Elisha Daria, Julia Jacoby, Jocelyn Martinez

Since their inception in 1999, emojis have become essential to how we communicate. Utilizing the iconographetic communication model devised by Christina Margrit Siever (2019), our group wanted to examine and compare how people use emojis within a public sphere, such as Instagram or Twitter, versus a private one, such as SMS. We hypothesized that emojis used in a more public sphere would have a much more structured approach with primarily decorative or aesthetic purposes as a means of marketing a distinct online persona; for more private spheres, we hypothesized that emoji usage would be a lot more broad and relaxed, with more frequent usage overall and less standard forms or unspoken usage rules. Drawing our data from 48 high-school to college-aged individuals from Generation Z, we used a mixed methods approach in measuring intra-user variation from platform to platform. In doing so, we analyzed emoji frequency and usage patterns, and were able to see distinct differences in the ways in which our demographic used emojis to communicate. Our findings indicated that there was indeed an intra-user difference in emoji usage in public versus private spheres, but the ways in which these differences manifested came down to personal preference from user to user.

An Introduction to Our Study

In an increasingly digital world where technological literacy has become a necessary skill, emojis have become an invaluable aspect of digital communication in the twenty-first century. This study seeks to understand the ways in which we use emojis in the context of iconographetic communication in our day-to-day lives (Siever, 2019). From one-on-one conversations with a close friend via text, to an open-ended public conversation initiated by a single Tweet, our team wanted to measure and observe intra-user variation in public versus private spheres. In doing so, we hoped to see the motivations, methods, and reasoning behind the use—or omission—of specific kinds of emojis in daily digital interactions. These practices are especially prevalent in individuals born from the years of 1995 to 2009, known as Generation Z. These individuals have grown up in the age of the smartphone, and play a crucial role in the dynamic nature of online trends. In analyzing high-school to college-aged Gen Z social media users, we hoped to get a look into the linguistic influences of the demographic at the forefront of digital branding.

A particularly interesting element of more public platforms such as Instagram and Twitter is the way in which the user is forced to find a balance between achieving mass appeal and maintaining some semblance of individuality and authentic self-expression. This results in versatile social media users who are skilled at accommodation to a wide audience while also creating and presenting a distinct online persona. By comparing and contrasting the patterns in emoji frequency and usage between platforms, we wanted to see how a public or private audience ultimately impacted the speaker’s choices. As the first study of its kind, we hoped to gain insight into the unspoken common practices that govern digital communication.

Understanding Iconographetic Communication & Gen Z

Utilizing the term coined by Christina Margrit Siever, we focused our study on instances of iconographetic communication (2019) among high school to college-aged social media users of Gen Z; in doing so, we were hoping to find trends in the digital communication practices of this demographic. On average, each member of Generation Z is exposed to thirteen hours of media a day, producing individuals who are “highly creative, constantly adaptive, and have a highly marketable digital mindset” (Vitalar, 2019). In tracing these users’ patterns of usage across SMS, Instagram, and Twitter, we were expecting to see some form of intra-speaker variation, with emojis used as sociolinguistic markers (Van Herk, 2018, p. 54, 120). This means that each individual would use emojis differently from platform to platform, subtly tailoring their specific iconographetic communication methods to fit their public or private sphere. Examples would include the use of certain prestige forms or targeted rhetoric, as well as the use of emojis for stylistics and aesthetics to create and promote a specific brand. Studies have shown that social media influencers use emojis as a means of adding appeal, enhancing and amplifying persuasive content, and encapsulating emotional appeals through marketing rhetoric (Ge & Gretzel, 2018). Tactics such as these are key for maintaining user engagement, which is an integral part of the social media experience for regular users as well.

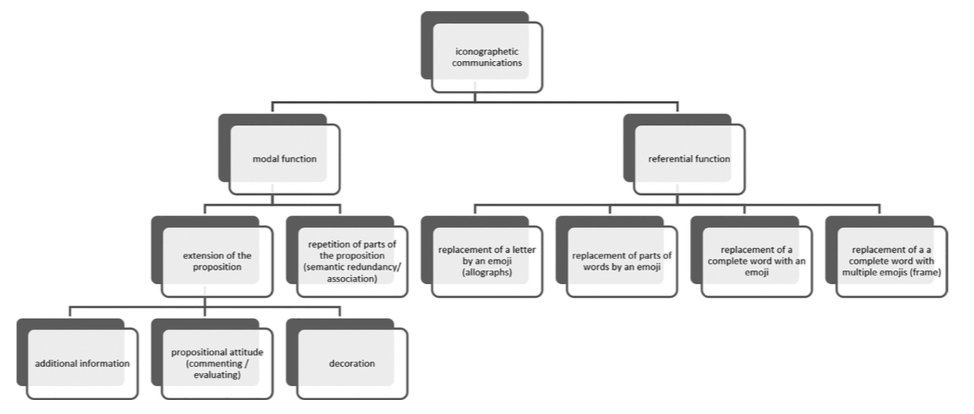

Siever’s iconographetic communication model was crucial to this study because it gave us a framework for viewing the ways in which emojis are used in communication. With “icono” derived from the Greek for “image” and “graphic” derived from the Greek for “writing,” iconographetic is a catch-all term that combines pictoral and typed characters and gives context to the unique linguistic function of emojis as typed images that convey sentiments worth a thousand words. Figure 1 shows Siever’s model in its entirety, with iconographetic communication branching into its modal and referential functions. The modal function describes an emoji’s ability to complement and modify written messages, while the referential function is used when an emoji replaces words or parts of words as an extension of the linguistic proposition (Siever, 2019, p. 130, 137). When coming up with our digital survey, we tailored our questions to fit either the modal or referential function, and also used this model in analyzing actual texts, Instagram posts, and Tweets submitted by one of our participants.

How We Conducted Our Study

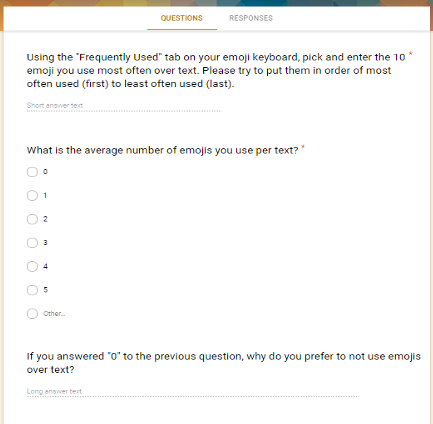

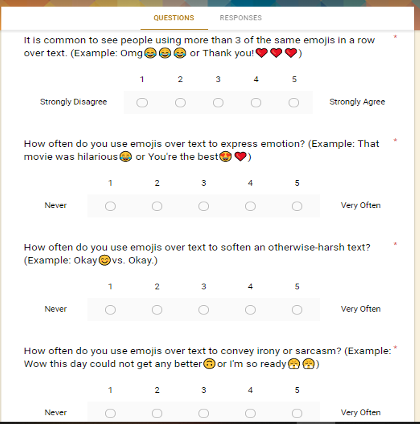

To conduct this research, our team used a mixed methods approach by collecting and analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data. We began our data collection by sending out a Google survey to forty-eight participants between the ages of fourteen and twenty-four. The survey consisted of three sets of questions regarding personal emoji usage within text messaging, Instagram, and Twitter. All participants were required to answer the text messaging portion first, then could choose to take either the Instagram or Twitter section—or both—depending on their personal usage habits. As seen on the right in Figure 2, our quantitative data was drawn from Likert scale questions on a scale from 1 to 5 (Likert, 1932, p.17), allowing us to create visualizations such as graphs and charts that helped us recognize emoji usage patterns. For qualitative data, we included short answer questions, as seen in the “short answer text” options of Figure 2, allowing for individualized feedback. We then analyzed the information we received from these qualitative responses to pick out the themes and patterns we found amongst our participants. Utilizing Siever’s iconographetic communication model (2019), we analyzed both types of data with the objective of finding the differences in the way people use emojis to communicate meaning across different digital platforms.

What We Found

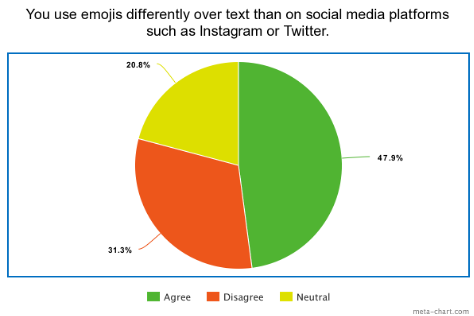

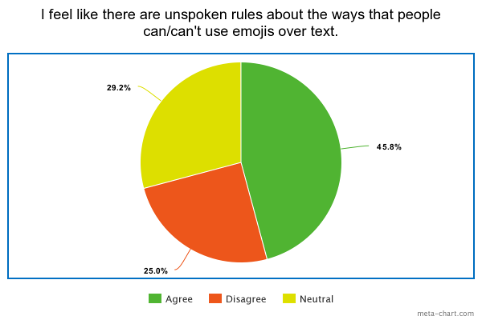

Taking a look at the results of the survey, the data showed that the majority of participants agreed that they use emojis differently in when texting versus social media (Figure 3). One person said, “On social media I try to keep it more trim and professional, to an extent, whereas with texting I’m more casual, so I use more emojis.” The majority also agreed that there were some unspoken rules about how emojis should be used within text messaging. When asked what some of those rules might be, another person said “Using emojis to convey tone of voice or mood of the conversation (e.g., hey 👋 vs. hey 😏).” Further proving our hypothesis specific to text messaging habits, we saw that a total of 81.3% of participants use 1 or more emojis per text, 79.5% per Instagram post, and 70% per tweet on average. This proves our hypothesis that private platforms have more frequent usage than public ones.

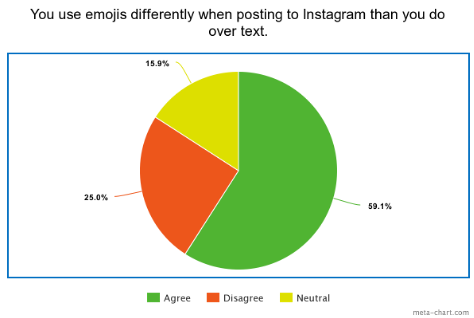

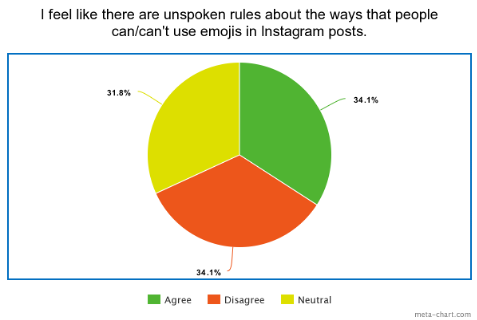

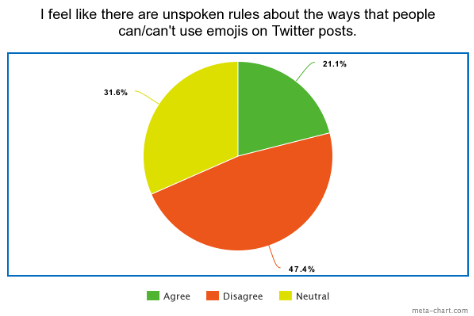

As for the social media portion, users of Instagram and Twitter agreed once again that their emoji use differed compared to texting (Figures 4 and 5). Some of the Instagram respondents said: “I use emojis mainly for aesthetic purposes for Instagram” and “You’re more conscious of how everyone else will perceive what you post instead of just one person.” About one third of respondents agreed on the existence of rules for using emojis in Instagram captions. Responses about unspoken rules varied and were dependent on each individual’s personal preference and self-expression.

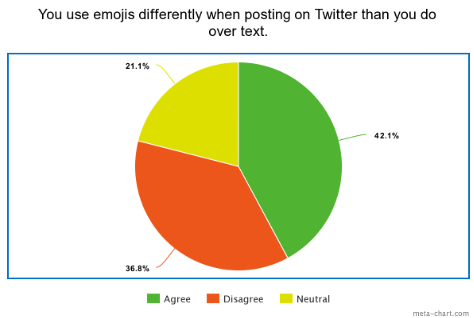

Similarly, many Twitter participants claimed to use emojis differently because within this platform, more people would be seeing their Tweets. However, almost half of the respondents did not believe there are unspoken rules for emoji usage within this platform (Figure 5). This may be due to the lack of respondents to the Twitter portion of the survey, which could have skewed our data. Nonetheless, this supports our idea that there is more structure and hidden rules to emoji usages within private communication than there is within public communication. Our hypothesis about aesthetic and decorative usage in public spheres was also proven correct. As seen in Figure 6, only 16.7% of participants said that they use decorative emojis in their texts, while Instagram and Twitter users use decorative emojis nearly twice as much (40.9% and 31.6%, respectively).

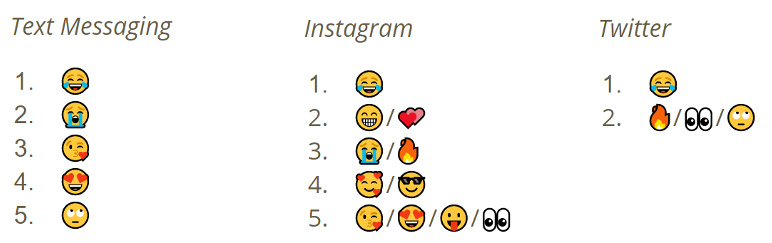

Figure 6. Survey responses regarding aesthetic/decorative use of emojis.To see which emojis are most common, we asked participants to list up to 10 of their most frequently used emojis. The laughing/crying emoji held the #1 spot across all three, but the rest of the rankings varied (Figure 7). This leads us to believe that the laughing/crying emoji expresses universal sentiments that are socially acceptable across all platforms, both public and private. Interestingly, the sideways glancing eyes emoji and fire emoji appeared in both Instagram and Twitter data, but not in the text messaging data. This implies the existence of standard forms for public platforms to express emotions specific to Twitter/Instagram culture.

This might have something to do with meme culture specifically, as these memes are often used to express sarcasm or a certain aesthetic online.

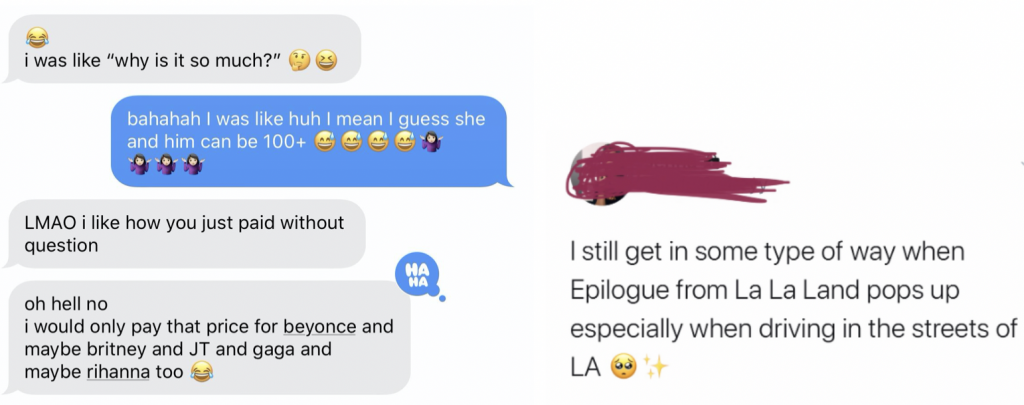

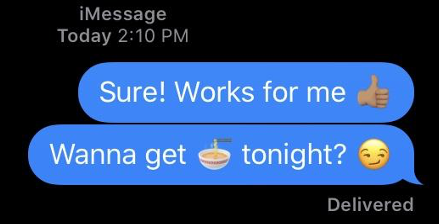

Lastly, we asked one participant who uses Twitter, Instagram, and text to provide us with screenshots of her personal emoji usage. We took these and compared each example of emoji use with the functions on Siever’s model (Figure 1). On the left of Figure 8, the emojis convey emotion to complement the content of her text. This is likely propositional attitude under modal function because the emojis add comment and evaluation to her statement. Also in Figure 8, ✨ is used to add aesthetic/decoration to text (modal function). Figure 9 shows an example of the much less common referential function, where an emoji takes the place of an entire part. Here, 🍜 replaces the word “ramen” in the sentence.

Overall

The results from our survey support our hypothesis partially. The findings demonstrate that there is a difference in emoji usage between public and private forms of communication, as we had originally predicted. However, we found that there are more unspoken rules and structure with the usage of emojis when they are being used through private communication such as text messaging. We believe this is because the personal nature of text messages makes the user feel pressured to put more thought into the messages their emojis might send. Interestingly, our participants also indicated that they are more comfortable using emojis through text messages since they are not out for the whole world to see; this explains the higher frequency of emoji usage through text. Therefore, it appears that users are more comfortable using more emojis over text once they make sure they are using them in a way that ensures their message will be construed correctly. In contrast, on more public platforms, users choose to use more general emojis for descriptive or aesthetic purposes, with less frequent usage overall.

References

Bell, A. (1984). Language style as audience design. Language in Society, 13(2), 145–204.

Ge, J., & Gretzel, U. (2018). Emoji rhetoric: a social media influencer perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 34(15-16), 1272–1295.

Herk, G. V. (2018). What is sociolinguistics? Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 5–55.

Siever, C. M. (2019). ‘Iconographetic Communication’ in Digital Media. Emoticons, Kaomoji, and Emoji, 127–147.

Vitelar, A. (2019). Like Me: Generation Z and the Use of Social Media for Personal Branding. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 7(2), 257–268. doi: 10.25019/MDKE/7.2.07