Megan Fu, Rowan Konstanzer, Erin Kwak, and Kimberly Gaona

Examining the speech of nonbinary individuals allows a better understanding of how different speech acoustic features such as vocal pitch, quality, and tempo are used to help construct gender identity. By investigating the speech acoustic features of non-binary celebrities, this study investigates whether coming out would cause their vocal pitch, tempo, and quality to be more divergent from cis-female and cis-male speakers. This was done by analyzing the celebrities’ pitches in their neutral interviews both before and after they publicly came out. It was hypothesized that the nonbinary individuals’ pitches would fall between the cis-female and cis-male pitches based on prior studies and research. Though this was supported by the data, a concrete conclusion was unable to be found as the differences were minor. However, an important takeaway was that a person’s pitch did not necessarily correlate with their gender identity and that there can and should be more research that includes the nonbinary community.

Key Words:

- Non-binary (or genderqueer): an umbrella term for gender identities that are neither male nor female, and identities that are outside the gender binary which fall under the LGBTQ+ community.

- Cisgender: a person whose gender identity is the same as their sex assigned at birth.

- Vocal Pitch: the low and high frequencies of a sound. Vocal pitch is determined by the degree of tension in the vocal folds of the larynx, which itself is influenced by complex and nonlinear interactions among the laryngeal muscles.

Introduction + Background:

Where there is a plethora of research regarding the vocal pitch ranges of cis-women and cis-men, there is inadequate research on the vocal pitch of non-binary individuals. We noticed this lack of information and decided to attempt to fill it. It is important to note that there are some studies that have delved into the concept of vocal pitch differences in non-binary individuals, but none that we could find that was exclusively devoted to the fact.

Using the findings from similar studies, most notably Bradley and Schmid’s 2019 study on non-binary vocal pitch and speech patterning, we were able to piece together what we thought we could expect from the results of our study. As was found in Bradley and Schmid’s study, “the non-binary group of participants had an average F0 in between the cis-men and cis-women and had intonation not patterning like the cis-women nor the cis-men—instead patterning with a mixture of both feminine and masculine traits” (Bradley & Schmid, 2019, p. 2688). While this study also looked into the vocal frequencies of cis-men, cis-women, and non-binary peoples, it focused more on the speech patterning of those individuals.

From this study and others, we were able to derive that we should expect a similar result from our research. Based on this, we hypothesized that the vocal pitch of non-binary individuals will fall somewhere in between the average F0 of women and the average F0 of men. More specifically, in the individuals that we chose to examine, the assigned female at birth (afab) individuals’ vocal pitches will deepen/lower after coming out and the assigned male at birth (amab) individuals’ vocal pitches will rise after coming out.

Methods:

In order to test our hypothesis, we chose to examine six individuals who identify as non-binary. The individuals we chose to look at where the following celebrities: Sam Smith (AMAB), Nico Tortorella (AMAB), Jonathan Van Ness (AMAB), Amandla Stenberg (AFAB), Brigette Lundy-Paine (AFAB), and Demi Lovato (AFAB). We chose to examine these celebrities because there is heavy documentation before and after they have come out, making a more thorough analysis possible. However, it is important to note that all of the chosen individuals identify as queer and that Sam Smith is British. This could have had an effect on the results and was kept in mind while conducting our research. Other confounding variables included anxiety level, heightened emotion (based on topic sensitivity), sexuality, interview setting, and level of professionalism. Thus, interviews about neutral topics were chosen, such as albums, hair, skincare routine, and TV shows. Examples of non-neutral topics that were avoided as much as possible were those about them coming out, trauma, and politics.

Two interviews before coming out and two interviews afterward were chosen for each celebrity and analyzed. After cutting the videos to exclude other speakers, audience reactions, and sound effects, the interviews were uploaded to Praat to observe the average, minimum, and maximum pitches. The minimum and maximum pitches were checked to ensure that they were from the actual subjects and not the host, audience, background music, or any other disturbances. Because there were two interviews each, the averages of the findings were utilized to compare the pitch data before and after coming out with each individual and with each other. This information was also compared to the average pitches of cisgender individuals from outside research.

Results/Analysis:

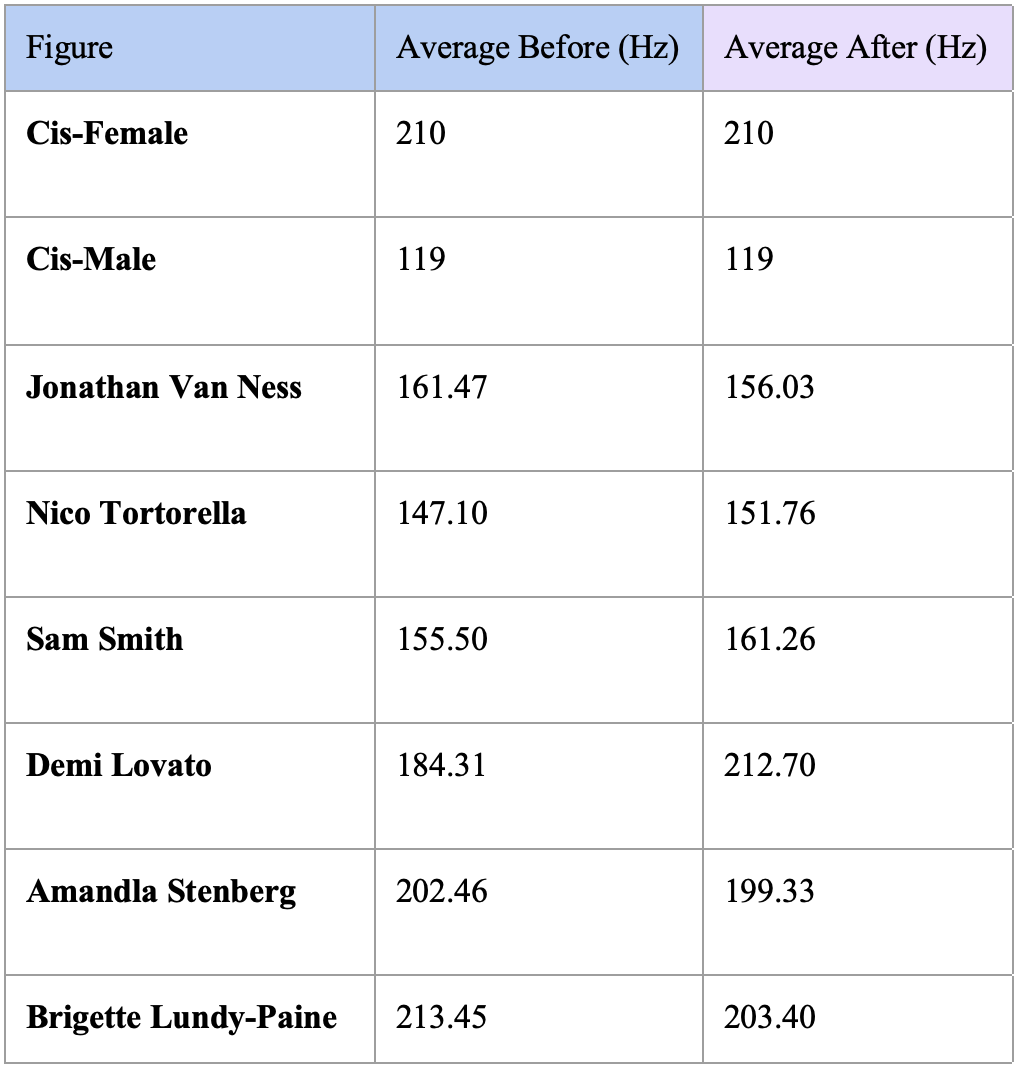

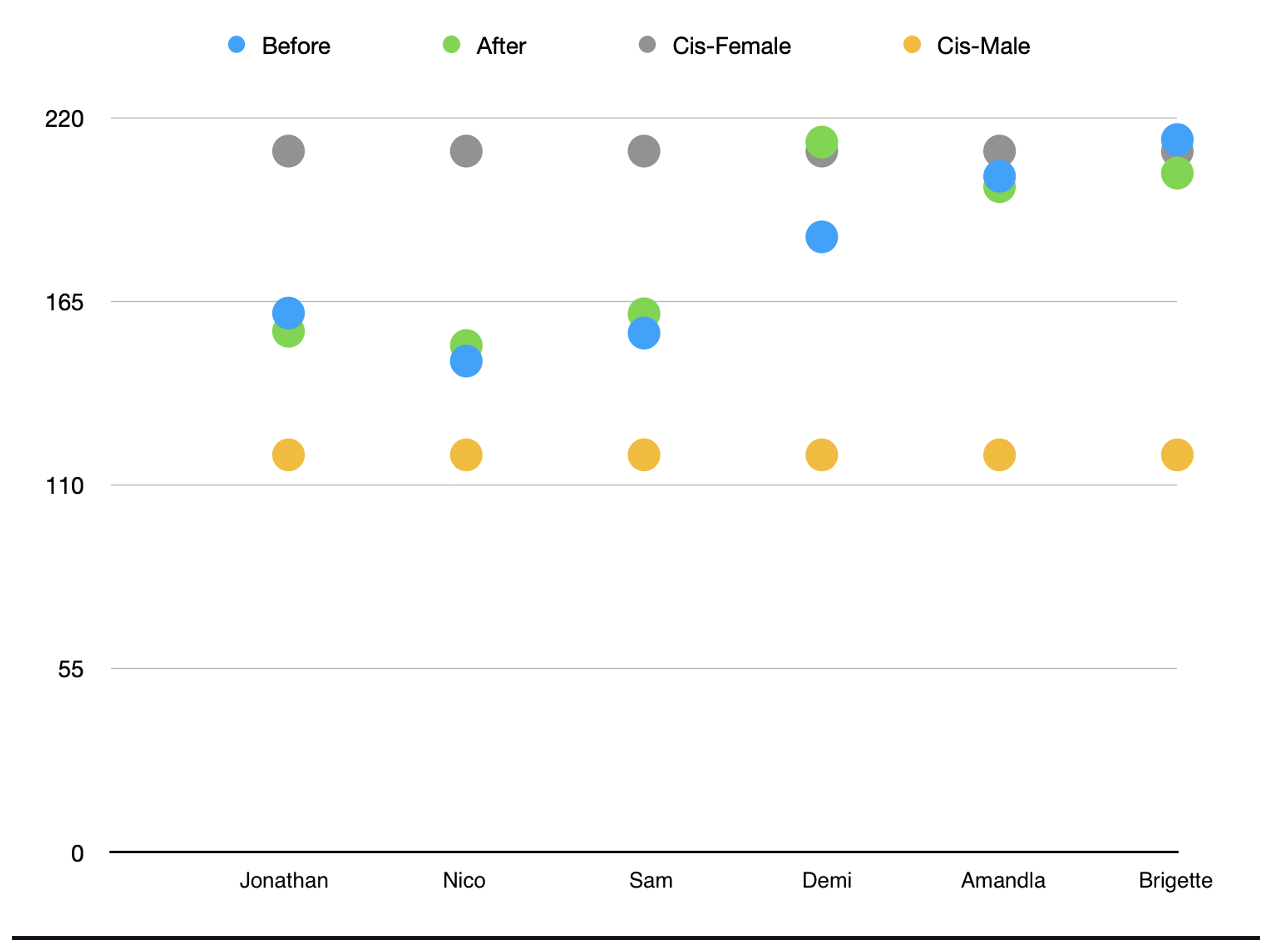

The following table and graph showcase a summary of our main findings.

Figure 1 illustrates the vocal pitches (in Hertz) of the six celebrities before and after coming out as non-binary in comparison to the female and male cisgender averages (Pépiot, 2014, p. 305). **Note that the cisgender averages do not exhibit any change before versus after.

Figure 2 depicts the same data as Figure 1 but in the form of a scatter plot so one can better visualize the change in pitch of each celebrity and see them compared against one another plus the cisgender controls. The horizontal or x-axis shows the name of the celebrities. The y-axis or the vertical axis shows the frequencies in Hertz.

Although all the celebrities exhibited some degree of change in vocal pitch, the difference was insignificant across all six individuals (the dots for most of them are overlapping). To summarize, two out of the three assigned-male-at-birth celebrities had a (slightly) higher pitch after coming out, and two out of the three assigned-female-at-birth celebrities had a (slightly) lower pitch after coming out. Even though these findings support our original hypothesis. However, the difference for each person was only a matter of <10 Hertz. For reference, with each jump in octave, the Hertz doubles. Therefore, a difference of 5 Hertz is negligible and would be indistinguishable to the human ear. Because of this minute difference in the celebrities’ vocal pitch before versus after coming out, we would say our findings were ultimately inconclusive.

We can attribute this to many different confounding variables. First, non-binary is an umbrella term so all the individuals we analyzed could fall very differently on the broad spectrum of gender identity. Because non-binary people vary in how they express their gender (or lack thereof), this could account for why the celebrities did not exhibit much change in vocal pitch after coming out. Moreover, we only analyzed six celebrities and took a small sampling of their speech patterns which limits the scope of our conclusions. Therefore, due to the small data set and population, it would be unwise to make any generalizations about the community as a whole based on these six individuals alone. Although we opted to look at celebrities’ interviews in order to get their natural speech patterns rather than elicited ones, being in a formal interview setting could have altered their pitches alone. Even though we aimed to keep the subject matter of the interviews neutral, we could not account for the individual’s mood or emotions that particular day which also could have altered their pitch. The passage of time between each set of interviews could have also had an effect on their pitch—especially considering these celebrities are on the younger side (Gen-Z and millennials), their voices could have simply matured in the time between each interview. Lastly, it is also important to note that all of the celebrities we analyzed identify as queer. Therefore, their sexual orientations could have also been a contributing factor to any deviations from the cisgender averages.

Discussions and Conclusions:

Even though we could not fully confirm our hypothesis or make any concrete conclusions there are still some worthwhile takeaways from our findings. Most importantly, one cannot make assumptions about vocal pitch based on someone’s gender expression alone. Just because someone has a higher vocal pitch does not mean they need to present more feminine or align themselves with a female identity. The same goes for a lower pitch not necessitating a masculine identity. In summary, our findings matter as they support the idea that vocal pitch is not an accurate marker of gender identity. In addition, these results combat preconceived stereotypes about the connection between vocal pitch and gender identity.

Due to the limited scope of our research, some possible future directions we thought of include doing a long-term study following non-binary individuals on their coming out journey and closely documenting any changes in pitch. Another version of this study could entail analyzing a larger population or data pool such as college students and collecting data firsthand so the environment can be more controlled since there were external factors we could not control such as background noise and interference in the celebrity interviews.

By looking at the speech acoustic features of non-binary celebrities in their interviews before versus after coming out, we were able to see analyze how their vocal pitches diverged from cis-female and cis-male speakers. Notably, researching vocal pitch differences plays a role in understanding human interaction and expression. The voice serves as a mode of personal expression for one’s identity: “the voice is a form of communication in which people form relationships with one another, show vulnerability, and show geographical linguistic features” (Mills et al., 2017, pg. 13). With this in mind, creating a study analyzing the non-binary community helps create a better understanding of the LGBTQ+ community’s expression of identity through speech acoustic features.

Through our findings, we hope to provide greater insight into the non-binary community and serve as a starting point in seeing how gender norms also play an important role in pitch production rather than assuming biology is the sole reason. Overall, we believe our research still has a purpose in opening the floor to more linguistic research into the non-binary community which often gets overlooked or glossed over.

Further Reading and Watching:

Vocal Branding: How Your Voice Shapes Your Communication Image — The voice is one of the most important factors for creating a social group, an image of oneself, and your perception of others. The different aspects of vocal pitch such as intensity, inflection, rate, frequency, and quality can say a lot about a person’s current emotional state such as being angry, sad, embarrassed, anxious, confident, happy, and so on. This is called a voice brand and helps describe a person’s personality or overall persona.

Queer Speech: Real or Not? – Languaged Life — In this blog post, you can read more about language as an identifier for sexuality. In this blog post, Dao et. al explore if there’s a difference between queer and straight women’s speech or if it is just a stereotype.

From Uptalk to Vocal Fry, Women Are Prolific Language Innovators — In this podcast, the hosts of Spectacular Vernacular engage with recent vocal trends for English speakers and how women are driving this change. Listen to find out more about the connection between communication, perception, and identity.

Watch Do I Sound Gay? | Prime Video — This 2014 documentary directed and starring David Thorpe explores the link between vocal quality and perceived sexual orientation. While entertaining, the film also explores the existence and accuracy of stereotypes about the speech patterns of homosexual men.

References:

Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies 7: 585–614.

Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Feminist Theory Reader, 519–531. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315680675-71

Erwan, P. (2014). Male and female speech: a study of mean f0, f0 range, phonation type and speech rate in Parisian French and American English speakers. Speech Prosody 7, 305-309.

Gratton, C. (2016). “Resisting the Gender Binary: The Use of (ING) in the Construction of Non-binary Transgender Identities,” University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: 22(2) , Article 7.

Gratton, C. (2015). “Recreating gender”: The linguistic construction of Non-binary Gender Identities. Poster presented at the LSA Institute 2015: University of Chicago. Work in progress.

Mills, M., & Stoneham, G. (2017). The Voice Book for Trans and Non-Binary People: A Practical Guide to Creating and Sustaining Authentic Voice and Communication. https://books.google.com/books?id=N9rADQAAQBAJ

Schmid, M., & Bradley, E. (2019). Vocal pitch and intonation characteristics of those who are gender non-binary. 2019 International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17233.68961