Tina Festekdjian, Krunali Mehta, Mark Keosian, Tatiana Akopyan

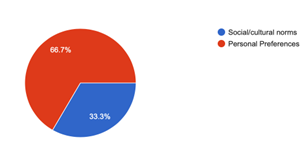

Do you ever wonder why people belonging to different cultures express love differently in their romantic relationships? Are they accustomed to verbal or nonverbal forms of affirmation, and does this carry on throughout generations? This study explores why and how second-generation college students living in Los Angeles who identify as Latin American, Asian American, or American verbally affirm their partners, as we were curious to see if culture may cause communicative differences in relationships. Whether words of affirmation can be attributed to the way people were raised, their cultural habits, or their personal preferences, the population we studied displayed an interesting trend: individuals are less heavily influenced by their culture, and the majority (66.7%) are more likely to follow their personal preferences when expressing love. While the minority (33.3%) displayed cultural allegiance, we generally noticed that one’s culture is not the leading contributor to how they express love – possibly due to the generational shift that embodies independence, socialization, and even Americanization. We can conclude that our target population is perhaps more open-minded, individualistic, and willing to break cultural barriers for love to embody their own preferences. Breaking barriers can make students more comfortable to approach others, adapt to new love languages, and better learn how to express love verbally.

Introduction and Background

Do second-generation college students living in Los Angeles prefer to follow cultural guidelines or personal preferences when expressing verbal love in romantic relationships?

We hypothesize that particular people will be influenced by their culture if they abide by cultural norms, but that this most likely does not separate people – especially in a younger generation of college students who may be more willing to branch out. The motivation for our research was to explore what role culture plays in verbal affirmation in romantic relationships for second-generation college students, and whether social norms, family life, or personal feelings are the leading contributors. The problem is, based on the way we were raised, or based on our own preferences, we show love differently, which can cause miscommunication. By investigating different forms of linguistic communication among Latin American, Asian American, and American college students in Los Angeles, we can deduce how intimacy is present through verbal communication in their relationships. Some specific aspects of communication that we will look at include words of affirmation, romanticism in conversations, tone, and context of affection. For example, in a cross-cultural context, this means: the specific words people use to address their partner and whether it comes from their own language/culture, if someone is more expressive verbally or uses nonverbal communication, and in what situations they will be verbally affectionate. Virtual communication like text-messaging will also be studied to develop a deeper understanding of day-to-day interactions and what exactly is said in these relationships. Above personal experience, relevant literature tells us what we know so far. Brinton (1886) displays how many tribal and modern languages of Latin America tie the sentiments of love to verbal expression. The Nauahtl and Aztec tongue, for example, indicate higher levels of emotional strength with words of origin that hold deeper meanings and cultural values. These lexical attributes can provide evidence as to why Latin America is the home to many “romance languages”. Lindholm (2006) explores the Western (American) vs. Eastern scope of view, delineating how Western linguistic expression is often romanticized in the media and verbal expression of gratitude and admiration is common. On the other hand, Bello et. al. (2010) provides evidence for how in some Asian cultures, communicative patterns like verbal affirmation are less likely to be expressed. Allendorf (2013) provides context on how romantic relationships have evolved from arranged marriages to love marriages in many parts of Asia. Ultimately, we were able to bridge this gap by bringing generational evolution to the table. Because our population is second-generation college students, and most of our literature is broadly culturally based, we were able to understand that the evidence for our trend generally lay in the people, rather than what cultural group they belong to. Being in college in Los Angeles leads to Americanization, socialization, and the added element of independence that our literature did not address.

Methods

Through the use of a clear and straightforward 4 question questionnaire and student-submitted text message screenshots, we gathered responses from 27 second-generation college students about which form of love expression they prefer to use when expressing love to a romantic partner, along with the social and cultural norms of love expression they are familiar with. Finally, we had the students answer whether they prefer to use their chosen personal preferences or the social and cultural norms they are familiar with when expressing love and affection to a romantic partner in order to see which influences students’ communication and verbal affirmation to a greater degree. These methods allowed us to analyze the specific words and tones being used by students to express affection to a partner, along with the conversational structures and atmosphere. We compared these results with the social and cultural norms of love expression the students responded they were familiar with in order to see if their personal preferences were or were not being influenced by social or cultural norms. While a student’s personal preference for verbal affirmation or love expression and the social and cultural norms they are familiar with may overlap, this may be attributed to strong cultural roots or identity. By looking at which words, verbal affirmations, and other forms of love expression second-generation college students preferred to use when expressing love or affection to their romantic partners, we hoped to find whether culture played a significant role in the specific words, affirmations, or actions being used by these students or whether the personal preferences these students have just simply outweigh the social and cultural norms in their lives.

Results and Analysis

In regards to our results from Table 1: Culture, we collected information from 3 different cultural groups: 37% being Latin American college students, 33.3% American college students and 29.6% Asian American. We collected a fairly good range of responses from our intended cultural groups to get a fair representation of second-generation college students.

When asked about their preference on personal preferences or social/cultural norms shown in Table 2: Norms, 66.7% chose personal preferences while 33.3% chose social/cultural norms.

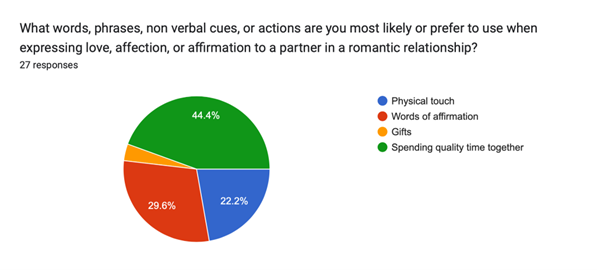

These students were then asked what words/actions were their preference in romantic relationships shown in Table 3: Preferences, from choices of spending quality time together (44.4%), words of affirmation (29.6%), physical touch (22.2%), and gifts (3.7%).

We were able to collect examples of text messages in Table 4: Cross Cultural Text Messages from each cultural group. We found Asian American college students to be showing love through using words like “shona” that embodies their cultural background where Latin American college students show love by saying thank you and words of appreciation. The difference we found in American college students shows love through constant repetition of words of affection and reassurance.

Discussion, Conclusion, and Contributions

Through conducting our research, we concluded that our findings are truly impactful as we found that college students are more likely to use their own personal preferences during verbal affirmation in a romantic relationship rather than their known social and cultural norms. This is important to recognize because it highlights that students aren’t restricted or limited by their cultural upbringing and actually care more about their own personal preferences when expressing verbal affirmation to a romantic partner. Another finding to recognize is the bias when students are asked if they follow social norms or their own personal preferences. They might not answer truthfully or not even realize that social norms have become their personal preference overtime. For generations to come, we may find that students have become more approachable or sociable as culture may not play as big of a role in verbal affirmation and love expression as we may thought. Ultimately, our findings could definitely benefit students who are in existing romantic relationships or are interested in finding a romantic partner as it can help break social barriers and make students more comfortable when communicating romantically and approaching those of different cultures. We were able to analyze various findings through code-switching from Hindi to English in the Asian American text message and how emotions/feelings are shown through the usage of emojis in online communication to further understand how society and cultural factors have contributed to various forms of communication. Although some students still prefer to follow their known social and cultural norms in verbal affirmation with a partner, our findings show that students are more open minded to adapting to one another’s love languages and potentially learning how to better communicate and express love verbally, as they are not being tightly confined by social and cultural norms.

References

Allendorf, K. (2013). Schemas of Marital Change: From Arranged Marriages to Eloping for Love. Journall of Marriage and Family, 75(2), 453–469. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23440792

Bello, Brandau-Brown, F. E., Zhang, S., & Ragsdale, J. D. (2010). Verbal and nonverbal methods for expressing appreciation in friendships and romantic relationships: A cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(3), 294–302. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0147176710000118?via%3Dihub

Brinton, D. G. (1886). The Conception of Love in Some American Languages. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 23(124), 546–561. http://www.jstor.org/stable/983335

Gumperz, J. J. (1962). Types of Linguistic Communities. Anthropological Linguistics, 4(1), 28–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30022343

Lindholm, C. (2006). Romantic Love and Anthropology. Etnofoor, 19(1). 5–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25758107

Sergeyevna Kim. (2021). EXPRESSION OF LOVE AS LINGVOCULTURAL AND GENDER LINGUISTIC CONCEPT AND ITS REFLECTION IN DIFFERENT CULTURES. CURRENT RESEARCH JOURNAL OF PHILOLOGICAL SCIENCES, 2(5), 48–54. https://masterjournals.com/index.php/crjps/article/view/89/77