Karen Landeros, Gianelli Liguidliguid, Anna Kondratyeva, Jose Urrutia, Mariana Martin

On the Internet, no one knows you’re a dog…or a catfish. Or do they? On the reality TV show The Circle, contestants are not allowed to interact face to face—instead, they must communicate solely through a voice-activated “Circle Chat.” The anonymity of the show’s format allows contestants to “catfish” as individuals they perceive to be more attractive or likely to be popular, creating a fascinating environment to explore the perceived relationship between language and identity. This study will analyze the digital language devices, flirting habits, and text conversations sent by the contestants themselves to study if gendered language conventions exist and are followed in The Circle. Our research centers around Seaburn, a male contestant, who masks their gender identity by portraying the role of “Rebecca,” a shy, female contestant. We argue that Seaburn/Rebecca constructs their speech using stereotypically gendered language devices and concepts to effectively play the role of a woman. Our analysis highlights which features of online speech are considered to be feminine or masculine, with a specific focus on flirting, and gives insight on how prior knowledge of gendered language impacts how individuals mask their identity online.

Introduction

In our research, we were most interested in researching how contestants who catfish as another gender use linguistic features stereotypically associated with the opposite gender to mask their identity. Gender identity is often characterized by the linguistic patterns one makes use of, and a wide body of existing studies have explored the relationship between language and gender (Lakoff, 1973; Maharaj, 1995; Tannen, 2007). In an influential study, West and Zimmerman (1987) propose that gender is constructed through interactions and that individuals are continually involved in “doing gender.” A catfish would essentially take this idea of “doing gender” to the extreme, behaving and speaking entirely according to stereotypes about what a person of the opposite gender would do or say. The controlled, anonymous environment of The Circle creates a perfect setting to explore how online chat can be used to embody these gender stereotypes and expectations.

Men and women do not speak the same way online, although the ways in which they differ may contradict expectations. For instance, in an analysis of written speech on Facebook, women were “unsurprisingly” found to be warm and polite, but were also more assertive than men (Park et al., 2016). In another study, females were found to be more supportive, agreeable, and emotionally expressive than males in online discussion forums (Guiller & Durndell, 2007). With regards to specific devices used in online speech, females were more likely to use emojis and acronyms, while men were more likely to use hashtags in order to deliver information (Bamman et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2017).

Building off these existing patterns, we also examine the effect of flirting on online interactions. Studies have shown that there is indeed a difference in the flirting techniques used by men and women, which apply regardless of sexual orientation (Clark et al., 2021). For instance, men are more likely to initiate flirting than women (Whitty, 2004). By examining the characteristics of how catfish speak online, both while flirting and throughout the show, we explore how societal definitions of gender influence how individuals adopting false identities construct gender identity and roles within conversations.

Methods

Target Population

The target population of this study included the 14 contestants of The Circle. Our focus is on Seaburn, aka “Rebecca”, because he is the only catfisher in the season who is playing a different gender role. The other catfishers are simply masking as “hotter” versions of themselves.

Methodology

For our study, we utilized quantitative and qualitative data. The former was a preliminary data collection that involved collecting the frequency of emojis, hashtags, and acronyms used in any conversations with at least two interlocutors. This was done in order to see if any patterns of gendered language exist in The Circle. For qualitative data collection, we watched episodes of The Circle to seek out flirtatious conversations between any contestants and then chose a handful of text conversations to transcribe and further analyze. We then examined quantitative factors in flirting such as the gender of the initiator and proportion of sexual content.

Results/Analysis

Data Interpretation

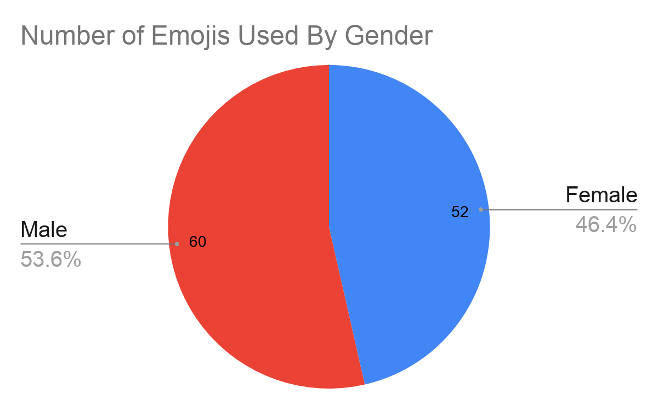

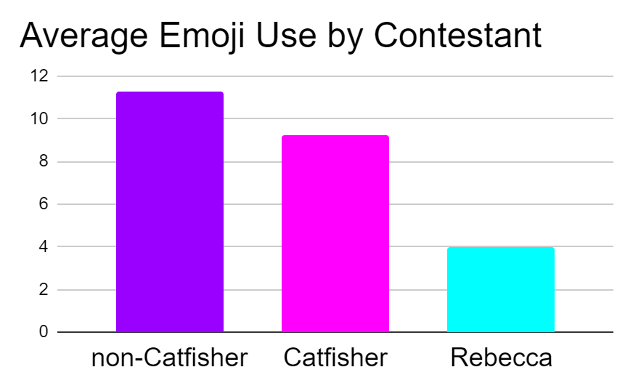

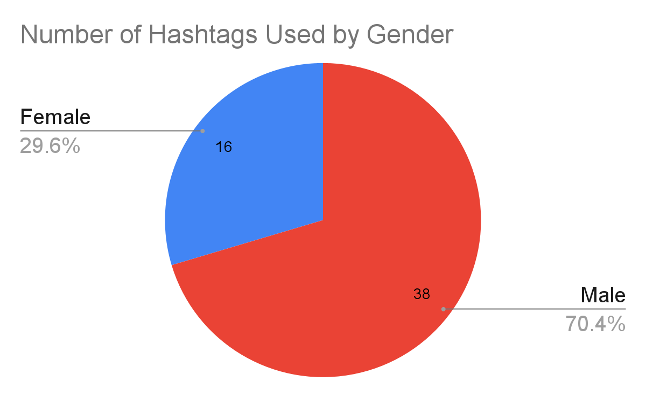

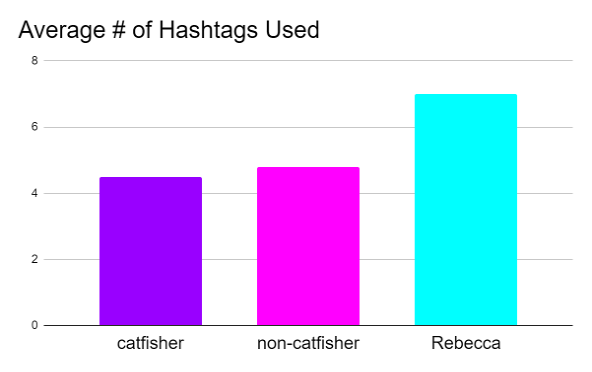

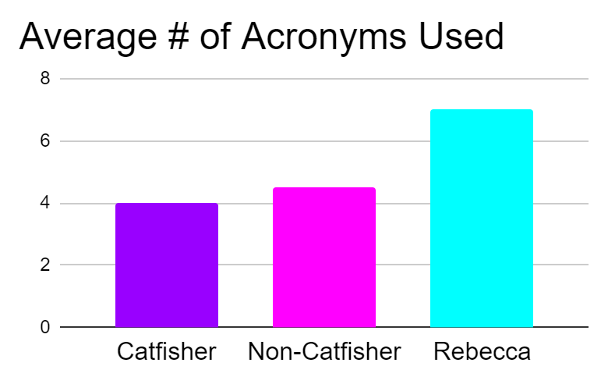

We further stratified the data we collected from the linguistic device frequencies into two different charts. One type of chart highlights the number of occurrences per device between females and males. The other type of chart we created separates the proportioned data into three bars: catfisher, non-catfisher, and “Rebecca,” emphasizing the differences between Rebecca’s language as compared to both catfishers and non-catfishers in the show.

Emojis

In The Circle, emojis are used more often by males than females, as seen in Figure 1. This contradicts prior research on females being more likely to use emoticons than males (Parkins, 2012). Throughout the show, women tended to use emojis more often in same-gender conversations, while males used emojis more frequently in mixed-gender conversations for the purpose of being seen as more expressive by their female peers. The higher emoji usage by men may be a product of the prevalence of mixed and intimate conversations in The Circle, with men being more likely to use more “feminine” speech styles in these environments (Hilte et al., 2020).

Noticeably, as seen in Table 2, Rebecca used emojis significantly less often than both the other catfishers and non-catfishers. This may have fueled other contestants’ suspicions about her “robotic” and overly formal speech.

Hashtags

In online speech, hashtags are used for more than passing on information—they can also convey important emotions to others. In Table 3, we see that males on The Circle use hashtags more frequently than females. Since hashtags also serve as expressive forms (e.g. #YeahBuddy, #paesan), the data falls in line with previous literature that characterizes men’s speech to be more informative than females (Tannen, 2007).

As evidenced by Table 4, there was no significant difference between non-catfishers’ and catfishers’ hashtag usage. However, “Rebecca” used hashtags more than both their catfishing and non-catfishing peers. By using a significantly larger number of hashtags than the average contestant, “Rebecca” is still adhering to the “male” norm that men use substandard versions of language more than females (Holmes, 1992). Thus, as devices like hashtags are found to be more prevalent in male speech, Rebecca’s frequency of hashtag usage detracts from their success in masking their gender identity.

Acronyms

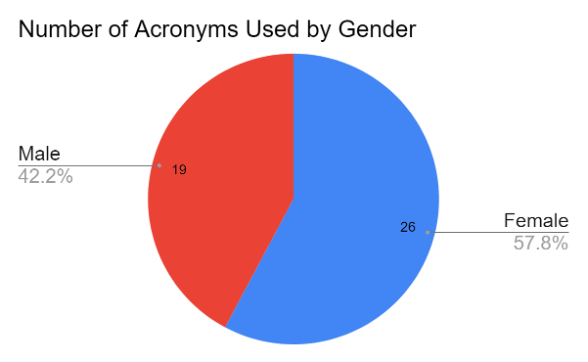

In The Circle, as shown in Table 5 acronyms are often used by females. This falls in line with previous literature, which suggests that acronyms can often serve as female markers in online communications (Bamman et al., 2014).

Since acronyms are an example of a nonstandard device of language, this analysis highlights how innovative female language can be in The Circle. Moreover, the data helped us further understand how the instances of acronyms usage may relate to how females typically act as facilitators in language (Tannen, 2007). For example, within the show there have been instances where the acronym “lol” has served as both a drive to alleviate tension as well as as a transitional phrase to facilitate a conversation by introducing a new topic.

In Table 6, we can see that “Rebecca” utilizes acronyms significantly more often than other contestants. This comparison led us to believe that “Rebecca” associated acronyms with female speech, and purposefully chose to use acronyms throughout their conversations in The Circle.

From the data shown above, we can see that gendered language in The Circle showed some deviations from stereotyped speech. We presume that “Rebecca” employed some markers of female speech based on preconceived notions of what females speak like online, but occasionally failed to adhere to the reality of female speech and mask their identity.

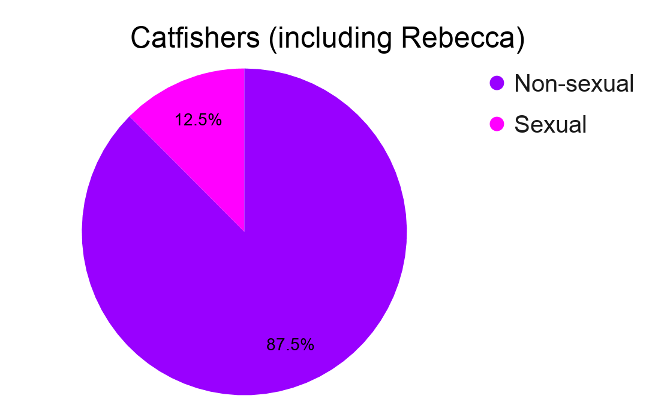

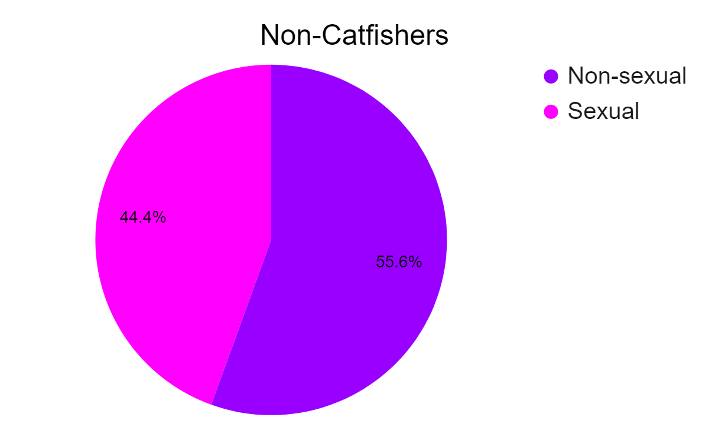

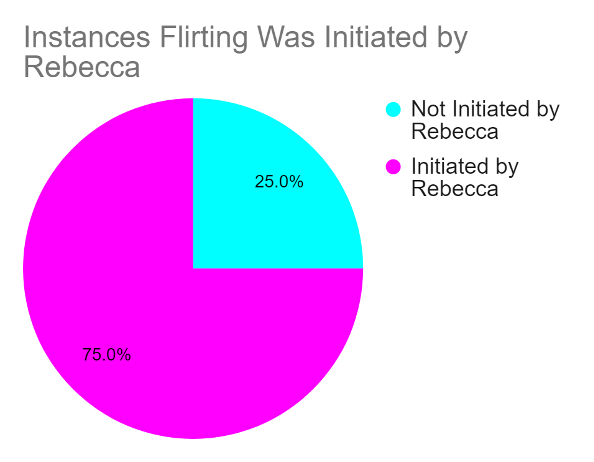

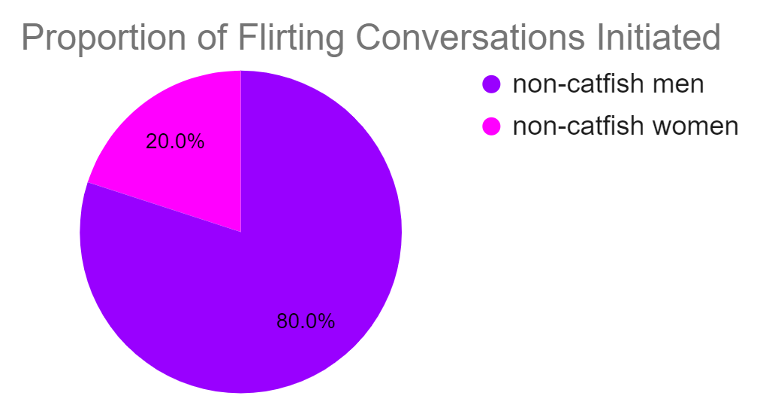

Flirting

The data on flirting (see Tables 7-10 under “Extended Tables”) showed that conversations by non-catfish were far more likely to be sexual in nature. One possible explanation for this is that the catfish did not feel as comfortable being sexual when portraying fake identities, though they did engage in flirting conversations to advance their status in the competition. With regards to flirting initiation, we saw that Rebecca initiated flirting much more often than a typical non-catfish woman, which falls in line with previous literature that shows that men are more likely to initiate flirting (Whitty, 2004). This suggests that “Rebecca” is still following some male flirting norms despite portraying a woman, potentially contributing to the other contestants’ suspicions about her.

Conversation Analysis

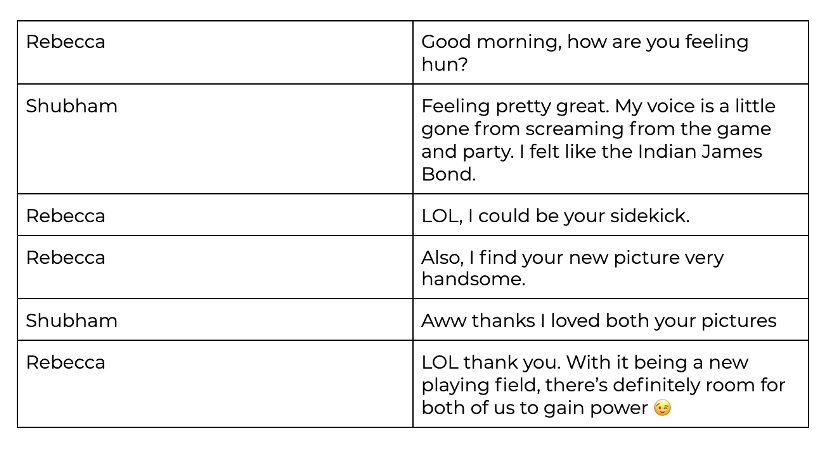

We analyzed three conversations in detail, but for this blog post we will be focusing on two. The first conversation that we analyzed occurred during Season 1 Episode 3, between Shubham (a non-catfisher) and “Rebecca” (a catfisher).

We found that “Rebecca” initiated the flirting first. In most instances (see Table 10), we found that men would first initiate flirting. However in this case, “Rebecca” flirted first in three of out of the four conversations they participated in (see Table 9). Another thing we noted was that “Rebecca” purposefully added the pet name hun at the end of her “Good morning” text. In the episode, Seaburn comments aloud that hun gives a more flirtatious aspect to the message. “Rebecca” also utilized the wink emoji (😉) at the end of this interaction to maintain this flirty atmosphere; this indicates that Seaburn made an effort to use more online emotionally-expressive language devices that are often associated with women (Parkins, 2012).

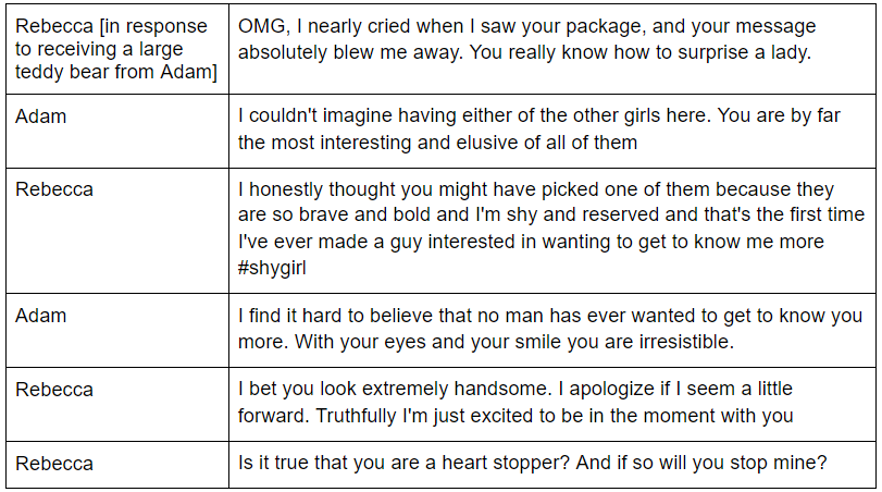

Below is our second example. Catfisher Alex is a heterosexual male catfishing as another heterosexual male named “Adam.” The second catfisher is the focus of our study, “Rebecca”.

When looking at the structure of the conversation, there appears to be an imbalance of turn taking. In the first part of the conversation, “Rebecca” was successful in the use of OMG in the conversation, reflecting previous findings on females being more likely to use emojis (Whitty, 2004). At the end of the conversation, however, we see “Rebecca” use a pick up line which did not ultimately work in their favor, as “men are more likely than women to initiate flirting online” (Whitty, 2004). Due to this gender-masking flaw of initiating a pick up line in the conversation, catfisher Alex became suspicious of Rebecca’s true identity after the conversation. Overall, this conversation proved to be unsuccessful.

Discussion

Ultimately, “Rebecca” was not successful in their attempts to portray a woman through text-based online conversations. Rebecca did use some online language patterns associated with female speech, such as a high number of acronyms, but still spurred suspicions from 5 out of the 6 other remaining contestants by the end of the show. We believe that this could be partially attributed to the fact Rebecca used more hashtags and less emojis than the average female contestant, showing a discrepancy from typical female speech on the show. This discrepancy was also evidenced by her tendency to initiate flirting conversations, deviating from the behavior of other female contestants.

When explaining why they felt Rebecca was “fishy,” contestants named factors such as her over-the-top emotionality, her insincere “shy-girl” persona, and her strangely stilted, formal language (to which a lack of emojis likely contributed to). In addition to not adhering to the realistic patterns of female speech, Rebecca may have put misplaced emphasis on traits stereotypically associated with being feminine, such as shyness or emotionality, which was perceived as inauthentic by the other contestants.

Additionally, we saw no significant difference between the use of emojis, hashtags, and acronyms between catfish who were portraying the same gender and non catfish. This suggests that within the show, catfishers who portray same-gender identities of someone who is more attractive or desirable than themselves do not significantly shift their language in the process. “Rebecca’s” language patterns thus cannot be attributed to the mere fact of changing her identity, but to the fact that “Rebecca” portrayed a different gender in the process.

In our discussion of our results, we must also acknowledge some key limitations of our research. Because this is a reality TV show, the show’s content is highly edited (and possibly even scripted) by producers to create a coherent narrative or to feature the most exciting moments of the series. Furthermore, since the contestants were being constantly filmed, they were also likely to filter their speech. Because the contestants’ speech is filtered, edited, and constructed to fit the needs of reality TV, we do not know if the speech patterns we have access to truly reflect the way that they would speak online.

Another approach to our research relates to concepts shared by actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt in a TedTalk about how social media has ruined our creativity. Instead of striving to collaborate with others and learn from them, Gordon-Levitt says that we see everyone as competition and only want tangible proof of the attention we get (e.g., Instagram followers). Within The Circle, instead of saying that Rebecca adhered to inaccurate stereotypes of female speech, another approach could be to say that Rebecca simply lacked creativity in how to use language due to the competitive nature of the show and the need to get positive attention from others.

In terms of directions for future research, we think that a promising avenue could be exploring catfishers’ language use in text-based conversations. Because The Circle is voice-activated and auto-corrects the contestants’ speech and spelling, the show’s format does not allow for either ordinary spelling mistakes or purposeful alternative spelling (for example, writing “luv” instead of “love”). Exploring how gendered linguistic features are shown through text conversations can further address similar questions, such as which gender is more likely to engage in intentional misspellings, or how spelling errors impact flirting success.

Tables Extended

References:

Bamman, D., Eisenstein, J., & Schnoebelen, T. (2014). Gender identity and lexical variation in social media. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 18(2), 135–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12080

Bryne, S., Harcourt, T., Lambert, S., Lilley, D., Price, S., Fenster, C., Foster, R., & Ireland, T. (Executive Producers). (2020). The Circle [TV Series]. Studio Lambert; Motion Content Group; Netflix.

Clark, J., Oswald, F., & Pedersen, C. L. (2021). Flirting with gender: The complexity of gender in flirting behavior. Sexuality & Culture. doi:10.1007/s12119-021-09843-8

Guiller, J., & Durndell, A. (2007). Students’ linguistic behaviour in online discussion groups: Does gender matter? Computers in Human Behavior, 23(5), 2240-2255. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2006.03.004

Hilte, L., Vandekerckhove, R., & Daelemans, W. (2020). Linguistic Accommodation in Teenagers’ Social Media Writing: Convergence Patterns in Mixed-gender Conversations. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2020.1807853

Holmes, J. (1992). Women’s talk in public contexts. Discourse & Society, 3(2), 131-150. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42887783

Lakoff, R. (1973). Language and woman’s place. Language in Society, 2(1), 45–80. https://web.stanford.edu/class/linguist156/Lakoff_1973.pdf

Maharaj, Z. (1995). A Social Theory of Gender: Connell’s “Gender and Power”. Feminist Review, (49), 50-65. doi:10.2307/1395325

Park, G., Yaden, D. B., Schwartz, H. A., Kern, M. L., Eichstaedt, J. C., Kosinski, M., Seligman, M. E. (2016). Women are warmer but no less assertive than men: Gender and language on facebook. PLOS ONE, 11(5). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155885

Parkins, R. (2012). Gender and Emotional Expressiveness: An Analysis of Prosodic Features in Emotional Expression. Griffith Working Papers in Pragmatics and Intercultural Communication, 5(1), 46-54.

Tannen, D. (2007). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. HarperCollins Publishers.

TED. (2019, September 12). How craving attention makes you less creative | Joseph Gordon-Levitt [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3VTsIju1dLI

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender and Society, 1(2), 125-151. doi:http://www.jstor.org/stable/189945

Whitty, M.T. (2004). Cyber-flirting: An examination of men’s and women’s flirting behaviour both offline and on the Internet. Behaviour Change, 21(2), 115-126.

Ye, Z., Hashim, N. H., Baghirov, F., & Murphy, J. (2017). Gender Differences in Instagram Hashtag Use. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 27(4), 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2018.1382415