Brooke Lim

The fact of the matter is, we have all at some point said a casual ‘bitch’ or ‘fuck’ during a conversation with both new and old friends. But does that make the other person in the conversation look at us under a new light? Profanity is a crucial part of our society’s language expression, even having a grammatical structure of its own (Bergen, 2016). With only a handful of exceptions, across time and most cultures, use of language that has been seen as profane has been discouraged by a bulk of the living society. Whether it is being chastised for saying ‘shit’ at the dinner table by your mom or being given detention by your teacher for saying ‘motherfucker’ during class, many have experienced being overtly and even covertly reprimanded for their use of obscenities.

Introduction and Background

First impressions are shaped by a myriad of superficial ideals. Whether it is the way someone presents themself physically (Willis & Todorov, 2006), how they are described by others (Asch, 1952), or even the way one shakes another person’s hand. These opinions are established based on mostly shallow facts. Similar to physical appearance, language use can also determine what particular opinions are formed.

This research proposal mainly intended to gain insight into how word choice influences judgment when used during social situations by examining if it alters one’s impression formation. The main goal was to better understand the attitude people have about profane words by assessing the reactions the general public has to curse words.

A couple of studies have already been done on the relationship between profanity use and speaker perception, the most notable, in my opinion, being ‘Language Choice Matters: When Profanity Affects How People Are Judged’ (DeFrank & Kahlbaugh, 2018.) To very briefly summarize, the study found that there is indeed a link between profanity use and poorer perceptions against the speaker. Additionally, it was also found that those use profanities were generally seen as nonconforming, less intelligent, and less friendly. However, it disregarded the speaker’s gender when examining the influence profane language has when used during conversations and the disparities that may come with it.

In addition to what DeFrank and Kahlbaugh have researched, I would also like to explore the relationship, or maybe the lack of a relationship between profanity use and speaker perception and how different gender identities might also shape judgment.

My first hypothesis was that overall impressions against the speaker using profane language will be the poorest amongst the other speakers. I also hypothesized that participants that are regularly exposed to profanities (whether they use them or hear them), are more likely to form impressions that are neutral to the speakers using obscenities. Lastly, I hypothesized that female participants will rate male speakers with more poor/negative ratings compared to female speakers. The main question I intended on answering with this study was, ‘Does using profane language change the way one is perceived by others?’ I also aimed to answer a subset of questions, ‘Does regular exposure to profane language skew one’s ability to form a negative opinion against users of profanities ?’ and ‘Is there a general consensus that male speakers using profane language will be rated poorer compared to their female counterparts?’

Methods

I used an online survey which was sent out through text and social media. Participants were asked to evaluate the vulgarity of 6 (Fuck, Bitch, Shit, Asshole/Ass, Motherfucker, Pussy) of the most commonly used swear words in California using Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (not vulgar) to 10 (extremely vulgar.) I chose to omit slurs.

Participants were also asked how frequently they use and hear profanities. Afterwards, participants were presented with a set of conversations, all being slightly altered versions of the same conversation with and without the use of profanity alongside substitutions for their more ‘inoffensive’ counterparts. The speakers were paired as follows: male/female, male/male, and female/female. Also included were certain conditions where no speaker is using profanity, one speaker is using profanity, and two speakers are using profanity. Each of the aforementioned conditions occurred in all of the previously mentioned speaker gender pairings. To circumvent any variables, the core content of the conversations remained strictly consistent. The ONLY variable that was adjusted was whether there is or there is not profane language being used. Additionally, the conversations a participant interacted with were randomly decided through an online random number generator. Participants were then asked to rate a speaker on trustworthiness, intelligence, and friendliness. The conversation below was presented to the participants.

Using Google Forms, I was able to collect voluntary response samples from my target population (18 – 25 year old non-religious native US California English speakers.) A total of 138 responses were received. 37 responses from males and 101 responses from females. Collecting the data through an online survey was the most reliable way to address my RQ. Creating controlled contexts was easier, and so was operationalizing the responses I received.

Results and Analysis

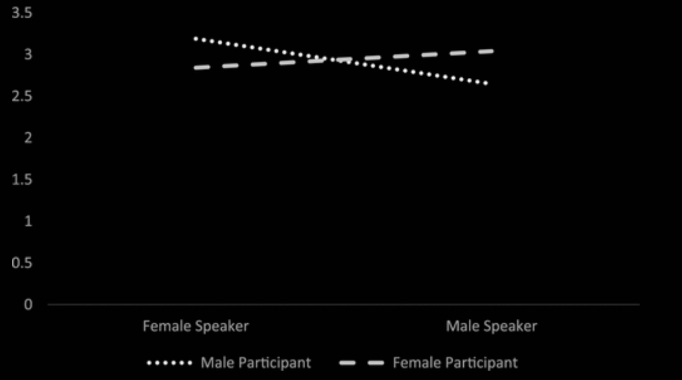

On average, male participants saw female speakers. Female participants saw male speakers were more offensive in context than they rated male ale speakers as more offensive in context than did female speakers.

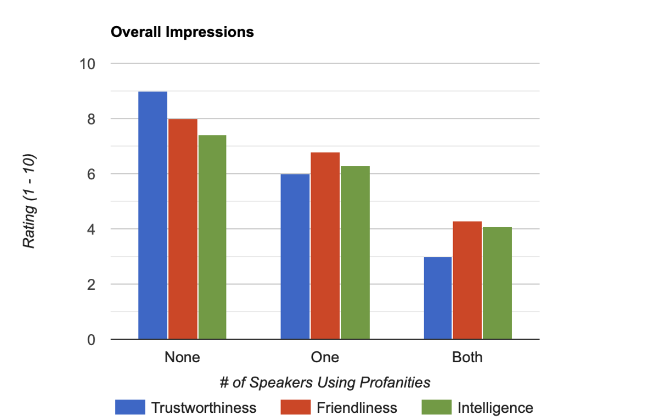

On a (1 – 10) scale, ratings were generally higher when none of the speakers were using profanities, and significantly lower when both speakers used profane language (independent of gender).

I recorded and analyzed the level of exposure to profanities on a daily basis as well as the frequency at which the conversation speakers were being rated on a scale of 1 – 10. Additionally, I recorded and analyzed the frequency of female participants rating male speakers more offensive than female speakers and vice versa.

Discussion and Conclusion

The use of obscenities DID result in less favorable impression ratings of the speaker in overall impression on intelligence, trustworthiness, and friendliness (See Figure 2). There was no evidence that regular exposure to obscenities meant neutral impressions against profane language users would be formed. Female participants saw male speakers more offensive in context than they did with female speakers and the same goes for male participants seeing female speakers as more offensive (See Figure 1).

Profanity use leads to poorer impression ratings, independent of the speaker’s gender. Profanity creates the perception of vulgarity, which in turn leads to the impression of reduced trustworthiness, sociability, and intelligence, no matter the gender.

Just a little extra random fun fact that came out of my survey’s data that I couldn’t fit into my presentation! The word that was found to be most vulgar amongst the participants of my survey was ‘bitch.’ If I’m allowed to speculate, I believe this could be due to the word ‘bitch’ having a derogatory connotation towards women specifically, and I had a lot more female participants, more than half, make up the study pool. Furthermore, I also found a pattern in which female participants rated ‘bitch’ and ‘bastard’ more offensive than the male participants in the study, which may reinforce my earlier speculation. But of course there is no true evidence behind what I’ve said, but I think future research about this topic would lead to some interesting results.

The limited male responses from the data collected leads some results to be interpreted with caution! Future research could examine the specific categories of profanity to determine if words from different categories differ in their power. Implications from this study and future research can help with understanding how language choices affect the way people are judged.

Similarly, another study conducted by Paradise, Cohl, Zweig (1980), found that, no matter the gender of profane language speakers, the act itself, the use of obscenities, led to impressions of reduced competence and less positive overall impressions.

I believe that these findings as well as my study’s data are indispensable in garnering a much deeper understanding of how one’s presentation of self and how someone chooses what words to say affects perception in ways that are fully unknown.

The words someone chooses to use will not only leave an emotional impact (which could be another topic for the future), but also a potentially long-lasting impression that may be difficult to alter. It is important to understand what image language projects and to understand that word choice/language choices DO matter.

References

Asch, S. E. (1952). Social Psychology. Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/10025-000

Bergen, B. (2016). What the f: What swearing reveals about our language, our brains, and ourselves. New York, NY: Basic Books.

DeFrank, M., & Kahlbaugh, P. (2018). Language choice matters: When profanity affects how people are judged. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 38(1), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927×18758143

Paradise, L. V., Cohl, B., Zweig, J. (1980). Effects of profane language and physical attractiveness on perceptions of counselor behavior. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 27, 620-624.

Willis, J., & Todorov, A. (2006). First Impressions. Psychological Science, 17(7), 592–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01750.x