Bingbing Liu, Kejia Zhang, Nina Cai, Ze Ning, Zehao Yao

Recent sociolinguistic studies show interests in exploring people’s language practices and their corresponding social influences. In China, the rapid development of the society has attracted more and more people immigrating from the countryside to the city. Beijing, one of the most prosperous cities in China, welcomes immigrants coming from various cities. When different groups live together, their linguistic varieties actively interact with each other in a long run. This study focuses on the comparison between the insiders who were born and raised in Beijing and latecomers who settled down there in later times. Through observing their usages of [ɹ] sound, this study displays the pattern that latecomers might imitate the pronunciation of this sound and use it daily life, but they will not overcompensate it nor use in inappropriate contexts. Also, this study demonstrates that the acquisition of specific linguistic features is social-cultural affected, which is related to the speaker’s personalities, life experience, and preferences.

Introduction

China has witnessed a dramatic economic boost since the 1970s when the Reform and Opening-up Policy was promoted. Along with the acceleration of industrialization and urbanization, the social classes were changing due to massive internal immigration. Beijing, the most rigorous city in China, was the place where the capital, information, people, and culture were centralized. Numerous people swarmed into the city and settled there. These latecomers not only got used to the life there but also were influenced by local cultures. The use of the accent, the most frequently encounter in daily life, strongly influenced people’s perception of others and their own identities.

One of the most apparent features of the Beijing accent is the rhotacization of the [ɹ] sound, which usually occurs in syllable finals and is used as a diminutive suffix (Eckert 2018). It is often used to distinguish a local from an immigrant because it is hard to imitate and master. This study shows the latecomer’s acquisition and use of the [ɹ] sound in their daily life, and their understanding of the relation between the feature and identity construction. This paper includes several parts. A brief introduction and studies and research at home and abroad will be first presented. Then, the participants’ backgrounds and research methodology are introduced. After that, the data collection and interview recordings are displayed and analyzed. Finally, major findings are discussed in detail.

Literature Review

The rhotacization of [ɹ] sound was firstly studied phonetically because it works as a maker to distinguish a local in Beijing from a non-local. Many scholars have studied this phenomenon. According to Xu (2020), the morphosyntactic meanings of the [ɹ] sound is gradually diminishing, while it is used as a phonetic suffix attached at the end of words. Rather than focusing on the linguistic essence of the [ɹ] sound, other scholars pay attention to the socio-cultural influences of the Beijing accent. Zhang and Liu (2017) conducted a project on Northeast immigrants’ attitudes towards the Beijing accent. In their project, they found that female immigrants who tend to imitate [ɹ] sound are perceived as more educated, professional, and powerful the society, which helps to promote their social status. Besides, Liu (2018) observed that Chinese speakers in America with Chinese accents are more likely to welcome and accept each other because they are linked to national identities and a sense of belonging, which increases the interactions between immigrants. Dong and Blommaert (2009) have developed a theory, working on the relationship between space, scale, and accent. They suggest that the Beijing accent also catches immigrants’ attention since it symbolizes mandarin or the official language in China, which is beneficial for immigrants to interact with locals and assimilate into their cultures. Zhang (2005) studied the difference in language usage between the professionals in foreign companies and professionals in state-owned companies. She found that phonological variables of [ɹ] sound were not equally used in the market. Professionals in foreign companies frequently used [ɹ] sound to construct their identity as a new social class relating to consumerism, wealth, and citizenship, while their counterparts working in the state-owned companies prefer local accents. That obviously reflects the social stratification caused by various language usages.

However, limited studies focus on the latecomer’s usage of [ɹ] sound and how they used it to build their identities at the same time. This study aims at studying how this specific sound could be employed in linguistic capital and identity creation in Beijing, based on the research on the difference in the sound between insiders and latecomers, and the frequency and accuracy of using this sound. The hypothesis is that latecomers might overcompensate by using it more frequently than insiders, but not always correctly.

Methodology

The experimental approaches used in this study are to analyze the participants’ recordings and interviews. Participants are chosen using “a friend of a friend” since one of the group members is from Beijing. There are 24 people, aged 20 to 40, 12 males and 12 females, who were divided into two groups, insiders and latecomers respectively. Latecomers all have lived in Beijing for more than five years while insiders living here from birth. To make the experiment more general and accurate, other factors such as age and gender were excluded.

Two well-thought-out scripts were given to participants, one is a narrative paragraph and another is a tongue twister. The tongue twister contains a lot of [ɹ] sounds and is very intuitive to observe. However, having a tongue twister may not be enough because they may become defensive and consider adding or removing [ɹ] sounds. Thus, another narrating paragraph was added, which focuses on everyday conversation. From which we can see how they add or subtract [ɹ] sounds without being prepared. After all our observers have read the tongue twisters and narration paragraphs, the recording can then be analyzed to determine how many [ɹ] each person uses and where everyone is using [ɹ]. We try to find out if any interesting phenomena would occur, then investigate the causes of this linguistic behavior. Distributing and asking the participants to read the scripts without their prior knowledge of the research makes their speeches more natural, and that let us find interesting patterns of the locality of the [ɹ] sound.

The following video is an interview about Xiaotong Guan, a native speaker with authentic Beijing accent. The narrating paragraph chosen for our participants was extracted from the video, starting from 2:24 to 2:42. To better understand the Beijing accent and the [ɹ] sound, another video is provided which shows the clear distinction with and without the [ɹ] sound.

Authentic Beijing Accent with the [ɹ] sound – Xiaotong Guan

Master the Beijing Accent with Chinese Stand-Up

Analysis

This study picked one script from our interview of the participant and wrote it in the Pinyin written system, and recordings of one of each participant’s pronunciations among the two groups. The data shows that insiders were adding more [ɹ] sounds than latecomers. Then, two charts show the result of the collected data. To show the differences in the data more visually, this study marked the areas of difference in red (refer to Appendix).

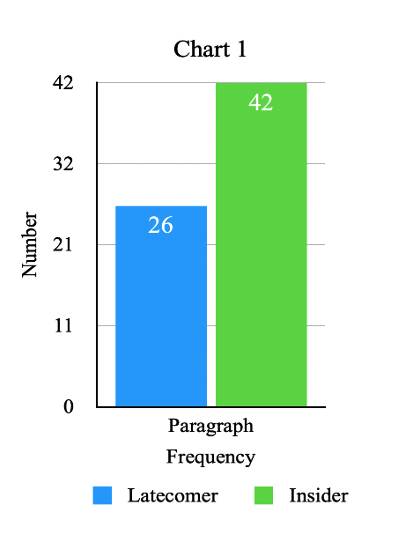

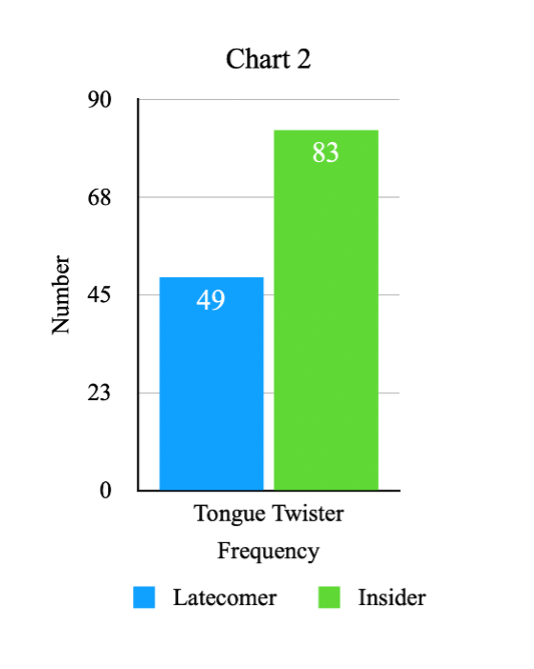

As the two tables above show, concerning the frequency of use of er sounds, in the case of interviews, latecomers used them 26 times however insiders used them 42 times. The percentage ratio is 62% to 100%. This means that insiders used the [ɹ] tone 100% of the time, while latecomers used the [ɹ] tone 62% of the time. In the case of tongue twister, latecomers used it 49 times, but insiders used it 83 times. The percentage ratio is 54% to 93%. The result indicates that in the “standard” case, the number of [ɹ] sound was used should have been 90 because two participants of the insiders did not add the [ɹ] sound where it should have been added, thus resulting in a non 100% value.

Based on this result, the researcher analyzed the data from a positional perspective, this study found two specific examples of the tongue twisters.

| Example 1 | 一串串(means ‘Strings of..’) |

| Yi chuan-er chuan-er | |

| Example 2 | 一段段(means ‘Paragraphs of..’) |

| Yi Duan-er Duan-er |

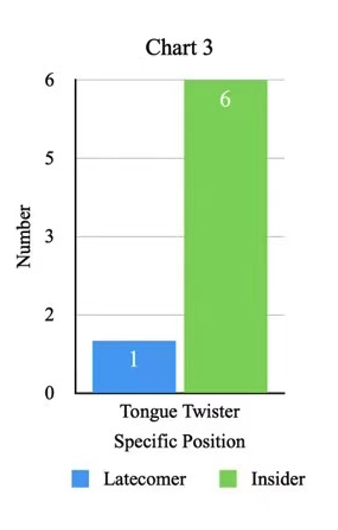

The data shows that two examples have the same pattern position of the [ɹ] sound insertion, i.e., insiders add both er sound to not only the penultimate but also the final word. However, most of the latecomers only add the [ɹ] sound to the final word. The specific data is that only one latecomer has the same insertion as the insiders whereas all 6 insiders add [ɹ] sound at both positions. The percentage ratio would be 17% to 100%, just like the data shows in Chart 3.

Discussion and Conclusion

One of our major findings was that our previous assumptions were tested completely false by data analysis. We were expecting that latecomers use more [ɹ] sounds than insiders while talking about frequency. In addition, we were expecting latecomers would use the [ɹ] sound in incorrect positions. However, the result of the data showed the opposite.

The result from the data of our research appears to go against our hypothesis, which is that we think people who moved to Beijing in later times will employ “erhua” sounds more often, but not in the appropriate position. However, two of our (latecomer) participants stood out to us. The first participant was referred to P1. P1 employed the least of the [ɹ] sound among all of our participants from the two scripts we sent out. The second participant, P2, had employed the [ɹ] sound in an appropriate position and the frequency matched with locals. Due to the extreme differences shown in our data, we proceeded to interview them.

There are different linguistic findings from our interview for the two participants such as nature of personality, identity/language attitude, and linguistic capital. For P1, she is introverted. In the interview, she stated, “ I am more of an introvert, so I don’t like to socialize. I came here with a few friends from my town, and I usually only hang out with them.” A second finding from the interview for P1 is her identity/Language Attitude. The participant expressed that she does not believe in language prestige. Moreover, she is proud of her identity, so she doesn’t think adapting a Beijing accent is essential for her to live there.

Interestingly, our P2 participant expressed a different view on this matter. During the interview with P2, we found out about her attitude towards her Linguistic Capital. The participant believes that adapting a Beijing accent will help her in the future whether it’s for more job opportunities, networking, and better future, education, and an environment for her children. These findings connect with the Ted x Talks video on Youtube “Why your speaking style, like, says about you” by Vera Regan. The research tries to understand why people use the small word “like” in their casual speech. The results of the research communicate that language helps individuals to express their agency and choices. They let people freely identify with a country or a place, and they speak about people’s long-term plans. For P1, she identifies with her hometown and she is proud of her own identity. P2 identifies with Beijingese, thus, she adapts a Beijing accent to express that. She also has thought about her future in Beijing which comply with the long-term plans as in the research stated above.

For this research, since our target population focuses on the Beijing latecomers, studying their frequency of using the [ɹ] sound allows us to learn more about their social status including social identities, recognition, and self-identity construction. According to the main findings, we found that participants who used the [ɹ] sound more frequently are those people who tend to have a long-term plan to stay in Beijing and are willing to be socially reintegrated. In the process of research, we also encounter a few constraints due to the small number of participants which could cause limitations to the research results. First of all, there is actually no way of the “correct” Beijing accent since the geographical location and environment in which one lives will also affect the pronunciation of the [ɹ] sound. For example, people from the east side of Beijing may speak differently from those from the south side, Chongwen may speak slightly differently from Xuanwu, and even people from the same alley may have some minor differences in the use of [ɹ]. Therefore, we did not include an answer key for the “ɹ” sound in both the paragraph and the tongue twister. Instead, we could only take local Beijing participants’ pronunciation as the “standard” way and compare it with the latecomers to analysis amount of “ɹ” sound. The second limitation would be the sample volume. If we are only able to record and interview people in our social circle, the number is defined.

Among these local participants, most of them are the same age as us since we are still students with a fixed network, so classmates and friends while growing up are our first choice. The limited sample due to the lack of the diversity of age, occupation and other aspects caused our participants to not be representative enough. We assume that all latecomers would present similar data as we collected, but we ignore the fact that different social status and the stage of maturity would also possibly affect our hypothesis. Based on this limitation, our future research will pay more attention and develop our research on these social aspects to discover if there are any interesting patterns such as the differences of older people and new generation using [ɹ], as well as how people adopt the sound differently in various fields and positions. Moreover, we are passionate about learning the understanding of various demographic groups towards morphosyntactic functions of rhotacization as well as different expressions such as word choices for Beijing people specifically compared to people from other regions.

References

Dong, J. & Blommaert, J. (2009). Space, scale and accents: Constructing migrant identity in Beijing. Multilingua, 28(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.2009.001

Eckert, P. (2018). Meaning and linguistic variation: The third wave in sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press.

Liu, K. F. (2018). Chinese Speakers in America: Diglossia as Style. essay: critical writing at Pomona College, 2(2), 5.

Xu, Z. (2020). Choosing rhotacization site in Beijing Mandarin: The role of perceptual similarity. University of California, Los Angeles.

Zhang, Q. (2005). A Chinese yuppie in Beijing: Phonological variation and the construction of a new professional identity. Language in society, 34(3), 431-466.

Zheng, M., & Liu, J. (2017, June). Language Attitude and Linguistic Practice of Northeastern Migrants in Beijing, China. In Proceedings of the 29th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-29) (Vol. 2), Michigan State University.

Appendix 1

| Paragraph

|

1

latecomer /insider |

2

latecomer /insider

|

3

latecomer /insider

|

4

latecomer /insider

|

5

latecomer /insider |

6

latecomer /insider |

| 干活儿

ganhuo-er |

1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 |

| 官儿

guan-er |

1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 |

| 从小儿 congxiao-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 | 1/1 |

| 外套儿

waitao-er |

1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 这块儿 zhekuai-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 |

| 出门儿 chumen-er | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 |

| 别这儿

biezhe-er |

-/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| Tongue twister | 1 latecomer

/insider |

2 latecomer

/insider

|

3 latecomer

/insider

|

4 latecomer

/insider

|

5

latecomer /insider |

6

latecomer /insider |

| 哥俩儿

gelia-er |

-/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 脸蛋儿

liandan-er |

1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 |

| 手拉手儿 shoulashou-er | -/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | -/1 | 1/1 |

| 一块玩儿 yikuaiwan-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 一串串儿 yichuanchuan-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 一段段儿 yiduanduan-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 |

| 贪玩儿

tanwan-er |

1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 小猫儿 xiaomao-er | 1/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 |

| 圆圈儿 yuanquan-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | -/1 | 1/1 |

| 小狗儿 xiaomao-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 |

| 庙台儿

miaotai-er |

-/- | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/- | -/1 |

| 小鸡儿

xiaoji-er |

-/- | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | -/- | 1/- |

| 小米儿

xiaomi-er |

-/- | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | -/- | 1/1 |

| 小鱼儿

xiaoyu-er |

-/- | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 水泡儿 shuipao-er | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| Tongue twister | 1 latecomer

/insider |

2 latecomer

/insider

|

3 latecomer

/insider

|

4 latecomer

/insider

|

5

latecomer /insider |

6

latecomer /insider |

| 一串串儿 yichuanchuan-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 一串儿串儿 yichuanchuan-er | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 |

| 一段段儿 yiduanduan-er | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 |

| 一段儿段儿 yiduanduan-er | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 | -/1 | 1/1 | -/1 |