Verania Amaton, Kimberly Maynard, YueYan Kong, Yi Wang

BTS. Gangnam Style. K-dramas. Korean culture has been steadily making its way into the United States’ mainstream culture leading to more contact between the cultures and languages. Any fan of Korean media knows that Korean has built-in formality tiers, a tricky part for native speakers of English to master when learning Korean. But does the English language really lack levels of formality just because they aren’t built into its grammar? In this study, we look into alternate ways of expressing politeness in both American English and Korean. By looking at how speakers of both languages make requests, refusals, and apologies, we were able to find what types of strategies they use outside of the expected word choice and grammar. Based on our data, there are more similarities than one might expect in terms of how speakers of these languages use politeness strategies. Continue reading to learn more about how we approached a cross-cultural comparison of the politeness strategies in the U.S. English and Korean!

Introduction and Background

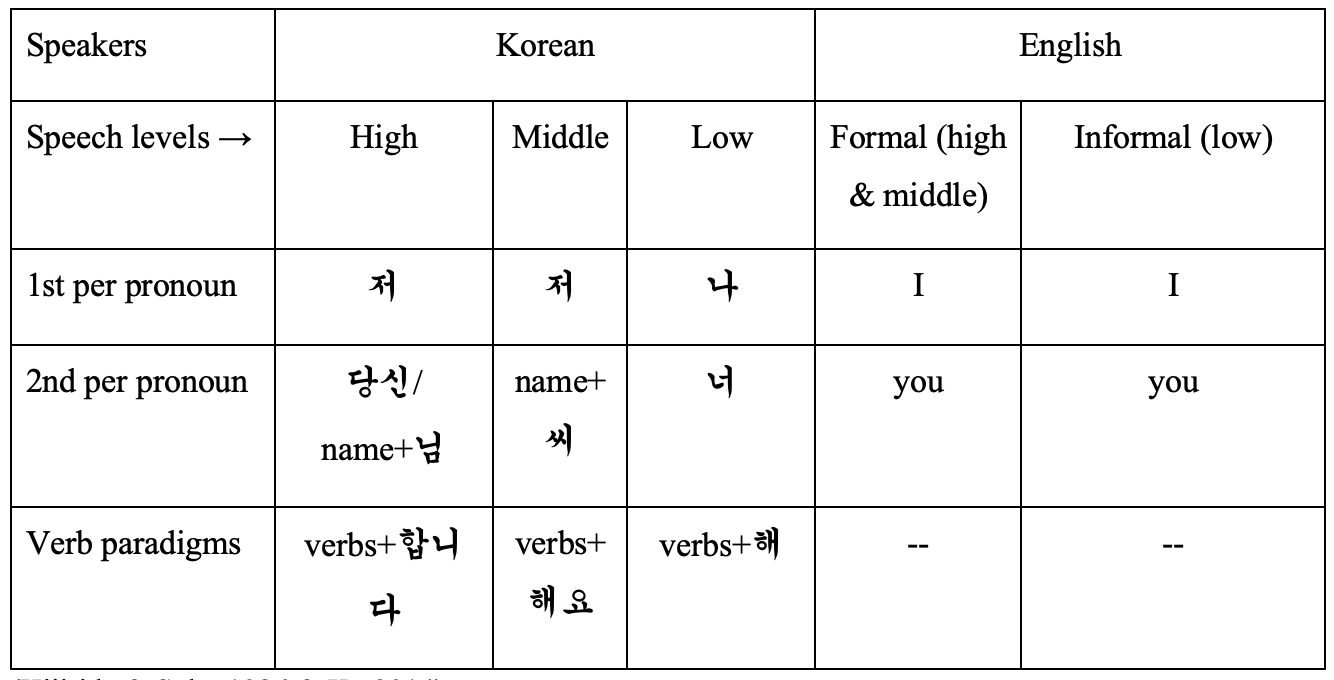

With the rise of popularity of Korean media in the United States, more Americans are being exposed to Korean language and culture. One of the most notable differences between the English and Korean languages is the idea behind formality tiers which don’t exist as clearly in English. It would be unfair to presume English speakers are inherently impolite because they don’t have a built-in formality system, so we expect they would have other strategies they could use to be polite. This leads to the next question of whether Korean would also have other strategies outside of grammar to express formality and how those strategies might compare to ones used in English. First, we looked into pre-existing research on these languages and cultures to give us an idea of what we could expect.

Korea is considered a collectivist-low-context culture which means that Koreans have a strong emphasis on group harmony and using context more so than words to convey messages. On the other hand, America is an individualistic-high-context culture in which there is a stronger focus on individuality and more responsibility falls on speakers to explicitly state their point (Cho, 2010). This significant difference in language culture feeds into unique styles to express politeness. The two major linguistic ways one can express politeness are through positive politeness, making the receiver feel good about themselves, and negative politeness, an apologetic stance to interaction based on the assumption that one is intruding on the listener (Brown and Levinson, 1987).

Given the contrasting cultures of communication, we would expect Koreans to be more vague overall and utilize more negative politeness in order to avoid being imposing while Americans would be more direct in their politeness, thus leaning towards more positive politeness strategies.

Methods

We know from intuition that regardless of culture, both American and Korean teenagers are expected to change their speech style when addressing their peers versus adults in their lives. That is why we chose to focus on collecting data from two TV series: Never Have I Ever (American English) and Inheritors (Korean), which mainly focus on the lives of teenagers. For data collection we focused on gathering pieces of dialogue that we thought could show how these characters were expressing politeness in different situations. We categorized the data into three specific speech acts (requests, refusals, and apologies) to know how politeness theory would be displayed in English and Korean. We also split this data according to the participants, specifically into peer-to-peer and student-to-adult categories1. The analysis was primarily focused on instances of positive and negative politeness, but we kept an eye out for other strategies.

Results/Analysis

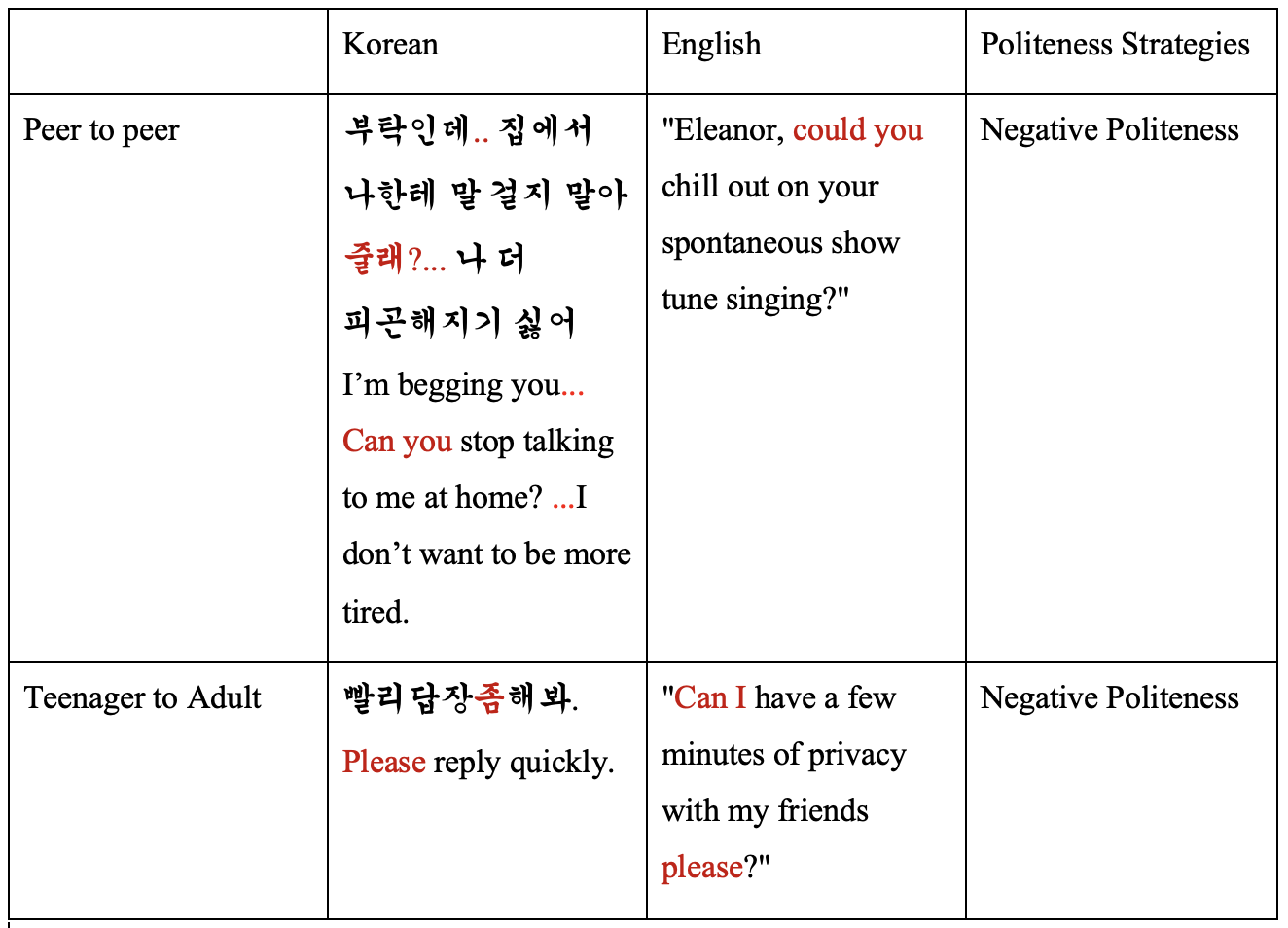

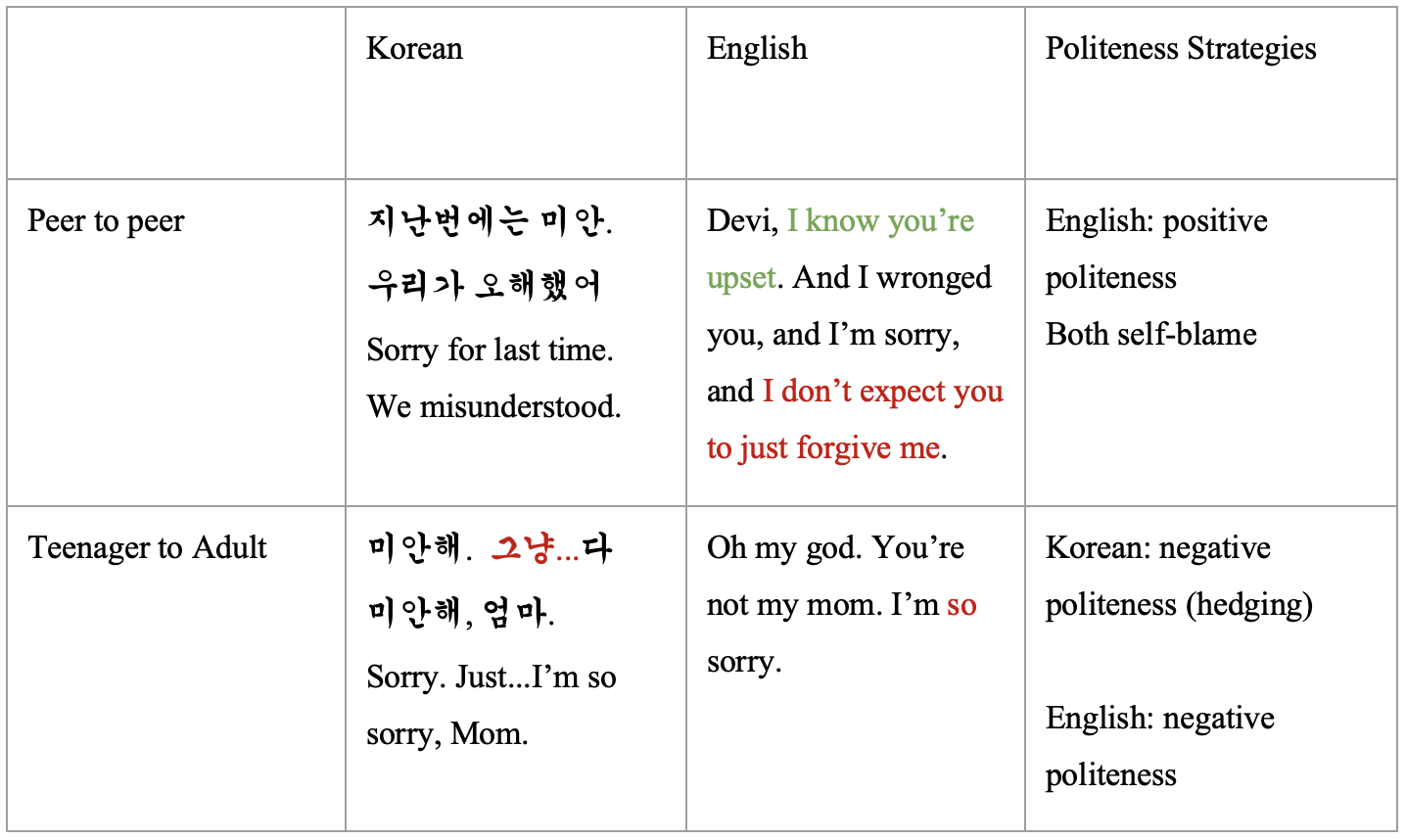

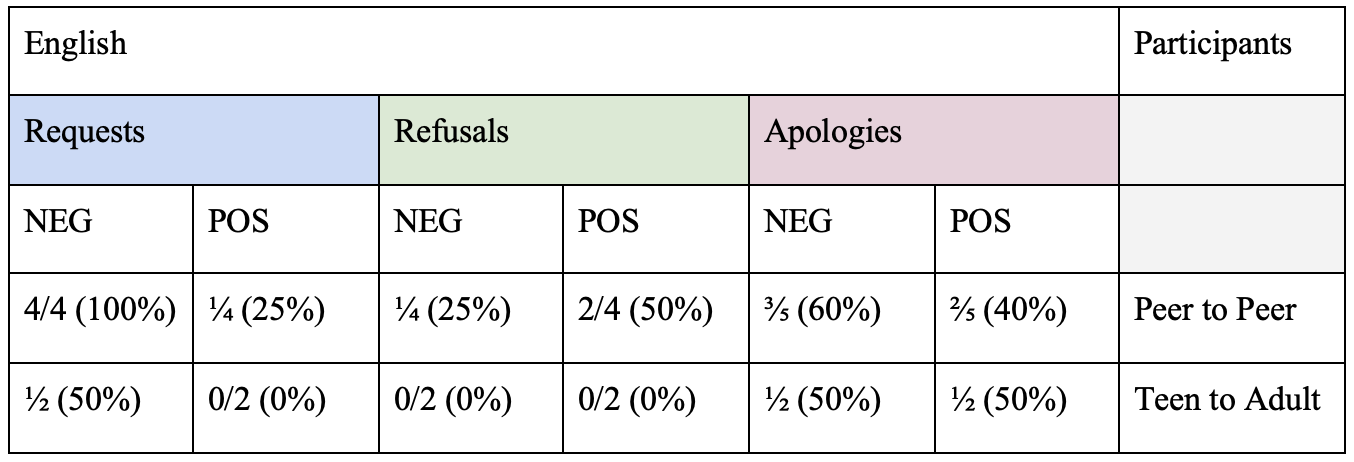

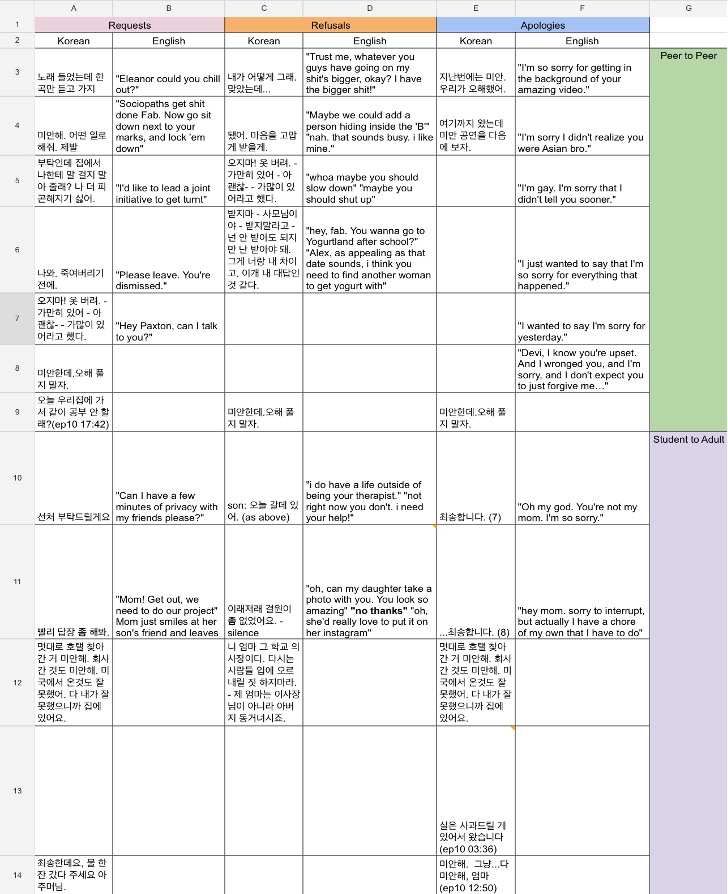

We organized our data into separate sections depending on the language, participants, and speech act. We’ll cover a couple examples for each speech act and show them in a table with some color coding to show politeness strategies used. Any negative politeness will be written in red text and positive politeness will be written in green text. At the end of this section, we will show a table that has the numbers that encompass all the data. The first speech act we looked at was requests.

In Korean we noticed the use of negative politeness strategies both between peers and between the student and adult. In the case of the peer-to-peer request shown above, there was some pausing before making the request and before explaining why the request was made. They also formatted the request as a question using “줄래? jullae?” or “Can you…” which is one way to decrease imposition or make the request feel less intrusive, thus falling into the category of negative politeness. This is similar to the use of “좀 jom” or “please” when the student is making a request to the adult, once again decreasing imposition. Something that we noticed from these Korean examples is that speakers were generally more direct than expected. In the peer-to-peer request, the student making the request explains her reasoning as her “not wanting to become more tired” which is directly related to her own wants/needs. Typically, we would expect explanations in Korean to be more vague and related to a third party or some uncontrollable situation (Lyuh 1992, p.115). Furthermore, in the student to adult example, the student used “빨리 ppalli” and “해봐 haebwa” which create a sense of urgency and is also said informally as according to Table 1. This is unexpected with a teenager approaching an adult, but we deduced that since this student was talking to her mother, the closeness of their relationship overrode the need to be more formal or polite when speaking to someone older.

While we expected more positive politeness from English speakers, surprisingly we saw a high rate of negative politeness in English requests as well. As can be seen in the examples above, English speakers tended to format their requests as questions, using forms such as “Could you…?” and “Can I…?” and again in the student to adult request we see the use of “please” to further decrease imposition. Altogether, both English and Korean showed high rates of negative politeness in their requests. In looking at the additional data, there were some instances of positive politeness in peer-to-peer requests in both languages, but it wasn’t used nearly as often in the overall data for requests.

The general trend found in Korean for refusals between students is that peers are more direct and use less positive politeness when declining something. Our example in the chart above points to the use of positive politeness in using the phrase “I appreciate your offer,” but instances such as these were uncommon across our data. Between students and adults, there was more indirect speech with an absence of positive politeness as well. One of our best examples showed the use of “I have somewhere I need to go today” from a Korean student in order to decline an invitation from his mother. Unlike in our data for Korean requests, in this instance we did see the type of vagueness or reference to an outside force when providing an explanation for something, as expected of collectivist cultures. We analyzed this as the absence of positive politeness because while it was expected he would follow up with something like thanking his mother for the invitation, he focused on his lack of time. On the other hand, we found that English was much more direct across this speech act. There are instances of both positive and negative politeness, and it varies with the speaker, context, and social distance between the interlocutors (people engaging in a conversation). In the peer-to-peer example given in Table 3 for English, the speakers are friends while the teenager-to-adult interaction is between strangers. The peer-to-peer refusal was softened by the phrase “as appealing as that date sounds,” which we categorized as positive politeness because it exaggerated how much she liked the proposed idea by her peer even if she didn’t want to accept his invitation. In the English data, the first refusal is more euphemistic and the second is more direct, but both are clearly refusals.

In the case of apologies, both languages behaved opposite from what we expected based on our hypothesis. In Korean, there was a much lower rate of politeness strategies being used overall. For example, in peer-to-peer, there was no use of negative politeness strategies. Even in the example given in the table, we were not able to identify any particular strategies being used. The apology was simple and straight-forward. We do believe it is worth noting that our data for the Korean apology section was scarce in sample size and could have had more examples, which may contribute to the low numbers we are seeing. In the case of student to adult apologies however, we did see more use of negative politeness strategies. As seen in the table, the student used “그냥 geunyang” or “just” with a slight pause during her apology. This is an example of hedging, a negative politeness strategy where one delays or lengthens their statement. In terms of positive politeness strategies, we saw them only being used in peer-to-peer apologies in Korean.

In English, the rates of both positive and negative politeness were higher than expected, leading us to conclude that in this particular speech act, English speakers may employ more outside help to achieve the purpose of their apologies. In one of our English examples for peer-to-peer, a speaker says “I don’t expect you to just forgive me” as a negative politeness strategy to emphasize that the receiver does not owe them their forgiveness.

Outside of politeness strategies we observed that in both languages there was a pattern for emphasizing the aspect of self-blame across apologies. This was achieved by explaining their wrongdoings within the apology in order to bring awareness to their guilt.

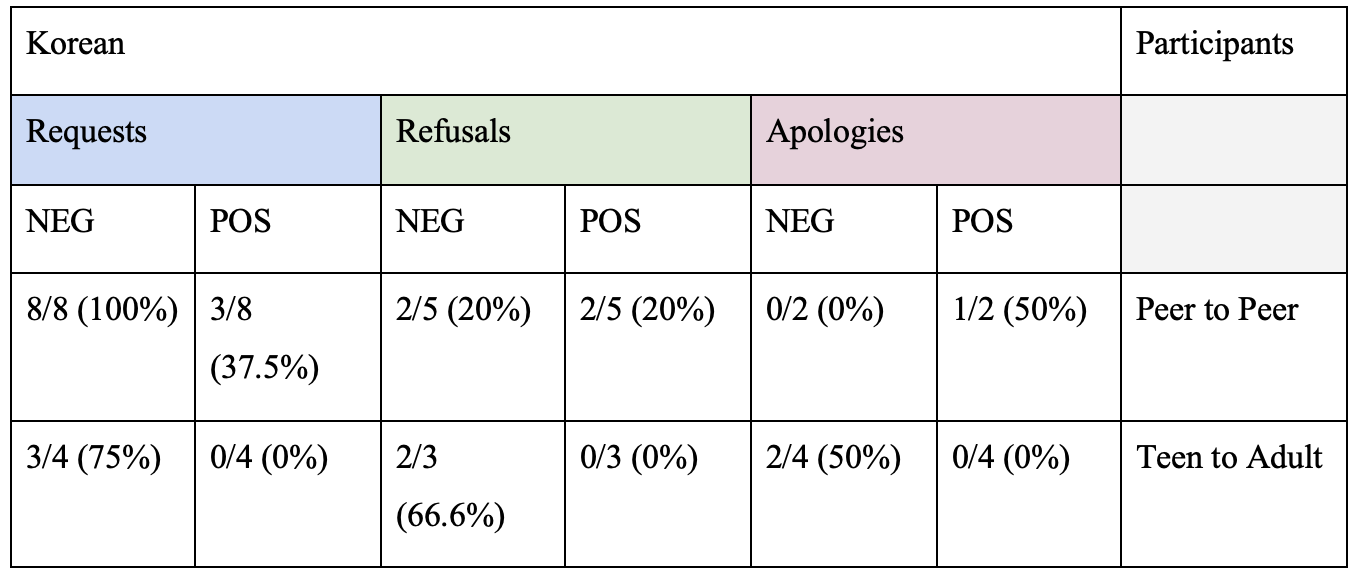

In cross comparing our data for both languages overall, we found that there was no significant difference between the rates of politeness strategies used across the three speech acts we observed. English had a 37.5% rate of politeness strategies employed overall while Korean had a similar rate of 34.9%. However, an interesting trend we could identify was that while Korean teenagers did not necessarily use more negative politeness, they did demonstrate a wider variety of it while American teenagers stuck to using the same forms in their negative politeness strategies.

Discussion and Conclusions

After we had collected all the data above, we found that some of our data was consistent with our hypothesis while other data went against expected politeness patterns. We concluded that the Korean language does use negative politeness more often than positive politeness. Still, English also had a lot of unexpected evidence of negative politeness.

In addition, the importance of politeness strategies goes beyond vocabulary and grammar. It can also be expressed through strategies such as hedging and pausing in interaction. Despite the lack of a formality system in English, English speakers can change formality and politeness through the use of these identified positive and negative politeness strategies.

Based on what we concluded above, this study could be helpful for cross-cultural interlocutors to gain a deeper understanding of the language and communication styles of different cultures. For example, it could help politicians who need to conduct diplomatic affairs and business workers of international companies. Language learners would also benefit because memorizing phrases isn’t always enough to fully understand the underlying nuances of a language. Being able to properly understand the politeness strategies used by someone else and being able to apply them yourself can help greatly decrease misunderstandings.

In the early stage of collecting data, we also encountered some problems. Since we had yet not narrowed down the speech acts to requests, refusals, and apologies at the beginning, the initial data collection and analysis was not smooth. In future research, those interested in this topic can narrow down the scope of speech acts before collecting their data and perform future studies with more reliable sources. Our data results were affected by a relatively small sample size as we could not watch entire seasons of our shows, but future studies should consider collecting data from entire seasons if time allows. Future researchers of this topic could improve the source material by utilizing questionnaires, naturalistic observations, real person interviews, a wider variety of TV shows, or unscripted YouTubers’ speech patterns to collect data for their studies.

Extended Data Table:

References

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

Cho, S. E. (2010). A cross-cultural comparison of Korean and *American social network sites: Exploring cultural differences in social relationships and self-presentation (Order No.3397528). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305224890). pp. 23-25

Ku, Jeong Yoon. “Korean Honorifics: A Case Study Analysis of Korean Speech Levels in Naturally Occurring Conversation.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2014. Print. P.7.

Kyoko Hijirida & Ho‐min Sohn (1986) Cross‐cultural patterns of honorifics and sociolinguistic sensitivity to honorific variables: Evidence from English, Japanese, and Korean, Research on Language & Social Interaction, 19:3, 365-401, DOI: 10.1080/08351818609389264) p. 370.

Lyuh, I. (1992) The art of refusal: Comparison of Korean and American cultures. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. pp. 87-117

Mindy, K., Fisher, L., Klein, H., Miner, D., Shapeero, T. (Executive producers). (2020-present)

Never Have I Ever [TV series]. Kaling International, Inc.

Yoon, H. (Executive Producer). (2013). Inheritors [TV series]. Hwa & Dam Pictures.