Roni Grushkevich, Claire Lim, Kendall Vanderwouw, Daniel Zhou

Who is the most memorable villain you remember from your childhood era? We hypothesize that most individuals will remember a villain portrayed with a heavy accent. This is due to the phenomenon of othering and the idea that children will have a hard time connecting with a character that sounds different from them and the standard variety. We will use the childhood show, Phineas and Ferb, to see if this is true. Through the conduction of a survey, analyzing voice recordings in Praat, and doing sound analysis from an episode of Phineas and Ferb we will be able to see the phenomenon of othering. In Praat, we proved this phenomenon by showing that Dr. Doofenshmirtz, the antagonist, has a lower /æ/ F1 formant than Phineas and a native American English speaker. Additionally, analyzing the Hail Doofania episode, we were able to prove that Doofenshmirtz pronounced 6 sounds differently from a native American English speaker. All this proves the idea that villains are portrayed differently with negative attributes on children’s TV shows.

Introduction/Background

Our group proposes to do research on the effects of villainization in children’s shows, which has possible long-term implications on people’s perceptions of membership in their ingroup. This membership perception can be encapsulated by the phenomenon of othering. Othering is a process in which a more powerful and/or influential group reinforces differences and authority over another (Williams & Korn, 2017). Hence, our project aims to look at whether adoption of othering by children’s shows’ producers for villainous characters influences the audience’s perceptions of who is “good” (ingroup) and who is “bad” (outgroup).

Previous studies conducted by sociolinguists Calvin Gidney and Julie Dobrow (1998) indicated most foreign accented villains in children’s shows were exclusively European such as German, British, and Russian. These accents in particular are often characterized with high arrogance, intelligence, and socioeconomic status while low on friendliness, pleasantness, and honesty (Shah, 2019). These sentiments towards European accents may be reflective of World War II, Revolutionary War, and Cold War hostilities that dominated media/propaganda during the time.

We choose to look at the children’s show Phineas and Ferb, where the main antagonist, Dr. Doofenshmirtz, is portrayed with an exaggerated foreign accent. Heroes typically speak in the standard dialect and embody idealistic standards (Dobrow & Gidney, 1998), which holds true for the show’s protagonists, Phineas and Ferb. Through these differences in speech patterns, nonstandard accents become associated with “otherness” and antagonism (Constable, 2021).

Specifically, we will examine the phonetic production of vowels by accented English-speaking villains. When villains “mispronounce” English vowels, it is an obvious symbol of their communicative differences. That said, Dr. Doofenshmirtz is a great character to analyze as he does not speak the standard variety like most viewers. In addition, we plan to explore another linguistic variable that distinguishes Doofenshmirtz’s speech from the American standard.

Survey

To supplement the studies we will be citing, we also found it important to explore the existence of accented villains within the media we consumed as children and the types of accents they adopt. To do this, we constructed a preliminary survey prompting college-aged students (aged 18 to 24) to name “the most memorable villain from the movies/shows [they] watched as a child (age 2-10).” In the second iteration of the survey, participants were asked if they distinctly recall the villain expressing an accent coupled with any overall impressions they had of the villain. The survey was shared amongst UCLA students and other college friends, as long as all participants fell within the age range.

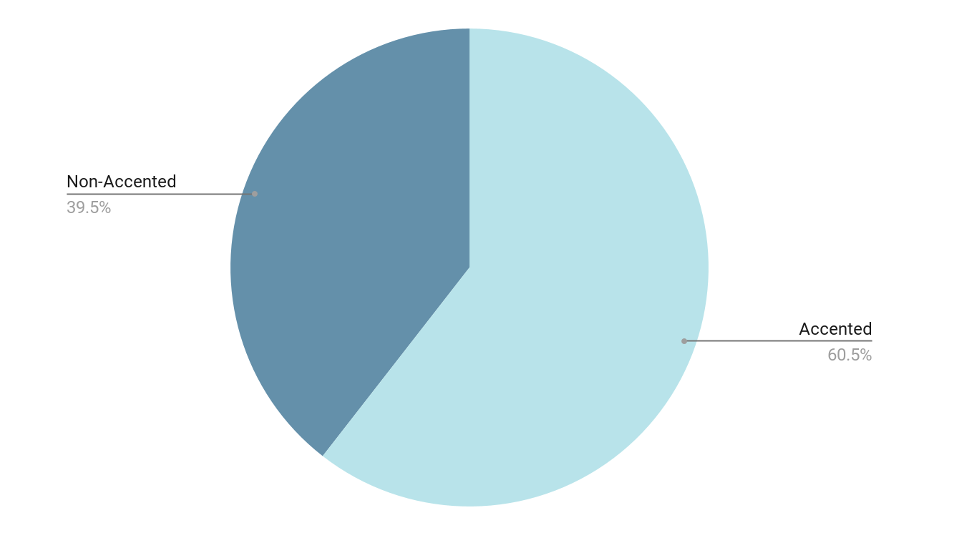

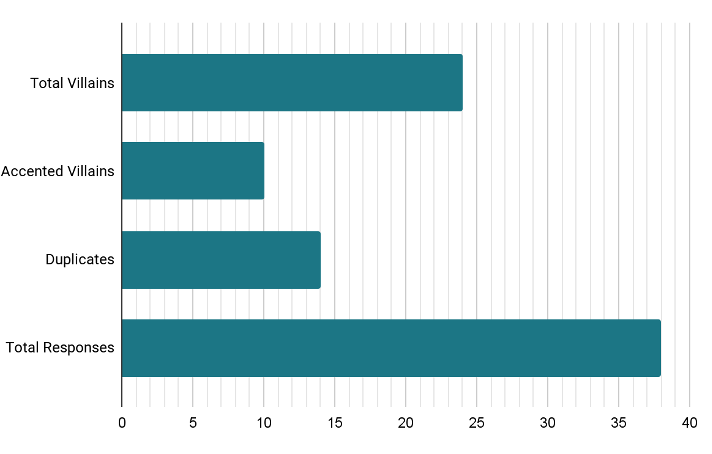

The results of the survey demonstrated a strong prevalence of foreign accents in the villains chosen, evidenced by Figure 1. Out of 38 total responses, 23 responses were accented villains. Not only was a clear statistical significance demonstrated of the trend, but actually a majority of the villain choices were associated with foreign accents. Given the breadth of types of respondents coming from California to Uganda to Singapore accompanied by the complete autonomy of selection of the villain, the survey results highlight the abundance of accented villains in popular media.

In addition, the values from Figure 2 present an interesting observation regarding the variety and uniqueness of villain selections. In total there were only 24 unique villains chosen. Of those 24 villains, only 10 were actually accented. The disparity between the number of accented villains and number of accented responses is explained by the incredibly high number of repeat selections of villains that are accented. For instance, Ursula (who adopts a condescending British accent) from The Little Mermaid was listed five times and Dr. Doofenshmirtz was repeated four times. In fact, of the 14 duplicate responses, 12 contained accented villains. This informs on the consolidation of popular children’s media; most children consume much of the same television shows and movies (Disney).

Another interesting note revolves around the traits that stand out or make the villain memorable. The comments on the impressions of the villain fell into two camps: “scary”/“intimidating” or “cool”/“respectable”. Not a single comment mentioned how the villain sounds or their voice. The “othering” of the villains through accented speech takes an implicit or passive effect on the viewer rather than being the focal point. The viewer then subconsciously categorizes the character in the out group. These observations and key takeaways from the survey helped propel the main research portion of the study and guided the choice of Dr. Heinz Doofenshmirtz as the character to analyze.

Methods

Our main goal in collecting data was to show that Doofenshmirtz follows German pronunciation patterns when speaking English. His nonstandard speech is meant to “other” him from the protagonists, determining his characterization as “bad.” Therefore, our data took a two-pronged approach: first, we used the spectrogram software Praat to analyze sound files of subjects speaking. This way, we could look at Doofenshmirtz’s articulatory properties and point to which features distinguish him as German-sounding. Then, we sent speakers of English to watch an episode of the show and comment on which non-standard features they heard him using. Between these two methods, we gained an understanding of both how Doofenshmirtz speaks and how English-speakers perceive his speech.

When researching in Praat, we looked at the vowels /i/ and /æ/. /i/ exists in both English and German, so we expected no statistical difference in the articulation of a German versus English speaker. On the other hand, the /æ/ sound exists in English but not German. In English, German-speakers tend to replace this sound with the higher vowel /ɛ/, which is easier to produce based on its presence in the German language.

We used samples from four subjects in Praat, two German-accented speakers and two “standard” American speakers. Our “baseline” German accent came from a 50-year-old native speaker who grew up in Düsseldorf but now lives in California. We were particularly interested to see how his speech compared to the German-accented Doofenshmirtz (who, intriguingly enough, was voiced by an American actor). We also took a sample from an 18-year-old native Californian, who we determined to have “standard” vowel production. Finally, we compared her speech to the pronunciation of the show’s protagonist, Phinneas (who was also voiced by an American actor, but was intended to have “standard” production). We wanted to ensure that our samples were comparable, so our first three subjects all produced Doofenshmirtz’s catchphrase: “Curse you, Perry the Platypus!” (/i/ is found in the word /ˈperi /, while /æ/ is prominent in /ˈplætəpəs/). Although no samples existed of Phinneas saying this sentence, we located a similar sentence where he still said both words in proximity.

Our other group of data came from observing Doofenshmirtz’s speech throughout an episode. Inherently, the sounds of the German language differ from those of English. Some sounds feel tricky or unnatural to non-native speakers. Speakers often replace an English sound with a similar foreign counterpart they know how to produce, just as how a German speaker might replace /æ/ with the /ɛ/ sound of their native language. Often, it is this sound substitution that creates the phenomenon of an accent. For our project, we wanted to see how American individuals perceived Doofenshmirtz’s so-called accent. We asked two college-aged subjects to watch Season 1, Episode 26 – “Out of Toon / Hail Doofania” and explain how his speech compares to the substitutions we’d expect of a German-speaker.

Results/Analysis

Praat

In Praat, we used the “View & Edit” feature to analyze something called formants (lines on a spectrogram that indicate a concentration of energy). For this project, we were mainly concerned with the first formant (F1), which shows vowel height. We found that all of our subjects had similar F1 formants for the vowel /i/. Since this sound exists in both languages, non-native speakers made no substitutions when speaking English. Our Hz values ranged from 376.7 to 460, meaning there was less than a 100-Hz difference between how the two most differently accented speakers produced the vowel. Therefore, the data showed no trends in production variations for Germans and Americans in /i/.

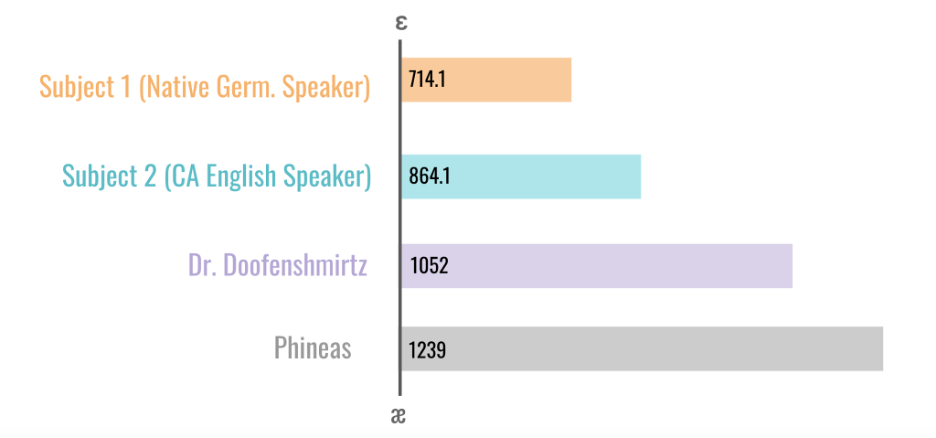

On the other hand, the data showed interesting patterns when it came to /æ/. We predicted that German speakers would have a lower F1 value than English-speakers (due to the fact that /ɛ/ has a lower F1 than /æ/). Overall, we found this to be true. Our authentic German subject had the lowest F1 of the group at 714.1. Likewise, our highest formant value came from “standard” speaker Phineas at 1239. Interestingly, the dubbed voices had a much higher average F1 formant, which we hypothesized had something to do with the nature of the audio files. If we separate our samples by this type of audio file (real speakers vs dubbed speakers), we find that German speakers’ formants are 100-150 Hz lower than those of American speakers. This indicates that they do, in fact, produce ash more similar to /ɛ/.

Sound Analysis

We paid attention to foreign-sounding allophones, compared to a Californian English speaker’s pronunciation, in Hail Doofania. We only analyzed Dr. Doofenshmirtz’s speech and ignored any pronunciation deviations in his song.

In his speech, we identified 6 sounds that were pronounced differently from how a Californian English speaker would pronounce the sounds. The most frequently occurring deviations were his pronunciation of the alveolar approximant ([ɹ]) and voiced postalveolar affricate ([dʒ]). 23 of the 34 deviations were [ɹ] and 6 deviations were [dʒ]. We identified pronunciation deviations just from hearing and our personal judgments given the time and resource constraints of this project.

We looked at the German International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) sounds to see if the allophones used by Dr. Doofenshmirtz were from the German sound repository. We proposed that his mispronunciation of English allophones was because he was borrowing German sounds to pronounce English sounds. But, the sounds that Dr. Doofenshmirtz used were actually not found in the German IPA

As the allophones used by German speakers for the different analyzed sounds were not what Dr. Doofenshmirtz used, we came up with 2 possible explanations to account for Dr. Doofenshmirtz’s different pronunciations.

First, we suggest that the producers might have wanted to distance Dr. Doofenshmirtz from a German identity. Perhaps they wanted Dr. Doofenshmirtz to have some accent aspects which alluded to a German identity but not have the character be too strongly associated with a German identity. Podesva (2011) posits that the creation of an identity or a “persona” utilizes several linguistic features, and different components of a linguistic feature are adopted depending on the context the speaker is in. This suggests that a bricolage of linguistic features are used to construct an identity. For Dr. Doofenshmirtz, this means that his identity as an individual from Drusselstein (a fictional East European country) was not solely reliant on his accent but on other features too. Hence, it is possible that the show’s producers did not use the German allophones to pronounce the different Californian English sounds to index Dr. Doofenshmirtz’s heritage, but utilized other linguistic and non-linguistic features to do so.

Second, it could be because Dr. Doofenshmirtz is voiced by Dan Povenmire, a native Californian English speaker. Thus, Dr. Doofenshmirtz’s mispronunciation could stem from how a Californian English speaker perceives a German accent to sound like and not how an actual German accent sounds like.

Interestingly, we found that our German speaker pronounced the sounds we studied, in the same way that Californian English speakers do. We attribute this to his exposure to the Californian English accent and was able to distinguish the different allophones and use them according to the context he was in.

Discussion and Conclusions

We looked at the amount of time Dr. Doofenshmirtz spoke in Hail Doofania to gauge the significance of his accent’s contribution to his identity. Dr. Doofenshmirtz had 112 seconds of speech time in the 9 minute and 11 second episode (551 seconds). This equates to about 20% of the episode. As such, Doofenshmirtz has only 20% of the episode to leave an impression on the audience, making it crucial for the producers to adopt several indices to create Doofenshmirtz’s character as an “evil scientist”. The identified indices were: his accent, his clothing (lab coat), the content of his speech (his plans to take over the Tri-state Area) and actions (fighting with Perry the Platypus).

We felt that some younger audience members might be too young to comprehend the sinister nature of Dr. Doofenshmirtz’s plans and might instead rely on auditory and visual cues (his accent and attire & fight scenes, respectively) to index Dr. Doofenshmirtz as a villain. By extension, we think that it is possible for these auditory and visual cues to lay the groundwork for associations that these child audiences make with someone who is “bad” and in an outgroup.

Given that it is more likely for children to come across speakers of different accents than people dressed in lab coats in their everyday lives, we believe that it is possible for them to consequently (because of cartoon villains having accents) associate people with accents as members of an outgroup. This demonstrates how accented villains are part of the phenomenon of othering and can influence children’s perception of “good” and “bad”.

We believe that the results we obtained through Praat were very useful. They supported our findings and proved that accented speakers sound different from the standard. We wish we had more time to obtain and analyze more data. On the other hand, the survey results were not very helpful. We were not able to come to any conclusions through the survey results, but we definitely feel that the survey pushed us in the right direction.

One of the most important takeaways that we believe show producers should know is that they must be mindful of the stereotypes they create or reinforce in their audience. These shows have long term implications that heavily influence individuals.

References

Constable, E. (2021, March 17). Dear Disney, stop teaching kids that foreign accents are evil. LHS Epic. https://lhsepic.com/9602/opinion/dear-disney-stop-teaching-kids-that-foreign-accents-are-evil/

Dobrow, J. R., & Gidney, C. L. (1998). The Good, the Bad, and the Foreign: The Use of Dialect in Children’s Animated Television. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 557, 105-119. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1049446

Flege, J. E., Bohn, O.-S., & Jang, S. (1997). Effects of experience on non-native speakers’ production and perception of English vowels. Journal of Phonetics, 24(4), 437-470. ScienceDirect. https://doi.org/10.1006/jpho.1997.0052

Paquette-Smith, M., Buckler, H., White, K. S., Choi, J., & Johnson, E. K. (2019). The Effect of Accent Exposure on Children’s Sociolinguistic Evaluation of Peers. Developmental Psychology, 5(4), 809-822. American Psychological Association. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/dev0000659

Phineas and Ferb Wiki. (n.d.). Drusselstein | Phineas and Ferb Wiki | Fandom. Phineas and Ferb Wiki. https://phineasandferb.fandom.com/wiki/Drusselstein

Shah, A. P. (2019). Why are Certain Accents Judged the Way they are? Decoding Qualitative Patterns of Accent Bias. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 10(3), 128-139. Australian International Academic Centre PTY.LTD. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.10n.3p.128

Sharma, M. (2016). CHAPTER SEVEN: Disney and the Ethnic Other: A Semiotic Analysis of American Identity. In Teaching with Disney (pp. 95-107). Peter Lang AG. Williams, M. G., & Korn, J. (2017). Othering and Fear: Cultural Values and Hiro’s Race in Thomas & Friends’ Hero of the Rails. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 41(1), 22-41. SAGE. 10.1177/0196859916656836