Jessica Chen, Jean Maynard, Naomi Muñoz, Daisy Terriquez

“I’m sorry, I’m taking accountability” is a phrase that may sound familiar to those who frequent the internet. This is referencing the category of YouTube videos known as the “apology video,” where, as the name suggests, influencers post videos of themselves apologizing for actions that caused them to be “canceled.” In this blog, we examine if these apology videos share any patterns in their word choice and behavioral manners and if certain key words and phrases contained in these videos have become recognizable to audiences and associated with this style of video. This study was conducted in two parts: (1) analyzing 10 different apology videos posted to YouTube to map the commonalities found in word choice and gestures and (2) a two-part survey to deduce if participants could identify apology videos based solely on a provided comment or phrase. With this entry, we hope our findings can further the understanding of internet language, as well as promote conversations of media literacy, social advocacy, and mental health surrounding internet spaces.

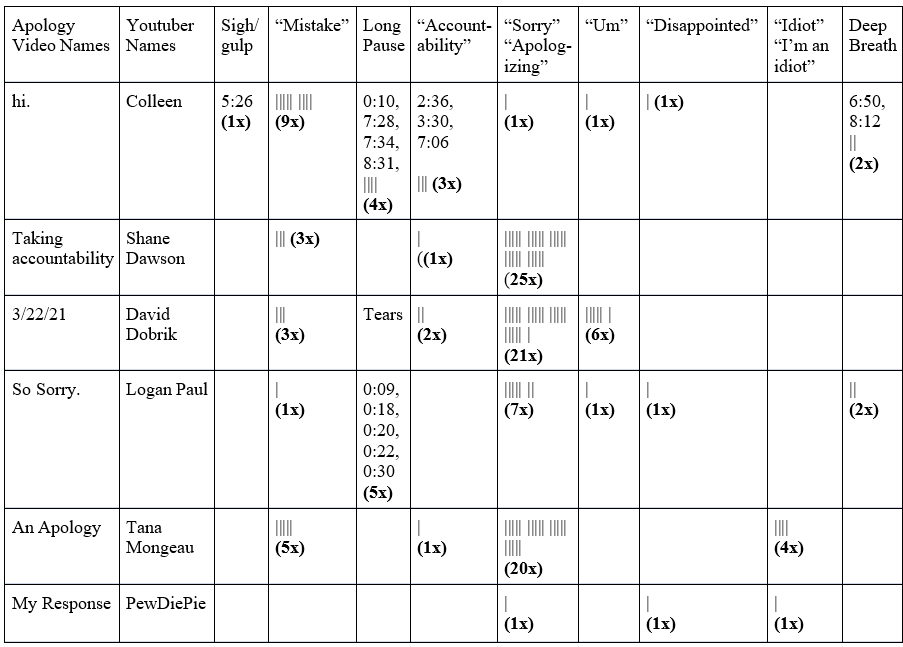

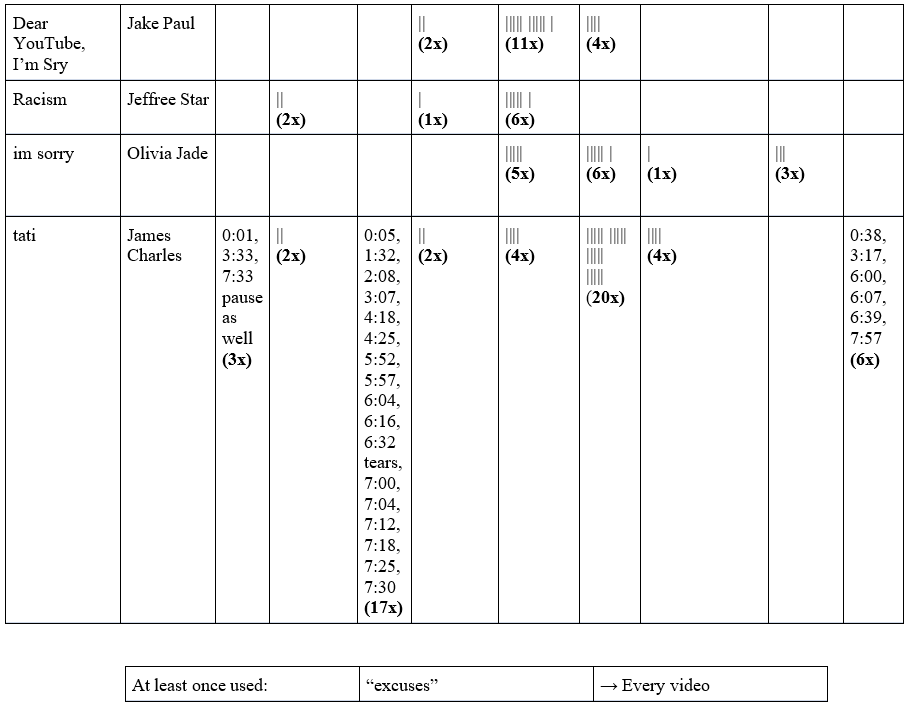

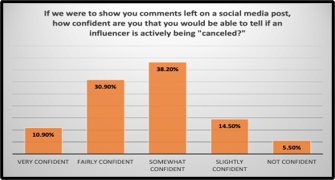

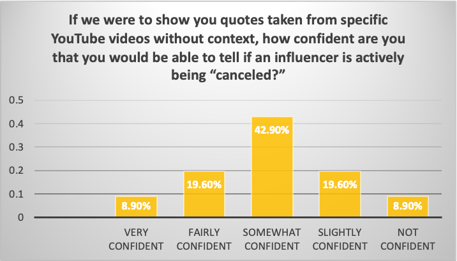

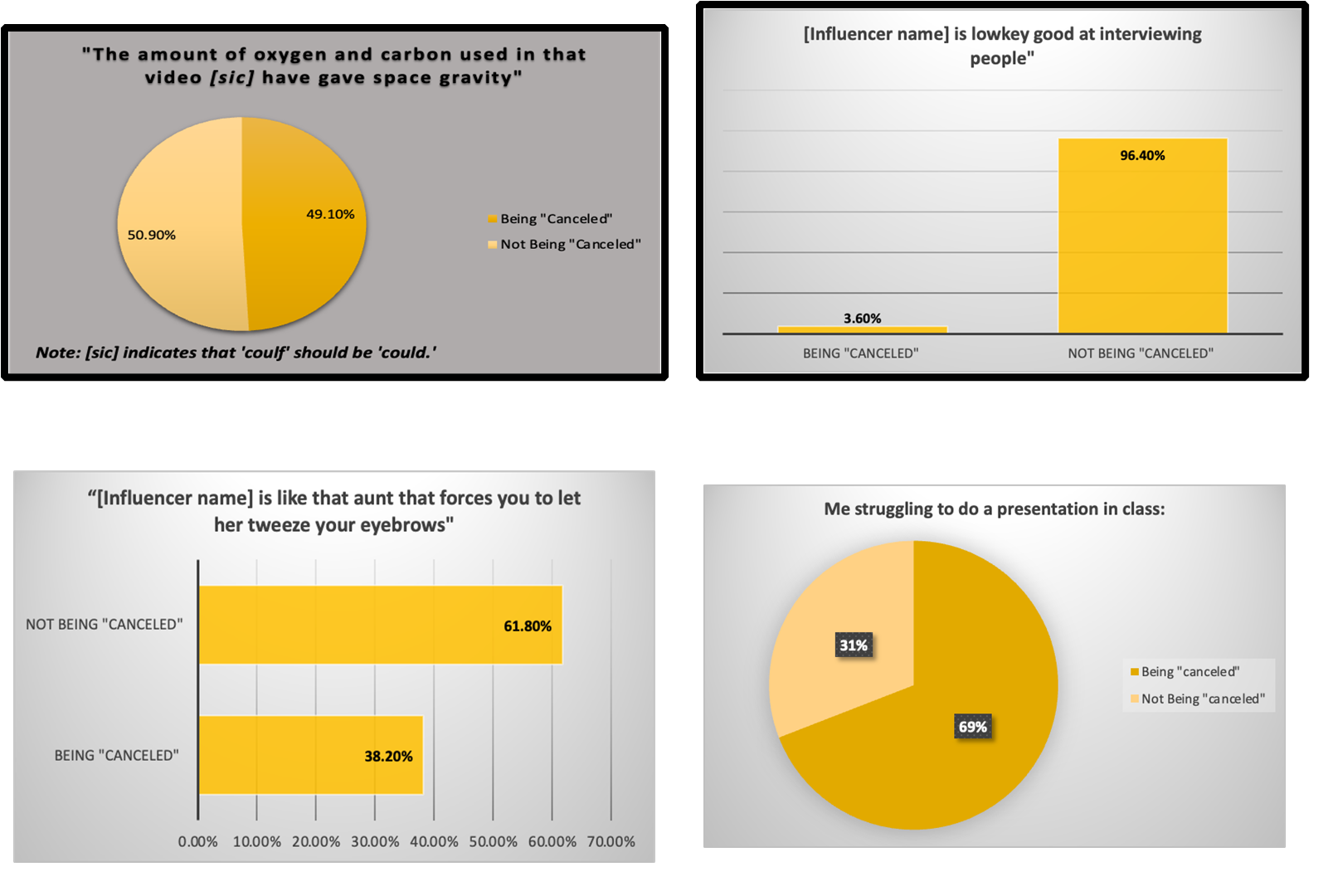

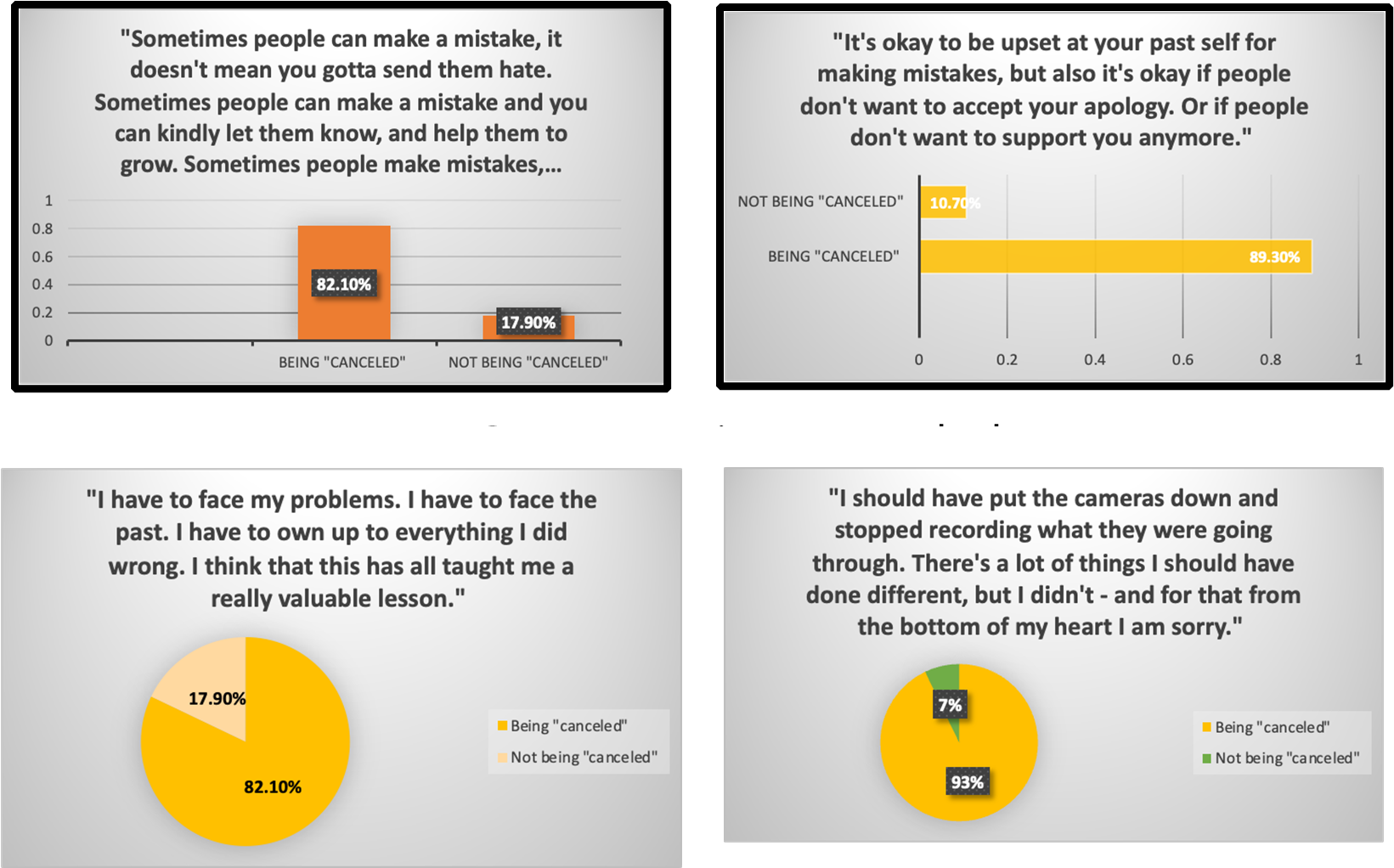

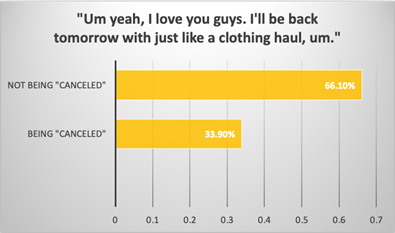

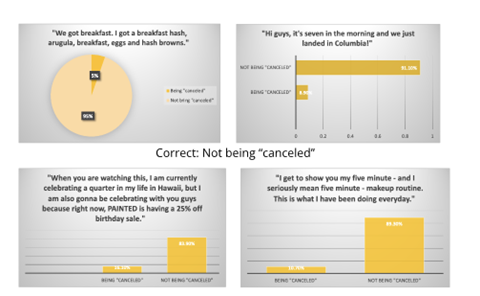

Introduction and Background With the globalization of technology, the ability to connect with a broad audience and build a large following has become readily attainable. Today social media platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, Twitter/X, and Instagram have facilitated the emergence of “influencers,” individuals who regularly post content on the internet and have managed to captivate a large following by sharing their daily lives, opinions, and thoughts. However, with such a large social media presence comes an increased possibility of every one of one’s actions being perceived and criticized by individuals who do not share similar morals or values. Consequently, it has become quite common to open social media apps to see yet another influencer on camera sighing and apologizing for an alleged act of misdemeanor they are being framed with. Essentially, this has made the online “celebrity apology” become so common; it has given rise to “cancel culture” and with it, the “YouTuber apology” category of videos. The concept of “cancel culture” first emerged in the early 2010s and gained significant traction in the mid to late 2010s. Across social media platforms, “cancel culture” is defined as the practice where numerous people express their disapproval and withdraw support from a particular individual or brand (Roos, 2020). It encourages current supporters to “flock away” from influencers who have engaged in actions that are not deemed socially acceptable (Lewis & Christin, 2021). Cancel culture originated on Twitter/X with the intent to bring awareness and accountability to celebrities who have committed social injustices, dating back to movements like #MeToo, but has since been colloquially used to refer to the mass bullying and harassment of creators (Roos, 2020). Cancel culture, with its “canceled” celebrities, gave rise to the category of videos on YouTube known as the “Youtuber Apology Video.” This is when a content creator records and posts a video of themselves apologizing, expressing their remorse for their misconduct, and asking their audience for forgiveness (Karlsson, 2020). As content creation is a livelihood for many of these influencers, losing monetary support due to overwhelming criticism can be a source of emotional and financial distress, motivating these influencers to release an apology video in an attempt to repair their public image (Goanta & Ranchordás, 2019). Interestingly, although the reason behind each of these videos may differ, there is reason to believe that many of them contain similar content. In their study analyzing various public celebrity apologies, Cerulo and Ruane (2014) found patterns of apology techniques that many celebrities employed in their statements. This looked like 27% of celebrity apologies containing “evasion” statements where they avoid responsibility, 29% of apologies having “action-ownership” statements where they acknowledge an action, and 32% having “mortification” statements in which the celebrity acts mortified by their own actions (p. 130-135). Though this study predates the rise of many famous YouTube apologies, it suggests a possible pattern that past celebrity apologies may have formed, which proved to be a useful foundation for our research. Although we did not utilize the same categories as Cerulo and Ruane (2014) and opted to find our own keywords, our research aimed to expand on what patterns, if any, could be found in this new form of celebrity image repair. While research on “cancel culture” exists, our study attempts to address the research gap on both the precise language employed by YouTube content creators’ apologies, as well as how the individual viewers react to and process the content found within these videos. We believe that most research has not addressed the possible relationship between language used by the influencer and how the viewer interacts with it. This research will thus focus on the language used in influencers’ apology videos when they are being “canceled” by the general public. With a focus on Generation Z (Gen Z) and Millennials, the two generations who grew up with technology as an integral part of their daily lives (Serbanescu, 2022), the two research questions that arise are the following: First, can Gen Z and Millennial individuals tell whether an influencer is being canceled solely based on the language being used? Second, does an influencer change their speech patterns or behavioral gestures when they are being canceled? Our aim was to compare the reactions of Gen Z and millennial individuals to language and behavioral gestures used by an influencer when they are being canceled versus when they are in good standing. We hypothesize that when an influencer is aware that they are being canceled, they will engage in specific behavior and speech patterns. Further, we hypothesize that Gen Z and Millennial individuals will be able to tell without context when an individual is being canceled simply by reading comments or quotes with keywords associated with cancel culture. Methods To capture commonalities among influencer apologies, we started by compiling 10 YouTube apology videos, all involving YouTube creators who had amassed at least one million subscribers at the point they were canceled (See Image A). Even before this, we started by coding James Charles’ apology video titled “tati” and looked out for words and gestures that were constantly repeated. Based off that initial coding, we created a data chart with eight different keywords (“excuses,” “mistake,” “accountability,” “sorry,” “apologizing,” “um,” “disappointed,” and “idiot”) and four gestures (sighs, gulps, long pauses, and deep breaths) and continued meticulously examining and coding each video to pull out every instance of any of the keywords or gestures. In other words, each video received a tally of how many times these phrases or gestures appeared in the video. Gestures such as sighs and gulps, deep breaths, and long pauses were important in order to grasp an idea about the important factors, other than utterances, that can act as non-verbal communication methods and accompany the keywords to further emphasize the presence of “cancel culture.” Due to the important existence of gestures, we also operationalized “disappointment” as when an influencer simultaneously looks downwards and squints their eyebrows. To continue our data collection, we created Survey 1, a survey that tests whether or not people know which influencer is being “canceled” based on comments from their YouTube videos (See Image B). With four survey questions in total, two contained comments from normal videos, while the other two contained comments from apology videos. These comments were chosen specifically from James Charles’ YouTube videos, as he was the initial focus for this research; however, future studies should expand to other influencers’ comments to have more variety. The comments were selected randomly, but we intentionally searched for comments that seemed more positive, had humor, and contained little context. This survey was largely utilized to supplement the overall definition of “cancel culture” by assessing Gen Z and Millennials’ topical understanding of it. Furthermore, another survey, known as Survey 2, was created with the same test; however, it was based on utterances from both apology and normal videos of the influencers (See Image C). Among the several questions that were given in this survey, we deliberately crafted a suitable set of utterances from apology videos that involved our specific keywords to test if people associate those keywords with “cancel culture,” making it one of the most crucial parts of our data collection. By extracting quantitative data from the YouTuber apology videos and surveys, we were able to analyze what specific words and linguistic styles Gen Z and Millennial individuals deem to be associated with apologies and “cancel culture.” Results and Analysis We can start by examining the data table that quantifies specific keywords uttered in the 10 apology videos and non-verbal communication methods that supplemented those keywords (see Table 1). Table 1 displays the heavy use of “sorry” and “apologizing” in all of the apology videos, as well as the common effort to include mentions of “accountability” and making “mistakes.” Some YouTubers occasionally described themselves as feeling “disappointed” in themselves or feeling like an “idiot.” Most importantly, it was extremely common for them to use the word “excuses” in their apology videos. As for gestures, long pauses (with occasional tears) were the most frequent and seemed to dramatize the keywords. Moreover, four graphs were created to illustrate the results of Survey 1, and eight graphs were made for Survey 2. Among our 55 Gen Z and Millennial survey takers, we gauged the amount of those who felt confident in their ability to tell if an influencer is actively being “canceled,” to which most replied they were somewhat confident (See Tables 2a and 3a). Table 2b exhibits the quantified survey results from Survey 1 that involve two comments from when an influencer was actively being “canceled” and two comments from when they were not. For Comment #1, answers were roughly split; however, there were fewer individuals who could determine that the influencer was actually actively being “canceled.” For Comment #2, #3, and #4, most individuals were able to determine the existence of “cancel culture.” Subsequently, Tables 3b and 3c display results for Survey 2, specifically for utterances derived from our chosen apology videos and that contain our significant keywords. Individuals were more likely to be correct and be able to tell that an influencer was actively being canceled; however, Table 3c illustrates that more than half of the survey respondents were unable to determine whether an influencer was actively being “canceled” based on the keyword “um.” Individuals were also more likely to be correct when determining a normal utterance where there were no keywords present (see Table 3d). Discussion The current investigation attempts to fill these major gaps within the research by examining cancel culture from a linguistic perspective. Data gathered from YouTube suggests that the comments left on videos where an influencer is being canceled tend to be harsh and demeaning, aiming to publicly shame and bully the creator. The negative language used in the comment section appears to prompt the creator to upload a YouTube video where their language appears to be apologetic, while their behaviors simultaneously portray disappointment and shame in themselves. Since an influencer is aware that they are being canceled, they resort to the use of language that has proven to be effective when crafting an apology. The findings from this investigation indicate that, in what appears to be an act of desperation to put an end to negative comments and find themselves in good standing with the YouTube community, influencers often resort to the use of the keywords discussed above. Their language quickly shifts from casual everyday language to words that show that they deeply regret their actions and are willing to take accountability. In Survey 1 (See Table 2b, #1), a comment without context was purposefully chosen in order to test what most respondents think about “cancel culture” comments off the bat. Without context, it is difficult to tell what a comment is specifically referring to. Therefore, our results suggest that there are differences in how individuals view internet language, and it in turn influences whether they think an influencer is being “canceled” or not. In other words, because Comment #1 had no negative keywords and Comment #4 did (“struggling”), it hints that people associated the negative word with “cancel culture,” and therefore, “cancel culture” has this negative linguistic connotation to it. It is also important to note context in our Survey 2 results. When choosing utterances for our survey (See Tables 3b and 3d), we intentionally included utterances about breakfast, trips, sponsorships, and makeup routines, all contexts that are far from the idea of “cancel culture” and negative linguistic aspects. The context completely juxtaposes the utterances from apology videos (See Table 3b) because they are missing the “cancel culture” keywords. A very important finding in Table 3c suggests the importance of those negative associations. In this example, the apology video utterances are more ambiguous than others, especially with the inclusion of “um.” We include the keyword “um” because although it is an extremely common human utterance, it acts as a neutral keyword and requires more context. Most people responded with “Not being canceled,” suggesting that due to the absence of an explicitly negative keyword, respondents were not naturally drawn to viewing it as an apology video utterance. Previous studies have primarily focused on exploring the psychological effects that cancel culture has on the individual that is actively being canceled. Such studies suggest that while cancel culture originated with good intentions — to hold individuals accountable for socially unacceptable actions — the psychological effects of cancel culture are oftentimes negative and include: social isolation and loneliness, depression, low self-esteem, and constant fear and anxiety (Berryman & Kavka, 2018). Although these findings add to the existing body of research, they also highlight gaps and consequently lead to further research questions: Why does cancel culture lead to these negative psychological states of mind? Does language play a role in cancel culture? Can cancel culture be viewed from another point of view? Essentially, examining cancel culture from a linguistic perspective adds to the existing research because these findings can be tied back to a psychological perspective and begin to answer these questions. Understanding that the language associated with cancel culture is oftentimes negative and harsh, instead of critical and constructive, allows us to understand why the influencers who are exposed to cancel culture are negatively impacted psychologically. Looking at cancel culture from different lenses can lead us to discovering new findings, but considering the importance of language to our everyday lives, a linguistic analysis is an effective way to begin. References Berryman, R., & Kavka, M. (2018). Crying on YouTube: Vlogs, self-exposure and the productivity of negative affect. Convergence, 24(1), 85-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517736981. Cerulo, K. A., & Ruane, J. M. (2014). Apologies of the Rich and Famous: Cultural, Cognitive, and Social Explanations of Why We Care and Why We Forgive. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(2), 123-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272514530412. Goanta, C., & Ranchordás, S. (Eds.) (2019). The Regulation of Social Media Influencers. Edward Elgar Publishing. Elgar Law, Technology and Society series. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3457197. Karlsson, G. (2020). The YouTube Apology; Analysing the image repair strategies and emotional labour of saying sorry online. Malmö University, School of Arts & Communication K3. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1483089/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Lewis, R., & Christin, A. (2022). Platform drama: “Cancel culture,” celebrity, and the struggle for accountability on YouTube. New Media & Society, 24(7), 1632–1656. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221099235. Roos, H. (2020). With(Stan)ding Cancel Culture: Stan Twitter and Reactionary Fandoms. Muhlenberg College. https://jstor.org/stable/community.31638145. Serbanescu, A. (2022). Millennials and Gen Z in the Era of Social Media. In A. Atay & M. Z. Ashlock (Eds.), Social Media, Technology, and New Generations: Digital Millennial Generation and Generation Z (pp. 61-77). Lexington Books. All Videos Used for Analysis Ballinger, C. [Colleen Vlogs]. (2023, June 28). hi. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ceKMnyMYIMo. Dawson, S. (2020, June 26). Taking Accountability [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ardRp2x0D_E. Dobrik, D. (2021, March 22). 03/22/21 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lB734hc89x8. Dunsmorel, J. (2019, May 13). James Charles Tati re-upload [Reposted Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3Ukl4l_LM8. Jade, O. (2018, August 6). im sorry [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LAJArLC6v70. Kjellberg, F. [PewDiePie]. (2017, September 12). My response [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cLdxuaxaQwc. Mongeau, T. (2017, February 17). An Apology [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fazh9Lm1kDE. Paul, J. (2017, June 3). Dear YouTube, I’m sorry…. [Video]. YouTube (min. 10:36-17:43). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C45-1rf65PU. Paul, L. (2018, January 2). So Sorry. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwZT7T-TXT0. Star, J. (2017, June 20). RACISM. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Su6FeI7lHVg. Related Resources Languaged Life post: Celebrities and Controversies: What Works and What Doesn’t in Apology Videos Interesting interactive graphic on the history and patterns of apology videos: https://pudding.cool/2020/01/apology/