Catherine Guzman, Joan Kim, Kiara Mares, Yadira Marquez, Flor Ramirez

College enrollment and graduation rate from Latinos has increased during the last decade. Latinas[1] went from being 17% of graduates in 2000 to 30% in 2017. Latina mothers have played an important role in the success of Latinas by either providing motivation or pressuring them. Latina daughters may also face more pressure to understand the role that family dynamics and cultural roles play in their education and professional life, and it is our goal to show what factors influence the expectations of immigrant Latina mothers as well as how they communicate this to their children. We analyze word choice such as pauses and filler words, positive and negative word connotation, achievement remarks and associations, and levels of details to understand what factors influence what is expected of Latina daughters. Through the analysis of interviews of two Latina mothers with their older and younger daughters, we expect to find a positive correlation between the different levels of educational expectations based on birth order and expect the older daughter to have more responsibility and expectations of success.

[1] Latina: a woman or girl of Latin American origin or descent

In its everyday use, language is constantly changing. It adapts to best fit the current needs of a society and reflect what is culturally relevant. When analyzed correctly, language is a record of a culture – relating norms, cultural roles, dynamics, etc.

Take a look at the following quote:

“The father, what he wanted was that his daughter leave the house dressed in white and that was his goal” (Perez, excerpt 8).

Without further context, this excerpt allows for some insight as to what gender roles and familial expectations characterized this speaker’s community. Here, there is an emphasis on community and culture, because the speaker’s expectations have been determined by the interactions within their own community, which in turn, is reflected in their use of language.

This is not a new take on language and can be tied back to symbolic interactionism. This theory posits that meaning is constructed through everyday interactions and conversations (“Symbolic Interactionism Theory”, 2014). In other words, much of what we come to value, identify with, expect, draw meaning from, etc., was learned through our interactions with others within our community.

This is the framework that formed the basis of the present study. With a focus on word choice, our interest was with Latina immigrant mothers, women who grew up within Latin American norms and expectations, then found themselves having to immerse themselves into a new culture and unfamiliar social contexts (often resulting in conflicting interactions).

According to prior research, Latina immigrant mothers’ perceptions of education are impacted by interactions in both American and Latin America social contexts. To illustrate, in Mexican culture, women are often expected to prioritize familial obligations over their education (Perez, 2009). In addition, women in Mexico are expected to be most involved in their children’s lives, while in the U.S., it is common for both mother and father to work (resulting in comparatively less involvement) (Perez, 2009). Overall, prior findings support the assertion that immigrant women often form judgements from experiences and meaning created during early-life interactions (Perez, 2009).

With the intention of seeing how these findings manifested within an immigrant mother’s direct interactions with their children, we were looking to explore the following: What factors influence the expectations of immigrant Latina mothers? How do they communicate this to their children?

The study’s analysis was collected via informal interviews with two Latina immigrant mothers. Mother 1 is from Jalisco, Mexico. She immigrated to the U.S. 41 years ago, at age 8. Her two daughters are 19 and 16 years old. Mother 2 is from Oaxaca, Mexico. She immigrated to the U.S. 30 years ago, at age 16. She has two daughters, ages 19 and 23.

We hypothesized that Latina immigrant mothers have higher expectations for their older daughters. These expectations take the form of expecting the daughters to attain a higher education. We further hypothesized that Latina immigrant mothers would demonstrate these ideals through word choice, specifically, through the use of more positively correlated words and less fillers when being interviewed about their daughters’ educational goals.

In order to investigate our hypothesis, we had each daughter interview their respective mothers- mother 1 was interviewed by her oldest and youngest daughter and mother 2 was interviewed by her oldest and youngest daughter. The younger and older daughters each asked their mother the same series of ten questions (see the list of questions below), but they interviewed their mothers on different days and asked the questions in different orders. Each of the younger daughters asked the interview questions on the first day, and, then, a few days later the older daughters interviewed their mothers.

We recorded these interviews in order to be able to transcribe them so that we could make note of the following nuances in the mothers’ speech patterns: pauses, filler words, connotative word choice, levels of detail and any phrases that may allude back to gendered expectations. For the purpose of our research, we took pauses longer than two seconds into consideration; we did not analyze one second or less than one second pauses because we interpreted them as the mothers taking a moment to formulate their thoughts. We analyzed pauses longer than two seconds as an indicator of hesitancy on the mothers’ behalf about how they should respond to the question that was posed to them. We counted all the instances of filler words such as “Ah,” “Ahm,” “Uh,” “Uhm,” “Eh,” “Ehm,” and “Mmm ”as markers of hesitancy when preceded or followed by a pause as well.

We also used the context of the mothers speech to determine what pauses or fillers the mothers used to give themselves time to think and what pauses or fillers the mothers used when hesitant about how to deliver their responses. In addition to that, we also focused on words such as “orgullosa,” meaning proud,” or “gusta,” meaning “like,” as samples of connotative word choice in order to quantify how approving or disapproving the mother was in her response. We noted the amount of detail mothers went into in their responses for each question from the interview with their youngest daughter and cross referenced it with the length of their response from the interview with their oldest daughter. We made note of this, in order to determine if going into more or less detail with one daughter or the other had any implications in regards to their expectations for each daughter. While doing all of that, we also analyzed the data for any instances of references to gendered expectations the mothers brought up to draw conclusions about how well the educational expectations the mothers held for their daughters aligned with gendered expectations that are typical of Latinx culture.

Before we discuss our results, click this link: Latina Mothers in order to hear the audio.

The word choices in the recorded interactions were meant to indicate hesitancy or show intention in the responses, with a special focus on the answers from the mother. Filler words and phrases were tallied specifically with consideration that it might mean there was more difficulty finding a word, alluding that mothers felt the need to be more intentional with their responses. While there was a very large contrast between the amount of them the mothers used, the results indicated that amongst them both, they used more filler words with their older daughters. Specifically Mother 2 used 17 filler words with her youngest daughter and 23 with her oldest daughter. Similarly, Mother 1 used 2 filler words with her youngest daughter and 4 with her older daughter. This observation was especially interesting, given that in both cases the older daughters interviewed their mothers after the younger ones had so despite having already been primed 2 days prior, there was still more use of filler words with older daughters.

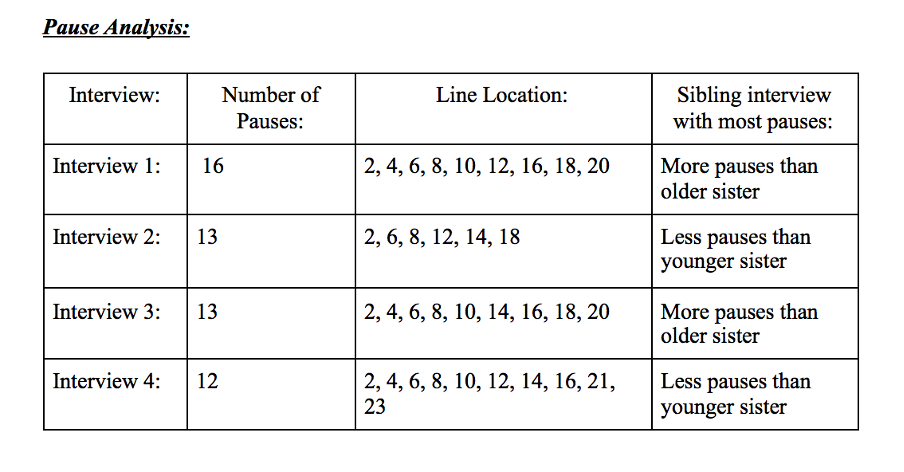

Pauses had the opposite results. When tallying we counted pauses above two seconds, and found that both mothers used more pauses when communicating with their younger daughters. In this case the mothers used a similar amount of pauses despite the location varying. Mother 2 used 16 pauses with the younger daughter, compared to just 13 pauses with the older one. Mother 1 used 13 pauses with the younger daughter and 12 pauses with the older daughter. Analyzing pauses was done with the intention of considering their hesitation when answering questions in a certain way. Overall this analysis indicated that when speaking with their younger daughters, the mothers used more pauses for their younger daughters. This could signify that the word choice required more thought and was more selective. However, it is also important to recognize that this length in pauses could be attributed to the younger daughters interviewing their mother first.

The next part of the analysis consisted of finding words that held strong positive or negative connotations. We immediately noticed that there were not any explicit words that had negative meaning or were used to allude to something in a negative light. On the other hand, we were pleasantly surprised with the amount of words with positive meaning. Although they were used in varying contexts, both mothers expressed about the same amount of positive words. Most of these words overlapped in all conversations, with some of the most recurrent being “orgullosa” meaning ‘proud’, “exitosa” meaning ‘successful’, and “gusta” meaning ‘liking/liked’. Each word was interpreted as approval of their accomplishments or what they’re doing academically. These positive words were evenly spread among all interviews and didn’t indicate any biases for stricter expectations with one or the other daughters. One interaction that exemplified the role of maternal figures in setting expectations, was Mother 1’s response to the question “What do you think about my goals compared to the cultural expectations you grew up with?”. She responded with, “Esta buena pregunta para tus abuelas”, ‘this is a good question for your grandmothers’ possibly implying that expectations for women are set by the women that raised them.

Finally, our study analyzed the level of detail provided in the responses. The purpose of taking detail into consideration was to see if the mother was involved more with one daughter than the other or if the mother felt the need to explain her responses because of a more demanding expectation to either of her daughters. While the answers varied in length, there was an increased length in the responses for the older daughters from both mothers. This again could indicate that mothers feel the need to reinforce specific goals and expectations more thoroughly to their older daughters.

However, in studying this we observed other responses that supported our hypothesis that Latina immigrant mothers held higher expectations for their elder daughters in comparison to their younger daughters. The first question being “How do you feel about my career choices?” where Mother 1 explains to both daughters that she is content in their choices. However, she then goes on to note that her older daughter’s aspirations are rather competitive and she wants to see them all the way through. This was in contrast with her response to her younger daughter where she suggested a career in Broadway, which is much more difficult to land a secure spot in. This response perhaps shows that the mother wants her older daughter to be more secure in her career choice, followed by the expectations of being in a stable job — expectations not found in the interview with her younger daughter.

In summary, our study found that with the cases given, we were able to find some indications of older daughters being held to a higher career standard. Such instances were found in word choices analyses regarding careers and education. Specifically, we were able to find patterns of correlating pauses and filler words, and were even able to find patterns of expressing more detailed answers to older daughters. However, due to certain limitations (to be specified in subsequent paragraphs), it is clear that these findings are not substantial enough for a definitive conclusion.

Our research would benefit from further research to argue for a more solid conclusion. Additional exploration and analysis on our test subjects and methods could provide more substantial evidence for whether or not Latina immigrant mothers have higher expectations for their first eldest daughters compared to the youngest.

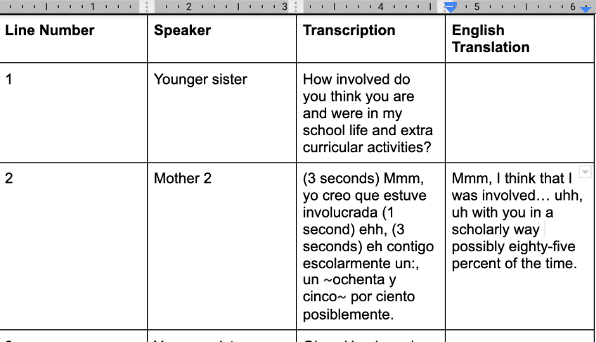

Our research limitations consisted of a few things. First, out of the interest of time, our interviewees were only allowed ten questions to ask their mothers. These questions did not include follow up questions, which would have greatly expanded on certain ideas. For example, one instance that could have benefitted from more explanations from both responses is to the question “How involved do you think you were and are in my school life and extra curricular activities?”.

To expand, one mother replied with “..un ~ochenta y cinco~ por ciento posiblemente” ‘possibly 85 percent’ for both daughters. This mother only expands briefly when talking to her older daughter, ranging her involvement between elementary school and high school. However, one way to have gained more qualitative data would have been to ask specifically in what ways this mother came to the conclusion of 80 percent.

The other mother responded with “I am very involved in the activities and studies of my daughters” for the younger daughter and “Very, very much in school” for the older daughter. Similar to the previous mother, a follow up question of asking “How so?” or “In what ways?” could have provided more data to compare to with the first mother, in regards to what these two mothers did to stay involved.

Moreover, our study only used two mothers, therefore, our work should be considered as a case study rather than extensive research. It is only a small representation of the Latina motherhood community. On a similar note, with only two mothers, it was difficult to compare and draw conclusive statements. However, if there were more resources, subjects, and time allowed, these limitations could be reduced.

These findings may contribute to a larger phenomenon on who maintains such expectations in a Latina community, as well as connecting to as far as how this affects a woman’s social identity in her aspirations.

References

Aviles, G. (2019, November 20). More Latinas have college degrees, but they’re still making less than white males. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/more-latinas-have-college-degrees-they-re-still-making-three-n1087101

Clark, H. H., & Fox Tree, J. E. (2002, February 27). Using uh and um in spontaneous speaking. Retrieved from http://www.columbia.edu/~rmk7/HC/HC_Readings/Clark_Fox.pdf

Crosnoe, R., Ansari, A., Purtell, K. M., & Wu, N. (2016). Latin American Immigration, Maternal Education, and Approaches to Managing Children’s Schooling in the United States. Journal of marriage and the family, 78(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12250

Field research. (n.d.). Retrieved May 11, 2021, from https://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/datamethods/fieldresearch.jsp

Mendoza-Denton, N. (2008) “THAT’S THE WHOLE THING [tɪŋ]!”: DISCOURSE MARKERS AND TEENAGE SPEECH. In J. McIntosh (Ed.), Homegirls (pp. 265-291). Wiley.

Perez, A. (2009). Understanding Attitudes about Education within two Cultural Contexts: Comparing the Perceptions and Expectations of Mexican Mothers in the Greater Los Angeles Area to their Cohort in Mexico. Graduate Studies At California Lutheran University.

Symbolic Interactionism Theory. Communication Theory. (2014). Retrieved May 2021, from https://www.communicationtheory.org/symbolic-interactionism-theory/.