Michelle Johnson, Kayla Sasser, Lucy (Chenyi) Wang, Grace Shoemaker, and Lien Joy Campbell

Even though the sad emojis in that exchange were used in a sad context, many people might laugh or find that inappropriate. Whether you are one of those people or someone likely to use emojis just like “Mom”, read on. As texting has grown to be a more popular form of regular communication, it may seem as if connecting with people has only become easier – but with ubiquity comes complexity. And if you are not among those at the vanguard of these complexities (the youth), you could be missing out. This brings us to the question: does expressing humor over text vary by generation? In this study we focused on Generation X and Generation Z’s use of emojis, emoticons, and other ways they chose to convey humor and tone in texts. In focusing on humor we were able to analyze the frequency of humor makers and their meanings in context. Based on our data, we found that there were definite differences in how the generations use and react to text language. Keep reading to learn what these key differences were and how we studied them (and maybe how to finally make that teenager in your life laugh).

Intro and Background

Generation Z (those born between 1997 and 2012) grew up and learned how to communicate post-advent of the invention of instant messaging. Their texting style and speaking styles are intertwined and take inspiration from each other. On the other hand, those of Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980) had to transfer previously-established styles of humor and communication to the new technological medium (Downs, 2019). This accounts for the disconnect between considering texting to be a form of writing (like an email or letter) and considering it simply as talking put onto a screen. The term “written speech,” coined by John McWhorter, gives a name to the adaptation of texting to account for all the complexities of face-to-face communication that change how the content of a message is received: emotion, formality, humor, tone, body language and facial expression. Across platforms from iMessage to TikTok, young texters use unspoken and quickly changing combinations of punctuation, capitalization, and symbols to directly translate trends and slang into the digital world.

Methods

Following our belief that Gen X and Gen Z would communicate humor over text in significantly different ways and a path laid out by a study conducted by Sánchez-Moya and Cruz-Moya (2015), we chose to create a survey that focused on responder’s opinions on texting and their texting habits. We specifically targeted people’s habits in the use of humor markers like emojis and typed laughter by asking them to choose the most appropriate option to represent a feeling or as a response to various tonal and emotional contexts. Once we had our responses, we organized our data in terms of type of marker (emoji/emoticon/capitalization) and focused on whether the marker was used literally or creatively in relation to each generation. We expected a wider range of responses in Gen Z and more similar, literal responses from Gen X.

Results and Analysis

We began our analysis by categorizing the responses we received in terms of whether they were literal or not, and we additionally compared the use of emoticons and capitalization. Further, we then also analyzed the frequency of answers we received for each question. We will present examples of each of these analyses and the contexts in which they were applied.

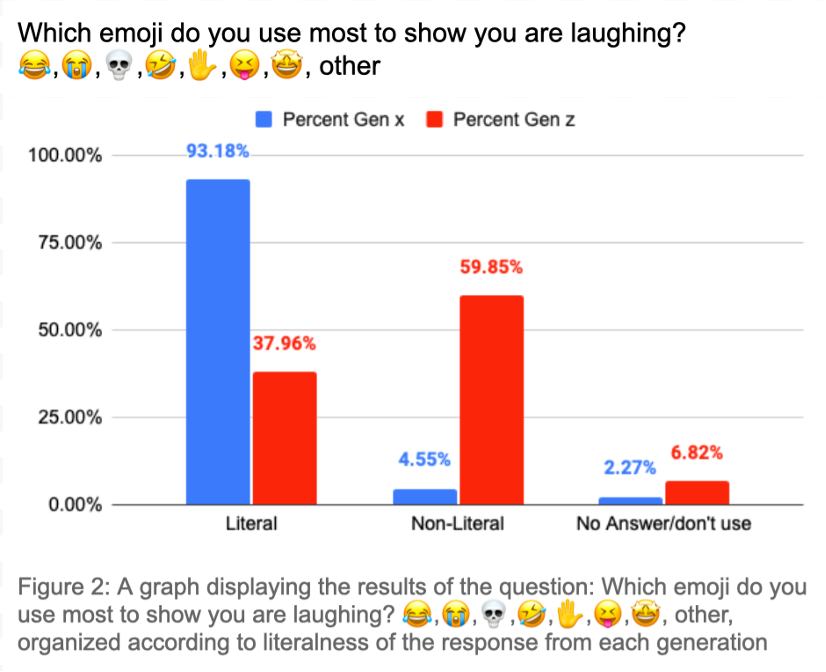

Beginning with our analysis of literal vs. non-literal use of markers, figure 2 presents a strong difference in Gen X and Gen Z’s preferences for literal and non-literal emojis.

The above graph illustrates a strong example of a general trend we found in our data: that overall, Gen X preferred to utilize emoji and other humor makers literally. In comparison, Gen Z showed a preference for less literal uses. Also, specifically for this question, within the categories of literal and non-literal, Gen X preferred a laughing emoji (😂) to show that they were laughing in 55% of their responses whereas Gen Z preferred a crying emoji (😭)–the exact opposite–to show that they were laughing in 42% of their responses. This was an even stronger non-literal response than expected suggesting a much higher degree of irony in Gen Z’s texting than in Gen X’s.

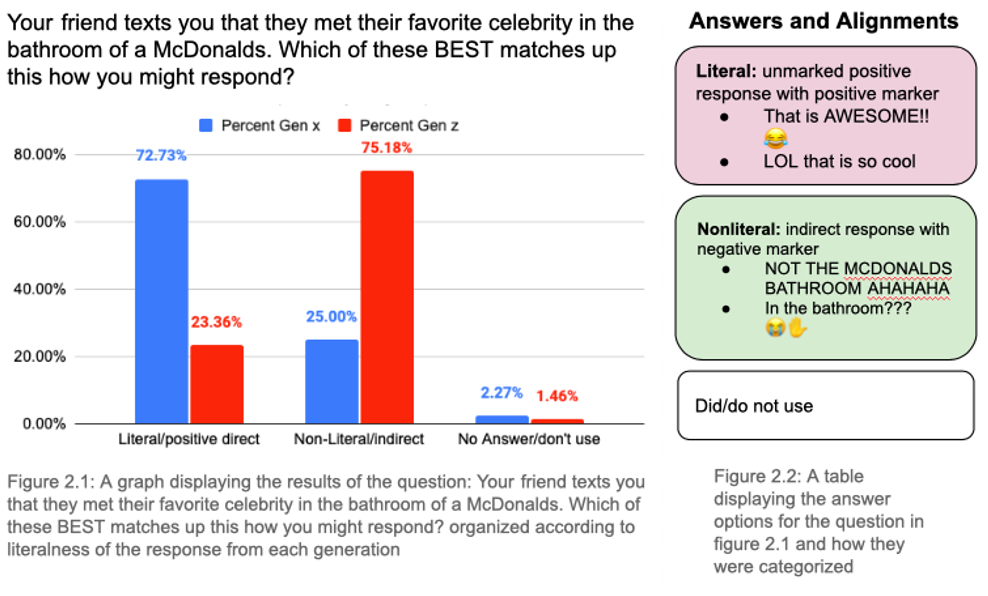

Moreover Figure 2.1 presents another strong case for Gen X’s preference for literal marker use and Gen Z’s preference for non-literal outside of just emojis. Figure 2.2 presents the response options as well as their categorization as either literal or non-literal.

Not only was Gen X’s preference for literal answers and Gen Z’s preference for non-literal answers illustrated in their selection of emojis but also in their preference for other answer types too. In the above example we took the unmarked and expected literal responses to the presented situation to be congratulatory, positive, and generally aligned with the topic of the context, whereas the non-literal responses demonstrate an indirect type of response by focusing on a non-topicalized part of the context (i.e. the bathroom). Again, we observed a strong preference from Gen X for a literal or positive response and a strong preference from Gen Z for a non-literal or indirect response.

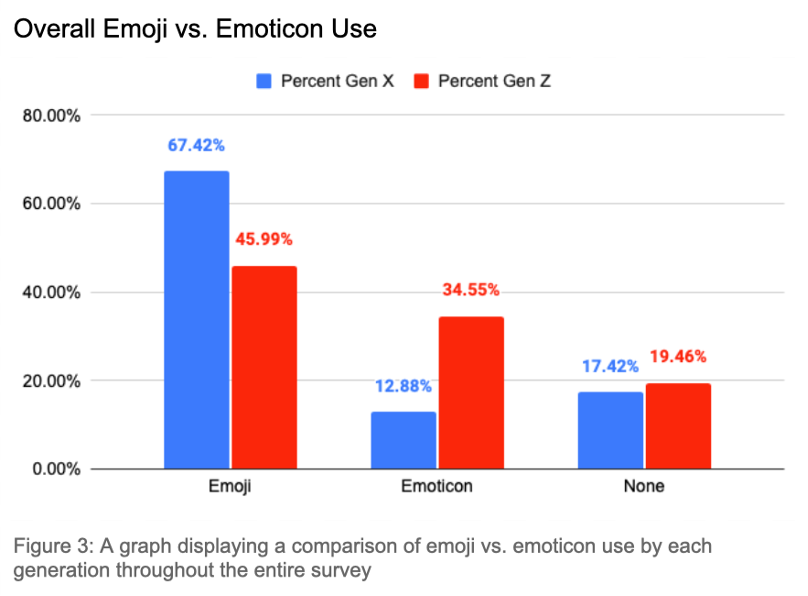

In addition to studying the differences in how humor markers were used to convey literal and non-literal meaning we also wanted to provide insight into the different variations in the types of markers commonly used. Generally, we expected to see a more diverse use of these markers and variations, not just emojis, in Gen Z’s texting, leading us to figure 3. Figure 3 illustrates the overall differences in emoji (😂,😩) and emoticon ( :(, 🙂 ) use according to generation.

We chose to study emoji vs. emoticon use specifically as we believed that there would be a strong difference between the generations. However, both Gen X and Gen Z tended to prefer emojis. Unexpectedly, Gen X overwhelmingly preferred to use emojis over emoticons. We had thought that due to their longer history and generally less ambiguous and more established static meaning that Gen X would favor emoticons (Bai et al., 2019). This was not the case. Interestingly too, Gen Z actually tended to use more emoticons than Gen X. This result however supports our belief that Gen Z would demonstrate a broader range of humor marker use, splitting their results more evenly between emoji and emoticon. This could also demonstrate that Gen Z is exhibiting more creativity or nuanced flexibility in how they use these markers and what they take them to mean.

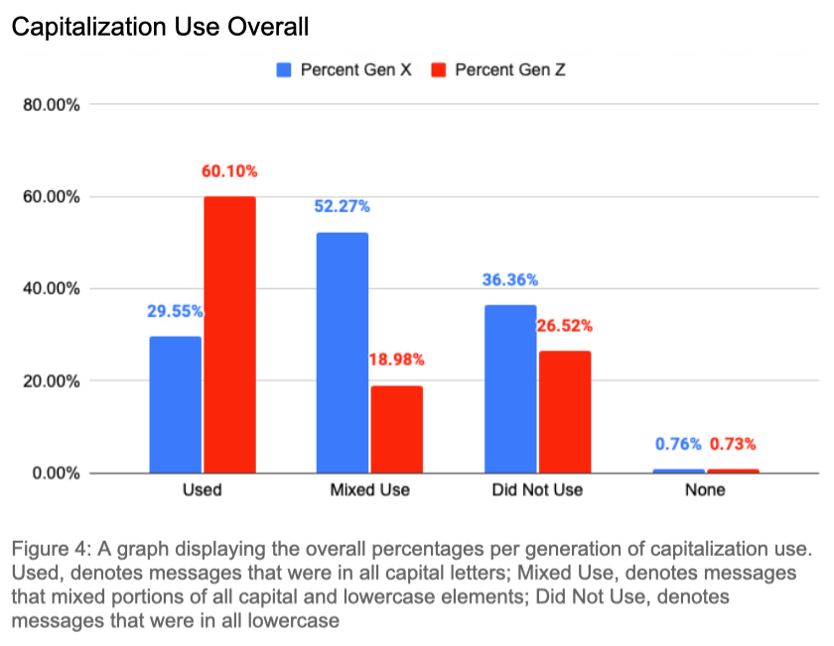

Next, we chose to study another variational marker, capitalization (OR SHOUTING). We chose to study capitalization in addition to emoji/emoticon differences as it is a unique action in texting that specifically denotes tone (McCulloch, 2019). Figure 4 below illustrates our comparison of capitalization use according to generation.

As shown above, Gen Z favored the use of capitalization while Gen X preferred messages that mixed capitalization and lowercase. This illustrates a stronger preference in Gen Z for using messages that convey a stronger or louder tone and demonstrates McWhorter’s idea of “written speech” in the younger generations (2017). Interestingly too, the younger generations’ relatively strong preference for “shouting” over text could indicate a recent change in what all-caps texting “means” and illustrate a higher level of comfort with the nuance of tone that all capitalized text creates. In comparison, Gen X may still interpret it as simply yelling at someone and therefore use it more sparingly. However, to corroborate those claims more testing would need to be conducted.

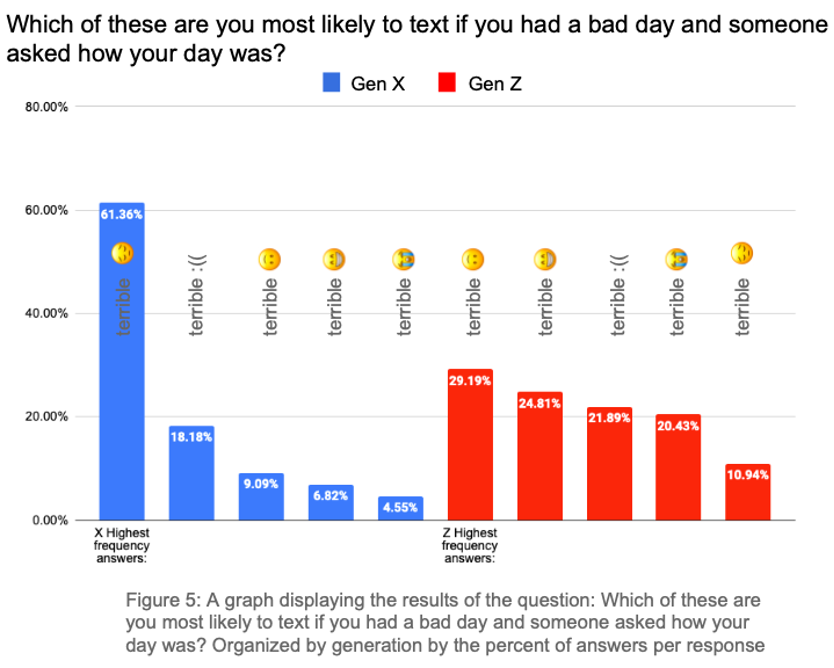

Finally, we got even more specific with our analyses–we categorized and analyzed the answers to each question on the survey to measure the frequency of each response per question for each generation. We did this to examine the specific texting behavior of the generations on a smaller, context-dependent scale. Figure 5 is a particularly interesting example that demonstrates the general trend in the generational behavior we observed.

We discovered, as in the above example, that Gen Z’s responses were more evenly spread out across the response options creating a much more dispersed answer graph (seen in red). Meanwhile, Gen X tended to answer more similarly to one another, strongly favoring one answer, ‘terrible 😔,’ as can be seen by the single tall blue bar. This pattern was relatively consistent across all of our data and was in line not only with our prediction that Gen Z would show a wider range of responses, but also with our prediction that Gen X would tend to use more literal responses. Moreover, another point to note in figure 5 particularly is that Gen X answered ‘terrible 😭’ 20.43% of the time, which in this context was interpreted as a literal use of a negative emoji. However, given our results in figure 1, this could also denote a more sarcastic or ironic tone. Such an analysis could also be in line with the other trend illustrated above as Gen Z showed a greater preference for answers that denote a less literal more ironic tone (terrible 🙃, terrible 😁).

Overall, our data demonstrated that Gen X tended to use emojis more literally and more consistently while Gen Z preferred to use them less literally and showed a wider range in their use. In terms of emoticons, both Gen X and Gen Z preferred emojis with Gen X showing a much stronger preference, and in cases of capitalization, Gen Z used messages in all caps much more than Gen X.

With all that said, we would like to address some possible confounds that could affect our data and analyses. Firstly, there was quite a disparity in the number of responses we received from each generation, heavily skewing toward Gen Z. This may have been because this survey was distributed by us (members of Gen Z), which also brings to light another possible issue: our own generational biases in both the analysis of the data and the creation of the survey. Additionally, this study’s construction as a multiple-choice survey poses the possibility that the choice of answers may have directed people’s responses. Moreover, we did not notice a significant effect of gender in our study. However, it could be a very interesting avenue to pursue in future research.

Discussion and Conclusion

As seen in our data analysis, we found that there is in fact a gap in the usage of humor markers between the two generations, which supported our initial predictions. More specifically, based on the overwhelming choice by Gen X to use literal meanings, it could be suggested that they tend to use them (especially emojis) at a surface level. Meanwhile, Gen Z’s varied usage of all four markers looks to be a bit more nuanced. Their choices reflect that they use ironic and non-literal meanings frequently in humorous contexts. The variation in their responses also suggests that each marker of humor could have its own unique function or meaning depending on the context. Such variety among Gen Z could be the result of their community of practice, which frequently takes part in internet culture and has therefore been able to develop their own unique understandings of humorous texts. It also reinforces McWhorter’s earlier suggestion that texting can involve more than words–it conveys natural human conversational gestures as well. Overall, it does therefore seem fair to say that there is more at play in Gen Z’s usage.

After conducting our study, we identified limitations in our methods that leave room for improvement. As mentioned earlier, the survey was created entirely by members of Gen Z. This could prove to be problematic because the response options are potentially more biased toward a typical Gen Z response and not adequately represent typical Gen X responses. Including the input of Gen X members could have created a more balanced selection of responses. Another less obvious limitation of our study is that we did not account for phone differences. We realize that the appearance of Android and iOS emojis differ and that this difference may procure different emotional responses and therefore be used in a different context than our survey initially accounted for.

So, what are the next steps? Our findings and conclusions tell us that there is definitely room for further research on intergenerational communication over text. Improving upon this study’s weaknesses and widening its scale could provide more insights into the big differences that lie between the text-language of Gen Z and Gen X. Some new topics of interest include: different attitudes towards the appearances of emojis (i.e. Android vs. iOS), the evolution and idiosyncrasies of Gen Z’s online language, and analyses of textual gaps that may occur on the basis of factors other than generation.

References:

Bai, Q., Dan, Q., Mu, Z., & Yang, M. (2019). A Systematic Review of Emoji: Current Research and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 2221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02221

Downs, H. (2019). Bridging the Gap: How the Generations Communicate. Concordia Journal of Communication Research, 6. https://doi.org/10.54416/SEZY7453

McCulloch, G. (2019). Because Internet. Penguin Adult HC/TR & Riverhead Books.

McWhorter, J. H. (2017). Words on the move: Why English won’t- and can’t- sit still (like, literally). Picador, Henry Holt and Company.

Sánchez-Moya, A. & Cruz-Moya, O. (2015). Whatsapp, Textese, and Moral Panics: Discourse Features and Habits Across Two Generations. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 173, pp. 300-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.069