Wenqian Guo, Sum Yi Li, Yichen Lyu, Sok Kwan Wong, Yingge Zhou

Code-switching has become increasingly common as globalization allows international exchanges across cultures to take place more frequently. And as studying abroad becomes more accessible to students around the world, more speech communities with distinctive code-switching patterns are being formed. As we pondered the topic for our research project, we looked around and realized that not only are the majority of our group members native Mandarin speakers studying in the US, but collectively we also belong to this wider speech community that tends to code-switch between Mandarin and English. We could not help but wonder — do local students in China talk like us at all? And is there a reasoning behind the way we talk? It is these questions that formed the basis of our research.

For the project, we narrowed down our research to focus on just Internet slang used on WeChat, China’s answer to WhatsApp. Through our proprietary survey and by combing through chat history we collected from our participants, we discovered some very interesting findings. Continue reading to find out how and why Mandarin-speaking international students in the US code switch on WeChat.

Introduction and background

Chinese students who study in the U.S. often code switch between Mandarin and English and our project was aimed at examining the motivations behind the phenomenon.

We specifically looked into our subjects’ texting patterns on messaging app WeChat and compared them to Chinese students either residing in China or other non-English speaking countries in an attempt to confirm our assumption that code-switching is prevalent among Chinese students in the US. We also surveyed the students and asked for reasons behind their choice of words. We hypothesized that convenience as well as a desire to appear foreign-educated are what motivated the code-switching.

We based our project on Luke’s (1984) study on language mixing in Hong Kong, where English words are often inserted into Cantonese conversations. Luke (1984) concluded that code-switching in Hong Kong is partly pragmatically motivated (when the objects being discussed do not have Chinese translation) and partly socially motivated (when the individuals want to identify as better educated and westernized).

We extended Luke’s (1984) study to cover Mandarin Chinese, which is spoken in Mainland China. Presumably English mixing is more prevalent in Hong Kong because it is a former British colony. Code switching is not common among locals in China, but it is observed among individuals who have exposure in English-speaking countries.

Methods

The target population for our project consists of two major groups: college students who study in the US and college students who study in their home country China. Both groups of students are native Mandarin speakers. Our data collection was divided into two parts. First, we created a survey to ask both groups of students to select from provided word choices under different text conversation scenarios and provide us with a reason behind each choice. The participants were also asked to specify how frequently they would code-switch in their daily conversations with friends and family on WeChat. Second, we collected a series of chat history based on three main topics, namely schoolwork, casual conversations and sensitive topics. For the survey, we interviewed a total of 17 students from UCLA as our sampling for the groups of students who are foreign educated. We also interviewed a total of 6 college students who are based in China.

Results

For the purpose of discussion, our project referred to college students who study overseas as “US students” and those who study in China as “local students”.

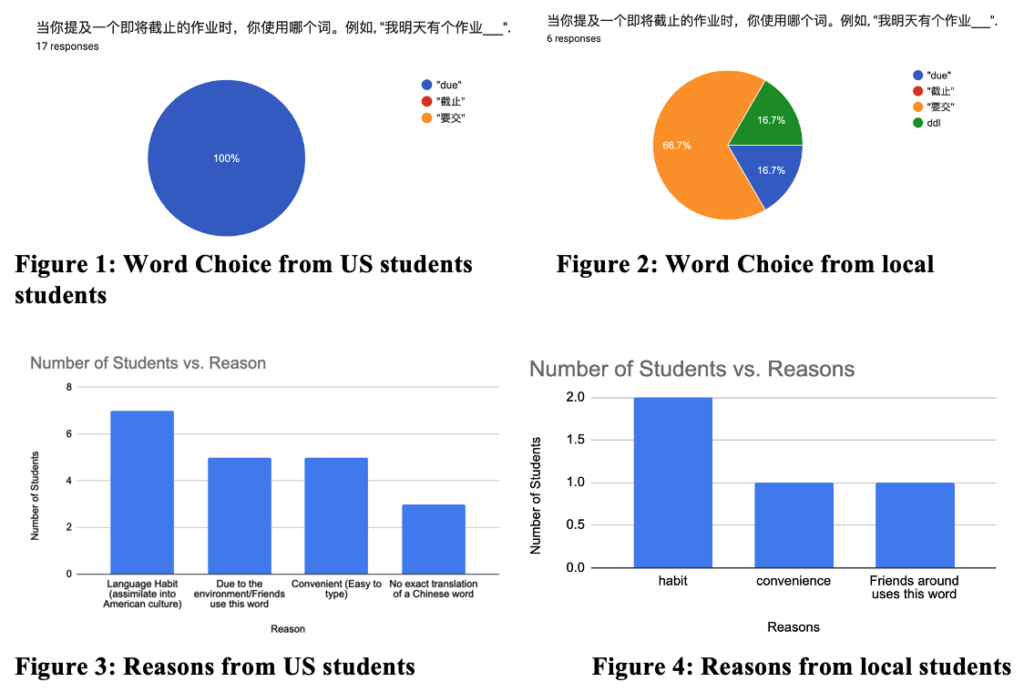

School Work Survey Question 1: Which word would you use when you want to talk about a homework assignment that will be due soon. For example, “我明天有个作业___”. (Tomorrow I have some homework__)

For the first survey question regarding homework assignment, all of the US students chose the English word “due”, while the majority of the local students chose the equivalent Chinese words “要交”. Even though most students from both groups attributed their choice to a similar reason, which is language habit, from the perspective of the US students, “language habit” refers to a way to try to assimilate into the American culture, while in the context of the local students, it is more of an innate and natural habit.

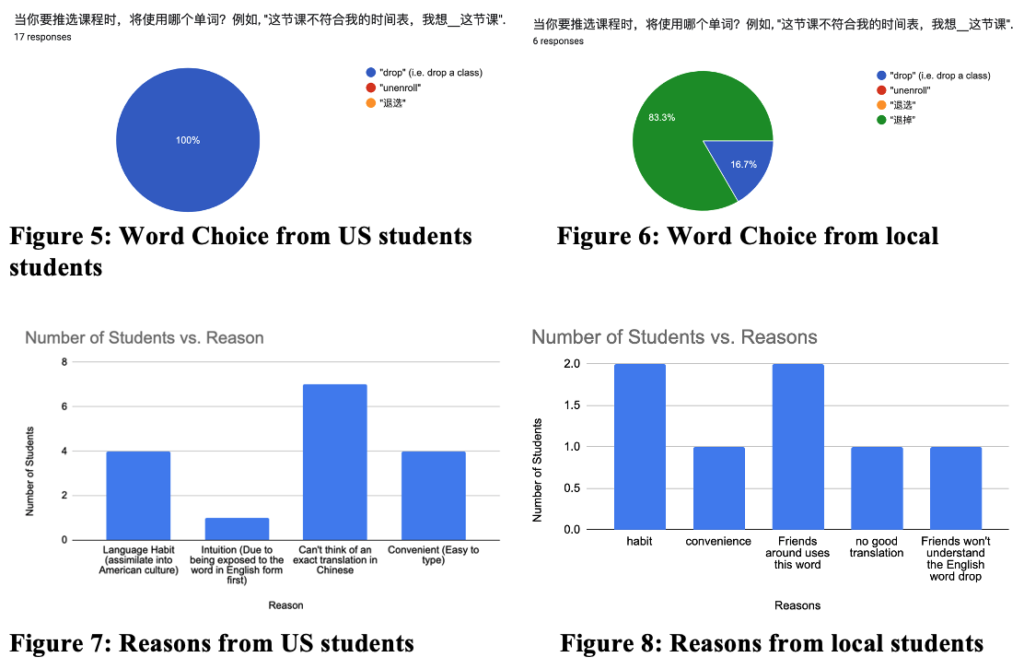

School Work Survey Question 2: Which word would you use when you want to unenroll a class you have registered before? For example, “这节课不符合我的时间表, 我想__这节课”. (This class doesn’t match my schedule, I want to __ this class.)

For the second survey question relating to unenrolling classes, all of the US students chose the English word “drop”, while the majority of the local students picked the Chinese equivalent “退选”. However, both groups have different reasons behind their word choice. The majority of the US students said they chose the word “drop” because there is no equivalent translation in Chinese. On the other hand, the local students preferred using Chinese due to language habits influenced by their friends and family.

Based on the reasons the participants provided, it appears that being in different environments and different speech communities are the main reason students develop different language habits. Besides, the source of learning also influences their word choices. The US students tend to find it hard to find Chinese translation for words related to schoolwork since they learned these words in an English-speaking environment.

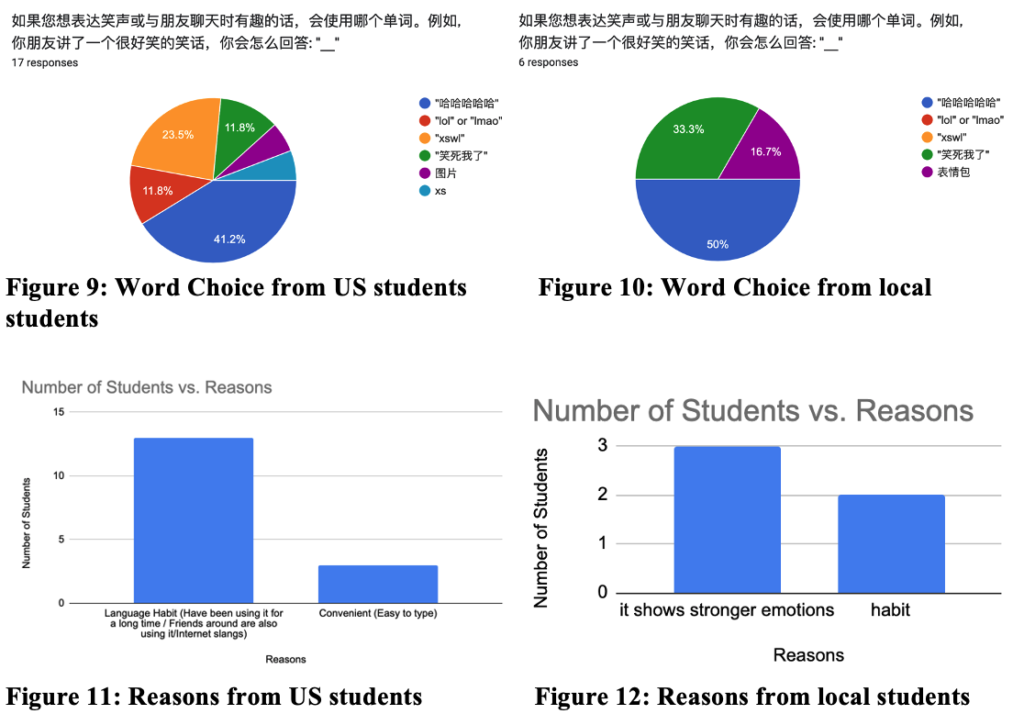

Casual Conversation Survey Question 1: Which word would you use if you want to express laughter or something that is funny when you are chatting with your friends.

When asked how they would express laughter when texting, the majority of the US students chose the Chinese words “哈哈哈哈” (“Hahahaha”), while the majority of the local students picked another Chinese phrase “笑死我了” (“I laugh to death”). Even though both groups of students used Chinese to express laughter, each side has their own reason for the specific choice. The US students said they preferred “哈哈哈哈” (“Hahahaha”) as a language habit, while the local students preferred “笑死我了” (“I laugh to death”) because they believed the expression could better demonstrate their emotions and the situation. The results showed that Mandarin-speaking college students preferred to use Chinese when expressing laughter regardless of where they are studying.

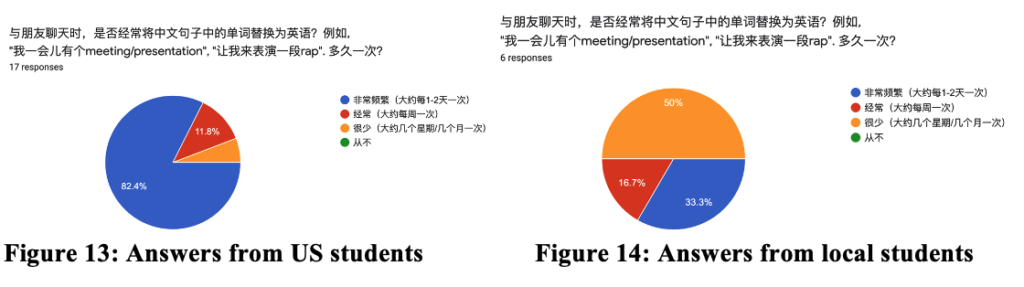

Casual Conversation Survey Question 2: How often do you often replace words in a sentence from Chinese to English when you are chatting with your friends? For example, “我一会儿有个meeting or presentation”, “让我来表演一段rap”.

When asked how frequently they code-switch between Chinese and English when texting their friends and family, the majority of the US students said at least once every one to two days. Meanwhile, half of the local students said they seldom code-switch — only at least once every few weeks or months during their daily conversations.

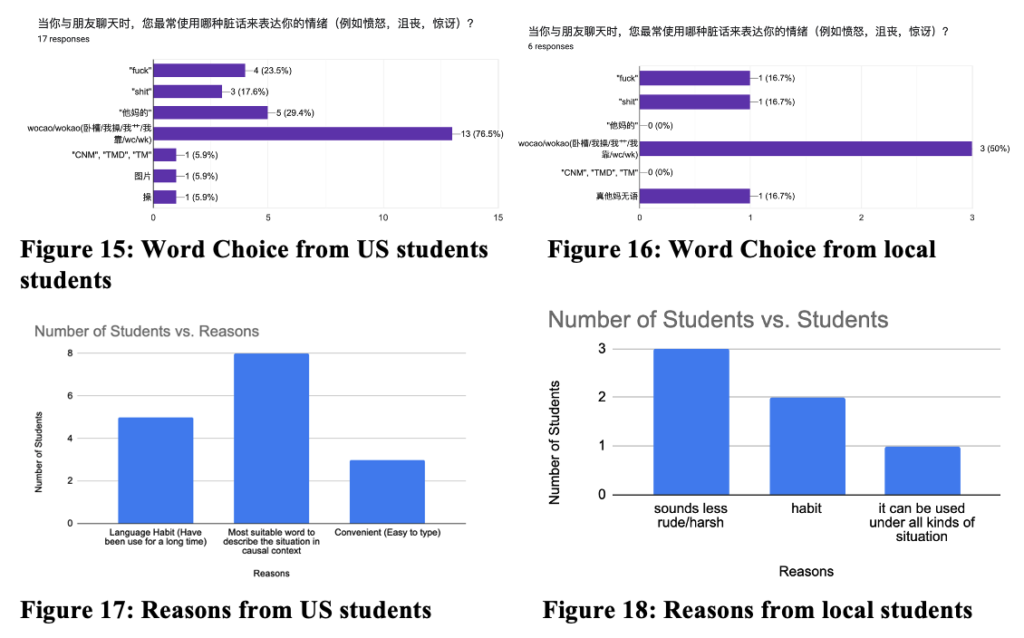

Sensitive Topic Survey Question 1: What kind of curse words would you use most frequently when you are chatting with your Mandarin speaking friends?

When asked which curse words they most frequently use, both groups of students chose “卧槽/我操/我靠” (roughly translated as “Damn it/Fuck”) but for different reasons. The US students said this option best describes their feelings, while the local students said it sounds less harsh than the other choices.

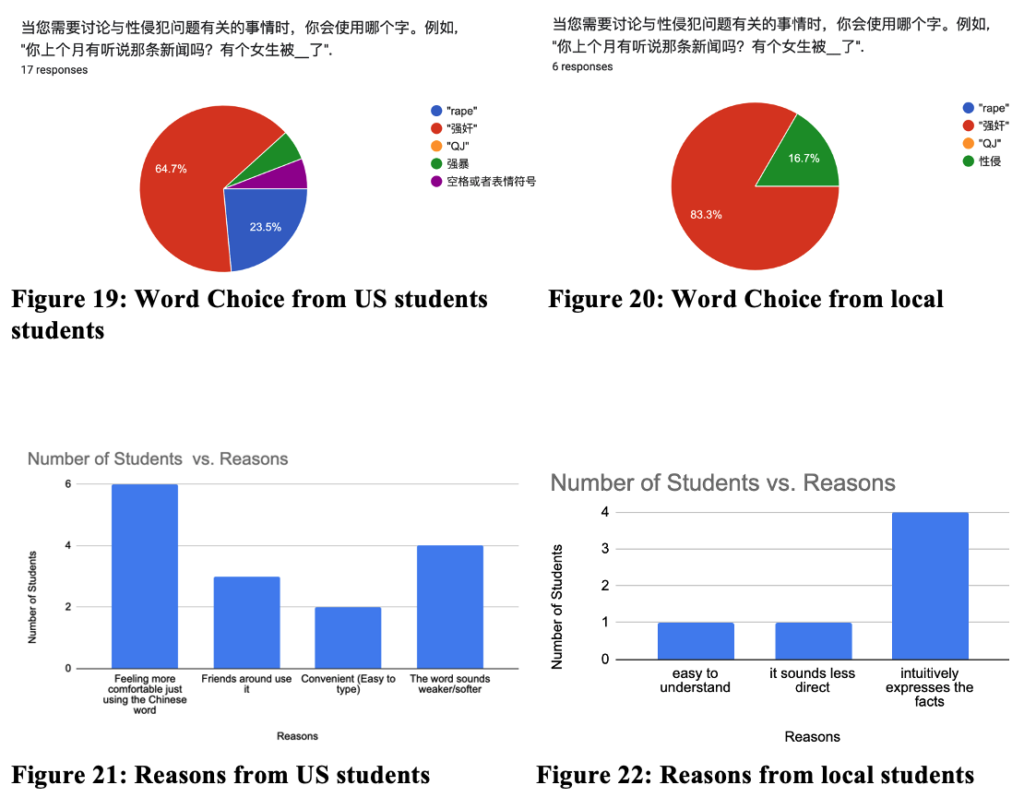

Sensitive Topic Survey Question 2: Which word would you use when you need to discuss something that is related to the issue of sexual assault. For example “你上个月有听说那条新闻吗?有个女生被__了”. (Did you hear the news? A girl was __)

When asked what words they would use to say “rape”, the majority of both the US and local students chose the Chinese words “强奸”, instead of “rape” in English or the abbreviation “QJ”. Most local students said they did not worry whether the word sounds too direct or inappropriate but would rather want to just say what really happened. Similarly, the US students said they felt more comfortable with the Chinese words.

Our survey: English version and Chinese version

Chat History Analysis

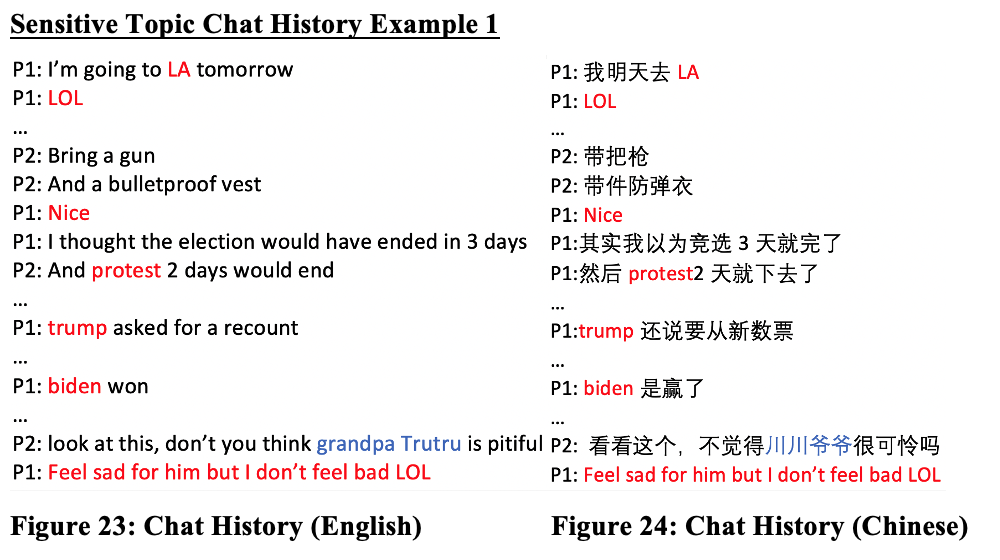

The chat history was obtained from Chinese students studying in the US. The words marked red were originally in English, while those in black are translations from Mandarin.

This is a conversation between two participants about the recent US election. P1 said they expected people to stop protesting in two days. Instead of using the Chinese words (“游行”) for protest, P1 code-switched from Mandarin to English. Since protests are rare in China, and the Chinese words for protests are rarely used, presumably it is easier for the participant to just use the English word when texting.

Marked code-switching is observed when P1 expresses a slight disagreement with P2. As P2 feels empathetic to Trump, P1 emphasizes with English to express that they don’t feel sad for Trump’s loss.

Another interesting point is that P2 referred to Trump as “Grandpa Trutru”, his Chinese nickname. Chinese people sometimes use nicknames to refer to important politicians, which is likely stemmed from China’s censorship on sensitive topics. Discussions about certain politicians are considered highly sensitive, so to avoid censorship, they come up with nicknames for the politicians. For example, Trump is also known as “懂王” (“the king who knows it all”), while Biden is “睡王” (“the sleepy king”). The use of nicknames exudes a sense of humor as well as dials down the seriousness of the discussion of political issues.

In casual conversations, code-switching again lends convenience and gives emphasis. It also constructs a common identity among people in the conversation. In the above conversation, the participant is telling a story about their roommate being forcefully taken away to the hospital after answering routine behavioral questions wrong, which is a well-known cultural shock among Chinese students studying in the US. As this routine is not performed in China, the participant constantly code-switched on noun and verb phrases for convenience. Also, all participants of this conversation are Chinese international students. The code-switching builds a common identity among them because the participant expects everyone to know the consequences of answering yes to routine behavioral questions. The last two sentences are examples of marked code-switching that emphasize on the participant’s disbelief: The participant is surprised that his roommate answered yes. It is a final revelation of the ending to this anecdote.

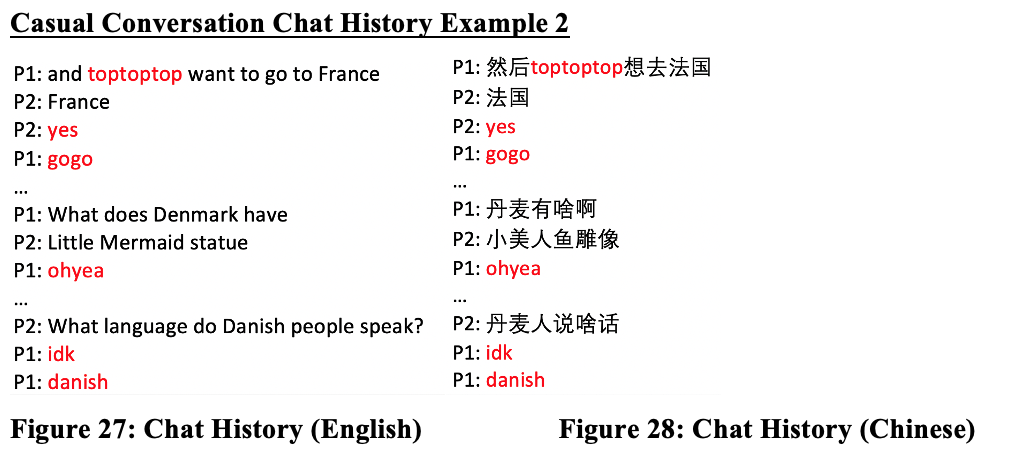

Similarly, in the above conversation, code-switching again serves as building a common identity among Chinese students in the US. The participants constantly chose to use short English vernaculars, such as “yes,” “go,” and “yea.” This indicates that they have been immersed in an English-speaking environment, so when expressing agreement and excitement, they tend to code-switch to English. Also, P1 ignored all English spacing in the conversation. This is because when typing English with the Chinese keyboard, adding spacing can be time-consuming. For convenience, P1 simply ignored the spacing during texting. Even so, P1 chose to respond in English, demonstrating that it is more natural for them to use these English vernacular phrases.

In academic scenarios, code-switching almost entirely occurs in jargon. By using English jargons such as “peer interaction” and “mutual engagement”, the participants demonstrated their educational background as foreign.

Discussion and Conclusion

From the aforementioned data findings, it can be concluded that Chinese students who study abroad and those who only study in China show different patterns in their language usage. When it comes to schoolwork and casual conversations, insertions of English words into Chinese sentences and code-switching between English and Chinese are mainly observed among students who study abroad, while less so is seen among the domestic students. This difference can likely be attributed to a lack of translation equivalence, as many school work-related words are only applicable in the US. The same goes for casual conversations. It is therefore not difficult to understand why the US students would tend to code-switch to English when there seems to be a lack of translation equivalence in Chinese.

Besides, the needs for social and emotional expressions evoked by surrounding cultural environments and contexts also contribute to the different language patterns and code-switching. In China, a conservative country both culturally and politically, pro-government language is encouraged, while the freedom of speech is repressed. This repression has in turn cultivated stronger needs for expressing emotions among the local students, leading to their choice of more confrontational and direct wordings when discussing sensitive topics. On the other hand, a higher frequency of code-switching among the US students revealed their needs to be identified as foreign-educated and share common identities with other speech participants of similar backgrounds.

Our findings point to the important roles that social surroundings and the kind of language encouraged within these environments could play in one’s speech patterns and code-switching. That being said, the language choices that the participants made are not entirely dependent on their own characteristics but are rather choices commonly negotiated by one’s surrounding social context as a whole. This contextual-based understanding therefore sets a reminder for future conversation analysis and sociolinguistic study, that one’s speech patterns could not be analyzed and identified without incorporating the nature of the surrounding speech contexts and cultural environments.

More on the topic:

Video about attitudes toward code switching in China

Paper on Chinese-English code-switching in conversations

References

K.K. Luke (1984), Expedient and Orientational Language Mixing in Hong Kong, York Papers in Linguistics 11, 191-201