their language indexation that monoracial individuals did not. One participant, Yukari, shares of how her Japanese mother passed down the Japanese language to her:

“When I was living in Japan, I honestly felt I was pretty privileged since the people around me were also half Japanese, but a lot of them didn’t know how to speak Japanese and so I had the sense of pride that ‘Oh, I can speak Japanese’ and I thought it was a good thing because I consider Japan my home, so being able to communicate with not only my family, but the community was a really important thing to me… If I wasn’t able to speak Japanese, I feel like I would’ve connected more to my American side of the family. I would’ve considered myself more as white instead of Japanese.”

Yukari’s experience, building off of the information presented by Elaine previously, allows us to draw parallels between these two participant’s experiences. Each biracial individual indicated a high level of indexation through their heritage language. Both Elaine and Yukari used their heritage language to make a claim to their non-white identity. Not only was this consciously done, but each of them used their heritage language to navigate social circumstances and interactions. Considering the point made by Cheng and Lee (2009) (see quote below), it is evident that in the increasingly multicultural, multilingual United States, more and more biracial individuals are operationalizing their heritage language to make claim to a multifaceted and multicultural identity.

“People change their identification strategies depending on individual constraints such as attention and cognitive resources, and contextual factors such as situational cues that make a particular social identity more or less salient.” (Cheng & Lee, 2009).

One limitation to our study was that the survey responses we collected were not evenly distributed between monoracial (n=27) and biracial students (n=5). Furthermore, we tried to keep our survey as simple and concise as possible, so we were limited in the number of questions we could ask. There’s only so much a survey can cover in terms of nuances in attitudes towards bilingualism. Lastly, even with our interviews, the participants tended to only talk about topics adjacent to our questions, so this was only the tip of the iceberg as well. We hope that despite these limitations, our study serves as a foundation to more discourse and research about biracial students, language use, and cultural identity in the future.

In conclusion, there was little to no significant variation between parents of monoracial and biracial individuals in perceptions of bilingualism. The greatest factor for heritage language acquisition was its presence, or lack thereof, in the home. Our research did provide evidence for cognizant identity indexation through heritage language acquisition on the part of the biracial individuals. This was in direct contrast to the motivations for heritage language use in monoracial individuals. Moving forwards, it would be beneficial to investigate ways that language is encouraged through the maternal line, as our data gave some implications for this. Our sample size, however, does not provide enough variation or control to determine the validity of this statement.

Additional Resources

This Ted Talk is given by two high school sophomores who talk about the experience of being biracial as well as some common misconceptions about biracial individuals. It’s a personal account of being biracial that also emphasizes the ways language can exclude people or deny their identities.

Check out this related Languaged Life blog post from a previous class to find out more about social factors that inform language maintenance within multilingual families!

References

Bracey, J.R., Bámaca, M.Y. & Umaña-Taylor, A.J (2004). Examining ethnic identity and self-Esteem among biracial and monoracial adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 33, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000013424.93635.68

Cheng, C., & Lee, F. (2009). Multiracial identity integration: Perceptions of conflict and distance among multiracial individuals. Journal of Social Issues, 65(1), 51-68. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.01587.x

Foster-Frau, S., Mellnik, T., Blanco, A. (2021, October 8). ‘We’re talking about a big, powerful phenomenon’: Multiracial Americans drive change. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/10/08/mixed-race-americans-increase-census/

Lee, J. (2002). The Korean language in America: The role of cultural identity in heritage language learning, language, culture and curriculum, 15(2), 117-133, DOI: 10.1080/07908310208666638

Poston, W. S. (1990). The biracial identity development model: A needed addition. Journal of Counseling & Development, 69(2), 152–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01477.x

Syed, M., McLean, K.C. (2015). Understanding identity integration: Theoretical, methodological, and applied Issues. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 109-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.09.005.

United States Census Bureau. (2022, March 25). 2020 Census illuminates racial and ethnic composition of the country. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html

United States Census Bureau. (2020). Populations and people. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/profile?g=0400000US06