Danbi Jang, Tomoe Murata, Mayu Yamamoto, Gale Nickels

This research study investigates how young men and women in relationships react toward typos and seeks to identify any differences. Based on previous research findings, we hypothesized that women are more likely to retype typos compared to men since men have been shown to communicate primarily for practicality, while women have been shown to put more social importance on texting. An alternative hypothesis we investigated was that as the intimacy levels and mutual understanding increase within the relationship, both partners prefer to leave typos uncorrected. To test these hypotheses, participants were asked to fill out a survey, asking about the length of the texting and relationship periods, how close they think they are with their partner, and what they prefer to do when they make typos. They were also asked to share screenshots of typos where they misspelled a word. The results indicated that women had a higher rate of correcting typos than men, which supported our hypothesis; however, the difference was not substantial enough to make a conclusion. We did find, however, that intimacy levels had a much stronger correlation with typo correction likelihood. Thus, the main finding of our study is that intimacy is the best factor in predicting whether the person corrects or leaves typos in relationship-based text messaging, not gender.

Introduction

There is no doubt that texting is the dominant form of written communication of our age. Depending on who you ask, by comparison, emailing and letter-writing seem formal at best, and antiquated at worst. Young adults between 18 and 24 are estimated to send about 110 texts per day (Smith, 2019), which is reflected in endless pop culture references to mobile phones and SMS. For instance, Lana Del Rey in “Take Me to Paris” sings, “Text me when you get home safely,” summarizing one of many social rituals that have arisen from text communication. Texting is a key daily ritual in most communities all over the world.

However, unlike face-to-face communication, texting achieves something unique: documentation. The recipient of a text can take a screenshot and collect ‘receipts’ at any moment, so it is more important than ever that the social face a text communicates is exactly as intended. Another example of this in the music industry is presented by Drake in “H.Y.F.R:” “…That’s when I text (sic.) her and told her I love her, then right after texted and told her I’m faded,” demonstrating how accountability in texting can be circumvented by claiming lack of sobriety and other means. So, texting conveys many layers of nuance and social significance that might not be apparent at first glance. However, texts are shot back and forth so quickly that a problem often arises: typos. They can usually be quickly remedied by retyping the offending word with an asterisk appended, but even the act of correcting a typo holds implications. For instance, leaving a typo can be perceived as comedic or aloof, while retyping it might convey earnestness or carefulness. This led us to question if certain people are more likely to correct or leave typos depending on their individual traits. Specifically, we targeted the groups that are thought to text each other most frequently: couples.

When discussing romantic dynamics, gender is often a key focus of previous research. In the past, it has been shown that in text messages, females tend to emphasize visibility while males emphasize utility (Ilie et al., 2002). This indicated that women are inclined to organize their messages in such a way that their meaning and intentions are best conveyed. Another research study found that women have been seen to use texts as a means of promoting and maintaining social relationships at a higher level than men (Aning & Yaa, 2022). If it is true that women tend to place more emotional and social importance on texting than men, this may be a reason for them to take errors more seriously and cause them to retype. Thus, we hypothesized that women are more likely to retype or correct mistakes than men when they make a typographical error in a text message.

However, we found it important to explore possibilities outside of gendered explanations as well. Our alternative hypothesis is that as the level of intimacy within a relationship increases over time, both partners correct less frequently. We predict this may be the case as over time, couples might have a better understanding of each other’s texting style, leading to a higher threshold for typos needing clarification. Also, as the relationship progresses, couples have had time to adjust and feel more comfortable within the relationship. Thus, we approached addressing these two hypotheses with a specific question in mind: Is gender a good predictor of typo correction in texts between couples?

Methods

To investigate those hypotheses, we targeted a population consisting of men and women in their early 20s who are in a romantic relationship. Another criterion was that they text their partners in Standard American English every day; however, it was not a requirement that English be their first language. We specified the age as 20s and the language as Standard American English to narrow our population to Generation Z and Millenials, as these are the groups that have had the most exposure to digital communication in their lifetimes. Additionally, this research study chose to target heterosexual, gender-conforming couples. This limitation might have been a source of selection bias; thus, we recognize that the patterns we find within these pairings may not translate when extrapolated to couples outside of this binary. Exploring outside of this subpopulation with regard to romantic texting trends may be an interesting candidate for future research.

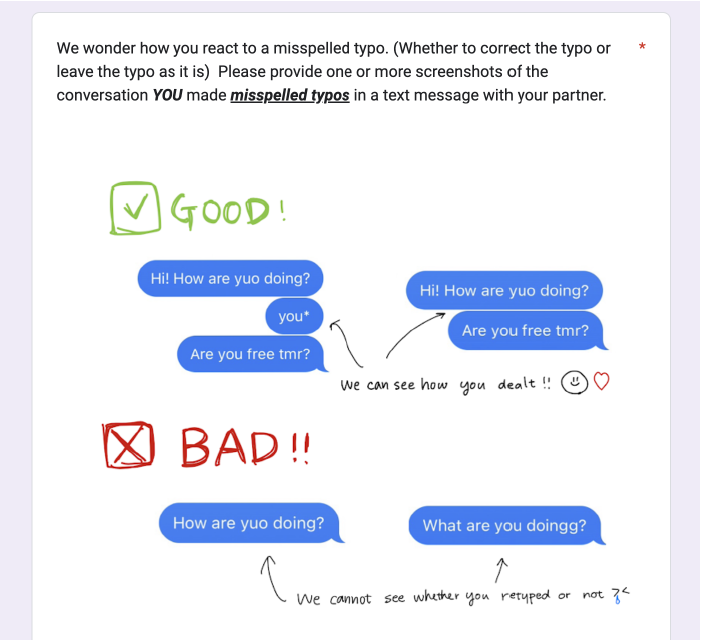

We recruited the participants by posting the survey on the UCLA Linguistics Discord server, Instagram stories, and Slack chats with students at UCLA. The way of gathering responses on listed social media is considered to be the most effective since our targeted population is the young generation. For the data collection, we utilized a multi-faceted strategy similar to that which is employed by Wagner et al. (2022). The total data set we collected included 22 responses: 10 from males and 12 from females. First, participants were given a survey that collected information about the length and nature of the relationship, as well as open-ended questions about their reactions to their typos. Next, they were asked to submit one or more screenshots where they made a non-grammatical spelling mistake, corrected or otherwise, as shown in Fig 1. We defined a typo in this research as an unintentional misspelled word, not a grammatical typo. Intentional errors for the sake of showing cuteness or aloofness towards their partner were also excluded. It is possible that the nature of the messages could have affected the content of our data. That is, participants might have excluded typos that were particularly embarrassing, which might lead to biased data; however, for the purposes of this study, we considered this to be potentially beneficial for targeting the social aspect of typo correction instead of the practicality aspect.

Particularly embarrassing typos may include big spelling mistakes that are incomprehensible and thus must be corrected for the message to be understood. If these sorts of typos are less likely to occur, we speculated that the collected data might be of better quality. Thus, the omission of embarrassing responses was not mitigated in the data collection process.

Results & Analysis

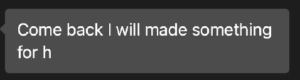

From our 22 participants, we collected a total of 25 screenshots: 14 from women and 11 from men. Two excerpts of these screenshots from our data are shown in Figures 2.1 and 2.2.

In addition, since all respondents indicated they are texting in standard English, all responses are included in the analysis. The participant responses to each question varied widely, suggesting a diverse range of intimacy and familiarity levels within our participant pool. Participants ranged from 11 to 96 months of knowing their partner, 6 to 96 months of dating, and 3 to 96 months of texting.

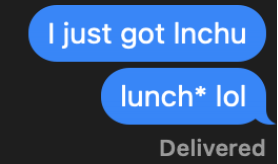

First, to test our first hypothesis that women are more likely to retype or correct errors than men, we began by analyzing the responses of each gender.

Figure 3 above shows the percentages of responses to the question about whether or not to correct the typos in the survey for males and females, respectively. As the figure shows, 58% of women correct typographical errors, while 40% of men do so, suggesting that women are more likely to correct typographical errors and seemingly supporting our hypothesis. However, given that the difference between the gender is only 18% and that more than 40% of women leave misspelled words as is, it may not be sufficient to conclude that it is a strong predictor. Thus, we decided to test whether intimacy level is a good predictor, as predicted by our second hypothesis.

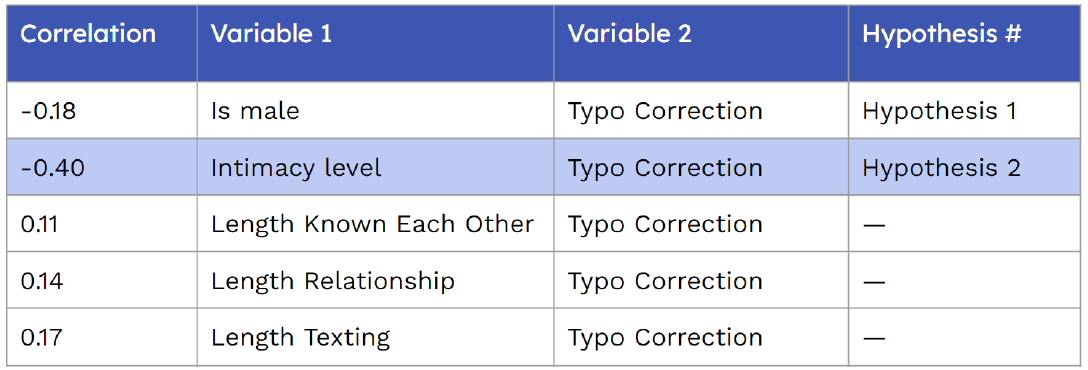

To test whether the more intimate one feels, the less likely one is to correct a typo in a message; we obtained correlation coefficients. Because the period of knowing each other, dating, or texting may be more strongly correlated with typo correction than the intimacy with the partner, they were also included as variables in addition to intimacy. The correlation coefficient between gender and typo correction is also calculated. For the analysis of the correlation values, a positive value signifies that an increase in one variable increases the other variable, and if the value is negative, an increase in one variable decreases the other variable. Furthermore, the closer a value is to positive or negative 1, the stronger the correlation is.

Figure 4 summarizes the correlation coefficients of each variable to typographical correction. First, a moderate negative correlation with a coefficient of -0.4 was identified between self-reported intimacy levels and the likelihood of correcting typographical errors. In other words, as intimacy increases, the likelihood of correcting typos decreases or vice versa, which supports our second hypothesis. Now, our remaining question, whether gender is a valid predictor of the likelihood of correcting typos, turned out to be largely uncorrelated since the coefficient is -0.18, although these two are indeed negatively correlated and better predictors than the length of the relationship, period of texting, and how long it’s been since they met each other.

Discussion and conclusions

After finding the correlation coefficients for our variables, we saw that gender was not actually a very good predictor of the likelihood of correcting typos. While it was a stronger predictor than the length of the relationship and how long it has been since they met each other, it is still very weak.

So, we concluded that our second hypothesis, that intimacy would be a better predictor of typo correction likelihood, was better supported. We found a moderate negative correlation between self-reported intimacy levels and the likelihood of correcting typos. That is, the more intimate a partner rated their relationship, the less likely they were to correct a typo. This finding makes sense in the context of prior research, which has shown that as romantic relationships develop, linguistic behaviors become more similar between couples. So, this could suggest that time allows for an increased understanding of language between partners and conversations that reflect a common outlook (Brinberg & Ram, 2021). The relationship between self-reported intimacy and the correction observed in our study suggests that the need for clarification over typos may have decreased as a result of an increased understanding of each other’s language.

Furthermore, these findings show us that the subtleties and subconscious behaviors we exhibit around our romantic partners are not static. The way we text in a relationship likely has much more to do with the person we are texting and how comfortable we are than any one personality trait. Also, thinking back to the findings of previous studies, our results suggest that the “rules of texting” that Wagner et al. proposed (2022) might not apply accurately to longer-term couples, as our findings imply that the implicit social behaviors that Wagner et al.’s rules define might change as intimacy levels grow.

References

Aning, E., & Bediako, Y. A. (2022). Gender differences in Short Message Service texts among Sandwich students: a Sociolinguistic Analysis. IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science, 27(1), 48–56.

Brinberg, M., & Ram, N. (2021). Do new romantic couples use more similar language over time? Evidence from intensive longitudinal text messages. Journal of Communication, 71(3), 454–477. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqab012

Ilie, V., Van Slyke, C., Green, G., & Lou, H. (2005). Gender differences in perceptions and use of communication technologies. Information Resources Management Journal, 18(3), 13–31. https://doi.org/10.4018/irmj.2005070102

Smith, A. (2019). How americans use text messaging. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2011/09/19 /how-americans-use-text-messaging/

Wagner, T., Punyanunt-Carter, N., & McCarthy, E. (2022). Rules, reciprocity, and emojis: An exploratory study on flirtatious texting with romantic partners. Southern Communication Journal, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794x.2022.2108889