Joseph Anderson, Jason Luna, Ethan Perkins, Helia Woo

An increasing and alarming number of cishet men performing purportedly homosexual behavior can be seen on social media. Current research suggests there is also a decrease in homophobia and homohysteria. Our study aims to explore how changes in support of homosexuality have also changed the language of homosocial relationships. In this context, homohysteria is defined as the heterosexual’s fear of being thought gay when performing gender atypical behaviors. Homophobia is defined as attitudes and behaviors that demonstrate intolerance of sexual acts, identities, morality, and the rights of homosexuals. To test our hypothesis that cisgender heterosexual (cishet) men will use language commonly indexed and correlated with the language of women and homosexual men when interacting in homosocial conversations with close friends, we analyzed 40 TikTok videos which featured cishet men in homosocial environments, and recorded five 30–40-minute conversations that took place either in person or online via Zoom and Discord. We found that cishet men, when in a comfortable setting with other cishet men, seem to use linguistic patterns that are typically indexed with cishet women and gay men. These results suggest that our hypothesis is true, despite our limited data.

Intro

Like many of our peers, our nights are filled with casually staring at the screen of our phones, scrolling for hours through an endless number of TikTok videos. Yet, after watching some cute puppy videos, hilarious scripted comedy, and some fantastic lip-syncs, we noticed a common theme of the videos in between: TikToks of two allegedly straight men, going in for a kiss, only for the camera to cut out right before their lips would touch. The most puzzling part: the #nohomo and #homiesexual tags underneath.

In recent years, contemporary pop culture seems to have an obsession with homosexuality — just without the part that requires anyone involved to actually identify as non-heterosexual. Like the TikToks mentioned above, various other social platforms, such as YouTube and Instagram, seem to be becoming home to male influencers engaging in “gay” behaviors with other men, despite neither party involved actually identifying as part of the LGBTQ+ community. From the iconic “Two bros sitting in a hot tub” Vine (Figure 1, re-uploaded to YouTube here), to recent online discourse about men keeping their socks on during sex acts with other men to keep it “no homo” (Figure 2), performative homosexuality seems to always be played for comedic effect. However, with the emergence of the phenomenon of men “playing gay” online in conjunction with the introduction of words like “homiesexual,” we were curious as to the ways in which language played a role in homosocial relationships, or the relationships between cisgender heterosexual males.

Background

Current literature identifies three phenomena — homophobia, homohysteria, and queerbaiting — as core to the emergence of the identity of the homiesexual, which, according to the NYT involves “straight men who go beyond bromance and display nonsexual signs of physical affection.”

- Homophobia is an umbrella term for all attitudes and behaviors that demonstrate intolerance of sexual acts, identities, morality, and the rights of homosexuals (McCormack & Anderson, 2014).

- Homohysteria involves the heterosexual male fear of being thought gay when performing gender atypical behaviors (McCormack, 2011).

- Queerbaiting and gaybait are the deliberate insertion of homoerotic subtext in order to court a queer following without actualizing the subtext (Brennan, 2018).

Primarily, research on the subject centers on how increases in the acceptance of homosexuality and decreases in homophobia and homohysteria have led to new interpretations of what it means to be a cishet male (McCormack & Anderson, 2010; McCormack, 2011). However, this interpretation of the construction of the cishet male identity focuses on the concept of “bromance” and conversational dyads rather than group relationships among men and lacks discussion of specific linguistic properties (Robinson et al, 2018). Still though, other literature discusses the stereotype of male conversation being emotionally closed and unaffectionate (Sargent, 2013, Roberts et al, 2017).

Our research aims to fill the gap between the identification of these cultural phenomena and the analysis of specific linguistic forms and explore how changes in support of homosexuality have also changed homosocial relationships. There is a dearth of research on the speech of straight men because the speech of straight men is commonly perceived as the norm to be compared against when investigating minority speech. Cameron (2014) comments that this might be because the foundations of the monolith that is straight speech include a massive, diverse group of individuals, meaning that it would be hard to identify straight men as a singular community of practice. In fact, heterosexuality could be seen as an unmarked sexual identity because it is society’s default and no one has to “come out” as straight.

Additionally, in the same speech, Cameron states that this lack of research may be due to the fact that advocating for more research on heterosexuality could be seen as hostile to the larger purpose of the study of language as activism meant to advocate for minority communities.

However, to understand the gender performance and gender identities and what place that has in the social landscape, especially for minorities, it is essential that we study all groups, including heterosexual men, in order to ascertain whether something is actually specific or actual indexical of certain identities.

There has also been some study of the concept of “sounding gay” and the idea that non-heterosexual men, specifically homosexual men, often index the speech of heterosexual men in order to seem “straight passing” (Gaudio, 1994). Though, again, not much work has been done to understand how straight individuals might index non-straight language.

So, after recognizing the phenomenon of cishet men possibly becoming more comfortable with non-traditional performances of masculinity, sexuality, and gender, we wanted to uncover if these beliefs might also be influencing the language of cishet men.

Hypothesis

We hypothesize that cisgender, heterosexual (cishet) men will use language commonly indexed and correlated with the language of women and homosexual men when interacting in homosocial conversations with close friends.

This language may include:

- compliments on attractiveness

- calling one another pet names

- raising pitch and using falsetto

- hedging

- pausing

Methods

In order to shed light on this phenomenon, our research entailed two components: (1) a content analysis from popular social media clips and (2) conversational analysis of interactions among friend groups involving at least two cishet men.

1. Content Analysis:

We analyzed 40 TikTok videos from compilation videos on YouTube with titles such as “straight guys being gay guys” or from the TikTok tags “#nohomo” or #homiesexual”. This analysis was performed to reveal preliminary insights into what behaviors we might be searching for during real-life conversations. Primarily, we analyzed conversation sequencing, diction, and body language.

2. Conversational Analysis:

Subsequently, we recorded five 30 – 40 minute conversations either online (through Discord or Zoom) or in-person in groups of 3 to 5 people including the recorder. Participants were told that at some point during the conversation, the researcher would begin recording. Sometimes the participants would be informed when the recording would start and other times they would not.

Results and Analysis

TikTok Data

Observations of the TikToks included the following:

- escalation, competition, one-upping (e.g., “gay chicken”)

- mirroring couple-like behavior (e.g., using pet names, intimate physical behavior, a man engaging in activities with another man that he’s only done with his girlfriend)

- signals of discomfort after initiating gay behavior

- comedic effect created through heteronormativity

- comedic effect created through homohysteria

- comments about each other’s bodies

- dropping the gay act in the presence of a third party

- use of a third party (girlfriend or other audience) to signal that gayness is not serious

- hypersexualization of gayness (e.g., horniness or making sexual advances being the foremost marker of gayness)

- making advances at the expense of the other man’s comfort

- gayness being ingrained in heterosexual male friendships

- use of the phrase “no homo” to ward off homosexuality

Findings from the TikToks can be grouped into three categories: homohysteria and heteronormativity, gender roles and misconceptions about homosexuality, and the spectrum, or lack thereof, of male intimacy.

Homohysteria and heteronormativity

Typically, comedy involves surprise—a subversion of expectations. TikTok creators relied on the concept of heteronormativity, the assumption that everyone is straight, as well as the normalization of homohysteria to create a comedic effect. Cishet men also played up homohysteria for humor by acting gay or hinting at one another’s gayness, while simultaneously expressing discomfort.

Heteronormativity also manifested itself more subtly in other ways: men filmed gay TikToks in front of their girlfriends, reinforcing the norm of heterosexual hegemony by using the idea of gay couples as a joke (Figure 3). When calling other men by pet names, men occasionally used names typically associated with women, such as “baby girl,” once again reinforcing the norm that a couple consists of one man and one woman (Figure 4).

Gender roles and misconceptions of homosexuality

Other TikToks revealed the gender norms prevalent between male relationships, as well as a clear misinterpretation of homosexuality by cishet men. Cishet men, in acting gay, often joked that their girlfriends wouldn’t “find out” ignoring morality (of cheating on a signficant other) in favor of producing a humorous effect (Figure 3). They also hypersexualized gayness; many interactions involved words such as “horny,” “sexy,” and words relating to the sexual organs, and behaviors such as moaning or eating a sausage. This hypersexualization often blurred the line of comfort for those on the receiving end of a straight man’s gay advances—many men were confused and/or uncomfortable, as evidenced by their facial expressions or verbal reactions, even though they did not resist (Figure 5).

These behaviors signal misconceptions, often harmful, about male homosexuality—that homosexuality is inherently more sexual or less ethical than heterosexuality. However, because of the comedic nature of such behaviors, it is also implied that many of these men are aware of their misconceptions and deliberately play on them to heighten the humorous effect. They also signal an adherence to gender norms, as we will discuss further in the conclusion.

Extremes on the spectrum of male intimacy

Cishet men showed a tendency to either avoid any intimacy, or show it at an extreme level. In particular, men frequently said “no homo” to immediately eliminate any assumptions of legitimate homosexuality. On the other end of the spectrum, they often played “gay chicken” (in which they continued to act more and more gay until one person finally cracked) or tried to one-up each other in acts of gayness. In some situations, men did not necessarily try to compete with the other, but refused to show weakness by stepping away from their advances (Figure 6). These competition-centered interactions are likely attempts in asserting dominance and subordinating one another.

Discord Calls / In-Person Recordings Data

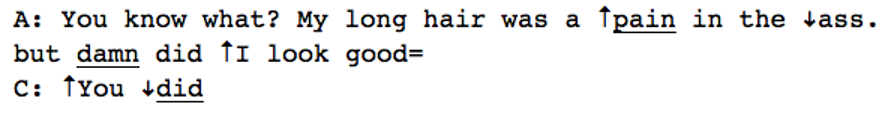

For the online Discord recordings, as well as the in-person recording, interactions were able to be placed in a few categories. Each interaction is numbered based on the order in which we are presenting them, rather than the order in which they were recorded. Firstly, many interactions could be considered compliments, both innocent (not inherently sexual) and explicit (sexual in nature). Figures 7.1 and 7.2 below show examples of innocent compliments, in which participants A and C compliment each other’s hair.

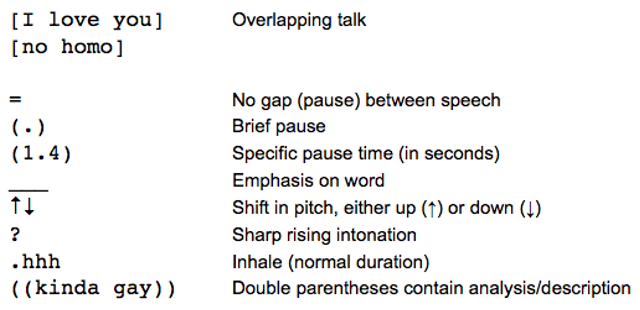

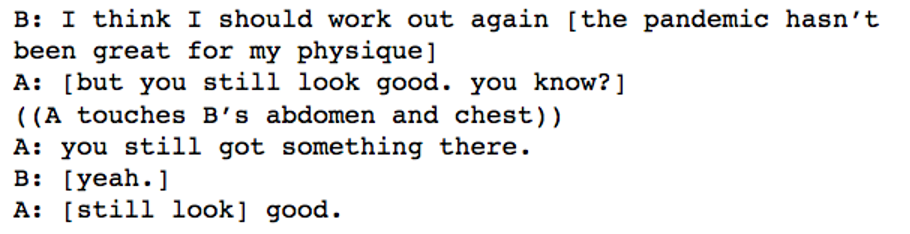

Conversation Analysis Transcription Key

Innocent Compliments

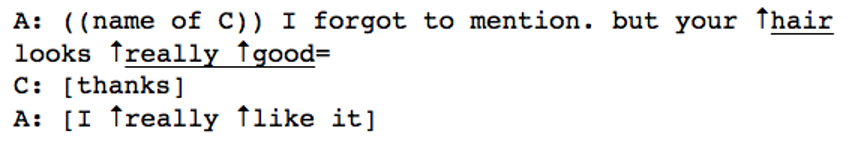

Physical Touching

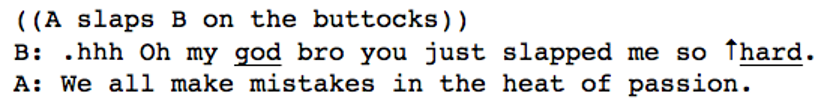

In Figure 8.1 below, we can see another example of a compliment; however, A’s compliment of B’s physical appearance also includes physical touching. Here, as is shown in the ((double parentheses)), A touches B’s abdomen and chest while complimenting him. There were other instances of physical touching, such as the interaction in Figure 8.2, in which A slapped B’s buttocks.

Explicit Compliments

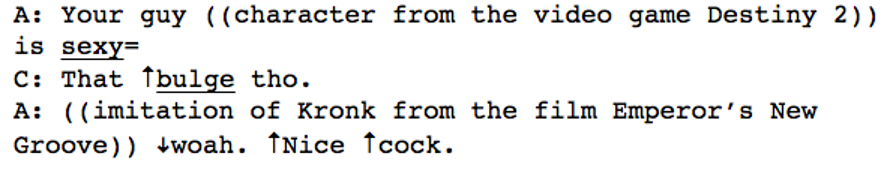

Other compliments given from one participant to another were explicitly sexual, such as the below interaction in Figure 9.

In Figure 9, A and C were referring to participant B’s male character from the video game Destiny 2, with A referencing a specific meme in the last line.

Pet Names

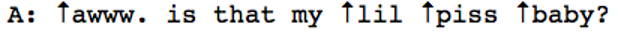

A pet name was only recorded in one interaction, seen below in Figure 10, in which A referred to B as his “lil piss baby.”

Other Flirtatious Interactions

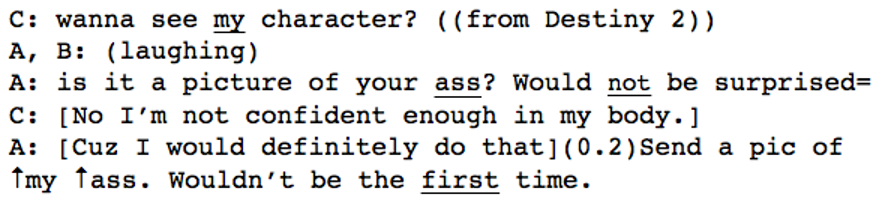

Additional flirtatious behavior was recorded, including the interaction in Figure 11. For some context, A and B were comparing video game characters from Destiny 2, when C offered to show his character, jokingly, since he did not play the game.

Intonation

When it came to intonation changes (as illustrated in the figures by the up or down arrows), the pitch of the participants’ voices seemed to raise when mentioning a body part in a sexual manner. This is seen in Figure 9, when C mentioned “bulge,” as well as in Figure 11, when A mentioned “my ass.” Additionally, intonation rose when A and C were complementing each other in Figures 7.1 and 7.2. A’s intonation also significantly rose when calling B by a pet name, as shown in Figure 10.

Hedging

Finally, we looked at hedging, or filler words that mitigate or downplay the severity or seriousness of a statement. The most common hedges found in our data were “you know,” “I mean,” and “I don’t know, but.” An example of the hedge “you know” can be seen in Figure 8.1, after A complimented C. Additional hedges included “might” and “really,” as shown below in Figure 12, where A hedged his opinion on the TV show “The Office.”

Discussions and Conclusions

Our data and analysis support our hypothesis. Cisgender and heterosexual men, in interactions with other cisgender and heterosexual men, tend to use linguistic patterns indexed with gay men or straight women; these patterns include higher intonation and hedging. In addition, cishet men use flirtatious speech in these homosocial environments, such as compliments, pet names, and sexually-charged comments, many of which were observed with higher intonation. An important note to make, however, is that despite similarities in speech patterns, many of the behaviors cishet men exhibit in homosocial settings are not indexed with gay men or straight women. For instance, the hypersexualized actions cishet men engage with seem to be exclusive to cishet men.

The main conclusion we can draw from our findings is that despite decreasing levels of homophobia and shifting views on non-traditional forms of masculinity, sexuality, and gender, heteronormativity and gender norms remain prevalent. As explained in the analysis section, cishet men’s “gay act” relies on heteronormativity to create humor in the first place. Gender norms can explain the ubiquity of confusing or unwanted advances towards other men: it is likely that men expect other men to show less “fragility” and therefore “take it like a man,” as the saying goes. The convention of male dominance also may explain the competitive aspect of acting gay. Furthermore, the dissonance between the two extremes of male interaction (overly intimate or not intimate at all) implies once more the pervasiveness of gender roles and stereotypes, as men are expected to be less affectionate and more emotionally closed-off. Thus, although cishet men know how to index gay or non-cishet male identities, as indicated by their shifted speech patterns, they are still heavily influenced by larger outside forces that suggest our views have yet to fully break away from the heterosexual and patriarchal norms.

Additional Reading / Viewing

Everyone Is Gay on TikTok (New York Times)

The Evolution Of Queerbaiting: From Queercoding to Queercatching (YouTube – Rowan Ellis)

Project Presentation (Anderson, Luna, Perkins, Woo)

References

Brennan, Joseph. “Introduction: Queerbaiting.” The Journal of Fandom Studies 6.2 (2018): 105-113.

Cameron, D. (2014). Straight talking: the sociolinguistics of heterosexuality. Langage et société, (2), 75-93.

Gaudio, R. P. (1994). Sounding gay: Pitch properties in the speech of gay and straight men. American speech, 69(1), 30-57.

McCormack, M. (2011) Mapping the Terrain of Homosexually-Themed Language, Journal of Homosexuality, 58:5, 664-679, DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2011.563665

McCormack, M. (2011). The declining significance of homohysteria for male students in three sixth forms in the south of England. British Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 337-353.

McCormack, M., & Anderson, E. (2014). The influence of declining homophobia on men’s gender in the United States: An argument for the study of homohysteria. Sex Roles, 71(3), 109-120.

McCormack, M., & Anderson, E. (2010) The re-production of homosexually-themed discourse in educationally-based organised sport, Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12:8, 913-927, DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2010.511271

Roberts, S., Anderson, E., & Magrath, R. (2017), Continuity, change and complexity inthe performance of masculinity among elite young footballers in England. The British Journal of Sociology, 68: 336-357. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12237

Robinson, S., Anderson, E., & White, A. (2018). The bromance: Undergraduate male friendships and the expansion of contemporary homosocial boundaries. Sex Roles, 78(1), 94-106.

Sargent, D. (2013). American masculinity and homosocial behavior in the bromance era.