Chen Chang, Jennifer Eom, Kanghyun Lee, Lavinia Lee, Cynthia Ortiz

“I can make the PowerPoint, but, uhmm…can you do the oral presentation for me?”

Due to pronunciation unfamiliarities in the English language, ESL (English as Second Language) speakers may sometimes develop apprehensiveness and insecurities towards their oral speaking skills. This is not an intrinsic response but rather an extrinsic consequence — people in the United States tend to perceive ESL speakers as less credible and less intelligent compared to standard American-accented English speakers. As the number of Korean international students in the United States increases over time, it is observed that some of the Korean ESL speakers are facing such discrimination as well. Hence, this project contains two parts of survey to serve the purpose of collecting and analyzing data relating to how Korean ESL speakers in the United States are being perceived; as well as to demonstrate the difference in credibility and intelligence level that “having an accent” can cause. Although this research project may be conducted on a relatively small scale and there exist some limitations and potential biases; the results may come out to be less significant than it is projected to be — there is little difference between a native speaker and a Korean ESL speaker in terms of perceived intelligence level and credibility; however, the scale of such inequity currently happening in this society is inevitably, very substantial.

Introduction

The U.S. is a concoction of many distinct cultures and languages as a result of settlement by non-natives and international students (Wharton University of Pennsylvania, 2017). There are also a variety of different English accents found in the U.S as a result of the people all over the world that are learning English. As of fall 2018, the percentage of public school students in the United States who were English as a second language speakers was 10.2 percent or 5.0 million students (National Center for Education Statistics). However, this does not mean that the U.S is free from prejudice and bias.

Sometimes accented speeches are harder to process and understand. When people are perceiving accented speech, they encounter difficulties that will reduce the “processing fluency”, as reported by Lev-Ari et al. (2010). Yet instead of simply perceiving the accented speech as harder to understand, people tend to perceive it as less truthful. One of the major groups of speakers affected by this is Korean speakers who grew up in a Korean-speaking environment. They tend to speak Korean-accented English due to not having been as exposed to standardized English (Linguistic Society of America). And so, the ESL Korean speakers could be perceived as less credible and intelligent, simply because they struggle with pronouncing some sounds in English and causing native speakers to have a harder time processing their speech.

The present study seeks to better understand how Korean ESL speakers who have Korean-accented pronunciation may be treated differently than standard American English speakers. This study explores whether listeners will perceive Korean accented English speakers as less favorable when compared to standard American accented English speakers.

Background

In Rickford & King’s (2016) study, a leading prosecution witness who spoke in African American Vernacular Accent (AAVE) had her crucial testimony dismissed. What led to this is that her speech was deemed incomprehensible and not credible. Unfortunately, this is not an unfamiliar experience for many people, including ESL Korean speakers. There are more than 81,000 Korean students studying in the United States, which accounts for 7% of the US’s international students population as stated by the United States Homeland Security (2015). Any non-native English speaker could face prejudice and unfair experiences in our society due to certain linguistic features that ESL speakers have (Lippi-Green, 2012).

How was this study designed?

This research project focused on two parts: how non-English speakers are perceived socially about their intelligence level and credibility, and the perception of English speakers on Korean ESLs. The research was done by Google survey, and since our group members are all UCLA students, the participants were recruited on the campus. The survey was in two parts. The first part of the survey is generally asking the participants’ demographics and any experiences of racial discrimination. In the second part of the survey, the first thing that we did was ask their pre-existing bias about specific jobs’ credibilities and intelligence levels. To collect these data, we used the Likert scale to rate how they feel about teachers, lawyers, and doctors generally about their credibility/ intelligence level should be. Then we asked the participants to listen to three different recordings of reading English scripts by three different accents: Native English speaker, Korean ESL speaker who has a lot of Korean accent in it, and the third speaker who is fluent in English, has an American-ish accent, but have trouble pronouncing certain words. After listening to each recording, they were asked to rate how likely they would hire each recording’s voice as their teacher, lawyer, or a doctor. We selected these job fields because teachers, lawyers, and doctors are known to have high-intelligent, high credibility. The ratings were done on an interval scale of 1 (less likely) to 5 (most likely), and the ratings were done only after they listened to each recording.

Results & Analysis

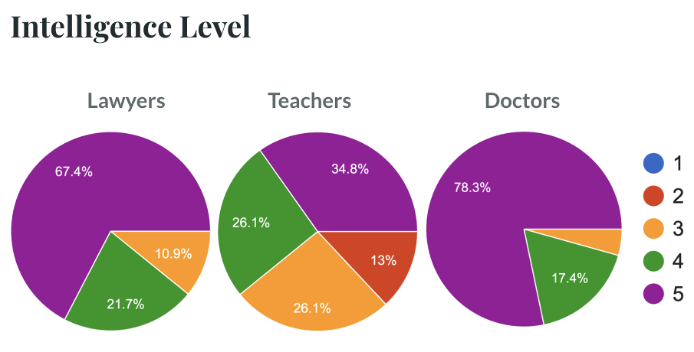

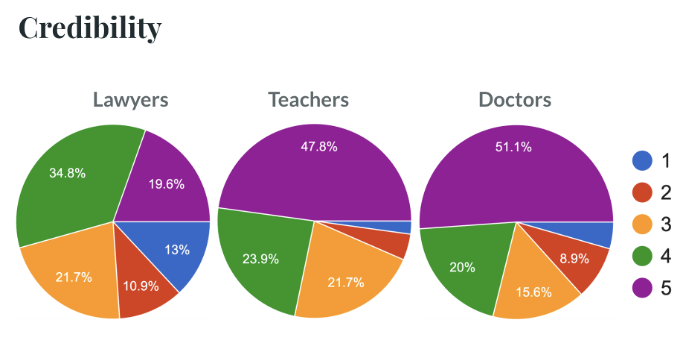

From Table 1 and 2, we can see that most participants agree that the three professions—lawyers, teachers, and doctors— intelligence level and credibility lie between 4 or 5 on the Likert scale, which indicates that they agree the intelligence level and credibility of these professions are relatively high.

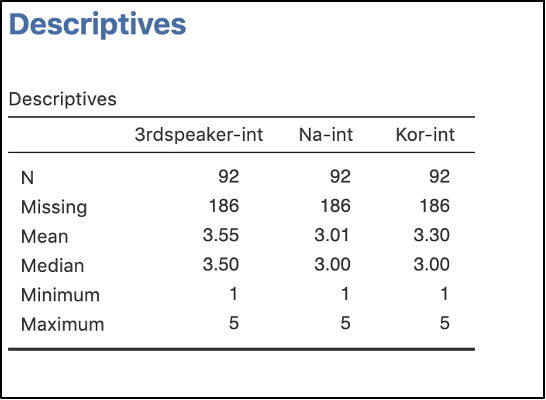

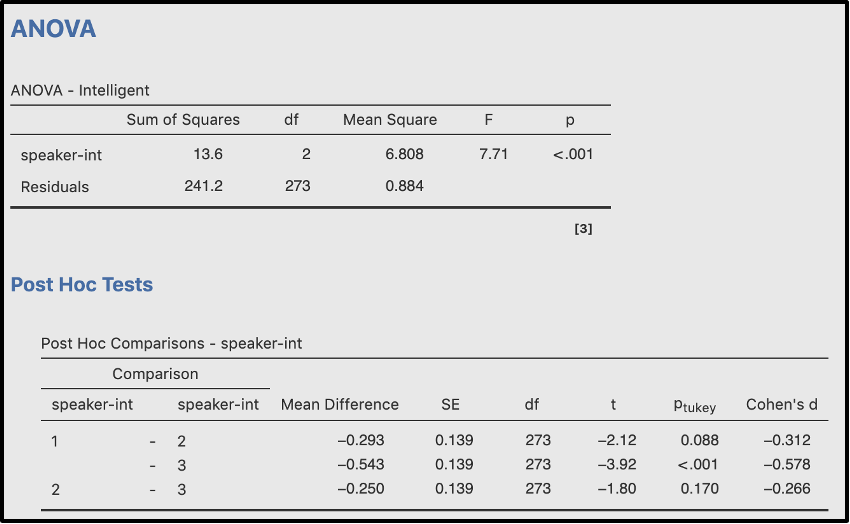

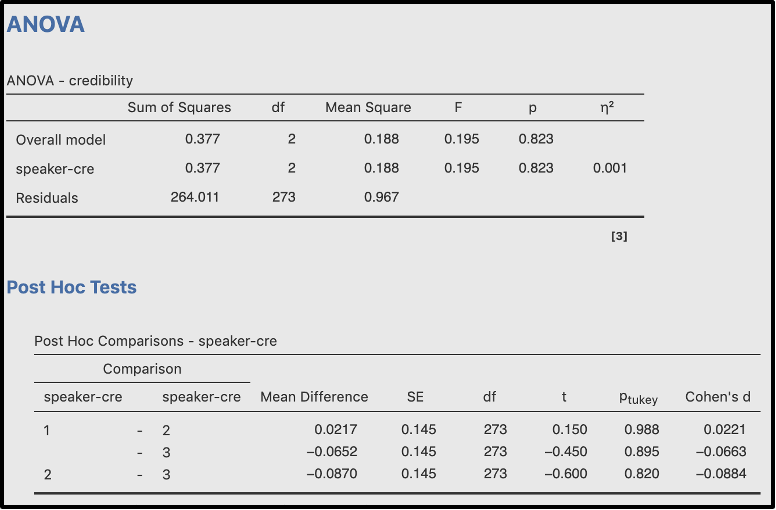

The data were run with two major systems: ANOVA and Post Hoc test. ANOVA gave an idea of whether there is a significant relationship between all three speakers, whereas the Post Hoc test compared each individual relationship between the three speakers. The following tables demonstrated the results of the ANOVA test as well as the Post Hoc test in terms of intelligence level and credibility. Note that speaker 1 represents the native speaker, speaker 2 represents the Korean accented speaker, and speaker 3 indicates the 3rd speaker.

The means of intelligence level of the three speakers are presented in Table 1. The native speaker has a mean of M = 3.01, the Korean accented speaker has a mean of M = 3.30, and the 3rd speaker has a mean of M = 3.55.

According to Table 1, the ANOVA test in terms of intelligence level demonstrated a p-value of less than o.oo1. It is known that a p-value less than 0.05 rejects the null hypothesis and indicates that it is statistically significant. Since we found statistically significant results by computing the ANOVA, we also ran a Post Hoc test to determine where the differences come from. The Post Hoc test suggested the mean differences of intelligence level between a native speaker and a Korean-accented speaker being 0.293; between a native speaker and 3 being 0.543; and between Korean-accented speaker and 3 being 0.250. The largest difference in means occurred between a native speaker and 3rd speaker with a native speaker mean of M=3.01 and a 3rd speaker mean of M=3.55 words. Although we found a significant relationship among the three speakers, the data does not support our hypothesis as we hypothesized that the Korean accented speaker’s intelligence level will be rated as the lowest, but the results suggest that the native speaker is rated as the lowest.

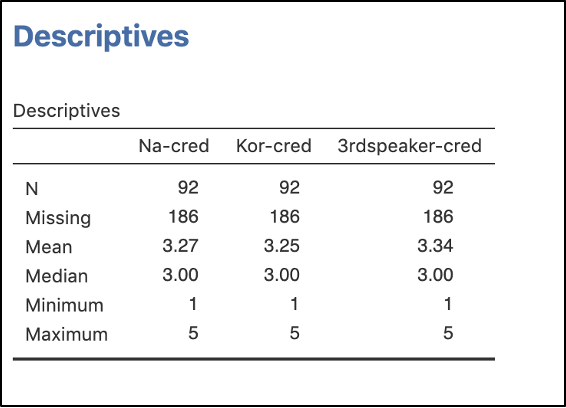

The means of credibility of the three speakers are presented in Table 3. The native speaker has a mean of M = 3.27, the Korean accented speaker has a mean of M = 3.25, and the 3rd speaker has a mean of M = 3.34.

Although in terms of credibility, the Korean accented speaker has the lowest rating compared to others, the ANOVA test in Table 2 demonstrated a p-value of p > o.05, which indicates that there are no significant differences. This result shows that the rate of credibility among the three speakers is similar, and thus reject our hypothesis that the Korean accented speaker will be perceived as less credible.

The results contradict our hypothesis. Our results suggest that Korean accented speakers are not perceived as less favorable in terms of both intelligence level and credibility.

Discussion

This research aimed to investigate how non-English speaking Koreans perceive socially and how others’ perspectives were. The ratings of credibilities and intelligence level were not as expected, and we are assuming that is due to the slower speaking pace that the native speaker recorded in the recording. Moreover, the ratings of Korean ESL speakers were not as expected and disconfirmed our hypothesis, which was that Korean ESL speakers were often treated less credible and less intelligent. However, there was a significant main effect on the intelligence level ratings between the three speakers. The third speaker with an American-ish accent was rated highest among other speakers, suggesting a third variable of speaking pace since the third speaker spoke at a fast speaking speed.

There are some more limitations in the study, such as gender bias—we only used voice recordings of male speakers. So we might want to include female recordings to avoid gender bias. Secondly, there might be a participant bias, meaning participants might assume what our study was about and rate accordingly. We also see some tendencies in the job fields; for instance, teachers were not rated as expected in the pre-rating survey. They were rated not highly enough than our expectation on both credibility and intelligence level. Since the recording was quite long, there might be selective attrition. Participants might feel bored and drop out during the experiment and rate every Likert scale as 3, which is neutral. Lastly, the sample size used was very small. Most participants were UCLA liberal arts students, and most of them were our friends who are also Korean ESL speakers. Since the participants are our friends, they could recognize our voice recordings during the experiment, which could affect the ratings. Moreover, since the sample size was small and limited, the study cannot generalize all Korean ESL students. We hope further research will consider speaking pace for future directions—for example, the relation of speaking speed and one’s perception. Or removing the slow speaking rate and making all the recording speakers talk about the same speaking pace. Moreover, to investigate further, we suggest using a Latin square counterbalanced 2×2 factorial design to see the interaction between gender and accented speech in the perception of credibility and intelligence level. So the first Independent variable would be gender (male, female), and the second Independent variable would be the accent with two levels: accented speech and non-accented speech. Further research would need more diverse participants in age and demographic. And hoping the further study could research other East Asian ESL speakers, not only limited to Korean ESL speakers.

References

English Language Learners in Public Schools. National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf.

FAQ: Why Do Some People Have an Accent? Linguistic Society of America. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/faq-why-do-some-people-have-accent.

Lev-Ari, S., & Keysar, B. (2010, June 25). Why don’t we believe non-native speakers? the influence of accent on credibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103110001459

Lippi-Green, R. (2012). English with an accent: Language, ideology and discrimination in the United States. Routledge.

Rickford, J.R., & King, S. (2016). Language and linguistics on trial: Hearing Rachel Jeantel (and other vernacular speakers) in the courtroom and beyond. Language 92(4), 948-988. Doi: 10.1353/lan.2016.0078.

‘speaking American’: Regions, accents and the subtleties of language. Knowledge@Wharton. (2017, January 18). Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/speaking-american-regions-accents-and-thesubtletis-of-language/.