Tiffany Dang, Brianna Lombardo, Carlos Salvador Vasquez, Denisa Tudorache, Yuyin Yang

The present article focused on linguistic markers that are adopted by the Women Loving Women (WLW) population when identifying potential members of the WLW community. More specifically, this study focused on the strategies used by members of the WLW community for identifying fellow WLW with the intentions of pursuing a romantic or sexual relationship. Through analyzing popular YouTube videos featuring strategies on flirting with WLW, our first study captured the common beliefs regarding the need to take an extra step, and the possible methods on identifying WLW before taking any romantic or sexual advances. Followed-up by semi-structured interviews in study two with UCLA students who self-identify as WLW, we were able to examine the accuracy of the tips offered by the YouTube videos. This allowed for further investigation on the existence of specific linguistic markers adopted by WLW when flirting. We found that both popular YouTube videos and participants both discussed the need for WLW to take an extra step before they can comfortably pursue another woman and tend to make a conscious effort to not be too direct.

Introduction and Background

While there have been past studies done on examining the speech of gay men, particularly the California vowel shift among gay men (Podesva, 2011), and one that revealed a concept of gay-dar, the belief that gay men possess an ability to pick out each other in a crowd (Shelp, 2003), little research has been done on uncovering linguistic patterns within the Women Loving Women population (WLW). A member of the WLW community is loosely defined as anyone who identifies as a woman and differs from the mainstream preferences in terms of their sexual practice and identity (Eliason & Morgan, 1998). Due to being seen as deviant from the mainstream practices, they may feel the need to take different approaches when making romantic pursuits in order to establish a mutual understanding of their interest in women when talking to another individual. As WLW may often struggle with compulsory heterosexuality, the fear of being perceived as predatory, as well as the potential dangers that come with revealing their sexuality, we aimed to investigate whether there were any linguistic markers adopted among the members of the community to aid in implicitly seeking each other out. This study explores the ways WLW work around the potential barriers they face when pursuing romantic interests and when revealing their identity in hopes of gaining insight on ways to improve the inclusivity of a general community. We hypothesized that WLW would adopt practices where they refer to certain WLW-group-specific terminologies or features before making romantic or sexual advances towards another woman.

Methods

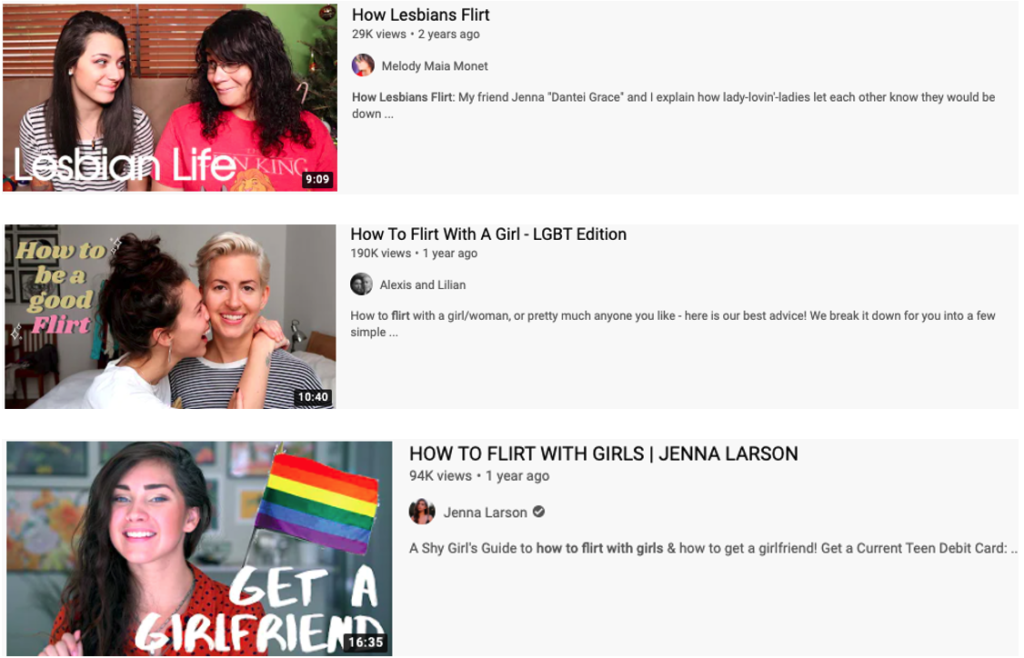

Study 1 collected people’s lay knowledge on identifying WLW by looking at popular YouTube videos that featured strategies on how to initiate romantic/sexual advances with a WLW. We found three relatively popular videos created by members of the WLW community who also covered a large realm of dating advice and made a list of those that were related to indexing sexual identity. In addition, we watched two videos that featured heterosexual dating advice and made note of the advice given to men to romantically or sexually pursue other women. By comparing the two lists of notes, we were able to identify potential strategies that are WLW group-specific.

Study 2 consisted of two semi-structured interviews that took place and were recorded through Zoom. We interviewed a total three members of the WLW community, with two of them being in a committed relationship. They were primarily asked to describe and draw from their past experiences. The interviews were guided by six open-ended questions (see Appendix A) with the interviewer following up with questions when necessary. Our questions focused on the WLW’s description of their experiences in establishing mutual interest in women using non-direct measures. Participants were recruited using snow-ball sampling and all answers were kept anonymous. After the interviews, we listened to the audio recordings and made notes of the different ways WLW chose to index their sexual identity as well as the cues they used to determine the sexual identity of their romantic interest.

Study 1 Results

In Study 1, we were able to uncover several recurring themes. One point made consistently across multiple videos was that the WLW always felt the need to immediately make their sexuality known once they realized they had feelings for the other party.

Reasons for this were that they did not want to confuse the other party into thinking that they just wanted a female friend, and they also did not want the other party to assume that the speaker is straight and think differently of them. WLW worry about giving ambiguous signals if they were to not reveal their sexual identity soon enough, which leads to the subtle incorporations of various cues in conversations, such as mentioning the pride parade, to demonstrate their sexual identity.

They also made mentions of lurking through the other party’s social media for signs pertaining to possible membership of the WLW community to know whether it would be appropriate for them to make romantic advances. WLW also tend to be cautious in making advances as they adopt a “flirting by not flirting” technique. This allows them to slowly determine if the other party has reciprocated romantic feelings without being too overbearing and only continue to proceed if there is a positive response.

WLW flirting: Video 1 Video 2 Video 3

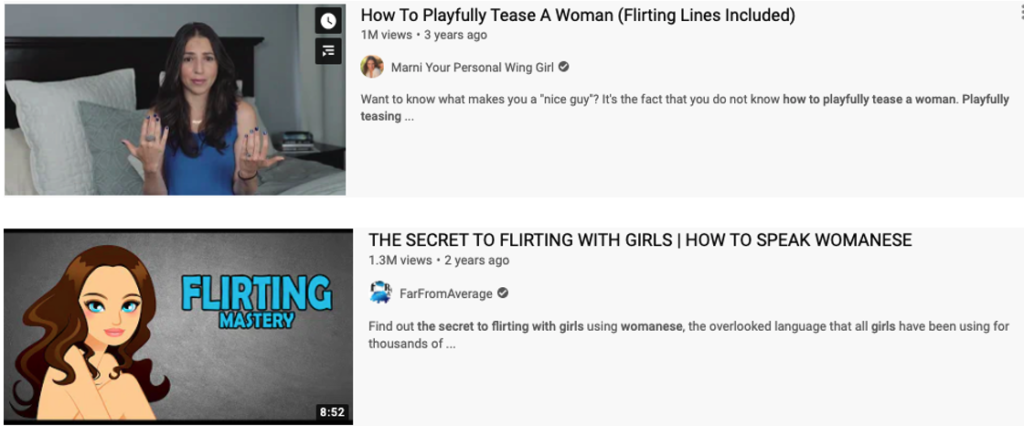

In contrast, when we explored flirting advice geared towards men to pursue women, there was no mention for men to index their sexual identity to women before flirting or at any stage of the courting process. The videos generally focused on advising men to be indirect to increase excitement in women and how to appear playful and masculine.

Heterosexual Flirting: Video 1 Video 2

Although there was some overlap in advice given to women to pursue other women and given to men to pursue women, such as being subtle and indirect, the reasoning behind it was different, and a clear difference was the need for WLW to drop hints about their sexual identity. Because there tends to be less confusion in intentions when a male approaches a female, neither party is advised to hint at their own sexual identity nor advised on how to determine the other party’s sexual identity. In contrast, a common theme across videos geared towards WLW is to use references to hint at their own gayness or try to determine whether the other party is gay before advancing.

Study 2 Results

Interview 1

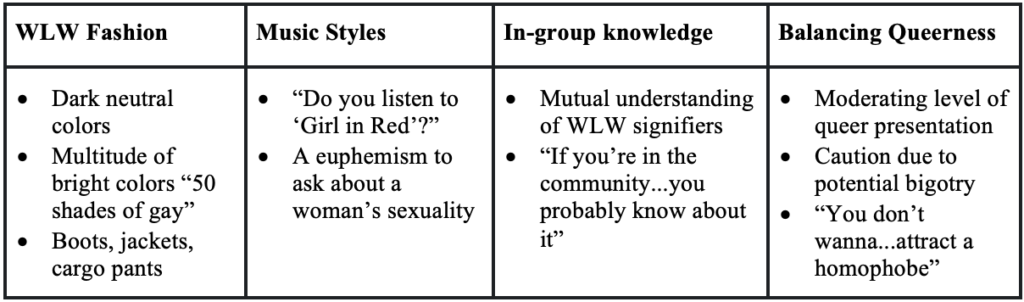

A summary of common themes that arose in Interview 1 are presented in Table 1 below along with some illustrative examples given by the interviewee.

Interview 2

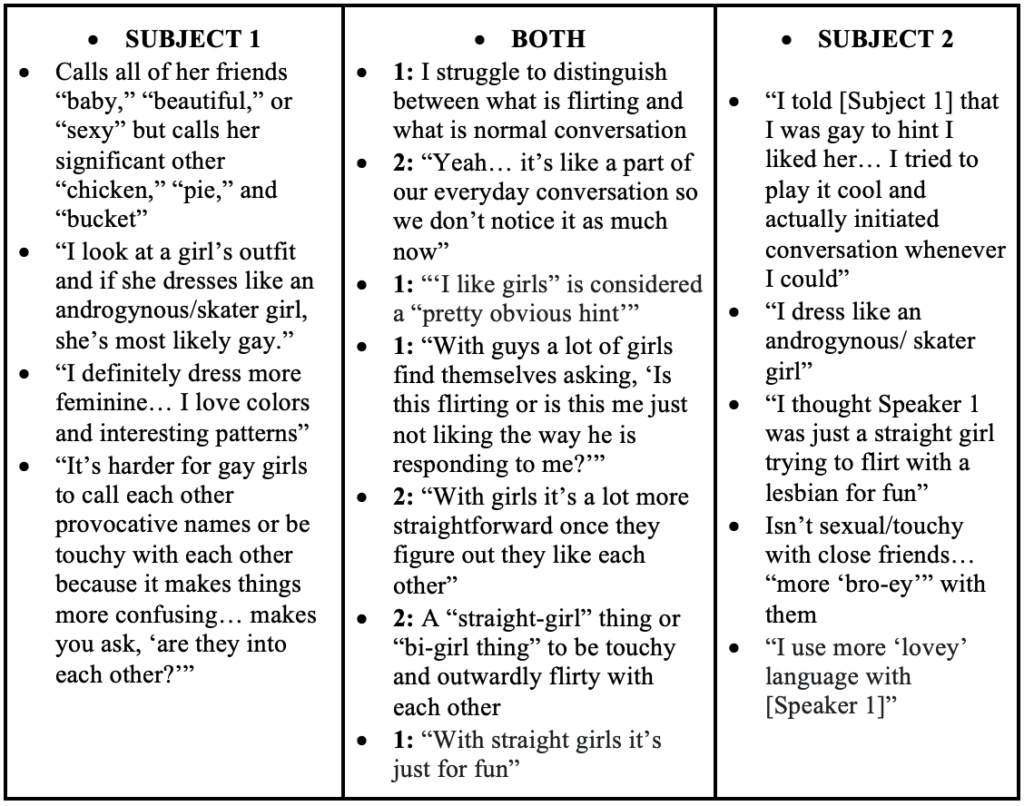

To illustrate the results derived from Interview 2, Table 2 consists of the most important statements made by both Subject 1 and Subject 2 in the conversation. It is important to note that Subject 1 and Subject 2 have been in a WLW relationship for over a year. When answering the interviewer’s questions, they both reflected on when they first met and how this has changed or remained consistent. The middle column consists of what they answered similarly.

Study 2 Analysis

From our interviews we gathered that the majority of strategies available for Women-Loving Women to identify and flirt with other WLW are mostly non-linguistic in nature. In both interviews, WLW referred to style of dress as a primary identifier for fellow WLW. These and other aspects of popular WLW culture were also drawn upon during the flirting itself, which leads us to one overtly linguistic flirting strategy we found was used by WLW– compliments. Compliments between WLW referenced nonverbal yet mutually understood markers of WLW identity, so they were used to confirm sexuality and communicate an attempt to flirt, in addition to their function as simple compliments. Importantly, compliments between WLW and platonic ones between heterosexual women were said to differ solely in their content and not their form. We conclude that this arises from a need or desire for WLW to flirt “under the radar” to avoid the very real danger of homophobia and bigoted comments.

We also noted the potential for confusion and ambiguous interpretations of these, arguably necessary, nonverbal flirting methods. Subject 1 even described a trend among WLW to pull back on “standard” physical or verbal affection (at least among other WLW) as a way to avoid creating confusion since more open displays of platonic affection are expected among groups of women. This may contribute to a societal perception of WLW as being “colder” or “more masculine.” Future studies might investigate whether or not this is true among a larger sample size.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our ultimate takeaway from these interviews was a strong indication that, motivated by a possible fear of negative attention, members of WLW groups feel the need to be covert in romantic contexts. As a result of this covertness, we noticed a trend of relying on nonverbal cues (like clothing choice) more than an awareness of individuals phonetically or lexically indexing their “gayness.”

Even in situations where an individual might directly state “I like girls,” the implication of “I’m romantically interested in you” often remains covert. This gives the other individual a choice as to whether or not an interaction is romantic in nature, but can end up causing some confusion. Thus arises the stereotype that WLW do not flirt. In many cases, their advances can easily be interpreted as platonic interaction among women in a society where affection among women is more normalized than among men, and where revealing your sexuality to the wrong person can have negative repercussions.

Further Reading Recommendations: Although we did not cover this information in our study, there have been numerous studies done on the language WLW may use that distinguish their patterns from heterosexual women. Robin Lakoff in Language and A Woman’s Place (1975), defines stereotypical “women’s language features (WL)” as those associated with “heterosexual women’s performance of femininity.” She contrasts this with the existence of typical “men’s language features (ML),” thus creating a binary of “women’s speech v men’s speech.” It would be interesting to use this and analyze whether women in the WLW community use either one or both of the language features, and whether this could be a distinguishing feature.

References

Eliason, M.J., Morgan, K.S. Lesbians Define Themselves: Diversity in Lesbian Identification. International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies 3, 47–63 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026204208243

Lakoff, Robin (1975). Language and A Woman’s Place. Language in Society, Vol. 2, No. 1, 45-80.

Podesva, R. J. (2011). The California vowel shift and gay identity. American speech, 86(1), 32-51.

Rich, A. (1980). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs: Journal of women in culture and society, 5(4), 631-660.

Rieger, G., Linsenmeier, J. A., Gygax, L., Garcia, S., & Bailey, J. M. (2010). Dissecting “gaydar”: Accuracy and the role of masculinity–femininity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(1), 124-140.

Shelp, S. G. (2003). Gaydar: Gaydar. Journal of Homosexuality, 44(1), 1-14.