Kaylie Sagara

As the 2020 Presidential Election gets closer, the Democratic primary candidates are battling it out on the debate stage, which airs live to the public on National Television. While the American political system has been consistently male-dominated since the time of our Founding Fathers, recent years have shown a candidate pool that is getting closer to representing the general population, with more female candidates in the running. However, traditional gender differences illustrated in speech between men and women may affect female politicians’ ability to steal the floor during these debates. Since debates are under a strict schedule and structure, it is already difficult to squeeze in an answer between other candidates and the network moderators, so polite requests used by women are ineffective compared to the forceful demands of their male counterparts. This study analyzes and compares the turn-taking strategies employed by male and female candidates in several of the 2019 televised debates in order to interrupt or take the floor, revealing how traditional gendered forms of speech can negatively impact female politicians in this debate setting.

Background

The presidential democratic debates are tightly structured and the rules are stated directly by a moderator at the start of each debate, where amounts of time are set for answers and rebuttals, and a warning is given against interruptions. Despite the tight format, as illustrated in video compilations like this one, there are many instances when rules are broken and there is a lot of overlap and interruptions as candidates attempt to get a chance to speak. This is where we can see examples of overlap and interruptions, as well as the use of polite requests and demanding directives. The way in which candidates either demand or request time reflect overarching societal expectations of politeness on gender and power.

The two debates I have analyzed interactions from are the September 12th, 2019 debate at Texas Southern University in Houston (Fig. 1), and the October 15th, 2019 debate at Otterbein University in Westerville, Ohio (Fig. 2).

On the topic of linguistics and gender, we know that there are traditional differences in the way women and men speak, due to differences in how we are raised and taught. Robin Lakoff (1973) examines how women speak and the effect that is produced, which is a position of subordination to men because of politeness and an unsureness. However, a more recent and properly conducted study by O’Barr and Atkin’s chapter on women’s language as powerless language (1998), examines courtroom dialogue to look at language variance due to gender differences in a courtroom. They classify the features as a language of powerlessness, which can apply for men, not only women, and depends on power relationships between participants (1998, 24). Something that Lakoff (1973) examines is the use of requests and politeness, which I have examined in this study. While being wary of Lakoff’s view on classifying requests as women’s language, the use of simple requests on the debate stage is predominantly exemplified by women, whereas direct orders are rare, and are more often used by male candidates. Requests with please are described as “distinctly unmasculine” (Lakoff, 57) in a way that allows women to prevent expressing a strong statement. However, the point of the presidential debates is to make strong statements when conveying views on topical issues in order to gain attention from the public. The use of “please” and forming polite requests thus relinquishes a candidate’s ability to appear compelling and strong to viewers. In Carroll and Fox’s book (2018) on gender in elections, they note that language used in the public’s expectations about politicians and candidates illustrate a very stereotypically masculine space, where “tough, dominant, and assertive” are used to describe ideal leaders; typically gendered as male words (Carol & Fox, 2018). Gender also operates within the public’s approval of political candidates and how they should act. This traps female candidates in a traditionally feminine box, where they must act out certain womanly stereotypes and expectations in order to earn favor with implicitly biased citizens who are socialized with these ideals about gender. By examining these debates, it will help show what extent gendered speech strategies have on male and female candidates’ ability to take the floor.

Methods

I used conversational analysis conventions to transcribe the excerpts of the debate where there are significant overlap or interruptions occurring, as well as opportunities for interjection during pauses and lowering pitch, which normally occurs when someone is ending a sentence. I will also look at word choice by candidates when making attempts to get the floor, and whether or not they are successful by looking at whether or not the moderator grants them time to answer.

Analysis

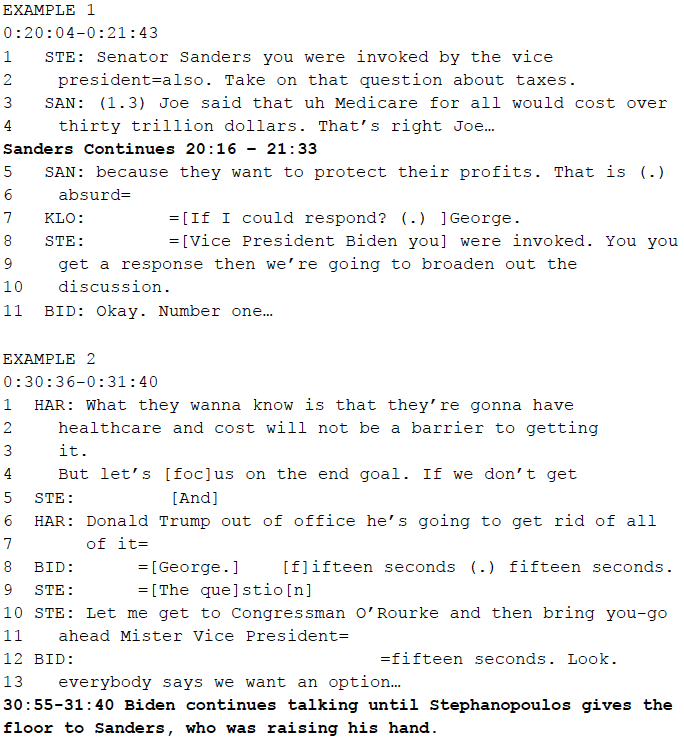

In two excerpts from the September Debate, Amy Klobuchar and Joe Biden both attempt to grab the floor, following the end of another candidate’s answer. They both engage in overlap with moderator George Stephanopoulos—who is supposed to choose the next speaker by name. These contrasting attempts at self-selection and the reaction from the moderator illustrate the importance of demands, rather than requests, when commanding authority.

We can see that in Example 1, Klobuchar attempts to enter the debate after Bernie Sander’s starts to finish his response, but she was unsuccessful. Klobuchar’s word choice in line 7 indicates politeness, using an “if I could” request to interject, instead of a demand. This request is contrasted by Joe Biden’s response in example 2 when he attempts to get the floor using a directive.In line 8, Biden says “fifteen seconds;” he is not asking, he is demanding. The strategy employed by Biden is successful, and the moderator changes his mind in line 10 to give the floor to give him the floor instead of O’Rourke. Klobuchar’s use of politeness toward the moderator designates respect, and illustrates the power to which moderators have over the candidates, as they are the ones choosing speakers and deciding when rules can be broken. Biden does not use respect, and he is ultimately successful.

Once in both debates, Kamala Harris unsuccessfully attempts to enter the conversation after another candidate’s turn is over by using phrases “could I” and “I’d like.” Both times the moderator denies her request by choosing a different speaker.

In example 3, Harris is ignored. In example 4, Harris is ignored again, but her persistence in requesting to answer results in her microphone volume being shut off. She can still be heard speaking as Lacey then refers to Biden for the next question. This transcription exemplifies the quieting of women in political arenas.

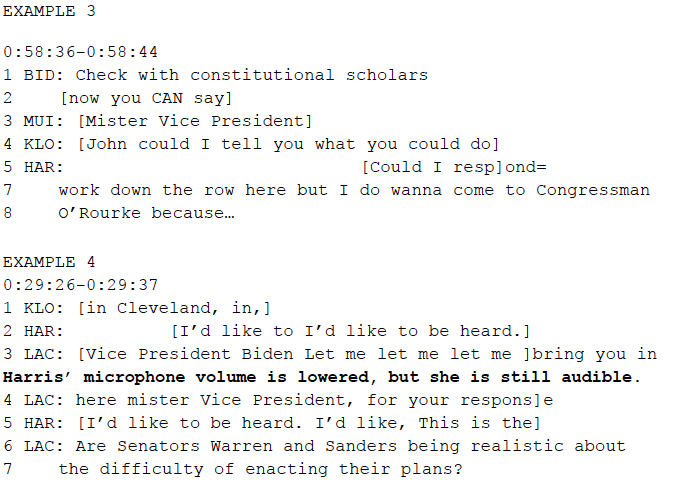

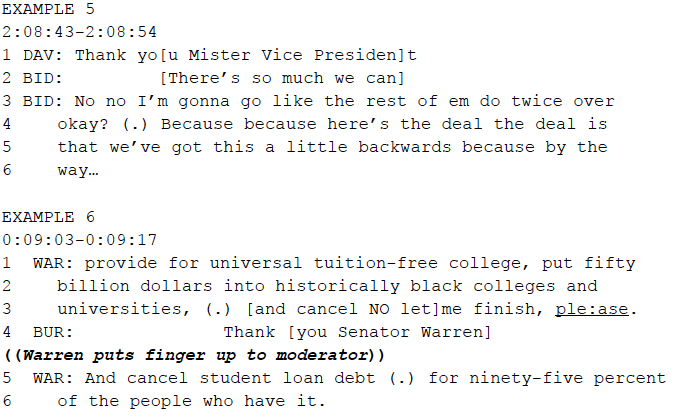

In the next examples, we see the candidates verbally deny the moderator’s request to choose a new speaker by using masculine, demanding tones.

In example 5 from the September Debate, Biden does not allow Lindsey Davis to fulfill her role in choosing the next speaker because he was not done answering. Instead, he references the previous candidates who also overlapped with moderators and continued answering despite attempts to give the floor to someone else. Biden is direct and firm in his speech in line 3, saying “No no” to the overlap by Davis, to which she allows. In example 6, from the October Debate, Elizabeth Warren also states “no” and raises her voice when moderator Burnett starts to overlap her speech and firmly denies the attempt at selecting a new speaker and is eventually successful in standing her ground. However, she ends her firm statement by using “please” in line 3 to prevent the command from sounding too assertive. This goes back to the idea in Gender and Elections that female candidates cannot adopt the demeanor of male politicians to become equals (Carrol & Fox, 2018). Rather, they have to play into public ideas of women in power and what normal citizens expect to see and hear from a woman.

Conclusions

The goal of the debates is to allow Americans to hear the candidates’ platforms, as well as assess their ability to command respect on stage through articulate speech. As seen in the transcription examples, it appears that male candidates tend to speak with more demand than the female candidates, and are also able to take the floor more often than women. This goes back to the theme of politeness, and the societal expectation that women use “feminine” speech that projects a tentative and unsure quality.

The ability of each candidate to select themselves when a new turn is beginning is not exactly reflected in the overall time spoken during these debates. In Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, there is varied distribution for speaking time between the female and male candidates, with Biden and Warren switching off between the top two spots for both debates, so we cannot explicitly correlate gender and gender strategies of speech with ability to get time on the stage, since both candidates show different approaches to turn-taking in the above examples and had different success rates in interrupting. However, we can use these transcriptions to show that gender stereotypes in language do persist and are evident in formal, traditionally male settings like these debates. As the democratic debates and primary elections end, the persistence of misogyny and scrutiny over female politicians is exemplified in the two last candidates standing; heteronormative, white male candidates Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden. As more women run for elections in the future, methods of speaking and taking the floor may become more similar between male and female politicians, and will hopefully allow women leaders to contribute to changing power dynamics, shifting stereotypes about women in leadership roles, and thus affect linguistic strategies and norms.

References

Carrol, Susan J. & Richard L. Fox. (2018) Gender and Elections: Shaping the Future of American Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, Robin (1973). Language and Woman’s Place: Language in Society 2 (1): 45–80.

O’Barr, William M., and Bowman K. Atkins. (1998) Language and Gender, A Reader: Women’s Language or Powerless Language? Malden, MA: Blackwell. 377-387.