Rae Cristal, Xin Liu, Jasmine Shao, Megan Ye

In their recent skit called “Gen Z Hospital,” SNL put on a show depicting the quirky lives of an average “zoomer”, filled with internet-related troubles. At one point, the distinctly white actress Heidi Gardner utters: “If he keeps leaving us on read, he’s gonna catch these hands on gang.” How did Gen Z lingo become so distinctly African American? One consequence of the internet age is the fast-spreading of linguistic style, forms and vernaculars, and African American Vernacular English (AAVE) seems to be one of the bigger targets of this phenomenon. A problem with this is that those who use AAVE do so inappropriately and with syntactic error. Taking a language that one does not speak and using it without appreciation and knowledge is the basis of appropriation, and many Gen Z speakers are engaging in this, often without realizing that, far more than just netspeak, the forms they are appropriating belong to a full-fledged community of speakers, with grammatical rules and cultural nuances.

Introduction and Background

Language has the power to reinforce harmful racial stereotypes and to determine how marginalized groups navigate American society. These groups whose speech differs from standardized English, specifically Black communities, are viewed as lacking grammar and speaking a less sophisticated language. Despite these misinformed perceptions of AAVE, many people on social media platforms, including Twitter and TikTok, appropriate AAVE words, phrases, and stylings, claiming these features as part of Internet speech. Such phenomenon continues, despite attempts from actual AAVE speakers to denounce its harmfulness:

Previous studies have researched AAVE appropriation by non-speakers on modern usage; although the analysis is limited, these papers provide a framework for why and how people with different genders and sexualities appropriate AAVE. Elaine Chun did a case study on an individual Korean-American male and his usage of AAVE “slang,” theorizing that he used it to index a hypermasculine persona and separate himself from European Americans (Chun, 2001). Due to the lack of material on the LGBTQ+ community’s utilization of AAVE, we speculated that LGBTQ+ members also used it to disassociate themselves from the white mainstream and to appear hip and nonconformist. To further explore AAVE and the personas it indexes, Ilbury argues that online spaces use the orthographic representations of AAVE to embody a “Sassy Queen” persona, which relies on stereotypes of Black women (Ilbury, 2020). Furthermore, non-Black speakers perform similar stereotype-based persona construction when they “borrow” African American Language to participate in hip hop or urban youth style. Through media representation and the marketability of “Black cool,” which is the culmination of all the desirable features of Blackness: trendiness, resilience, and eloquence, many young people and influencers use AAVE to index this stereotype based on white imagination (Roth Gordan et al., 2020). Corporate companies recognize the benefits of profiting from this perceived coolness, exploiting AAVE in their marketing campaigns and their partnerships with young influencers. These articles assist us in understanding the social and financial motivations of non-Black people’s usage of AAVE and why they take on specific personas.

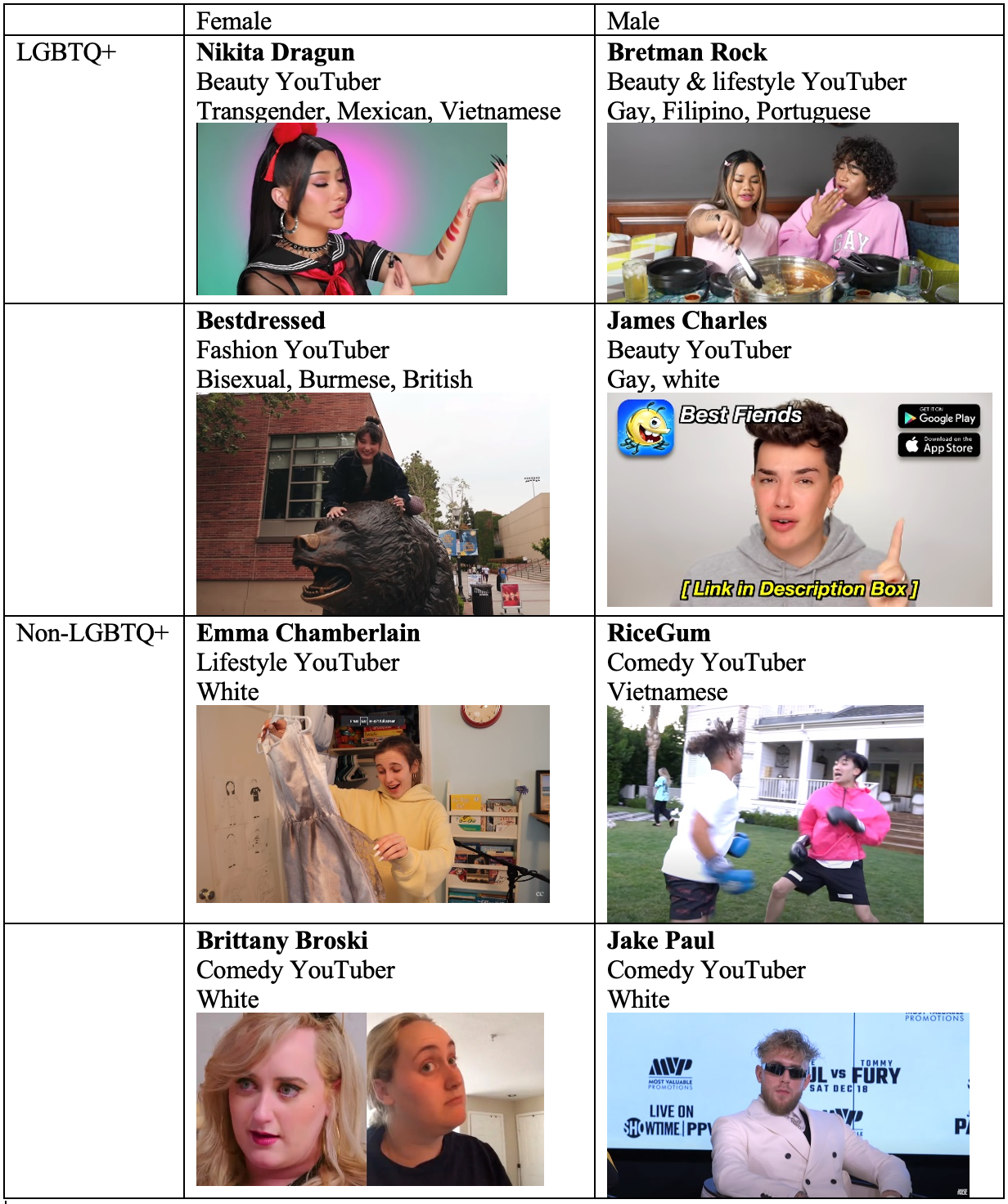

In light of the existing literature, we conducted a sociolinguistic study of non-Black Gen Z members by comparing their use of language in humorous and non-humourous contexts to identify how they utilize AAVE lexicon and accent to index a “funny” or “cool” persona. Also, due to the lack of research regarding the LGBTQ+ community’s usage of AAVE and the intersection of gender, our study analyzed the frequency of these linguistic features in social media influencers’ speech, particularly those who fit these categories. Overall, the usage of AAVE that became popularized through the Internet varies depending on gender, sexuality, and context. Methods We watched videos from eight non-Black, American, Gen Z influencers on YouTube and TikTok and recorded the instances in which they employed a lexical item or grammatical construction borrowed from AAVE.

Methods

We watched videos from eight non-Black, American, Gen Z influencers on YouTube and TikTok and recorded the instances in which they employed a lexical item or grammatical construction borrowed from AAVE. Our numerical analysis was based on a simple counting method. While it seems that counting a singular “instance” of grammar would be impossible in a traditional linguistic sense, this was possible because the influencers did not use any full grammatical constructions, but rather just one word in to imitate an AAVE grammatical style; e.g., “be” as in “[subject] be [verb]ing.” To determine what words and phrases were instances of AAVE, we referenced this guide, which was created by a group of Black people and non-black people of color with the intent to reduce appropriation in online communities. For words with multiple indexical meanings (such as “bitch” as a slur for women or “ain’t” as part of Southern dialect), we took their context into account to assess whether they were appropriated from AAVE. The eight influencers we examined were:

These influencers are a small group of the most popular internet users, and should not be considered a representative sample of all influencers of internet users. Rather, we intend for their selection to be a series of eight case studies examining intraspeaker differences in AAVE use. When watching the videos, we separated their content into two contexts for comparative purposes:

Non-humorous: Any segment of video or full video centered around the promotion of a product or service, such as a promotion of the influencer’s merch or a brand sponsorship

Humorous: Any other segment of video, because even those who are not solely comedy YouTubers are known to include humor in their content

We considered commercial content like sponsored segments, brand collaboration videos, and formal interviews non-humorous because influencers tend to act “professional” and remove the informal, humorous aspects of their speech in promotional contexts. If their use of AAVE is significantly higher in humorous contexts, we can assume that their use of AAVE is tied to the indexing of humor, rather than a reflection of their natural speech variety. For the LGBTQ+ speakers, usage of AAVE mostly was characterized by borrowed lexical terms that indexed sass and cheekiness. Here is an example of how we recorded and examined AAVE use. This is transcribed from a Nikita Dragun video titled “REACTING TO MY BOY VIDEOS!!”:

● [0:58] “tea” (used to describe drama and not the drink) ● [2:13] “clock it the house honey,” ● [3:08] “shook,” ● [7:08] “unclockable” (derived from clock), ● [7:31] “thick” (referring to a person’s figure and not literal thickness). ● Total: 5 in 10 min

This is transcribed from a Bretman Rock video titled “Hugging for the first time? Catching up with my Sister”:

● [01:11-01:24] I just know they’re bomb though. I just know they’re bomb_ (bomb meaning cool/great, extremely positive connotations) we have two dishes of broth--uhm; they’re both seafood broth one is spicy and one is mild and I believe this one is kimchi. We have udon Chinese CABbage enoki mushrooms up. In. this. BITCH. (imitating AAVE grammatical structures) ● [01:57-2:17] SIS. (used to refer to friends/peers, not literally speaker’s sister, although in this case she is) whatchu been up to? (grammatical structures) PERIOD! (used to mean “and that’s that,” a marker of finality—online may be spelled “periodt”) and we gon keep doing you. (grammatical structure) Purr. (used to express approval/satisfaction) um YEAH BITCH you’re twenty ONE we can have drinking videos now. Period. ● [02:55-03:02] she got FUCKT! (lexical feature, -t suffix replacing -ed) UP!Perio;d that’s all that matters_ NEW age; new DICK. purr! ● [03:37-03:39] this bitch been telling everybody (using the habitual be, e.g. is, are, am) ● [04:15-04:17] yeah you don’t deserve. Period. ● [04:34-04:41] the thing IS she ain’t even done like celebrating her birthday (grammatical structure) yet what the <<slurred, quick>fuck’re you gonna do in LA bitch this bitch is gonna stay in my apartment ● [04:54-05:01] bitch I always be telling you tips and tricks but you don’t even listen so it’s like you know what some people just wants to learn on their own and that’s fine ● Total: 14 instances in 5 minutes ● Overall, Bretman Rock’s usage tends toward leaning heavily on the “sassy Black woman” stereotype as a persona. He overutilizes—at times randomly and incorrectly— “periodt” and more commonly puts on a persona when he is interacting with women and LGBTQ+ individuals.

As for the Non-LGBTQ+ speakers, their usage of AAVE varied. Males usually used borrowed grammatical forms and lexical terms. Here’s an excerpt from Ricegum’s video titled “Meeting My Online Crush For The First Time!”:

● [00:43] - [0:45] Yo so listen, but you can’t even be sliding into dms in Tik Toks (invariant be usage)

● [00:58] - [01:02] She’s finna just appear. It’s finna just be magic (borrowed term)

● [05:33] - [05:35] But you don’t be hittin’ those other dudes back?

● Overall, Ricegum ports an overall blaccent and overutilized penultimate consonant deletion.

● Total: 10 instances in 8 minutes

For female users, their usage of AAVE varied based on their humor. In particular, one of the influencers showed signs of self-awareness and utilizes it ironically. On the other hand, Brittany Broski uses lexicon to index a sassy persona. Here’s an example from Brittany’s video titled

“Deep Diving My Angry 2013 Tumbler”:

● [0:52]-[0:58] This whole idea of stan culture on Twitter really was like the thing at the time. If you didn’t have a stan account

● [1:00]-[1:04] So this was my stan account in high school because I never had a One Direction Twitter

● [3:50]-[3:54] Oh my god I loved this bitch I ate this shit up

● [4:57]-[5:00] I genuinely was like real mean don’t wear pink, swag

● [8:44]-[8:48] Another boyfriend Harry post wow period, period

● Total: 11 instances in 11 minutes

Results and Analysis

Discussion and Conclusions

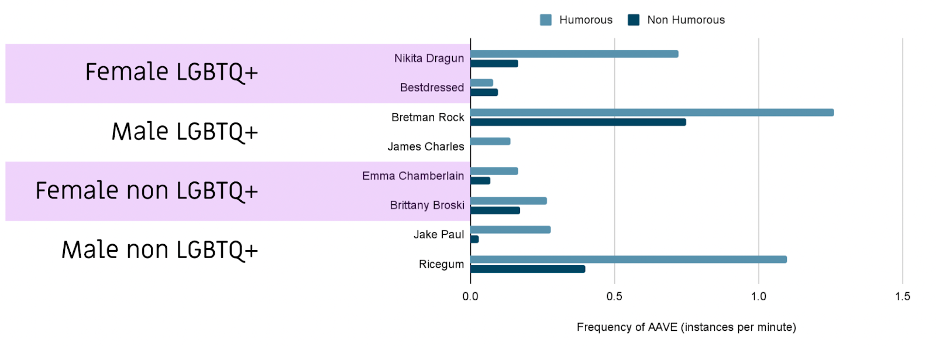

Most of the influencers examined here have significant differences (see Figure 1) in AAVE usage between humorous and non-humorous contexts, which confirms our hypothesis that influencers choose to change their styles for social benefits. Sexuality and gender expression also appear to have an effect on the instances of AAVE usage. LGBTQ+ influencers, especially men, tended to use AAVE to index a “sassy” persona, based on the stereotype of the “sassy Black woman.” On the other hand, non-LGBTQ+ men tended to use AAVE to index a “tough” or “masculine” persona, based on the cultural masculinization of Black people. Influencers use AAVE to index a funny, sassy, or edgy persona because of cultural stereotypes around Black people and their language. These stereotypes date back to minstrelsy in which Black people were treated as entertainment tools for white people. Today, this derogatory cultural lineage lives on in the appropriation of Black people’s language as an entertainment tool for non-Black people. These public figures’ influence leads to further spread of these speech patterns, indexed in these ways, without acknowledgement of the source and the price paid by Black people who have native fluency in AAVE. Influencers of this caliber have great potential to impact their audience, and carelessly using AAVE without acknowledging its origins will propagate the idea that AAVE is simply netspeak, which leads to the broader population of Non-Black Gen Z speakers using incorrect forms, or completely disregarding the cultural implications of knowing the language:

People tend to feel inappropriate when they incorrectly use grammar in a language they do not speak or are just beginning to learn. However, that does not appear to be the case for when non-speakers of AAVE misuse its grammar. This further contributes to the myth that AAVE is not, in fact, seen as a legitimate vernacular language of its own, and helps fuel extreme cases where people actively discredit AAVE entirely:

It is not inherently bad that the internet is shortening gaps between different cultures and as a consequence, languages. However it is the due diligence of every responsible internet user to ensure that they are not just passively absorbing all the information that is available to them and mindlessly replicating them. When the majority uses (and misuses) the language spoken by a minority only to express particular ideas, they, at best, contribute to the viewpoint that the variant is not legitimate, and at worst, reaffirm the racist ideologies that exist to oppress Black people (see Figure 5). When Black people use AAVE, people assume that they don’t know Standard English. However, when non-Black people use AAVE, people assume that it’s a choice—one to appeal to humor. These double standards further propagate racism towards Black people and devaluation of African American Vernacular.

References

Chun, E. W. (2001). The Construction of White, Black, and Korean American Identities through African American Vernacular English. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 11(1), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.2001.11.1.52

Davis, Chloe. “The Language of Ballroom.” The Gay & Lesbian Review, 9 Mar. 2021, https://glreview.org/the-language-of-ballroom/

Eberhardt, M., & Freeman, K. (2015). ‘First things first, I’m the realest’: Linguistic appropriation, white privilege, and the hip-hop persona of Iggy Azalea. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 19(3), 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12128

Ilbury, C. (2020). “Sassy Queens”: Stylistic orthographic variation in Twitter and the enregisterment of AAVE. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 24(2), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12366

Roth-Gordon, J., Harris, J., & Zamora, S. (2020). Producing white comfort through “corporate cool”: Linguistic appropriation, social media, and @BrandsSayingBae. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2020(265), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2020-2105