Jacqueline Aguirre, Josiah Apodaca, Kaitlyn Khoe, Mason Uesugi, Wonjun Kim

Code-switching, or the use of more than one language, dialect, or code in an utterance or conversation, can be a way to signal identity. This study compares two sources of code-switching — conversations from media, specifically Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), and conversations in real life — by categorizing utterances and types of code-switching. This study investigates the representation of code-switching in bilingual media and the similarities and differences to code-switching in daily life. The real life conversations were conducted with Mandarin-English bilinguals, and the two conversations ran for 8 and 10 minutes. The findings demonstrated that intersentential switching occurred more often in this particular media, while intrasentential switching was preferred by the real-life speakers. The various types and functions of code-switching were present in the media, which was expected given the larger sample size and production resources and timelines. Nonetheless, both case studies demonstrated significant levels and mannerisms of code-switching, aligning with the proposed variables and categories. Further studies could utilize other syntactic properties, pitch contours, and tonal articulations in order to auditorily represent accuracies and behaviors of code-switches as more bilingual media makes its way into the American entertainment landscape.

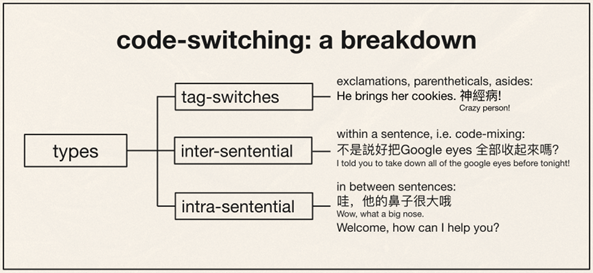

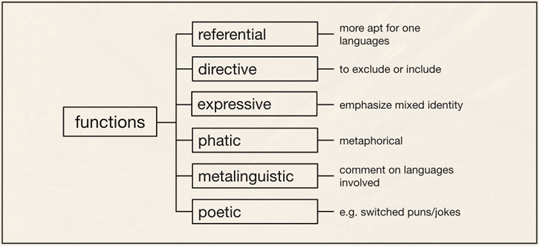

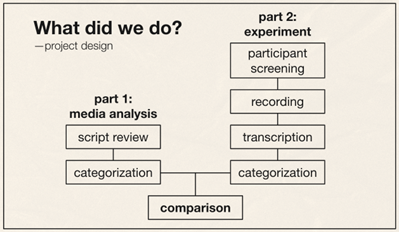

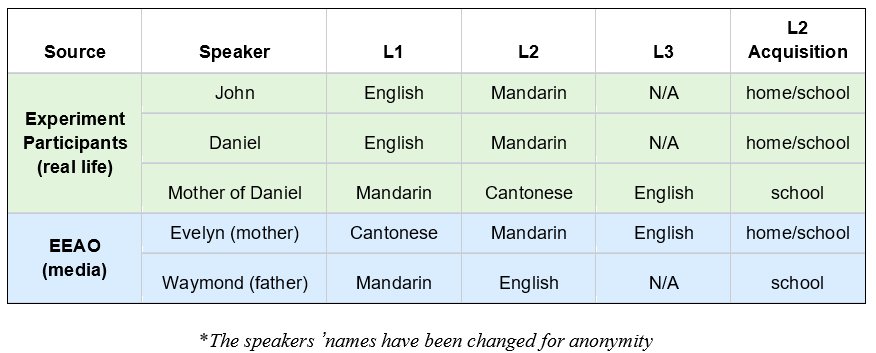

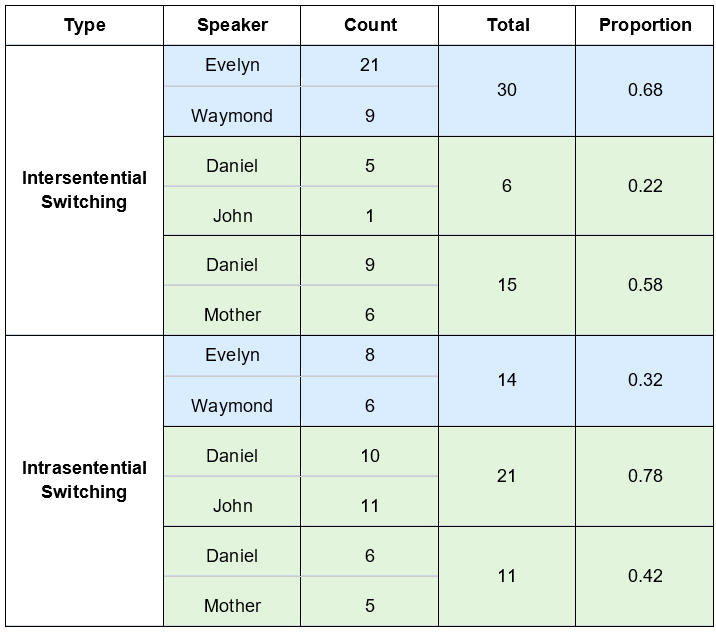

Introduction and Background Code-switching (CS) refers to when a speaker alternates between two or more languages, or language varieties, within a single sentence or interaction. Code-switching is a linguistic function mostly used in bilingual speech communities to convey a mutual “in-group” status between speakers, as the ability to code-switch demonstrates proficiency in both of the utilized languages. Our study seeks to answer these questions: How is code-switching represented in media? What are the differences and similarities to code-switching in everyday life? Deriving from the studies conducted by Shen, Gahl, and Johnson on English-to-Mandarin code-switches, we compared the types of code-switching between Mandarin and English in media, through the 2022 film Everything Everywhere All at Once (EEAO), versus real life to see how accurately code-switching is being represented. The aforementioned study by the researchers suggest the existence of “switch cost,” as the English-Mandarin bilinguals consistently displayed slower reaction times specific to the code-switches in sentence-medial positions, as highlighted in their eye tracking experiment (Shen et al,. 2020). However, while there are many studies giving structure to code-switching, there are fewer applying them to media. Our target population for this project were Mandarin Chinese and English bilingual speakers. Mandarin Chinese belongs to the language family of Sino-Tibetan languages, which is under the Sinitic branch (Odinye 2015). Internationally, about 1.3 billion people use the language, being the official language of China and Taiwan (Odinye 2015). There are three different types of code-switching: tag-switches, which are exclamations, parentheticals or an aside in another language than the rest of the sentence; intrasentential switches, which occur in the middle of the sentence and are typically called code-mixing; and intersentential switches, which occur between sentences (Appel & Muyusken, 2006). We will use these categories in our data analysis to see if some forms of media uphold current code-switching practices. Code-switching in a sentence can also serve different functions depending on the speaker, topic, and context of the language used. Researchers Appel & Muyuskend determined six categories as follows: (1) referential, where some subjects or words are more apt for one language, perhaps due to a lack of knowledge; (2) directive, to exclude or include the hearer; (3) expressive, emphasizing mixed identity; (4) phatic, or metaphorical switching; (5) metalinguistic, to comment indirectly or directly on the languages involved; and (6) poetic, which are switched puns or jokes (Appel & Muyusken, 2006). There is going to be a lot left out about the filmmakers here, but in terms of context about the media that is relevant to code-switching, one of the writer/director duo ‘the Daniels,’ Kwan, is a second-generation Chinese-American. Having been in a Chinese Mandarin and English home environment, he is likely comfortable with engaging in code-switching because of his multilingual parents. One of the producers, Jonathan Wang, hopped on this project also because he wanted to tell a story inspired by his own immigrant parents, so he likely had a hand in ensuring language accuracy, like with the Cantonese, alongside with several translators. With this background in mind, we hypothesized that the movie’s representation of code-switching should be fairly accurate to how speakers code switch in real life. We hypothesize that the participants and the script should have similar examples and amounts of code-switching in type and function within the given environmental parameters, as established earlier. Our research will help determine whether change is needed in how bilingualism is being represented, or if there is already a solid structure in place for new media to follow. Methods Our project design comes in two parts: analyzing the media and analyzing a conversation in real-life. The script had both lines as they were spoken along with translations, so we could categorize them based on type of CS. We applied that same process to two conversations, around 10 minutes each, recorded between two sets of participants. They did know they were being recorded but eventually seemed to forget (over a period of around 10 minutes for each set), so the conversation seemed to flow naturally, with them code-switching subconsciously. We then analyzed the two sources of code-switching and made comparisons. For the screening process, we found our participants based on a language background survey collecting information, such as their L1, L2, and how they acquired their L2, as shown above. The characters’ method of L2 acquisition and L3 is speculated based on context. It is also likely that Evelyn is a simultaneous bilingual in Cantonese and Mandarin. Only the L2 acquisition method is listed, as it is relevant to our focus on bilingual speakers. Two of the participants (John and Daniel) were close cousins to reflect, while not exactly, the close relationship between Raymond and Evelyn. We also had one of them talk to their own mother to see if there would be a change with the different social dynamic. Results and Analysis The table below shows the tallies for the types of code-switching used in the EEAO script (the blue indicating code-switching in media) and the conversations recorded with our participants (green for real-life code-switching). Since the conversations were not exactly the same amount of time, the proportions for each type of CS were calculated by dividing the total for each conversation by the count. There was insignificant information for tag switching in both the script and recordings, so it was left out of the table. Waymond and Evelyn used intersentential switching more than intrasentential (30 versus 14 times). That pattern is the same for Daniel and his mother (15 versus 11 times), while Daniel and John opted for more intrasentential switching (6 versus 21 times). The type of CS (intrasentential) that is more common for Daniel and his mother, whose language background and fluency matches best with EEAO characters, is the same as in EEAO conversations. As for functions, each pair (Daniel and John, and Daniel and his mother) were dominant in the referential function, where some words or phrases are more easily expressed in one language. This outcome is likely because of the speakers’ proficiency in their second language — Mandarin. In a self-reported survey, both Daniel and John rated their L2 proficiency as a 3. The expressive and poetic function appear in the recorded conversations (CS was also used to repeat and clarify). The directive function likely does not appear in these conversations because they were recorded in isolated, controlled environments. Had they been in more natural environments, out in public, it is likely that the directive function would appear. As for the functions present in the EEAO conversation, they were also dominant in the referential function of code-switching, with directive being the second most used. Considering the characters, Waymond and Evelyn, immigrated to America and were likely not exposed to their L2 (English) until later, it makes sense that the referential expression is dominant for them as well. Regarding their use of the directive function, this is most likely due to Waymond and Evelyn being in various environments where there was a third-party to exclude or include (e.g., customers, Gong Gong). Additionally, unlike our speakers, the expressive function does not appear in the movie, but the poetic function does show up once. Based on these results, it seems that the code-switching in EEAO supports the theory of the different types and functions of code-switching. When comparing our speakers’ code-switching with the movie, both align in having referential code-switching be primarily used in communication. Though with our speakers, they showed slightly more variety in function, as they covered expressive functions while the movie did not. While the movie significantly used the directive function, our speakers did not. Again, we conclude that this is due to a difference in environments between the speakers. Discussion and Conclusion The data promotes the idea that EEAO and its representation of code-switching is accurate. Since Daniel’s code-switching varied based on the hearers (with his cousin versus his mother), the movie’s representation is also accurate in representing how code-switching is employed for differing functions based on environment. While the conversations and media we analyzed ended up with similarities, affirming our hypothesis of EEAO being an accurate representation of code-switching, further research is needed to extend these results to media in general. After studying natural conversations of English-Mandarin bilinguals, researcher Xitong Zhang found that “the occurrence of code-switching not only depends on the language ability of the speaker, but also the purpose and the environment in which the conversation occurs” (Zhang, 2019, p. 44). One of the ways to expand this study in the future would be to observe participants in more environments and situations over longer periods of time (e.g., recording conversations over the course of a week) because EEAO has more environments. This choice would provide more data for analysis and allow for a richer case study of CS. It would also help to have participants whose language background better matches the characters even better because Daniel and John did not have the same L1/L2 as Waymond and Evelyn. However, the time constraint of this study provided a limited participant pool to see how identity and linguistic competency affect code-switching. We could also look into instances of “bad” code-switching in media, likely tied to older media sources, to develop concrete standards of accurate code-switching — including what not to do — for future representations of the bilingual experience. We could just look at more films, maybe in other language pairings, or other sources of media, like TV shows, whether good or bad examples, as well. In his video essay “English. Language. Movies. Parasite,” Kyle Kallgren studies code-switching in the 2019 film Parasite and the cultural implications of mixing English and Korean in conversation. The Parks, a rich family, often uses English to confide in each other or to establish solidarity with their hired workers. It seems that English is worked into the plot accents, signifying the divide between the poor and rich families. In a similar fashion, language boundaries reinforce relationships in the plot of EEAO, with code-switching being a big part of it. America tends to fawn over foreign culture without realizing it is their own culture being sold back to them — just accented — which is probably why they find connection to it. There is something to be said about how these two movies employ code-switching as a tool to hint at language hierarchies. Studying the use of language and code-switching in media like this is important for providing a foundation for how to approach appropriate representation in media. There are harmful social implications if one does not consider the influence of how language is used in movies. As language hierarchies exist in reality, noticing and replicating them in media will only reinforce them when they should be dismantled. Understanding how media perpetuates practices in which social classes are tied to certain manners of speaking can help us counteract that. References Anindita, K. (2022). An Analysis of Code-Switching in the Movie “Luca”. ELTR Journal, 7(1 23-33. https://doi.org/10.37147/eltr.v7i1.164 Appel, R. & Muysken, P. (2006). Language Contact and Bilingualism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Chen, Z., & Liu, X. (2023). Types and Functions of Code-Switching in the Film Everything Everywhere All at Once. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, 13, 171-176. https://doi.org/10.54097/ehss.v13i.7889. Kwan, D. and Scheinert, D. (Writer). (2022). Everything Everywhere All at Once. A24. Odinye, S. I. (2015). Phonology of Mandarin Chinese: Pinyin Vs. IPA. Quarterly Journal of Chinese Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 51–58. Reformadita, A., & Setyaji, A. (2021, October). Code-Switching Analysis on Pixar’s “Coco” Movie. In Undergraduate Conference on Applied Linguistics, Linguistics, and Literature. (Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 26-37). Shen, A., Gahl, S., & Johnson, K. (2020). Didn’t hear that coming: Effects of withholding phonetic cues to code-switching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 23(5), 1020-1031. Zhang, X. (2019). Code-Switching in English-Chinese Ordinary Conversations. TESOL Working Paper Series, 17, 38-45. Appendix A