Sandra Fulop, David Huang, Yinling Li, Joyana Rosenthal

An important part of college is finding a space to belong. For marginalized students such as LGBTQ women, this can also be the most difficult part. Although there are often groups such as Gay-Straight Alliances or LGBTQ resource centers, these revolve entirely around the LGBTQ identity. But general women’s spaces, such as sororities, are notorious for being less accepting and more exclusive of marginalized identities. This presents an issue for LGBTQ women, who may struggle to create an identity outside of being LGBTQ while avoiding prejudice from groups meant to include all women. Our study focused on the vocabulary choices of LGBTQ women when discussing their own women-centric spaces, specifically Panhellenic sororities or cottagecore communities. We discerned how comfortable and included they felt in their respective spaces and how they felt others perceived them inside and outside that group. We created vocabulary categories to differentiate between inclusive/in-group and exclusive/out-group language, averaged the frequency of use across each group, and compared them. We found that LGBTQ cottagecore women expressed much more comfort in the space they belonged to, while LGBTQ sorority women swept their marginalized identities under the rug and focused on out-group perceptions and stereotypes.

Introduction and Background

LGBTQ college women deserve for women’s spaces to be accepting of their identities. This research concerns how comfortable they are in the groups to which they belong, as measured by which categories of words they use during an interview. The target population was women aged 17-22 who identified themselves as members of women-centric spaces, specifically sororities or cottagecore communities. Cottagecore is a primarily online community catering to LGBTQ identities, which idealizes nature and has a distinct fashion aesthetic. Sororities are a part of Greek life, a space designed for women at universities to meet and support one another through college. Although both these spaces are focused on the wellbeing of women, they are catered to different perspectives. While sororities typically operate under fraternities’ male gaze, cottagecore communities tend to be created by and tailored towards LGBTQ women. We were interested in how the vocabulary of LGBTQ women in these spaces reflected how comfortable they were in their chosen community.

Since individuals’ environments create the framework of how they perceive and are perceived by others (Greco, 2012, pg. 567), we chose two women-centered communities to investigate how the space an LGBTQ woman belongs to affects how they view others and themselves. It has been previously shown that students at campuses without Greek life are more accepting of LGBTQ identities (Hinrichs & Rosenberg, 2002, p. 69), while LGBTQ students in Greek life often feel excluded due to heteronormativity (Fine, 2011, p. 534). LGBTQ students have also faced hostility in residence halls (Evans & Broido, 2009, p. 40), leaving LGBTQ women a small number of communities in which they can feel comfortable. We posited that these women might turn to online communities such as cottagecore, where they can feel more accepted than they would in most in-person spaces. This specific research was informed by a study that showed how women’s words linguistically reflect dependence on men (Lakoff, 1973, pg. 46). We believed that this would be true of sorority women who are counterparts to male fraternities. Much of their identity as a sorority woman likely reflects the opinions and perspectives of those men in fraternities. However, because cottagecore communities have no reason to focus on such a direct male presence, we hypothesized that those women’s vocabulary would not corroborate Lakoff’s results. There is a gap in the literature comparing on-campus women’s spaces to off-campus women’s spaces. However, because cottagecore originated as a safe space for women and those identifying as LGBTQ, we hypothesized more vocabulary surrounding comfort and inclusivity within this community. This directly contrasts sororities, where we expected that LGBTQ women would discuss more exclusion and focus more on out-group perceptions.

Methods

We interviewed two LGBTQ women, each in cottagecore communities and sororities. The researchers asked each participant the same set of interview questions about their identities and perceptions, how represented they felt in their spaces, and how others on campus viewed them and their communities. We divided inclusive and exclusive languages into specific categories, such as stereotyping and out-group vocabulary, and averaged the frequency of each category’s use between the two members of each group, then compared them to the other group’s use.

Results and Analysis

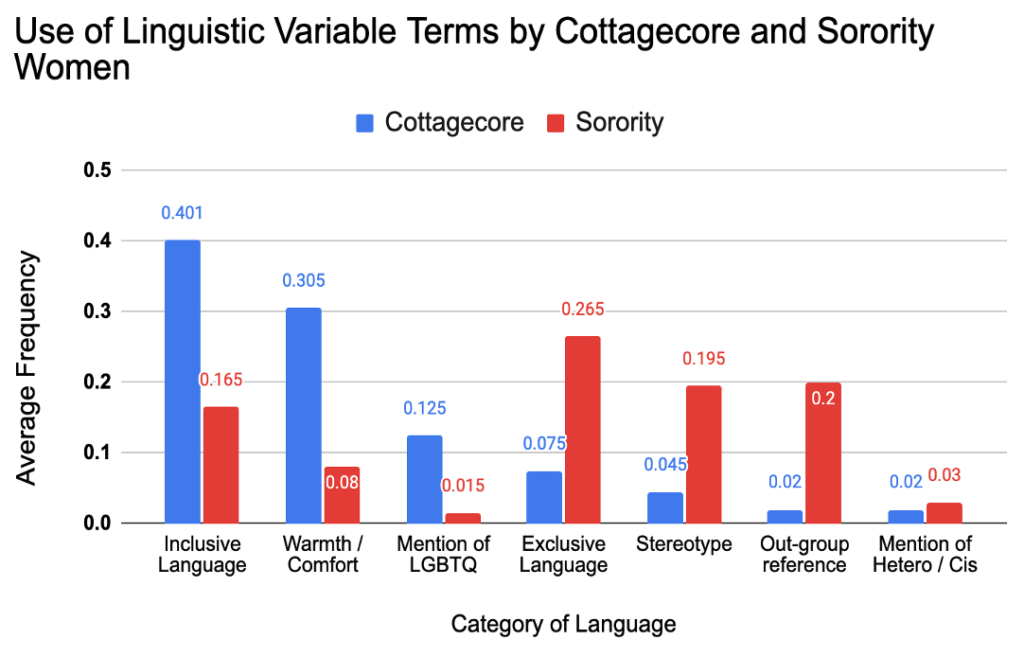

To analyze the linguistic data we collected, we created seven different language categories to analyze what each woman said about the community to which she belongs. The first was the inclusive language, which was any word or phrase representing inclusion. For example, referring to their space as a “community.” The second was warmth/comfort, which was a word or phrase referencing a feeling of safety or happiness in their space. Examples used were “comfortable” or “kind.” The third was any mention of the LGBTQ community, such as “lesbian” or “LGBTQ community.” These were the categories that demonstrated inclusivity and comfort in their space.

The more negative or exclusive categories were the following: exclusive language, any word or phrase representing exclusion of a particular person or group of people, such as “bigotry.” The next was stereotyping or labeling, any language referencing or creating a stereotype or label. Some examples we heard were “dumb party girl” or references to a “curated image.” The next was out-group language, anything referencing a group’s perception that the woman herself did not belong. Some examples were “fraternities” and “art hoes.” The last category under exclusive language was mentions of heterosexuality or cisgender people. This is not a negative concept, but since we measured comfort and confidence in LGBTQ women, we looked for positive references to their own identities rather than those of other people. We noted mentions of homophobic exclusivity. These references included phrases such as “heteronormativity” or “cisgender ideals.”

In Graph 1, each category is represented by a double bar graph for the two groups’ average frequency of use. We calculated the number of words from a specific category to the total words they used in every category and averaged it between the two women in each group. We found that cottagecore women used inclusive language at an average frequency of .401, and sorority women at .165. Cottagecore women used warmth/comfort language at an average frequency of .305, sorority women at .08. Cottagecore women mentioned the LGBTQ+ community at an average rate of .125 and sorority women at .015. Cottagecore women used exclusive language at an average rate of .075, and sorority women at .265. Cottagecore women mentioned stereotypes and labels at a rate of .045, and sorority women at a rate of .195. Cottagecore women used out-group references at an average of .02 and sororities women at .2. Lastly, we found that cottagecore women mentioned heterosexuality and cis-gendering at a rate of .02, with sororities at .03.

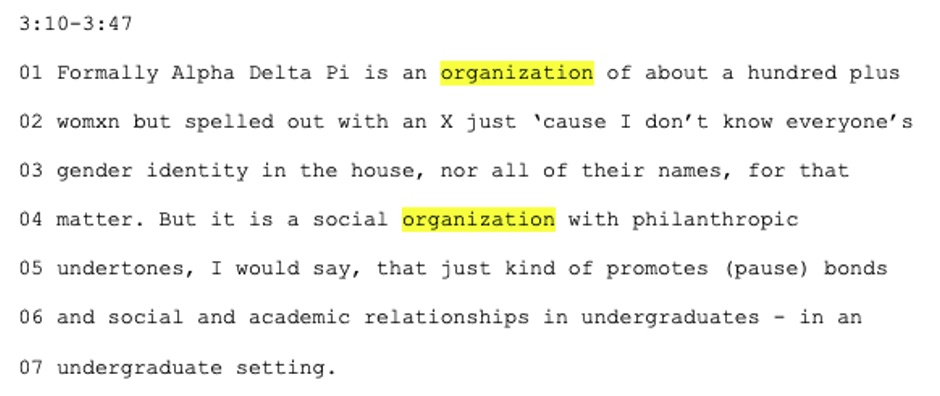

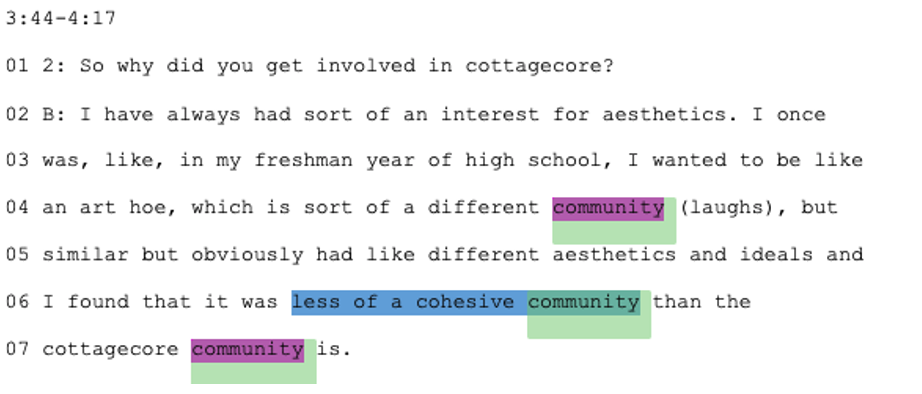

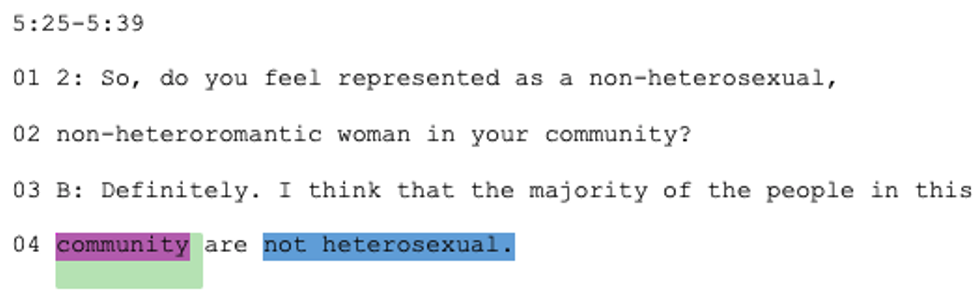

We also noted phrases that did not fit into a specific inclusion/exclusion category but were telling about the interviewees’ perceptions. One example is that, when we interviewed the participants, we referred to both cottagecore and sororities as “communities” explicitly. However, the sorority women consistently referred to their space as an “institution” or “organization” (Fig. 1), whereas the cottagecore women-only referred to their space as a “community” (Fig. 2). We found it interesting that the sorority women chose to use words that, instead of indicating closeness to the space they belonged to, were indicative of something separate from themselves.

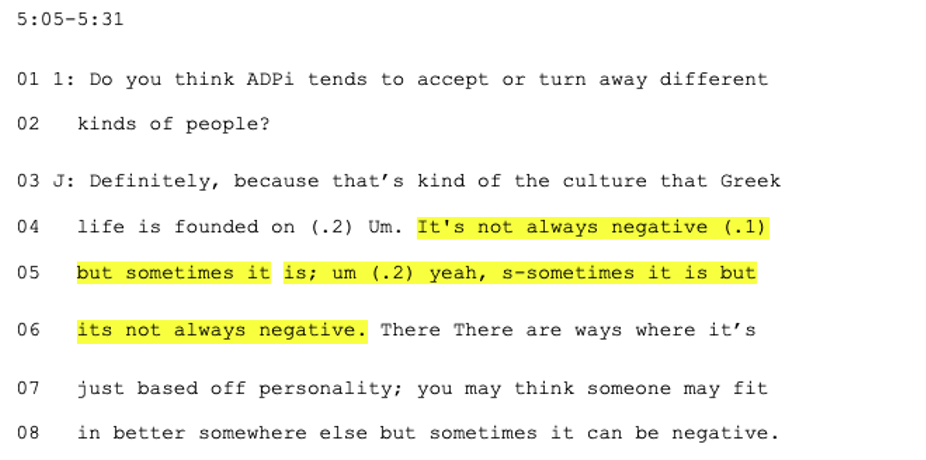

The sorority women were also more hesitant to critique their space. For instance, when asked about the exclusivity of their space, one sorority woman stated the following:

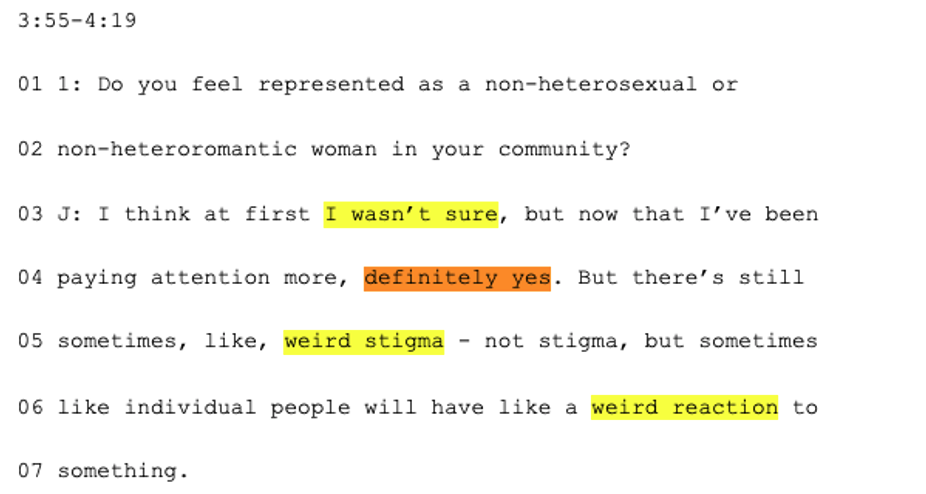

Additionally, both sorority women answered the question regarding a feeling of acceptance and representation as an LGBTQ woman in their space with uncertainty (Fig. 4). In contrast, the cottagecore women answered the same question with definitive yeses (Fig. 5).

Finally, we concluded that cottagecore women were much more comfortable in their community than the sorority women were. They used inclusive language at almost 2.5 times the rate of sorority women and warmth/comfort language at about 3.8 times the rate of sorority women. They also referenced out-groups much less and tended not to stereotype others. Sorority women used exclusive language at 3.5 times the rate of cottagecore women and referenced out-groups (usually groups relating to men such as fraternities) at ten times the rate of cottagecore women.

Discussion and conclusions

Based on our data, the sorority women were much more focused on others’ perceptions of them, likely because they are conditioned to focus on an image as counterparts of male fraternities. In contrast, the cottagecore women felt freer to focus on their own safe space within their inclusive community. We concluded that cottagecore women’s common mentions of being LGBTQ show that they are more comfortable than sorority women, who acknowledged heteronormativity and never mentioned being LGBTQ after the initial statement of their identity. This demonstrated that cottagecore women are less likely to internalize bias against the LGBTQ community, while sorority life normalizes these biases. Repeating this study with larger sample sizes at different universities might also yield more nuanced information regarding regional and cultural differences concerning this phenomenon.

Following this, we believe that college-age LGBTQ women need more spaces geared towards them to feel comfortable and safe because sororities do not seem to give LGBTQ women the room to explore and express their LGBTQ identities. Colleges should look towards cottagecore as a model for on-campus casual interactions between LGBTQ women in a space that is acceptable but not focused on being LGBTQ. As campus communities try to be more inclusive of all identities, it could also be beneficial for sororities to undergo more implicit bias and diversity training.

Although our research focused on LGBTQ women because we assumed marginalized identities would express more apparent feelings of exclusion, it could be that women in sororities might speak a certain way due to the space to which they belong. It might not be related to their sexual identity. For further research, it would be informative to look at whether there is a difference in how straight women and LGBTQ women, both in sororities, use these same vocabulary categories.

References

Evans, N. J., & Broido, E. M. (2002). The Experiences of Lesbian and Bisexual Women in College Residence Halls. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 6(3-4), 29-42. https://doi.org/10.1300/J155v06n03_04

Fine, L. E. (2011). Minimizing heterosexism and homophobia: constructing meaning of out campus LGB life. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(4), 521-546. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.555673

Greco, L. (2012). Production, circulation and deconstruction of gender norms in LGBTQ speech practices. Discourse Studies, 14(5), 567-585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445612452229

Hinrichs, D. W., & Rosenberg, P. J. (2002). Attitudes Toward Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Persons Among Heterosexual Liberal Arts College Students. Journal of Homosexuality, 43(1), 61-84. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v43n01_04

Lakoff, R. (1973). Language and woman’s place. Language in Society, 2(1), 45-79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500000051