Kayla Cardoso, Van Hofmaister, Jamie Jiang, Clarissa Sie, Rainey Williams

In 2016 a 1979 interview with Jodie Foster resurfaced on the internet and instantly took hold in the meme community. When asked about a potential boyfriend, Jodie smirks, licks her lips, and raises her eyebrows in a manner that gives the impression she knows something that her interviewer does not. The label [gay silence] was given to this instance and it has become a part of gay culture and the LGBT community as an identifying feature of closeted individuals. With this in mind, our study takes a sociolinguistic approach to analyzing and examining the idea of a sapphic/lesbian code. Coded sapphic speech is not well studied in sociolinguistics, and while the community itself is able to identify markers of such, there has been little to no substantial research on identifying features present in sapphic language. In analyzing the speech and body language of sapphic celebrities, we seek to provide evidence and tools to identify linguistic markers.

Introduction and Background

If you’re a particularly online or memelord-y queer person, you might have seen the “gay silence” meme by now. A young Jodie Foster, who now publicly identifies as lesbian, stares off-camera at her interviewer with a slight knowing smile and a strained look in her eyes. The subtitles characterize her contribution to the conversation as “gay silence.”

The image comes from a 1979 interview with 17-year-old Jodie Foster on the Macneil/Lehrer Report. Clips of the interview resurfaced a couple years ago and caught the attention of the sapphic community (“sapphic” is an inclusive term referring to any person, woman or otherwise, who identifies as lesbian). In the clip, Foster answers awkward questions about the kind of boyfriend she would like and the qualities in actresses that “turns” her on.

Foster is generally seen as early lesbian “icon”. One YouTube comment about the interview jokes: “Jodie Foster founded Lesbianism. She’s like the final boss”. Another viewer writes: “the gay energy in this is immaculate.” Most viewers point out Foster’s subtle subversion of the heternormative questions. Another commenter points out how young Foster’s mannerisms match contemporary codes of lesbianism – “Every mannerism she has is now lesbian code. Funny, right? (Way of sitting, way of taking the cup of tea, way of talking).”

Coded sapphic speech is not well studied in sociolinguistics. While the community itself is able to identify lesbian markers, as demonstrated by the commenters above, there has been very little empirical research on those markers in language. One commentary by April Jackson published in a feminist journal called “Bringing Lesbian Language Out of the Closet” claims lesbians do not have a collective public language. Nothing in the literature we found could support this claim, but the literature pool is already small. Most studies on sapphic speech are conducted on lesbian acoustic features under the stereotype-driven fallacy that gay women are the acoustic mirror of gay men, otherwise known as “Gender Inversion Theory” (Kachel 2017).

Our study aims to fill this gap with a thorough study of “out” sapphic speech. Specifically, we provide two case studies, lesbian and sapphic icons Jodie Foster and Kristen Stewart, characterizing the way sapphic celebrities speak about love, family, and sexuality before and after coming out.

Methods and Transcription Notation

Our hypothesis was that these women will behave differently depending on if they know the interviewer – and by extension, the greater audience – is aware of their identity or not.

With particular interest given to observing lesbian speech in environments where responses are elicited by another individual in regard to matters of romance, personality, and private life, we performed conversation analysis on queer women Jodie Foster and Kristen Stewart from the existing canon of interviews in the public record. We analyzed interviews on a scale of “outness” – before publicly coming out, in more “out” settings, and after publicly coming out – in order to draw comparisons and see if different aspects of their employed speech changed after they perceived members of their audience as aware of their identity.

Using conversation analytic methods, that data was examined for prosodic changes, i.e. hesitations, silences, breathiness, emphasis, and volume fluctuations. Particular attention was paid to: potential pauses[1] between utterances (the question and the intended response), employment of gendered versus gender-neutral words, and perhaps instances where the subject avoids the topic altogether. Furthermore, although more paralinguistic than overtly linguistic in nature, physical movements and posturing of the body in response to different questions allowed further insight into an interviewee’s response. Comparing this with later interviews where a given celebrity’s identity is public knowledge gave us an idea of whether or not these linguistic and paralinguistic choices were simply personality quirks.

[1] In conversational analysis, a pause conveys meaning. The amount of time after an utterance is spoken may reflect different attitudes in a speaker. Such length after a pause can be interpreted as a few things, including hesitancy, disagreement, lack of interest, or that the speaker is having a hard time thinking of how to respond. We will be actively taking note of the length of any pauses within interviews in order to gauge how the speaker might be feeling in response to some interview questions.

Special attention was given to the interviewer’s demeanor, attitude, and in what context the celebrity was being asked these questions, as well as the content of the questions being asked, and whether those questions became more invasive once an interviewer knows they are asking someone who is lesbian. We tested for the possibility that our subjects were simply exhibiting discomfort while answering personal romantic questions, no matter their sexuality. As a method of control, the study includes conversation analysis on Brooke Shields and Amanda Seyfried; two heterosexual women who are contemporaries with Jodie Foster and Kristen Stewart respectively.

Transcription Notation:

- [Overlap Bracket: Left brackets mark the point at which the current talk is overlapped by other talk.

- Stressed Syllables: Underlined letters are used to indicate an emphasis on a word.

- ° Low Volume: A degree sign indicates that talk it precedes is low in volume

- Silence: Numbers in parentheses mark silences in seconds and tenths of seconds

- Increased Volume: Upper case indicates increased volume.

- Breathiness: An (h) indicates plosive aspiration, which could result from events such as breathiness, laugher, or crying

- Noticeable Pauses: A period between two parentheses is used to indicate (short) pauses.

Results and Analysis

Brooke Shields

In order to have a point of comparison to Jodie Foster (one might say, hetero to Jodi’s homo), we chose to do conversational analysis on acclaimed actor and model Brooke Sheilds. Shields has been in the public eye as a famous figure her entire life, given her assimilation into the acting and model industry from a very young age (Shields was doing model jobs as an infant). Shields was also considered a very attractive individual, and given the subject matter she starred in (one example being the controversial–and in this writer’s opinion, very gross–film “Pretty Baby”) became a “sex symbol” in her teenage years.

This mindset of the public in regard to Shields led to her interviews being riddled with topics circulating towards: sex, men, crushes, boys, and other sexually or romantically charged vocabulary.

Given the frequency of such words as well, it provides viewers a good point of reference to how Shields would respond to questions that were deemed more harmless (crushes) to those that are more inappropriate (sex). For our study in particular, having interviews where the interviewer had the pre-existing mindset that Shields is someone her fans “desired” is a good control for Foster’s behavior. This way, we can look into similarities and differences with regards to how invasive a question is without any distinction made between sexuality. Sometimes the things people are asked, point blank, make them uncomfortable.

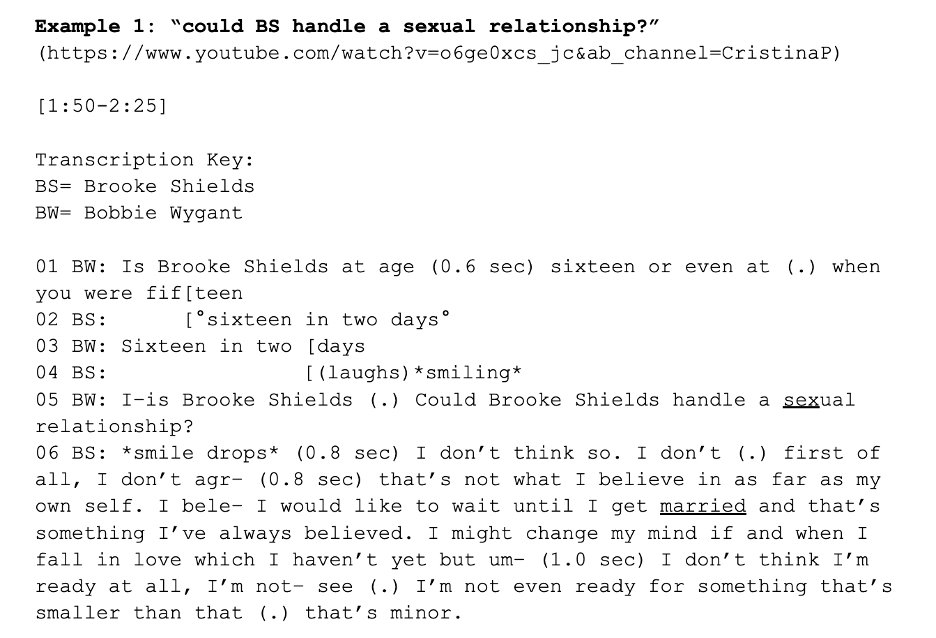

The first conversational analysis performed was on an interview in 1981 by the interviewer Bobbie Wygant (who also interviewed Foster two years prior). In the interview Wygant asked Shields many questions about sex, rather than the plot of the film she was in at the time. Wygant asked things like whether or not she thought that young girls are able to have sexual relationships, later leading to her question to Sheilds, herself, about whether she could handle a sexual relationship or not. Shields at the time was 15 and seated between two of her adult male co-stars in the film “Endless Love”.

Some of the aspects of Shields’ response that were particularly noteworthy was her use of laughter towards the beginning of the interview, as well as the significant pauses she evokes after Wygant asks her the invasive question. Shields also stutters slightly, and has more pauses as she gathers her thoughts together in order to construct what people in the comments of the interview called “classy” or “graceful” despite the question’s probing content . Overall, the biggest instance of perceived discomfort for Shields’ responses to questions was found in this interview where the topic itself was something deeply personal and invasive to ask anyone.

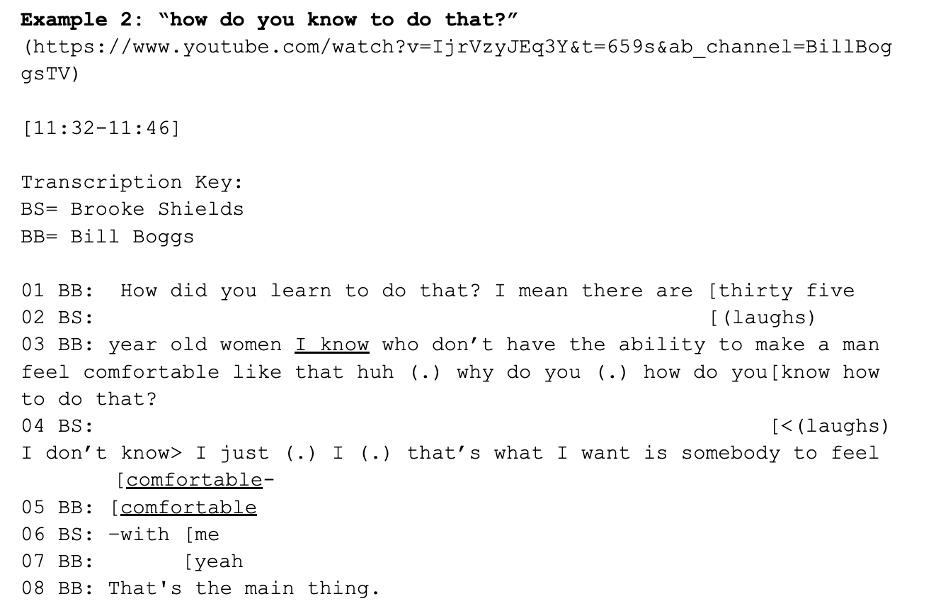

The second interview of import was conducted by Bill Boggs around a similar time in Shields’ life. Contrary to the Wygant interview, Boggs interview doesn’t explicitly ask Shields about sexual relationships, some of it is implied however. At one point in the interview Boggs asks Shields about her ability to make men feel “comfortable” with her. He even compares her ability to “thirty five year old women” he knows who aren’t capable of the same thing. Such a question, to an observer, seems off, especially considering the comparison between fully grown adult women and Shields, who was only a teenager at the time.

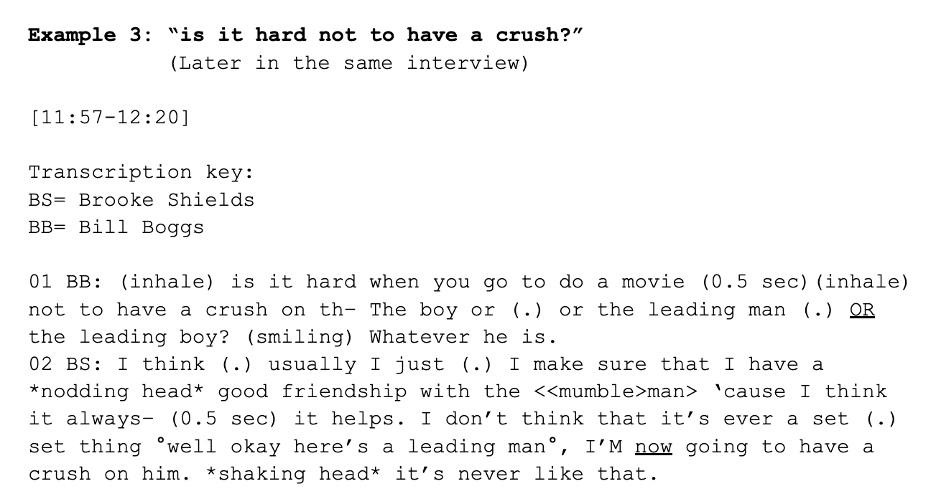

Similar to the previous interview there is evidence that Shields uses laughter as a response to a question that has some degree of romantically charged backing. In the later part of the interview Boggs asks Shields about the difficulty of not getting a crush on her male counterpart in a film.

Similar to the previous interview there is evidence that Shields uses laughter as a response to a question that has some degree of romantically charged backing. In the later part of the interview Boggs asks Shields about the difficulty of not getting a crush on her male counterpart in a film.

Shields doesn’t hesitate to use masculine pronouns to refer to the recipient of her hypothetical crush, and although she does include a pause, it is more similar to her gathering her thoughts than being read as uncomfortable as it was in the first interview example (comparing a 0.5 second pause to the 0.8 or solid 1.0 seconds in the interview with Wygant). The only instance in which there is some aspect of her response that could portray uncomfort is when she mumbles the word “man,” however this is much more likely to be attributed to the fact that she was still a teenager at the time and her co-stars were more often than not older than her by a decently large margin.

Shields also has open body language in her interviews, where she smiles back at the interviewer, nods or shakes her head, and most noticeably laughs as a response to various questions.

Jodie Foster

Results from conversational analysis on Jodie Foster stood out from conclusions we drew on her heterosexual contemporary, Brooke Shields, in four ways:

(1) Foster used “the gay silence” when closeted;

(2) Foster used gender-nonspecific terms when closeted;

(3) Foster played with gender roles more often in a more “out” setting than in a closeted one;

(4) Foster was a more supportive and intimate conversation partner in an “out” setting.

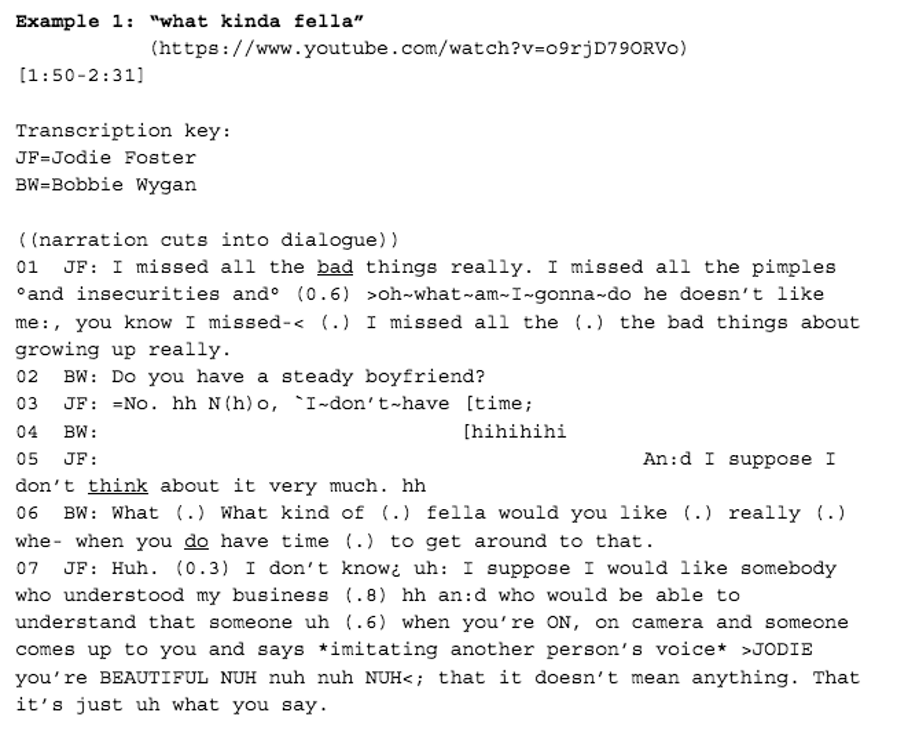

In the interviews we analyzed discussing romance and sexuality, Shields responds to interviewers using laughter 50% of the time. By contrast, Foster used “the gay silence”. In a 1979 interview with Bobbie Wygan, Foster responded to heteronormative questions about her love life with several pregnant pauses.

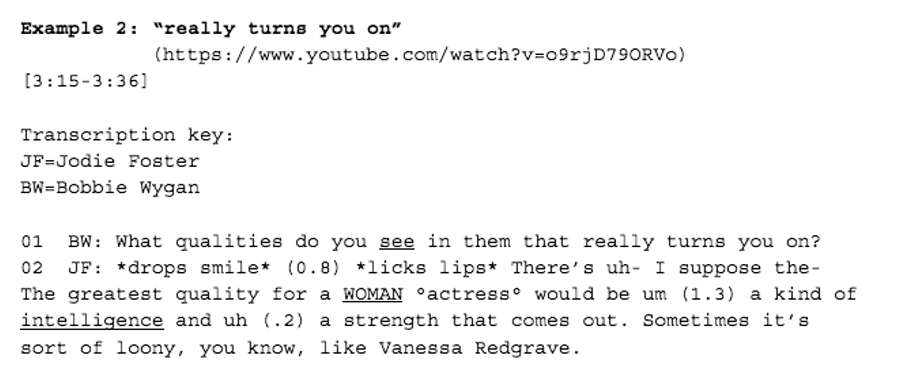

Foster’s silences came to an average of 0.49 seconds overall, twice using a 0.8-second silence during clips from the 1979 interview. Her longest silence occurred after the interviewer asked an awkwardly phrased question – what qualities in a female actress “turns” Foster “on” – a total of 1.3 seconds. This is the longest silence of any interviewed subject in our research.

Foster also used gender non-specific terms when closeted and avoided giving pronouns to potential romantic partners. In Example 1, Foster expresses a desire to date “somebody who understood my business” when the interviewer specifically asked about a “fella.”

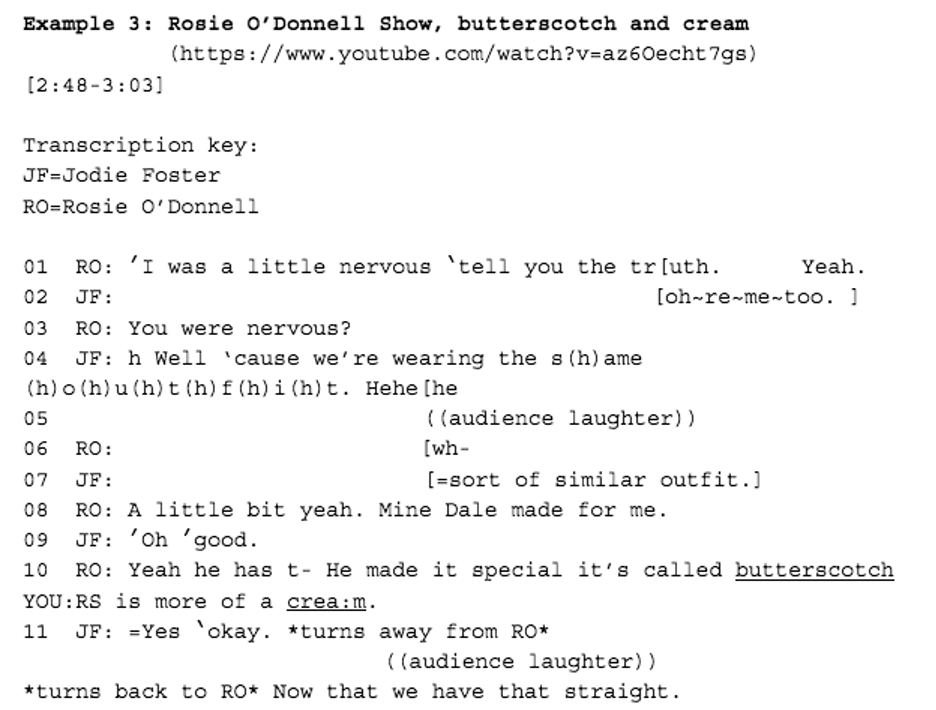

We classified an interview with fellow closeted lesbian Rosie O’Donnell as a slightly more “out” setting than other interviews, even though the public was still largely unaware of her sexuality. The brash show host with a deliberately comedic style, O’Donnell played with gendered language and perceived gender roles during her conversation with Foster, prompting the same subversive gendered language in Foster.

Robin Lakoff (1973) hypothesized that “women’s language” (WL) incorporated more color vocabulary than non-WL. The performance and nonperformance of WL in this interview highlights how queer women subvert gender in liminal “out” spaces. In Example 3, O’Donnell prompts audience laughter by drawing an exaggerated distinction between “butterscotch” and “cream” clothing. She appropriates highly feminine language (pointing out shades of difference in clothing colors) while highlighting her less prestigious New York accent (perceived as “rough” and “lower class” and therefore masculine). The joke results in a clash between feminine language and masculine presentation.

Robin Lakoff (1973) hypothesized that “women’s language” (WL) incorporated more color vocabulary than non-WL. The performance and nonperformance of WL in this interview highlights how queer women subvert gender in liminal “out” spaces. In Example 3, O’Donnell prompts audience laughter by drawing an exaggerated distinction between “butterscotch” and “cream” clothing. She appropriates highly feminine language (pointing out shades of difference in clothing colors) while highlighting her less prestigious New York accent (perceived as “rough” and “lower class” and therefore masculine). The joke results in a clash between feminine language and masculine presentation.

Foster responds by rejecting the feminine language and instead adopting a masculine disinterest in the color difference. She turns away from O’Donnell to look at the audience before ironically saying, “now that we have that straight.” This presents another clash in gender presentation and therefore subversion of gendered language.

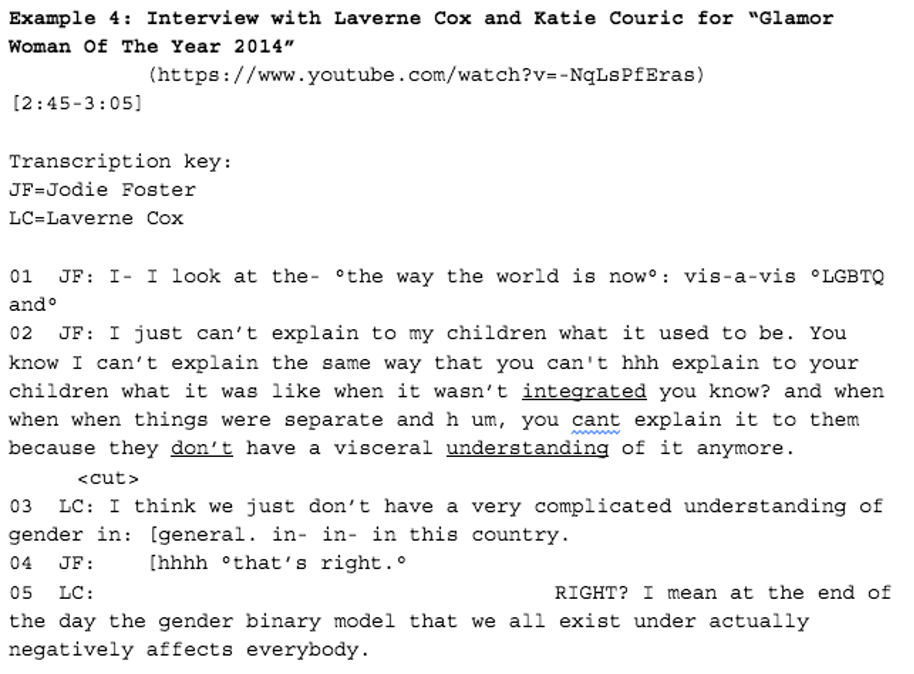

We analyzed another “out” setting in which Foster comfortably indexed her queer identity in an interview. In 2014, Foster presented the “Glamour Woman Of The Year” prize to transgender icon and friend Laverne Cox. This was only a year after Foster publicly “came out” in the public sphere. Foster and Cox’s interview with Katie Couric after the awards ceremony displays Foster’s intimacy and vulnerability while speaking about her family and the state of queer liberation in 2014.

Foster speaks quietly and slowly, with heavy and personal emphasis, while speaking about the progression of LGBTQIA+ liberation. In the next cut, Foster indexes her intimate friendship with Cox as well as her solidarity with Cox’s experiences through supportive interruption (Tannen, 1993). Foster cuts in with a positive response (chuckling in line 04) and affirms Cox’s experiences. Cox, in turn, acknowledges the support in line 05.

Contrast this interaction with a far more disastrous interview from 2007 in which a straight male interviewer made an inappropriate joke about Foster’s lesbianism. In that interview, we found Foster speaking in extremely high pitch, laughing, stuttering, and backing away from engaging with her interviewer on several topics of conversation. In the next appearance Foster made on the show, the interviewer joked that Foster didn’t like him; perhaps alluding to her uncomfortable retreat from their last interview.

Amanda Seyfried

Amanda Seyfried was chosen as Kristen Stewart’s heterosexual counterpart because of her similar exposure to fame. Amanda’s breakout roles in Mean Girls (2004) and Mama Mia (2008) lead to a surge of interviews in the young actress’s life, just as Stewart’s breakout role in Twilight (2008) spawned a plethora of interviews. Seyfried’s dating activity has always been accessible to the public, whether that be through social media posts from the actress herself or public interviews. In our chosen interview Seyfried is being interviewed by Ellen on daytime television, with the topic of conversation being Seyfried’s recent vacation with then boyfriend Justin.

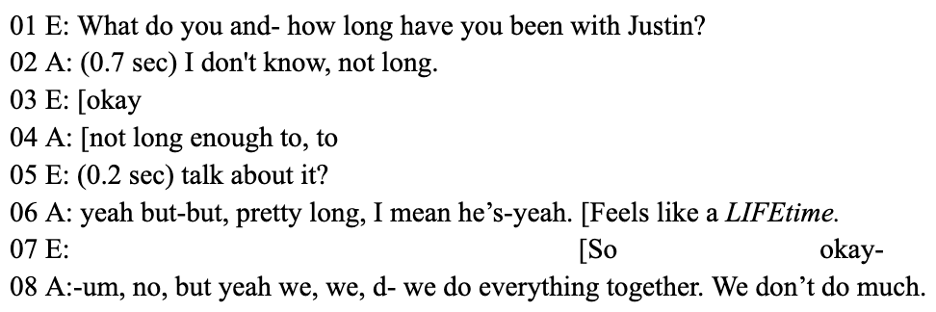

After Ellen’s initial question of how long she has been with Justin, Seyfried pauses and is unsure of her answer. She continues to build on her thoughts and answers Ellen’s question fully with sincerity across lines 04-08. When Seyfried says in line 06 that it feels like a LIFEtime, she make a contrast between the short time they’ve been together and the potential romantic exaggeration of saying “lifetime,” making the line come out as almost a mocking joke, but her follow-up with sincerity, saying they “do everything together” in line 08 confirms the truthful tone of her latter statement.

Kristen Stewart

Kristen Stewart is an actress who has stated that she has never felt truly “closeted” – in the sense that she never attempted to hide her attraction to women, and even before any official statements about her sexuality, or public appearances with female/nonbinary partners, she has shown obvious interest in women. When analyzing her speech, it’s important to keep this in mind, because it may inform interpretations of her answers to certain questions.

Stewart is an interesting subject to study, particularly because of her strong presence in the public eye as a romantic lead in Twilight. Conveniently, during filming of the Twilight series, she also appears as Joan Jett in The Runaways, where she has an on-screen romance with female co-star, Dakota Fanning. Comparing her reactions to prying questions in context of both Twilight and The Runaways gives us a way of judging her comfort level without confounding variables such as age or level of fame, since they take place in the same timeframe.

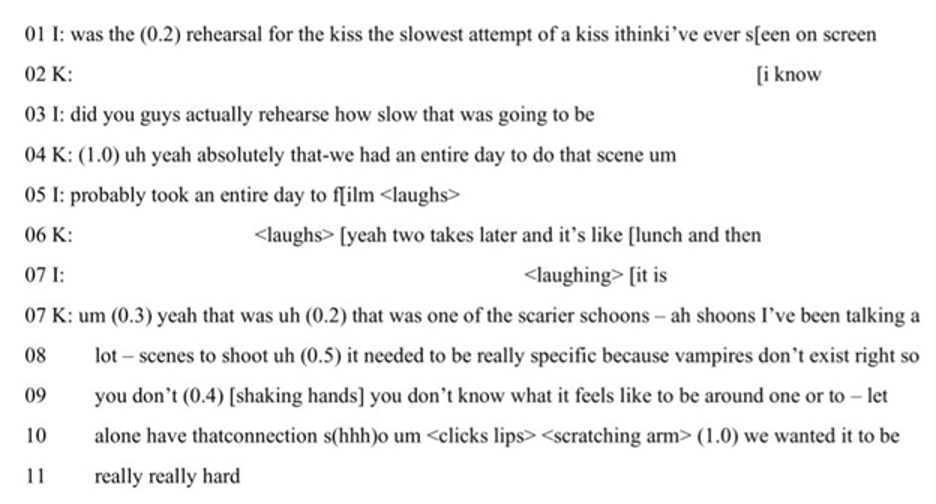

Stewart is a person who has been classified as shy, guarded, or introverted, mostly in response to questions about her romantic life, and such discomfort can be seen in several interviews where an interviewer will ask her about her relationship with Twilight co-star, Robert Pattinson. In one interview, an interviewer questions Kristen on filming a particular kissing scene with Pattinson.

Previously fluid and casual, Stewart begins to stutter, use filler words, and make speech errors, as well as take significant pauses in her speech. Most notably, she also avoids the question entirely, choosing instead to mark on the filming process and vampirism as a concept, rather than her chemistry with Pattinson. Similar reactions can be found in several other interviews on the same subject, where solicitations of romantic involvement with Pattinson are met with stuttering and subject avoidance. In one interview with Oprah, the host even remarks on Stewart’s publicly-known coyness on the subject, directing the question to Pattinson himself only for him to similarly dodge the question, albeit in a more humorous and comfortable way.

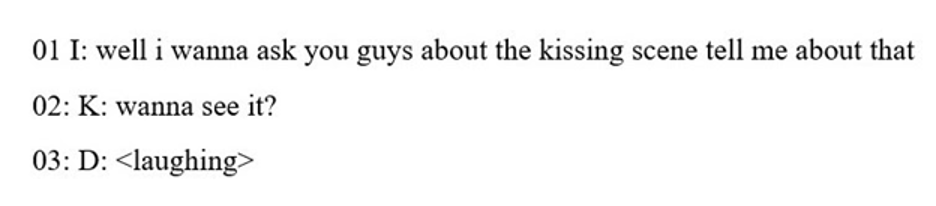

Alternatively, Stewart’s shyness did not seem to extend with her onscreen romance with Fanning, and in interviews with similar questioning, responded with confidence, humor, and ease.

Rather than avoid the subject, she leans into it and encourages more conversation. When questioned about the “best kisser” in the context of her Twilight love triangle, she responds with “Dakota” in several different instances. This lack of trepidation is consistent among a number of interviews, with and without Fanning next to her.

Later in her life, Stewart began making her romantic involvement with women more public, and announced an engagement with her fiancée, Dylan Meyer. The same ease, confidence, and positive language can be observed when she talks about Meyer in an interview with Jimmy Fallon.

She no longer stutters, she uses objectively positive language discussing her partner, and has an open and relaxed posture. Additionally, Kristen in line 02 begins to laugh as she says “thanks” causing a break in her voice. This is her first observed initiation of laughter, possibly displaying increased confidence (compared to previous interviews where she only mimics laughter after someone else has initiated it).

Discussion + Conclusions

This study rebukes previous literature that claims sapphic people do not index their identities in their speech or that sapphic mannerisms should be mirrored counterparts of gay mannerisms. Our study of famous sapphic celebrities and “icons”, juxtaposed with their heterosexual contemporaries, show us that those sapphic individuals speak very differently in “out” settings than in “closeted” settings (whether they are completely closeted, in the presence of other sapphic people without being out to a larger audience, or completely out and discussing matters of love and sexuality). They exhibited a marked difference in comfort level, gender role performance or subversion, and positive or more intimate interlocutory behaviors.

Our results show that Foster in “out” settings, unlike her contemporary Shields, tends to subvert gender roles more often in interviews. Additionally, “out” Foster acts more supportive towards LGBTQIA+ interlocutors than towards heterosexual interlocutors. “Out” Foster speaks personally and intimately about matters of queer liberation, whereas closeted Foster becomes greatly uncomfortable and withdrawn when confronted with the question of her sexuality.

Additionally, unlike Shields (who used laughter as a frequent form of response), closeted Foster tends to display discomfort about probing personal questions with the “gay silence,” a knowing silence that avoids an admission of homosexuality but also tends not to display overt heterosexual enthusiasm.

Amanda Seyfried’s playful but overall sincere comments on her current partner can be compared to a closeted Kristen Stewart’s reaction to questions about heterosexual romantic scenes with long silences and avoidant interlocutory behaviors. Contrasting these behaviors with “out” Kristen Stewart’s speech, we find a marked positivity and confidence, given her newfound laughter initiation and active gesturing (“knocking” it out of the park) when speaking on subjects engaging in her sexuality.

Our research adds to Kachel 2017’s work by further providing evidence that Sapphic speech cannot be indexed in the binary of heterosexual women vs. homosexual women. Rather, our results show that the psychological states and conscious identifications of these individuals (awareness of interlocutors’ sexuality, awareness of audience’s knowledge about their sexuality, comfort level with indexing non-normative gender or sexuality identities) are much more important factors in whether or not sapphic speech surfaces.

This research also marks one of the first uses of CA in individual case studies to examine the use of Sapphic speech. We recommend that further research follow our direction of case studies and examine larger corpuses of data from one Sapphic subject in “out” and closeted settings to corroborate our findings about gender performance, “gay silence”, and comfort level. Additionally, we recommend further conversation analysis studies performed on sapphic individuals’ conversations within the sapphic community and compare those results with sapphic-heterosexual conversations. Finally, we recommend more robust research into the sapphic community’s online language to better understand how sapphic speech may have developed in recent years.

Additional References

We have included an assortment of different links below used to draw conclusions and make connections between our research topic and other sources. The type of links vary from articles from pop culture media, to youtube links of different interviews conducted with celebrities.

Vice – Lesbian Culture Has Had a Major Update

(an article briefing “additions” to lesbian culture form the year 2018)

Interviews (including the interviews where conversational analysis was done and those where it wasn’t)

Jodie Foster

Famous Jodie interviews

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mqxkA46eIOI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DiCwI4Xdvrk- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ct3UPiWPKS8

Jodie and gender

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X7p25iyvmsg&t=298s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTmjZf2NH3c

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ity8XVVSdI0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kQQrlGjeHIM

Jodie and sexuality

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-NqLsPfEras

https://youtu.be/243NYLOn6WE?t=122

Kristen Stewart

Heterosexual Interactions and “Chemistry”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sE0fPDIKGD8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NhlS_TikKXE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fREjpeShur0

On Sexuality

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GUMHSDzLBy4

Discussing Engagement

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ItTWGCJGTeA

Homosexual Indications

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZxvrV5UH2NE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nU6gCC3DTCc

Amanda Seyfried

About her boyfriend

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-GSou1Dk0hc

On her Marriage and Homelife

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TbRtVJYUADs

Brooke Shields

On matters of sex and sexuality

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J31pcI3ZgN4&ab_channel=MervGriffinShow

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6ge0xcs_jc&ab_channel=CristinaP

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTSSBJ6xyi4&ab_channel=TheDianeRehmShow

Romance

https://youtu.be/IjrVzyJEq3Y?t=659

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3QWQ4gN3j4E&ab_channel=WatchWhatHappensLivewithAndyCohen

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=htnMcHxr-Dw&ab_channel=MichaelMYoung

On Motherhood

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A9j2ZPcSCR4&ab_channel=BobbleheadConan

References

Clayman, Steven and Virginia Gill (2012). “Conversation Analysis.” In James P. Gee and Michael Handford, (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis. London, Routledge: 120-134.

jackson, april. (1994). Semantic Space: Bringing Lesbian Language Out of the Closet. Off Our Backs, 24(10), 13–13.

Jacobs, G. (1996). Lesbian and Gay Male Language Use: A Critical Review of the Literature. American Speech, 71(1), 49. doi:10.2307/455469

Jones, L. (2018). ‘I’m not proud, I’m just gay’: Lesbian and gay youths’ discursive negotiation of otherness. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 22(1), 55-76. doi:10.1111/josl.12271

Kachel, S., Simpson, A. P., & Steffens, M. C. (2017). Acoustic correlates of sexual orientation and gender-role self-concept in women’s speech. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 141(6), 4793-4809. doi:10.1121/1.4988684

Kulick, D. (2000). Gay and Lesbian Language. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29(1), 243-285. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.243

Lakoff, R. (1973). Language and women’s place.Language in Society, 2, 45–80.

Shrikant, N. (2014). “It’s like, ‘I’ve never met a lesbian before!’”. Pragmatics. Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association (IPrA) Pragmatics / Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association (IPrA) Pragmatics, 24(4), 799-818. doi:10.1075/prag.24.4.06shr

Sidnell, Jack (2013). “Basic Conversation Analytic Methods.” In Sidnell and Stivers, Handbook of Conversation Analysis, pp. 77-99.

Tannen, D. (Ed.). (1993). Gender and conversational interaction. Oxford University Press.