Serena Gutridge, Ally Shirman, Jennifer Miyaki, Paige Escobar, Paulina Cuevas

Are the variations in sign language attributed to just a flick of the wrist? This study provides an analysis of the relationship between agents’ identities within the Deaf community and their signing style. In the United States, signers use American Sign Language (ASL) and Signed Exact English (SEE) on a continuum. These variants differ on a number of different levels concerning syntax (sentence structure), lexicon (words), and morphology (word parts with meaning). We investigated the relationship between different sociocultural factors (e.g. age, education, family) and a signer’s use of the linguistic features from these two variants (think: different choices of words or signs!) across various conversation topics related to identity. Our results suggest a correlation between using ASL features and the discussion of more personal topics, particularly those related to identity. On the other hand, SEE features were more prominent when discussing more mundane topics (e.g. errands, opinions on cars).

Big D ‘Deaf’ versus little d ‘deaf’

The Deaf (or, deaf) identity is not confined into one category. There are two distinctions often made when referring to the Deaf/deaf identity: big D ‘Deaf’ vs little d ‘deaf’.

Big D ‘Deaf’ refers to the cultural aspect of being Deaf. Those who refer to themselves as “Big D Deaf” tend to have stronger Deaf identities and participate more actively in the Deaf community. Big D Deaf people are also often people who went to Deaf schools or who were raised in Deaf households.

In contrast, “little d deaf” refers specifically to the medical condition of deafness and people who identify themselves in this way typically have a less strong Deaf identity (Lucas, 1989). They are also more often than not, people who are postlingually deaf. Postlingual deafness is deafness that occurs after the acquisition of language, so typically after the age of 6.

One of the most interesting differences between these two is their signing. People who refer to themselves as “Big D Deaf” tend to sign more on the ASL side of the spectrum, while those who refer to themselves as “little d deaf” tend to be more on the SEE side of the spectrum. But what exactly is ASL and SEE, and how are they different?

ASL versus SEE

Like spoken languages, signed language has variations that are identified as somewhat different languages: American Sign Language (ASL) and Signed Exact English (SEE). Most people are aware of the existence of ASL because it is the standard form of sign language in the United States, but SEE is another, more informal style of sign language that is more similar to the typical expectation of how sign language works. It’s important to note that SEE is not a language in itself, but a variety of sign language modeled around English syntax (Power et al.,, 2008). ASL is its own language that has different grammatical structures than English and does not necessarily have exact equivalent signs for English vocabulary. SEE, on the other hand, is a literal translation of English into signs that uses the same linear grammatical structure as English.

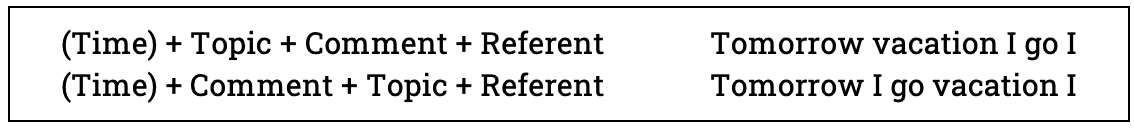

There are two different typical constructions for simple sentences like “I am going on vacation tomorrow” in ASL as you can see in Table 1 below. Additionally, interrogative words (do, who, what, when…) appear at the end of sentences and are often used in rhetorical questions in place of using “because” (I went to the store why? I needed eggs).

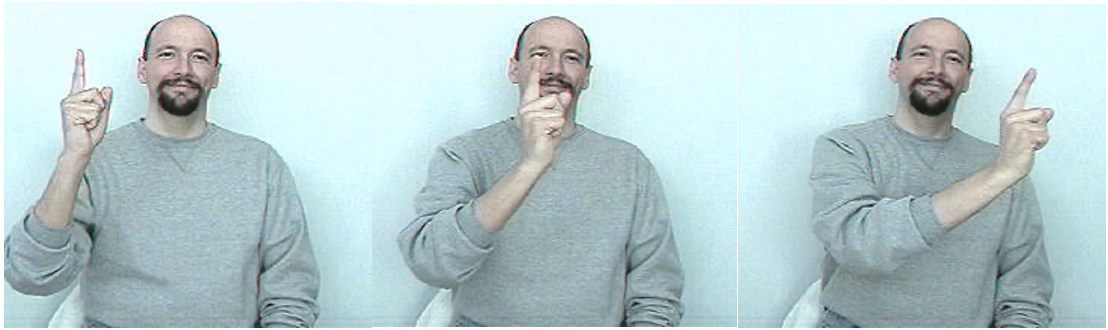

ASL is not a liner language meaning that the signs are not the only elements that are used to communicate meaning. Mouth morphemes are movements made with the mouth that convey information or add grammatical information to signs. Non-manual markers are elements of communication that aren’t hand signs, such as facial expressions, body positions (like a signer’s shoulders shifting to the left or right during signing) and head position. Mouth morphemes and non-manual markers are essential for communicating temporal aspect, distance/length, emotions, distinguishing between different signs, and various adjectives/adverbs (Valli & Lucas, 2000). You can find an example of facial expressions used as non-manual markers in Figure 1 below.

On the other hand, SEE sign follows the English linear word order and uses connectors (and, because), prepositions (e.g. on, in, to, when, during, of), and articles (fingerspelling “the,” “a/an”). Because of the linear order of SEE, mouth morphemes and non-manual markers are unnecessary since the concepts they communicate are expressed with their own signs in the linear word order exactly like in English (Valli & Lucas, 2000). The following video by ASL THAT is a great example of the difference between ASL and SEE.

ASL vs. SEE Comparison | ASL – American Sign Language

ASL typically employs a “show not tell” style of communication meaning that signs often look like what they mean. This non-arbitrary connection between the sign and its meaning is similar to onomatopoeias in spoken language like “boom,” “crash” and “meow.” These iconic signs are crucial for ASL and are exemplified by signs known as iconic classifiers such as the one shown in Figure 2. Classifiers are used to show the events or actions being explained instead of explaining them using other signs in the way that we tell stories in English(Valli & Lucas, 2000) (Vicars). Think of ASL as a picture that shows something and English as the caption that explains that something.

These types of signs are not so necessary for SEE because of literal signs. SEE will often use literal signs as if the signer was literally translating English into signs. So, people will sign “online” as “on line” using the signs for “on” and “line” but will not often use iconic classifiers.

Background

Signing style is a spectrum, meaning that no signer will sign purely ASL or purely SEE and many signers use a pidgin style of sign which combines elements of the two. There are many different aspects of life that contribute to an individual’s signing style and overall Deaf identity, including education and access to Deaf education, family, and social connections to the Deaf community.

Education is a large part of the development of an individual’s Deaf identity – such as if they were mainstreamed or if they went to an oral Deaf school. Being “mainstreamed” refers to a deaf child who goes to a non-deaf school, where an oral Deaf school is a school for the Deaf that emphasizes the use of spoken language. Often oral Deaf schools do not engage in the use of sign language at all, which can greatly influence the signing style of the individual, as well as their identity within the Deaf community (Nikolaraizi, 2006).

In addition, if the person either grew up in a Deaf or signing household can influence not only their signing style but also the development of their Deaf identity. But whether their family utilizes sign language is not the only influence family can play on an individual’s Deaf identity and signing style. Much like how school teachers and peers’ views on deafness can influence an individual, how the person’s family views their deafness can also have the same amount of influence. If people around them have a negative view of deafness then that can cause the individual to also view their own deafness as a negative.

But lastly, if the individual regularly attends Deaf events or has friends who are either Deaf themselves or who can sign can also heavily influence their Deaf identity. With all these factors influencing the development of a person’s signing style and Deaf identity it’s no wonder that not each individual views their deafness the same way. But this raises the question of whether these two factors, signing style and Deaf identity, are interrelated in any way.

The big question

Since ASL is the mainstreamed language of the Deaf community and SEE sign is the less prestigious variety, does the spectrum of sign language used by an individual directly correlate to educational background and/or a sense of identity with the Deaf community?

Methods

To answer this question, five participants were recruited through UCLA’s ASL club (Hands On) and through personal connections of the authors. The ideal participant was someone fluent in sign language, but not limited to someone who exclusively uses only ASL or only SEE. Highlighting the spectrum of SEE to ASL use is important for understanding how usage of the variations correlates with Deaf identity, so a diverse group of participants was key. For reference later on, note that the individual participants are nicknamed as colors (Aqua, Violet, Blue, Cyan, Maroon) for privacy.

Each participant filled out a survey for demographics (age, gender, and if they’re a UCLA student) and background information related to signing. Participants described their hearing capabilities; Other questions asked about language acquisition (when the participant learned to sign), family context (if family members are deaf/Deaf and sign with the participant), language use with others, as well as education history (mainstreamed, Deaf school, tutoring, etc).

Once background information was collected, participants either submitted a recording of themselves or participated in a Zoom meeting answering a variety of questions. Note that three participants answered the prompts alone, while the remaining two participants (Cyan and Maroon) partook in this portion of the study together.

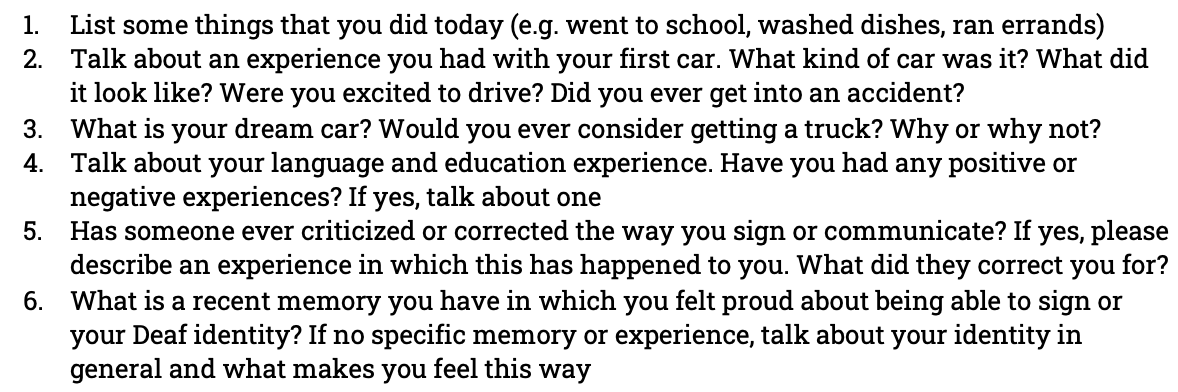

The interviews were conducted to later analyze the participants’ use of SEE and ASL – how much they used each variety and in which contexts. Listed below are the questions asked, in the order they were given to the participants:

- List some things that you did today (e.g. went to school, washed dishes, ran errands)

- Talk about an experience you had with your first car. What kind of car was it? What did it look like? Were you excited to drive? Did you ever get into an accident?

- What is your dream car? Would you ever consider getting a truck? Why or why not?

- Talk about your language and education experience. Have you had any positive or negative experiences? If yes, talk about one

- Has someone ever criticized or corrected the way you sign or communicate? If yes, please describe an experience in which this has happened to you. What did they correct you for?

- What is a recent memory you have in which you felt proud about being able to sign or your Deaf identity? If no specific memory or experience, talk about your identity in general and what makes you feel this way

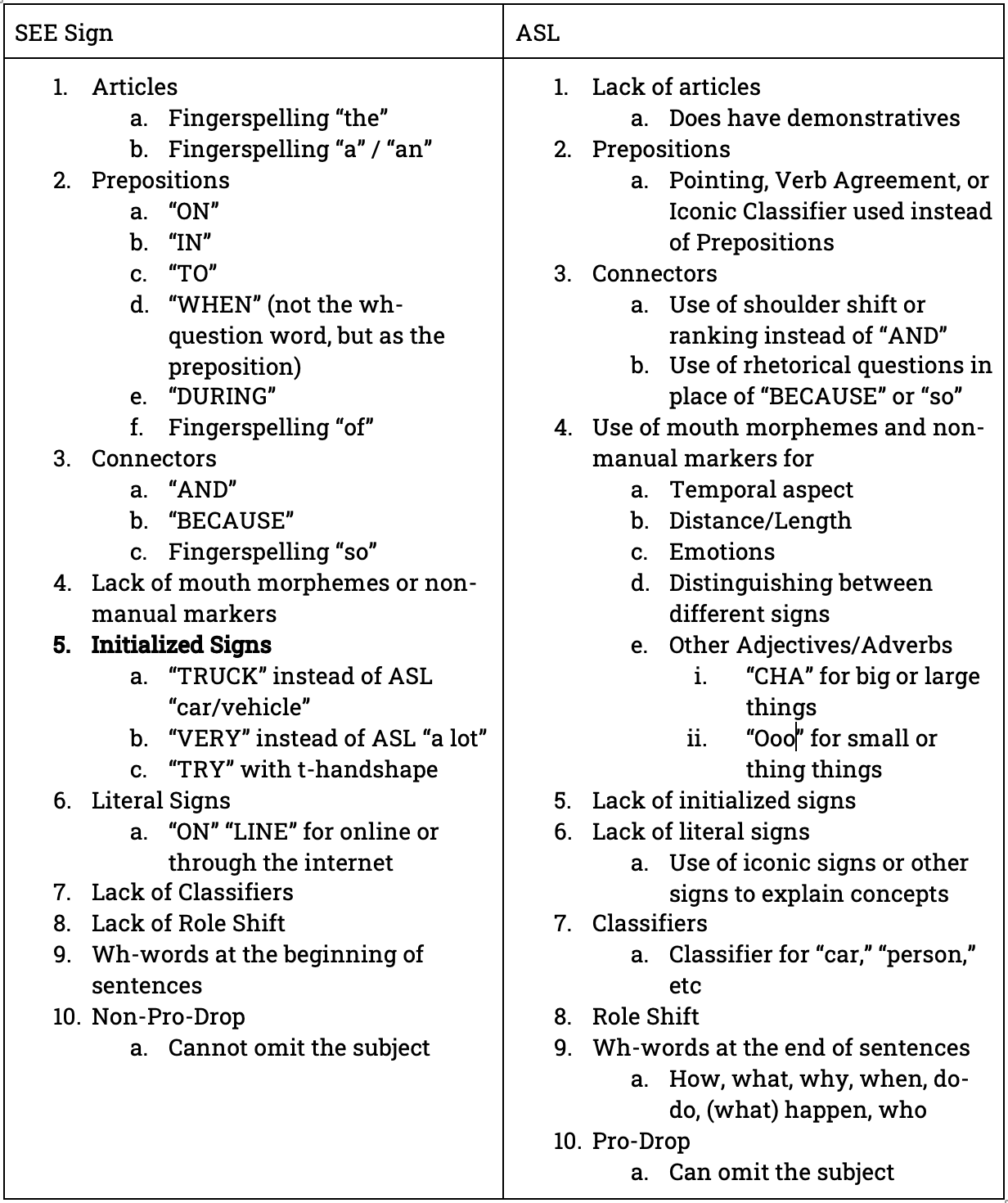

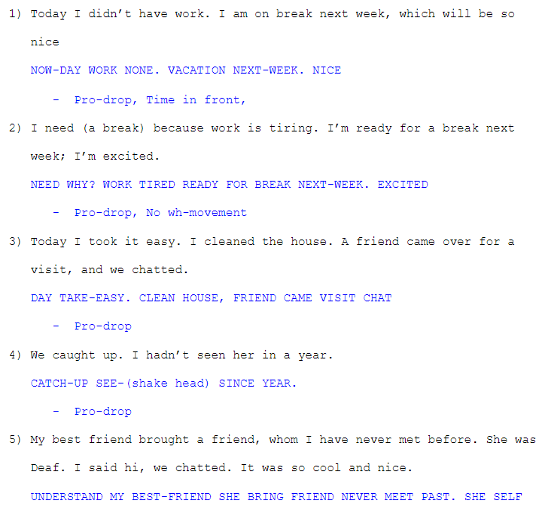

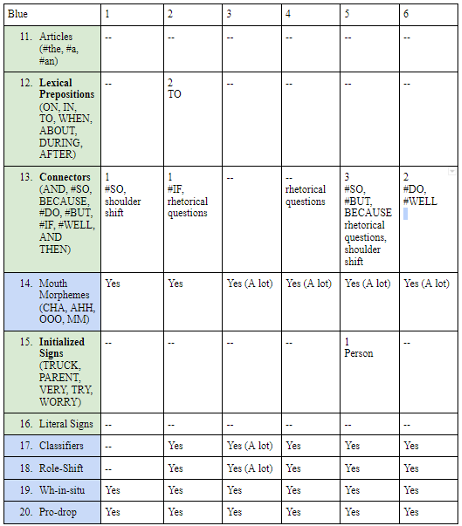

Throughout the interview, general markers of both ASL and SEE were tallied for all participants, shown in Table 2 below. Participants were only communicated with through text to ensure that participants’ varieties weren’t influenced by the type of signing from the experimenters when giving instructions.

The questions were designed to trigger specific ASL or SEE marked signs. For example, Q1 prompted list making, which differs between ASL (finger ranking and shoulder shift) and SEE (using “AND” and absence of ranking and shoulder shift); Q3 asks about trucks to observe if participants would initialize the sign for “car,” (see Figure 3) holding both hands in fists and pretending to be steering, with the letter “T” to denote “truck,” or use “car/vehicle” for both cars and trucks as done in ASL.

Data Collection

Over 80 minutes of footage of the participants signing their responses to the questions was reviewed, transcribed, and coded. See Figure 4 for an excerpt of a transcript we did.

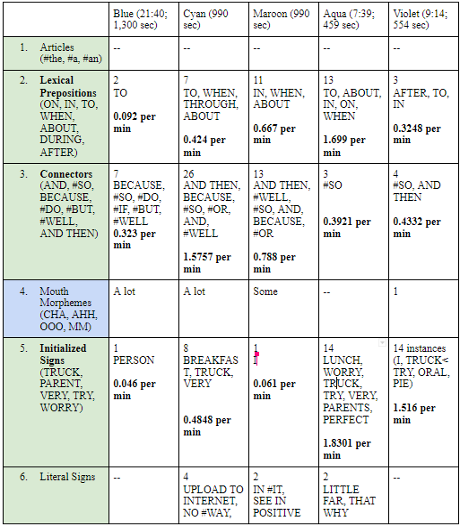

Their answers were interpreted by the researcher fluent in ASL and then translated into English. After interpreting the conversations, each feature was made note of in our charts. The charts were organized by each participant’s answers and then condensed into a larger (“mother”) chart with data from all participants. See Figure 5a for a chart done for an individual participant, and Figure 5b for an excerpt of the “mother chart.” SEE features were counted and tallied, while the frequency of ASL features were qualitatively described, since the SEE features being looked for were specific lexical items and thus, easier to count.

Analysis

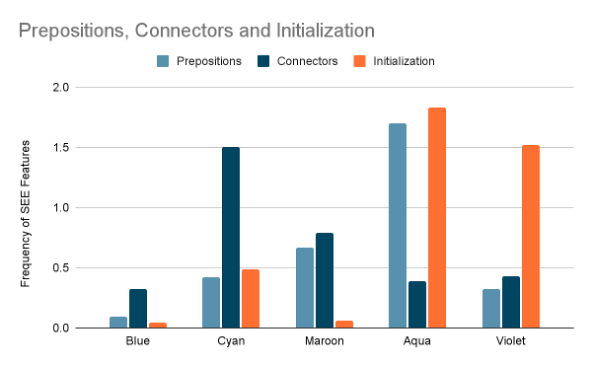

When sorted based on different categories of SEE features (e.g. prepositions vs. connectors vs. initializations), signers each had their own individual frequency of each linguistic category. Some signers utilized numerous initialized signs, but had low frequencies for connectors and prepositions. See Violet in Figure 6. Others had low frequencies for prepositions and initializations, but a high frequency for connectors. See Cyan in Figure 6. It is important to note that high instances of a certain feature were often repetition of the same sign and can be attributed to signing style, which would explain why the data is exaggerated for certain features in some signers. For instance, Cyan had high levels of ASL features (e.g. role shift, mouth morphemes) and low levels of SEE prepositions and initializations. However, she had a high use and repetition of the same connectors (e.g. fingerspelled “so”).

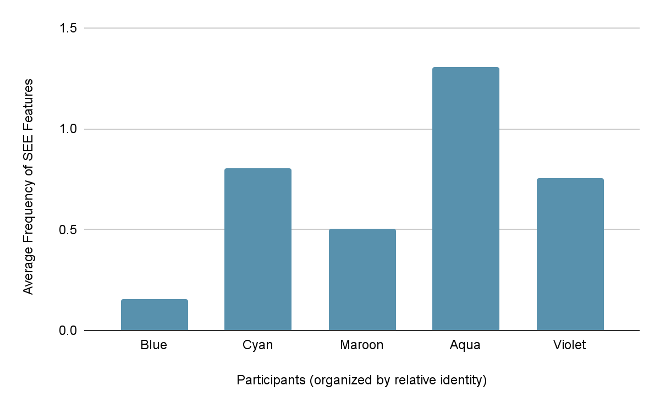

In addition, signers’ use of SEE features correlated with key factors related to Deaf identity, such as educational background, age, and family. In Figure 6 and Figure 7, participants are organized from left to right based on a subjective organization of these key factors.

Through this, we are able to make note of significant differences in the signers. Although both Blue and Violet identify with the Deaf community, educational factors contribute to their Deaf identity. In fact, Violet initialized signs 32.956 (3,295.6%) times more per minute than Blue. Violet, our oldest participant, attended an oral deaf school in her youth and was prohibited from signing in the classroom and encouraged to only speak and read lips. Blue, out of all our signers has the highest level of education in regard to ASL, having attended Gallaudet University for a master’s degree, where ASL and English are both the language of instruction. Gallaudet University is the only liberal arts Deaf university in the world. The CODA (Child of Deaf Adult) of the group, Aqua, has the lowest level of formal ASL education, but is a native signer in which their parents are both Deaf. See Figure 7 for an average frequency of SEE features for each participant. Keep in mind that Cyan’s frequency of SEE features may not be a completely accurate representation of where she falls on the ASL-SEE sign continuum, since she had a high frequency of connectors due to repetition of the same lexical items. In addition, Cyan had the second highest frequency of other ASL features, such as role-shift and mouth morphemes.

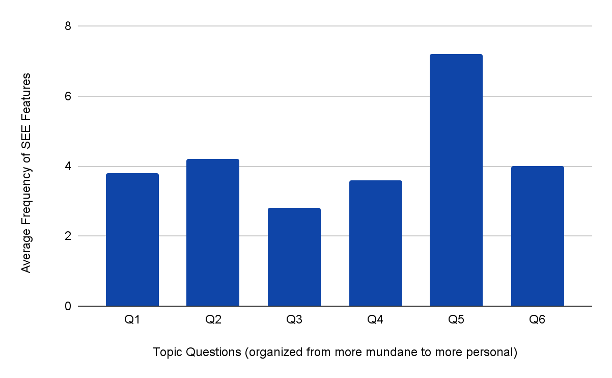

Not only was there a correlation between frequency of SEE features and relative Deaf identity, but the type of conversation topic was also a factor that influenced the frequency. See Figure 5 for average frequency across conversation topics. More mundane topics (e.g. Questions 1/2/3) had a higher degree of SEE features with the exception of Question 5. Question 5 triggered an unexpected stark increase in the frequency of SEE features as participants detailed past experiences of being criticized for their signing. This high frequency may be due to participants slipping into the variant that they were criticized for (in this case, signing more SEE over ASL). For some participants (e.g. Aqua and Violet), Question 3 did not trigger enough of a response due to lack of interest in the topic (dream car), therefore rendering a lower frequency of SEE features than expected. Considering ASL features in conjunction to the data presented in Figure 8, we witness that the topics that were more personal (Questions 4/5/6) have a lower frequency of SEE with respect to the more mundane topics, with exception to question 5 as aforementioned.

Additionally, note that the two signers, who leaned more on the SEE side of the continuum, tended to correct themselves while signing. A signer would begin an initialized sign then quickly amend their sign to the ASL variety. This may have happened because they were aware of their SEE signing feature as less prestigious to ASL and made the correction as a form of meta-linguistic awareness.

Limitations & Future Research

Exemplified data does not take into consideration ASL features which would show more personal topics have less SEE features in comparison. Since the data is unable to reflect the instances of ASL features because they are not as easily countable as the lexical features of SEE, there is a low visual significance with respect to topic and sign preference.

Discussion

Though this research focuses on a very small sample size, this research is an example of how language can index identity and whether a speaker or signer chooses to use one linguistic feature over another can range depending on social context, the topic at hand, and the interlocutor. Our results suggest that certain topics can trigger different responses in which signers may shift or choose a particular identity or set of linguistic features from their linguistic repertoires they would like to showcase in that given situation. More mundane topics may trigger different linguistic features than more personal ones, especially when a particular variety has less prestige over another in a given community (in this case, the Deaf and signing community). The correlation between signing style and Deaf identity found in this study aligns with the more researched theory that language variety can index an agent’s identity and is replicable in many other sociolinguistic areas.

References

Gallaudet University – What you do here changes the world! (2021, November 15). Gallaudet University. https://www.gallaudet.edu/

Lucas, C. (1989), The Sociolinguistics of the Deaf Community. Academic Press, Inc.

Lucas, C., Valli, C., & Bayley, R. (2001). Sociolinguistic Variation in American Sign Language (1st ed.). Gallaudet University Press.

Nikolaraizi, M. (2006). The role of educational experiences in the development of deaf identity. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11(4), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enl003

Power, D., Hyde, M., & Leigh, G. (2008). Learning English From Signed English: An Impossible Task? American Annals of the Deaf, 153(1), 37–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26234486

Stremlau, T. (2003). Language Policy, Culture, and Disability: ASL and English Rhetoric Review, 2003, Vol 22, No. 2, 184-190.

Valli, C., & Lucas, C. (2000). Linguistics of American Sign Language Text, 3rd Edition: An Introduction (3rd ed.). Gallaudet University Press.

Vicars, W. (n.d.). ASL University. Retrieved from https://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/lessons/lessons.htm