Adam Bouaricha, Emily Haddad, Ryan Kimura, Usuhe Maston, Natalia Adomaitis

Reportedly, 97% of young adults aged 18 to 24 are actively engaged in texting (Smith, 2011). Central to our inquiry is exploring how college students adeptly navigate misunderstandings and mend communication breakdowns within their text-based interactions with peers, friends, and romantic partners. Specifically focusing on the demographic of college students aged 18 to 22, our study delves into the myriad factors contributing to miscommunication within this cohort. Using a comprehensive mixed-method approach, we integrate surveys with picture-based evidence for enhanced analysis. Drawing upon the framework of multimodal conversational analysis, our research endeavors to unravel the intricacies of repair mechanisms, encompassing trouble sources, repair initiation, and ensuing solutions in text-based interactions. Analysis of our diverse sample of college students unveils that critical trouble sources, such as the absence of tone and social cues, substantially influence the occurrence of misunderstandings. Participants demonstrate a keen awareness of communication breakdowns, prompting proactive engagement in repair solutions to rectify discrepancies. Through rigorous thematic analysis of survey responses, we discern prevalent patterns and adaptive strategies individuals employ to navigate the complexities of miscommunication within text-based interactions. Ultimately, this study enriches our understanding of the nuanced challenges inherent in digital communication practices among college students, contributing valuable insights to the broader discourse on effective communication in the digital age.

Introduction and Background

The main problem we wanted to investigate was what factors contribute to miscommunication in our target population of college students ages 18-22, since texting (computer mediated communication) is so prevalent in our observed demographic. Our project design observed whether college students preferred texting or live conversations (face-to-face) as a means of communication. While somewhat scarce, previous research on this topic has allowed us to form a basic understanding of miscommunication over text. Studies have shown that the lack of cues, ubiquity, and brevity of interactions during CMC provide a disadvantage compared to FTF communication. Previously, students have felt that texting has both its advantages and disadvantages, and did not indicate a strong preference for CMC or FTF (Kelly et al 2012). Another study found that emojis can serve as speech acts. Emojis possess meaning and intent behind their usage, but their ambiguity over CMC is where miscommunication arises. It was shown that senders and receivers of texts both significantly overestimate the effectiveness of an emoji in conveying meaning, which can lead to miscommunication (Holtgraves 2024). Our research aims to fill the gap left by previous research, especially because much of the research on this topic is over ten years old. We also hope to narrow the scope of such a topic, focusing on a more specific group (college students), rather than a wider range of demographics. Similarly, many studies emphasize emojis and their ability to perform speech acts (Holtgraves 2024). While we do not deny the role emojis play in communication or miscommunication, we also observed the use of acronyms and slang, as well as the lack of FTF multimodal communication such as tone, gesture, and facial expression. Our paper builds on prior research to answer why online miscommunication occurs and whether CMC or FTF is preferred amongst college students ages 18-22 when communicating.

Methods

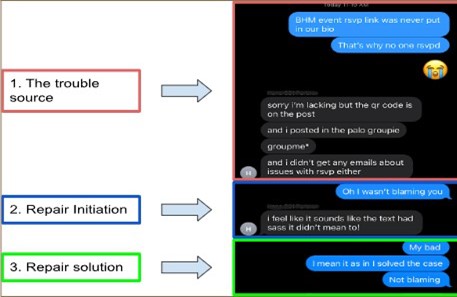

The method we used to analyze the results of our data was multimodal conversational analysis. One of the factors we mainly focused on was repair. Three components involved in analyzing repair in our data are: 1. The trouble source, or what’s causing the miscommunication, 2. Repair initiation, how the problem is being addressed, and 3. Repair solution, how do the participants solve the problem (Hoey & Kendrick, 2017). In observing instances of miscommunication from our observed community of college students ages 18-22, trouble sources such as lack of tone, social cues, body language, and other multimodal factors, contributed to miscommunication over text or as one respondent stated, “ a common issue between me and my partner is that I’m a blunt texter (no punctuation or emojis) and he’s the opposite. So my texts make him feel like I’m upset at him when in reality I’m just trying to respond as quickly as possible” (anonymous participant). While further analyzing our responses from the Google Form we sent to our participants, repair initiation typically occurred when the people involved in the conversation realized a mishap occurred. Repair solutions transpired as senders and receivers addressed what was miscommunicated and what was actually intended. As in Figure 1, an apology was used and deemed honest because one person admitted the error and explained the problem. Here is another example from our data where these three components of repair can be observed in Figure 1:

Results and Analysis

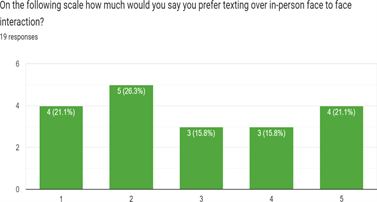

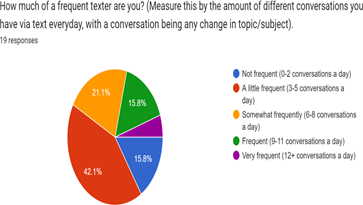

Our sample population fit our target population, with over 50% of participants being upperclassmen with all having a variety of majors encompassing STEM, the humanities, and social sciences. Figure 2 shows that 52.6% of respondents claimed that they preferred CMC over face-to-face interaction, and figure 3 shows that 42.1% text a little frequently, with 3-5 text conversations occurring a day. All but 2 respondents had listed English as their primary language, at 89% of the responses, the two outliers had put Spanish as their primary language; however, all the examples we received from participants were wholly in English. Participants were prompted to provide an example, either as a screenshot of a CMC conversation or to type out an example. The following question asked respondents to identify the miscommunication, which allowed us to better analyze and understand how they occurred. The majority of participants listed that they were close to their communication partner in their provided example, with 57.8% of respondents identifying their partner as either a friend, significant other, or family member. However, despite this closeness and increased familiarity much of the self-identified reasons for miscommunication arose from a lack of tone, or being too blunt while writing. Some wrote that their communication “[felt] like [it] had sass”, that their blunt texting style makes their significant other believe that they’re “upset at him”, and one respondent wrote that “I can never tell if they’re being sarcastic or genuine”. Other than lack of tone, the second most common misunderstanding was simply one party not being familiar with a word/phrase/acronym being used by their conversation partner.

Discussion and Conclusions

As we examine our results, we can conclude that, based on the demonstrated sample size (initially influenced by previously conducted studies citing technological relevance in effective age groups (Hemmer, Heidi 2009), there is a noticeable preference for in-person, face-to-face communication over computer-mediated conversation. As we had begun to hypothesize how the significance of multimodality comes into play in regard to the interpretation of language through CMC, contextual research, in addition to our data, has allowed us to develop a means of identifying the conditions that allow for the total utility multimodal communication, or a lack thereof within the identified samples. We attempt to examine the aspect of repair within our use of multimodal conversation analysis; recognizing the lack of physical indicators that help to form comprehendible, precise conversations within CMC, followed up with the identification of said misinterpretation of communication acknowledged by both parties, and finally, resolution of both parties being reached upon clarification. When examining the submitted data from a phenomenological lens, we identify the occurrence of these criteria from an individual yet quantified perspective.

References

Hemmer, Heidi (2009) “Impact of Text Messaging on Communication,” Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: Vol. 9, Article 5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.56816/2378-6949.1058 Available at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol9/iss1/5

Hoey, E.M., & Kendrick, K.H. (2017). Conversational Analysis. Research Methods in Psycholinguistics and the Neurobiology of Language https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_2328034_8/component/file_3513001/content

Holtgraves, T. (2024). Emoji, Speech Acts, and Perceived Communicative Success. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 43(1), 83-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X231200450

Kelly, L., Keaten, J. A., Becker, B., Cole, J., Littleford, L., & Rothe, B. (2012). “It’s the american lifestyle! ”: An investigation of text messaging by college students. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17459435.2012.719203

Smith, A. (2011). How Americans Use Text Messaging. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech; Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2011/09/19/how-americans-use-text-messaging/.