Kevin Kim, Kota Tsukamoto, Guorang Zhang, Cindy Zheng

For our experiment, we analyzed Twitch streamers playing Valorant. Twitch, or Twitch.TV, is an online streaming platform popular among gamers. Valorant is a popular first-person shooter (FPS) game created by Riot Games in 2020. Valorant, as of 2021, has an estimated 12 million players, peaking at 15 million in July (Dexerto 2021). The game has a diverse range of players in various regions of the world. Contrary to other FPS games that are very heavily male-dominated, Riot Games has made an effort to increase the number of women in Valorant, resulting in 30-40% of Valorant players being women (VentureBeat 2021). Furthermore, Riot Games has even implemented an all females league as well as pro esports teams such as Cloud9 (known as C9 White) who recruited women for their Valorant teams earlier this year (PC Gamer 2021).

The experiment examined both male and female streamers to compare their vocabulary choices- while the study can incorporate more genders than just male and female, due to the demographic of streamers being mostly male or female, as well as time constraints, we only focused on those two genders.

One particular feature that we analyzed was the amount of provocative language that is done by streamers. The usage of swearing from male or female streamers was recorded in particular situations such as dying, insulting, and having disagreements with another player. We were aware of language most commonly used by gamers such as frags, ace, bait, boosted, clutch, flank, etc that could be more commonly used by one gender than the other (Çakır 2021).

Streamers in our research

This experiment revolved around three male streamers and three female streamers. The three male streamers who were analyzed were: AverageJonas, itsRyanHiga, and Ethos and the three female streamers are Kyedae, Ploo, Tiffae. These six streamers were chosen due to their popularity/recognition, skills, and various personalities.

The male streamers are around 30 years old, and the females are around 20. They are mostly all of white or East Asian descent and are English speakers. To be more specific, AverageJonas is a 32-year-old Norwegian English-speaking streamer, itsRyanHiga is a 31-year-old Japanese American English-speaking streamer, and Ethos is of unknown age and is an Asian American English speaking streamer. Kyedae is a 19-year-old Japanese Canadian English-speaking streamer, Ploo is a 22-year-old Asian American English-speaking streamer, and Tiffae is a 27-year-old Taiwanese English-speaking streamer.

What we already know

Based on gender stereotypes, men are perceived to be louder, more aggressive, and curse and insult more, and also since gaming is seen as a “male-dominant” space, we also thought gaming terms would be more male-gendered as well. Because of that, we decided to analyze vocabulary reactions to certain game events by gender.

We also analyzed the vocabulary differences by comparing streamers in an all-male team and a mixed-gender team. Previous research states that men in an all-male friend group played into male stereotypes in their group interactions more than those who had their girlfriend or female friend in their groups (Cameron 1997). In our experiment, we thought that these previous findings could suggest that female streamers may also feel pressure to conform to their male teammates and speak in a more stereotypically male manner, so that was an aspect we decided to look at.

We decided to analyze streamer and fan interactions between genders. Previous research stated that women communicate to build relationships, so we thought we would see that when observing how streamers interact with their viewer’s donations (Van Herk, 2012).

Methods

For the experiment, we watched six streamers for key vocabulary words in their speech and their chat interactions. The streamer’s vocabulary choices were analyzed when they reacted to these three events: donations from fans, winning a game, and losing a game. The reactions to those events were grouped by event and gender- for example, one group would be “Vocabulary in reaction to winning a game from a male streamer.” Then the groups would be compared across the same event and against opposite genders. An example comparison would be comparing reactions to winning by male streamers against responses to winning by female streamers. We watched each streamer stream for an average of 2 to 3 hours in total.

While we were watching the stream, we noted down some vocabulary and phrases used by the streamer. Then we sorted phrases between each scenario and compared the differences. After we sorted the words and phrases, we looked at the difference between streamers and gender. We also decided to analyze our overall results of vocabulary choice based on the gender of the streamer’s teammates.

Thesis

We found a clearer divide in the vocabulary when we compared streamers that played with all-male team and streamers that played in a mixed-gender team. Through our results, we can conclude that while there were differences in a streamer’s vocabulary due to the streamer’s gender, the main differences relied more on the gender of their teammates. Streamers with all-male teammates used more gaming-specific terms, insults, and cursed more. But as for the streamer’s own gender, we found that females were more likely to negatively refer to themselves in the face of a negative event, while males would blame the game and enemy team. We also found that females were more likely to initiate and maintain friendly interactions with their viewers and team.

Results / Analysis

Win reactions based on streamer’s own gender

To start off, we compared the vocabulary that females used when they won a game versus the vocabulary used by males when they won a game.

Female wins

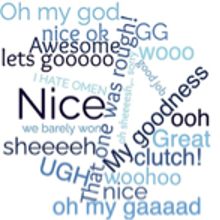

As you can see from the word cloud generated from the data across the three female streamers, we identified that female streamers didn’t use any swear words in the situation of a win. Female streamers tended to comment on the win as the group’s achievement, using phrases that begin with the subject “we”. Two out of the three streamers used different variations of the phrase “oh my god” which is commonly associated with the regional marker of valley girls.  Male wins

Male wins

Looking at the result of the male streamers, we saw that male streamers would swear after a win. One of the male streamers, Ryan Higa used the Sh-word after a win. Overall, when commenting on a win, the male streamers tend to phrase the comment as talking about the game and not how well they played as a group(we).

Through these word clouds, we can see that there’s gendered language – the females kept their female gender identity through speech reminiscent of valley girls, despite being in a male-dominated space, and males, true to our hypothesis, used more crude language.

Loss reactions based on streamer’s own gender

Next, we analyzed the reactions of losses by females and by males.

Female loss

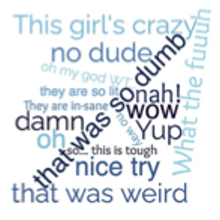

The word cloud on the right shows the utterances of the female streamers when facing the scenario of a loss. Unlike the result from utterances after wins, we saw swear words. The F-word was used in the phrase “oh my f**king god”. Another commonality noticed between the female streamers is that they tend to address the loss of the team as their responsibility, using the subject “I” when commenting on the loss, for example, “I messed up” or “I can’t win a game”. Female streamers also used encouraging phrases such as “that was a very nice try” to show support towards teammates.

Male loss

Male loss

The male players also used swear words after a loss, for example, the F-word was used in the phrases. In general, they form their phrases without criticizing the loss as their responsibility or their team’s responsibility. Instead, they use phrases that begin with “that”, “they” or “this girl” to address the game or the other team/team member.

The main difference between female reactions to losses and male reactions was not what we expected- we saw both genders swear (but males to a greater degree). The biggest difference was actually the target of negative or aggressive language. The females tended to blame themselves for the loss and put themselves as the target of any negative descriptors or words. Males would blame the game or the enemy team. We also saw that females, to further put the blame solely on themselves, would congratulate their teammates.

Donations / subscriptions interactions based on streamer’s own gender

We then looked at reactions from females and males to donations and subscriptions by their fans. We mainly looked at the manner in which the streamers interacted with their fans, and we found that all-male streamers used the same phrase for all their donations and subscriptions: Thank you XXX (viewer’s name) for the donation/subscription. Two of the female streamers also used this format; however, one of the female streamers interacted with the audience by asking about their life and would reciprocate the viewer telling her “Peace and love” by saying “Peace and love” back. This indicates that female streamers demonstrate a rapport style and make an effort to build relationships in their communicative behavior. This agrees with Deborah Tannen’s claims, suggesting that women are more likely to use language to build and maintain relationships while men are more likely to use language to communicate factual information (Van Herk, 2012).

Overall vocabulary results based on teammate’s gender:

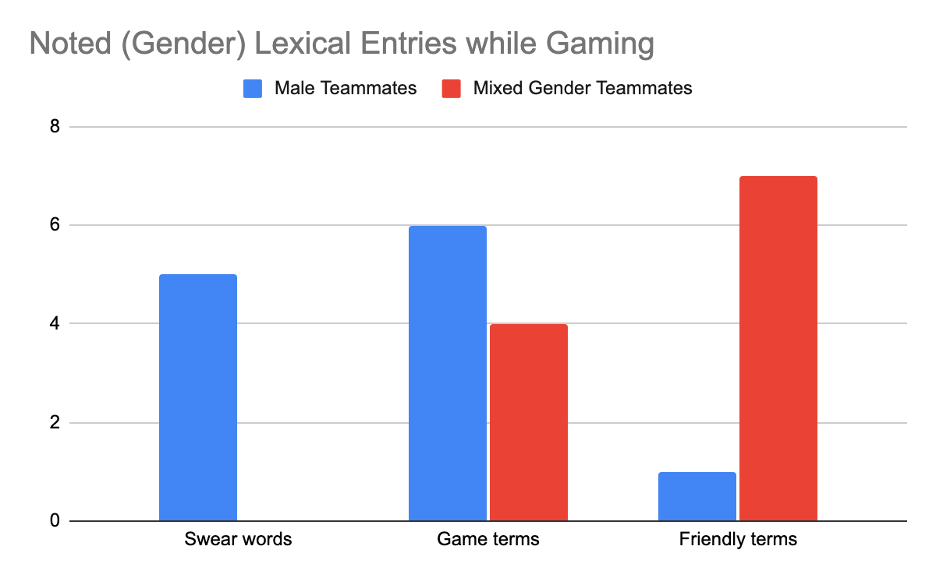

While we conducted our research, we noticed that there seemed to be a divide in gendered terms not by the gender of the streamer, but by the gender of the teammates that the streamer played with. We aggregated our vocabulary results and split them by the gender of their teammates, resulting in the bar chart below.

Streamers playing with all-male gamers said many more swear words (f*** words, sh** in particular) and gamer terms (frags, bait, camp, pick, etc), while streamers playing with a mixed-gender team did not say any swear words from our analysis and fewer gamer terms. This is due to in particular how male streamers feel the need to act more masculine and also use more common lexical entries when with other male teammates only. However, when female streamers were with female gamers or mixed gendered teammates, they tend to overall be calmer and use more relaxed language.

Another difference that was noticed was the patterns that male streamers and female streamers exhibit during the same scenarios were unexpected. For example, when male streamers and female streamers make the call-out that the enemies were attacking the B site, Kyedae says “They’re going B, right?” and Ethos says “They’re going B, they’re going B.” Kyedae said this scenario to a teammate in more of a questioning, unsure manner even though the enemies were clearly rushing B site. Ethos, however, said his callouts in a confident, command-like manner. Furthermore, what was interesting was that even if the call-out was wrong, female streamers tend to speak in a safer question-like manner, but male streamers spoke in confident manners then apologize when they were wrong.

Conclusion

Since we analyzed male and female speech in a heavily male-dominant space, we believe that our findings could apply to other male-dominant spaces. We looked at references to a similarly male-dominated industry- the sports entertainment industry. In Eastman & Billings (2000), they found that the tone used by commentators when describing male athletic wins was “enthusiastic…but derogatory” towards women’s athletic wins. This seems to relate to our findings that female streamers were more negative towards themselves and could suggest a larger connection to how derogatory attitudes towards women’s achievements in male-dominated spaces prevails and can even permeate to the women themselves. Also considering that E-Sports is still an emerging field, it’s plausible to say that the previous biases that existed in older male-dominated industries like the sports entertainment one examined in Eastman & Billings have been long established and continue to reappear today.

As for future directions, we looked mainly at the gender of streamers and controlled on popularity, the game played, and the scenarios reacted to. But through our study, we found that there were a lot more factors that could be confounding. For example, the players had varying skill levels that could have swayed our results, so we could better control for that. Another factor we saw was the gender of the teammates our streamers played with. We saw a stronger correlation between the gender of the teammates and gendered lexical entries. It would be an interesting follow-up study to analyze the interactions of an all-female team such as Cloud9 White, versus an all-male team’s interactions.

References

Çakır, G. (2021, March 5). Twitch slang and common terms explained. Dot Esports. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://dotesports.com/streaming/news/twitch-slang-and-common-terms-explained

Cameron, D. (1998). Performing gender identity. Language and gender: A reader.

Clayton, N. (2021, February 24). Valorant wants more women and ‘minority genders’ competing at its highest levels. pcgamer. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://www.pcgamer.com/valorant-wants-more-women-and-minority-genders-competing-at-its-highest-levels/

Eastman, S.T., & Billings, A.C. (2000). Sportscasting and sports reporting: The power of gender bias. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 24, (2), 192-213

How many people play valorant? player count tracker (2021). Dexerto. (2021, October 4). Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://www.dexerto.com/valorant/how-many-people-play-valorant-player-count-tracker-2021-1668158/.

Messner, M.A., Duncan, M.C., & Jenson, K. (1993). Separating the men from girls: The gendered language of televised sports. Gender and Society, 7 (1), 121-137

Nakandala, S. (2016, November 22). Gendered Conversation in a Social Game-Streaming Platform. Gender Conversation in a Social Game-Streaming Platform . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Supun-Nakandala/publication/310611118_Gendered_Conversation_in_a_Social_Game-Streaming_Platform/links/5839c31808aef00f3bfbbbf1/Gendered-Conversation-in-a-Social-Game-Streaming-Platform.pdf.

Pellicone, A. J. (2017, May 6). The game of performing play: Understanding streaming as Cultural Production. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from http://library.usc.edu.ph/ACM/CHI%202017/1proc/p4863.pdf

Takahashi, D. (2021, June 14). How riot games will ensure that Valorant’s esports stars include women. VentureBeat. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://venturebeat.com/2021/06/14/how-riot-games-wants-to-ensure-that-valorants-esports-stars-include-women/

Van Herk, G. (2012). What is sociolinguistics? (Vol. 6). John Wiley & Sons.