Jasmine Beroukhim, Nicole Palleja, Marydith Macabale, and Jaee Shin

Netflix’s hit dating show, Love is Blind has captured the attention of millions of viewers for its original take and format. In the show the contestants are separated by gender, and converse with one another through pods where a wall separates them from seeing each other. The show reimagines dating by erasing material aspects of a contestant’s identity right down to the sound of their voice. Throughout the show noticeable shifts in voice were apparent, and while it is well documented that humans have an innate capacity to shift styles through their voices, little research has been completed on how vocal changes are expressed in the discourse of reality dating shows. Our study focused on the implications of vocal modulations in the context of reality television to investigate how an individual’s voice can contribute to the shaping of identity. In discussing this topic, we are interested in how the human voice can be used to influence perception and how women’s voices may reflect their perceived gender roles. We believe it is crucial to better understand the power of the human voice in leveraging perceptions and the societal and cultural reasons why a woman’s voice may change when speaking to a potential partner.

Introduction and Background

Our research focused on the first episode from Love is Blind which featured Jessica Batton, a 34-year-old white woman from Chicago, who works as a Regional Manager. The public coined her iconic voice as a “sexy baby voice,” but the “sexy baby voice” was only apparent when she spoke to potential matches and disappeared when she relayed her experience in camera confessional interviews. “Sexy baby voice” according to linguists is achieved by raising your pitch and engaging in upspeak where the phrase ends with a rising pitch. Through our analysis we labeled Jessica’s two voices as “sexy baby voice” and her “professional voice.” In order to concretely measure the changes of her vocal modulation our study utilized the linguistic tool, PRAAT by inputting voice recordings from the show and comparing Jessica’s “sexy baby voice” used in the pods versus her “professional voice” utilized in the individual camera confessionals. Furthermore, we used conversational analysis to juxtapose her dual voices and to deepen our understanding of Jessica and determine if her pitch use fluctuated in accordance to the subject of her discussion. By creating a transcript between Jessica and her potential partner, we were able to illustrate the nuanced changes described through PRAAT and what the speaker was indexing through her vocal modulation.

Hypothesis

We expect Jessica to employ a higher vocal pitch when she is interacting with a male suitor, in the pods versus utilizing lower vocal pitch, consistent with a professional speaking voice, during her individual, camera confessionals. We expected our research findings to be consistent with our hypothesis in accordance with Jessica’s fluctuating voice pitch depending on her contextual setting and how such use of varying vocal pitches are reflective of her attempt to index two different identities in her personal and professional life.

Methodology/Project Design

We chose to limit our primary data collection to Season 1, Episode 1, entitled Is Love Blind as Jessica garnered the most screen time compared to other episodes later in the season, as she navigated the complexities of finding true love between two potential partners: Barnett and Mark. This case study was particularly notable to use because her modulating voice samples, according to professional or personal context, would provide us with substantial material to analyze throughout the episode. In our research, we collected a total of four samples and chose samples where a dramatic change in voice was evident Another reason for choosing these four samples was their back-to-back nature. Jessica used her professional voice when giving an interview and then used her “sexy baby voice” moments later when entering the pod. We then put the four samples into PRATT, which allowed us to draw conclusions about formant values, pitch, and intensity, when speaking to future relationship prospects versus one-on-one camera confessional. We then created a transcript of each of the 4 samples and used conversational analysis methodologies. We then collected 12 additional samples that we ran through PRATT with the purpose of observing her pitch formants. The subject content of the vocal samples was not analyzed. We watched the relevant episode, recorded Jessica’s speech, transcribed her voice samples into PRATT, created a transcript, and subsequently analyzed her pitch patterns in relation to what she was saying. By carefully analyzing the linguistic features of Jessica’s voice, we were able to deepen our understanding of Jessica as a social being as she indexed construction of her identity when speaking to relationship prospects versus addressing the camera directly in individual confessionals.

Literature Review: Woman’s Vocal modulation in Dating Context

Helen Sautason, an English and Linguistic Professor at York St. John University in London offers insight into why a woman’s voice may change when speaking to a potential partner. In Sautason’s words, “the speaker will put themselves in a position where they sound less powerful because they have a belief that men find that attractive, and they don’t want (men) to feel threatened. There’s always been a value placed on girlish femininity” (Dazed, 2020, p. 2). Additionally, in a study entitled, “Voice Pitch Modulation in Human Mate Choice,” thirty adult men and women were observed in real time speed-dating events; their vocal patterns were analyzed for pitch changes. What was concluded from this study was that “women spoke in a higher-pitched and less monotone voice on speed dates with men they chose as potential mates.” The authors of the research observed that “the trade-off implied by this dichotomy suggests that women may volitionally raise their voice pitch to signal youth and femininity but lower their pitch in contexts where they wish to be taken seriously, or to indicate intimacy to a listener” (Pisanski et al., 2018, p. 2). As we examine our focus episode, we see that this observation is evident.

Data Analysis: Pitch Formants

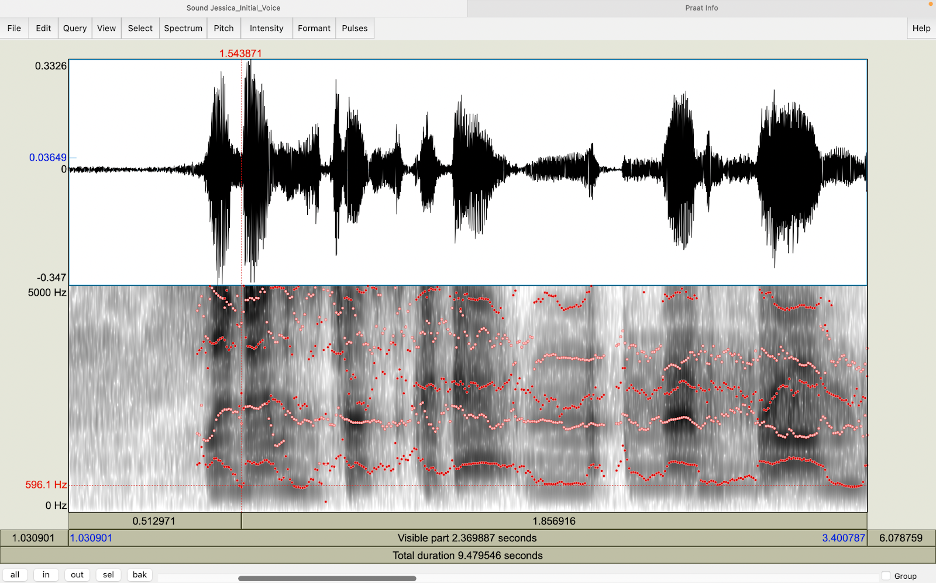

The differences in frequencies translate directly to pitch differentiation. A lower frequency indicates a lower pitch, while a higher frequency indicates a higher pitch. Figure 1 is a visual representation of Jessica’s first on-screen confessional where she introduces herself as a contestant on the show for the first time. Here she used her professional voice which produced a low F1 frequency of 606Hz.

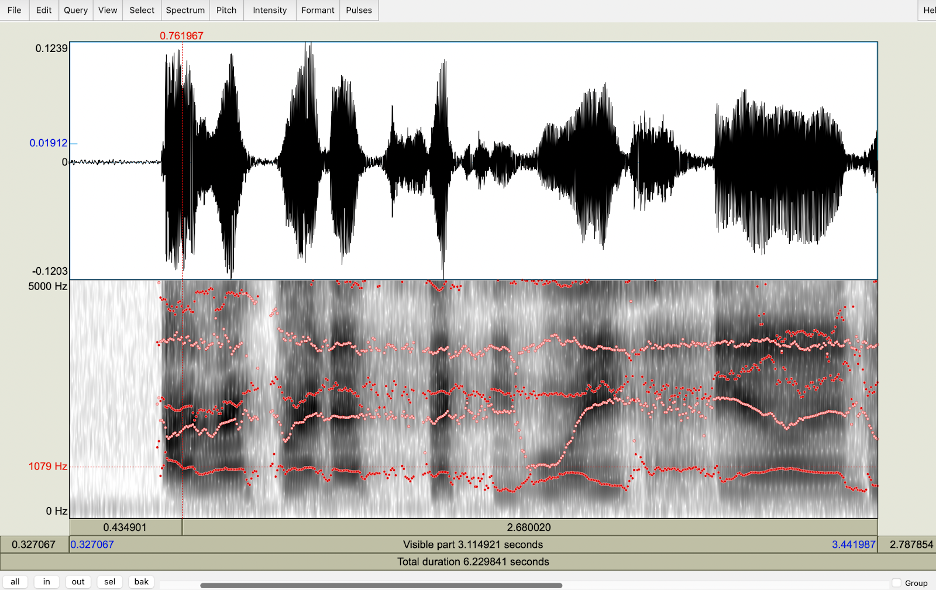

Figure 2 is a visual representation of Jessica’s first time in the pods where she meets Barnett. Here she used her sexy which produced a high F1 frequency of 1069Hz.

Her use of two different voices and varying pitches is a direct attempt to index two different identities. There is a juxtaposition of two “first moments” that are happening within the context of Jessica’s introduction as an on-screen character to the world. Excerpt 1 provides a direct transcription of what Jessica says in her camera confessional, where her F1 produced a frequency of 606Hz (line 1).

Excerpt 1: Jessica’s First Confessional Interview “Professional Voice” [6:38- 7:00] 1 Jess: My name is Jessica Batton I'm from Rock Falls Illinois 2 <I’ve had> a rigid set of: standards I would only date a 3 guy between 1 to 5 years older I would only date (0.1) 4 athletes because I’m really athletic

Here, the audience is led to believe that Jessica is an established and serious woman looking for a mature relationship, to fit the bill of her desired qualities of a man, which is consistent with her use of a lower pitch voice register. The second introduction of Jessica portrays a different picture of her identity to Barnett, which contrasts sharply with her introduction to the world; a direct transcription of what Jessica says in the pods can be found in Excerpt 2 where her F1 produced a frequency of 1069Hz (line 8).

Excerpt 2: Jessica’s Initial Pod Meeting “Sexy Baby Voice” [6:38- 7:00] 1 Jess: But I’m 34 years old and I may not find someone based 2 on:: the criteria that I’ve::: put in place for myself 3 I’m ready to start a family and:: I want to have::: 4 the most perfect marriage 5 Mark: What’s your name, 6 Jess: I’m Jessica_ 7 Mark: Jessica_ Nice to meet you Jessica I’m Mark 8 Jess: Nice to meet you Mark ?

Suddenly, she is bubbly, girlish, and demure, consistent with her use of the high pitch, feminine, sexy-baby voice register. It is implied that Jessica’s use of the sexy baby voice serves her the purpose of portraying herself as a likable woman that should be seen as desirable to the male gaze, or in this case, the male ear. Shortly after Jessica’s sexy baby voice driven interaction with Barnett, it appears that her high-pitched voice had captivated the attention of Barnett who comments on how nice her voice sounds.

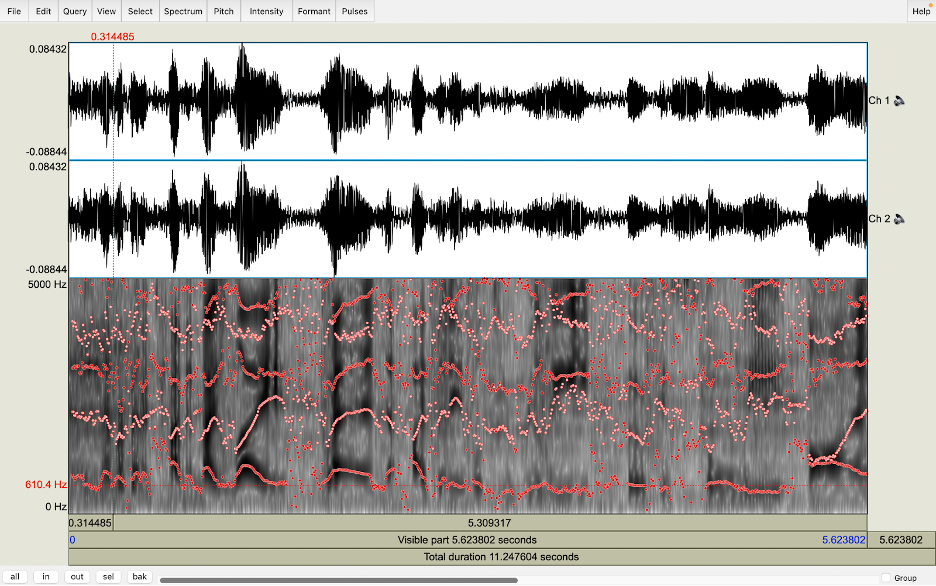

Similarly, the initial meeting between Jessica and Mark, her second potential romantic partner on the show, merited our attention and examination as it was another unique instance of Jessica’s voice modulation. Before meeting Mark Jessica gave a camera confessional discussing her past dating. When analyzing the F1 formant frequencies of her “professional voice,” in her camera confessional her F1 frequency produced a value of: 607Hz. The visual representation of her formants can be found in Figure 3.

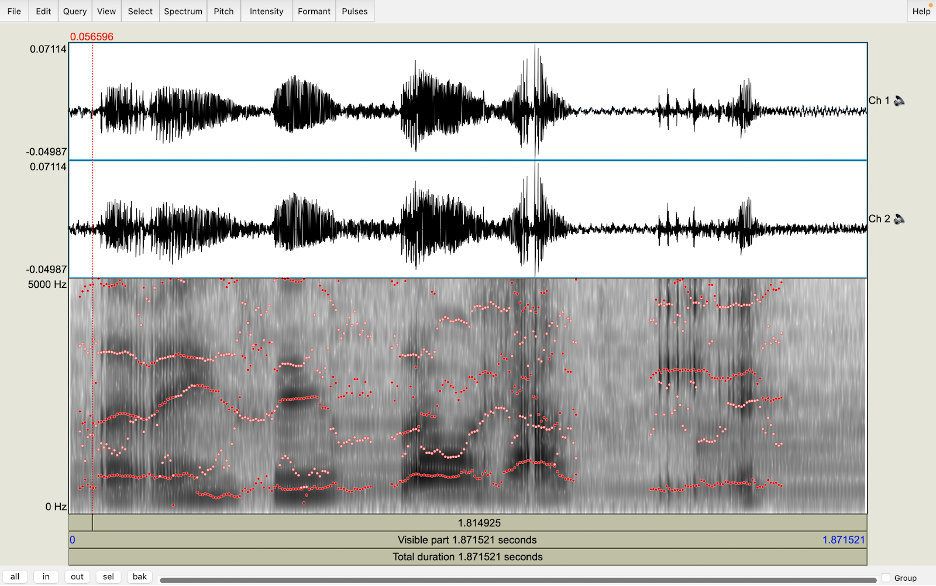

Minutes after Jessica’s camera confessional Jessica enters the pods where Jessica leverages her “sexy-baby” voice. In the pods, her pitch had increased and produced a value of 810Hz, a drastic difference in pitch from her interview frequency of 607Hz. The visual representation of her formants can be seen in Figure 4.

Excerpt 3 provides a transcription of Jessica’s use of her professional voice, which produced a low F1 of 607Hz (lines 1-4).

Excerpt 3: Jessica’s Confessional Interview “Professional Voice” [30:23-30:30] 1 Jess: There’s never been a time in my life (.) when I’ve been 2 able to really (0.1) focus solely on finding love_ 3 here in the experiment (0.1) you spend every second 4 of every minute searching for your soul mate

Jessica’s statement pushes the perception of Jessica’s social identity as a professional “working woman”’ who does not have time to spare to be dating. In the study, “Voice Pitch Modulation In Human Mate Choice”, the authors explain the common perception of women who have a lower-pitched voice as “consistently judged as more dominant, competent and mature, and as better leaders than women with a higher voice pitch” (Pisanski et al., 2018, p. 2). It is therefore not a coincidence that Jessica uses her “professional voice” emulating a pitch drop when speaking about her personal life and lack of time to engage in dating.

Excerpt 4 provides a direct transcription of Jessica’s conversations with Mark, where her sexy baby voice was used frequently, and produced a high F1 frequency of 810Hz.

Excerpt 4: Jessica’s Pod Meeting “Sexy Baby Voice” [31:26- 32:11] 1 Mark: holy shit we’re the same fucking person (.) and it's 2 like (.) I want to raise my kids with religion 3 Christianity you know because that’s how I was raised 4 Jess: yeah 5 Mark: and you know (.) I have a tattoo on my ribs (.) like 6 it’s a cross with my parents initials on the top and 7 bottom (.) my sister and brother on an empty plaque 8 Jess: wow 9 Mark: so when I have kids I can initial their names on it 10 (.) and Psalm 19:14 going across it 11 Jess: °I love that (.) that makes me so happy 12 Mark: (( laughs)) 13 (0.2) 14 Mark: how many kids do you want? 15 Jess: three 16 Mark: three (,) ? I'm down 17 Jess: ok 18 Mark: I want two boys and a girl 19 Jess: I like that , 20 Mark: my face hurts 21 Jess: why ? 22 Mark: I’m smiling a lot 23 Jess: you are? 24 Mark: maybe 25 Jess: that makes me so happy

Throughout the conversation, her replies were short and affirmative of Mark’s feelings and sentiments about religion and the number of children they desire. A study titled “New Zealand Women Are Good to Talk to: An Analysis of Politeness Strategies In Interaction” explains that American women are supportive and cooperative conversationalists; they act as an ideal and responsive audience – usually to men.” (Holmes, 1993, p. 92) The idea that women often act as “an ideal and responsive audience” to men, might explain the use of Jessica’s “sexy baby voice” in this interaction with Mark and the need to protect his ego. There exists a contrast between Jessica’s dual identities because with her professional voice, we interpret her as a head strong working woman, versus with her sexy baby voice we tend to perceive her as flirty, and submissive “dumb blonde” archetype (refer to Figure 5 for an image of Jessica).

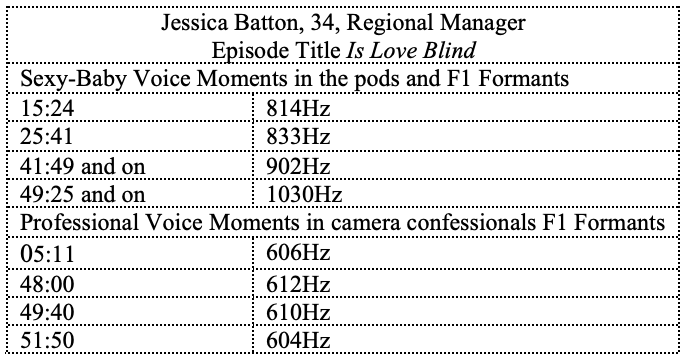

For the purposes of confirming our hypothesis, we collected further data reinforcing Jessica’s consistent use of vocal modulations in response to alternating scenarios. The data presented in Figure 6 is a series of F1 frequencies that reaffirm Jessica’s use of higher pitch in her romantic interactions and lower pitch in her on-screen camera confessionals while reflecting on her life experiences.

Conclusions

There have been numerous studies conducted on voice modulation in various settings and even dating simulations, however, the objective of our study is to fill the gap in the body of research in the context of reality dating television, analyzing how individuals use their voices as a means of connecting with a potential partner who cannot physically see them.

In Love is Blind, we found that Jessica Batton deliberately altered her voice in order to make her sound more attractive to potential suitors, and that her sexy baby voice contrasted sharply with the pitch frequency she used when speaking directly to the camera. Therefore, based on Jessica’s varying voice modulation patterns in response to differentiated social contexts, we reaffirm the notion that voice can be used as a tool to construct and index an identity in specific social environments. When completing our case study, we were cognizant of the limitations, more so, that a reality television show can easily manipulate an image of a woman through the editing of the production team Our research was also limited as we only conducted a case study and did not analyze if this applied to others on the show, and did not analyze other episodes to mark if there was a change. In light of this, although our study does not definitively establish that women change their voice in the situational context of all reality dating television, it is one glaring instance of the degree to which shifting vocal modulation can affect the external perception of a person’s identity.

References

Dazed. (2020, March 9). Investigating the ‘sexy baby voice’ phenomenon. Dazed.

https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/48255/1/investigating-the-sexy-baby-voice-phenomenon-love-isblind#:~:text=The%20’sexy%20baby%20voice’%20typically,s

mall%20body%20size%20(sigh).

Guardian News and Media. (2020, February 26). What is ‘sexy baby voice’? We spoke to a sociologist to find out more. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/feb/26/what-is-sexy-baby-voicesociolo gist

Holmes, J. (2002, July 3). New Zealand women are good to talk to: An analysis of politeness strategies in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378216693900784

Hughes, S. M., & Puts, D. A. (2021, November 1). Vocal modulation in human mating and competition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rstb.2020.0388

Pisanski, K., Plachetka , J., Gmiterek , M., & Reby, D. (2018, December 18). Voice pitch modulation in human mate choice. Proceedings. Biological sciences. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30963886/#:~:text=Within%2Dindividual%20analyses%20indicated%20that,a%20mutual%20preference%20(matches)

Zurbriggen, E. L., & Morgan, E. M. (2006, January). Who wants to marry a millionaire? reality dating television programs, attitudes toward sex, and sexual behaviors – sex roles. SpringerLink. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11199-005-8865-2