Hyung Joon (Joe) Kim, Jenny Elliott, Madeleine Song, Sophia King, Alison Tcheguini

With the rise of social media influencers, online public figures have become more attentive to how they communicate with their followers. In our research study, we assess the features of online gendered communication in comparison to the in-person gendered communication theories.

To do this, we chose YouTube fitness influencers as our main scope of study because “fitness” is a relatively gender-neutral category. By analyzing the influencers’ online comments, we discovered notable differences between male and female influencers’ responses to their fans. We found that women use certain linguistic features more frequently and that they used them in greater varieties. We believed this to be an indication of an emotional and expressive way of communicating. On the other hand, men generally used these linguistic tools less frequently and in less variety.

Overall, both males and females used supportive and rapport language. This is indicative of the fact that both seek to establish solidarity with their respective fan base. However, we found that men and women use these linguistic features to different extents, and differing the types of linguistic tools they use. In this regard, we observed a dichotomy of “calm vs emotional” which is a modern adaptation of the well-established “report vs rapport” model.

Introduction

Regardless of their content, social media influencers aim to grow and maintain an audience to ensure their platforms are marketable and profitable. We found there are several linguistic techniques these influencers adopt to build connections with their fans. In particular, they replied to their followers’ comments under their videos to facilitate connection with their audience, and, when doing so, utilized rapport-building linguistic features.

In general, men and women have been understood to communicate differently in the process of forming connections. We wanted to further investigate differences across genders in connection-building communication in the context of online social platforms.

These concepts guided our research, as we examine the linguistic differences of male and female influencers in their written responses to followers’ comments online.

Background

Due to our scope of interest in influencers’ platform maintenance, we examined existing literature on gendered and computer-mediated communication.

The dominance model suggests that female language use reflects male dominance in society (Lakoff, 1975), whereas the difference model proposes that differences in language between men and women reflect different cultures of conversation (Tannen, 1990). Despite both styles serving the same communicative function, women use rapport-oriented conversation, which is more emotional, while men use report-talk, reporting fact-based information and competing for hierarchy in conversation (Tannen, 1990). Further work has been done on gendered communication differences to see what linguistic features can be attributed to men: in homosocial contexts, men use expressions like “dude” or “bro,” as their way of performing male expectations, indexing their heterosexuality to promote heterosexuality as their preferred orientation. (Van Herk, 2018, p.109).

Since we are looking at social media influencers, we also looked at computer-mediated communication (CMC) studies to see how these patterns reflect in a modern online context. The content of CMC messages by females is more expressive than males, reflecting a female’s social role of being emotionally expressive and collaborative, as mentioned in the Tannen’s model (Fox et. al., 2007, p. 395). Regarding CMC-specific linguistic features like emoticons, studies suggest that females use emoticons as a means of expressing solidarity, support, positive feelings, and gratitude––reinforcing the existing stereotype that females are more emotional than males (Wolf, 200, p. 827). Literature on text-based punctuation in online messages suggests that digital cues, such as excessive punctuation and capitalization, increased the bonding of female friendships (Sherman et. al., 2013). These cues were made frequently by young women to convey emotion in their text-based conversations.

Our main research question is the following: “To what extent does the gender identity of YouTube fitness influencers affect the digital linguistic expressions they use to establish solidarity with their followers?”

In our research, we observed that females used more frequent expressions than males across four different features we examined; however, by narrowing down on more specific sub-categories under the features, we found that even though males and females used different linguistic expressions, both male and female fitness influencers were using different tools to pursue the same purpose of establishing solidarity with their fans.

Methods

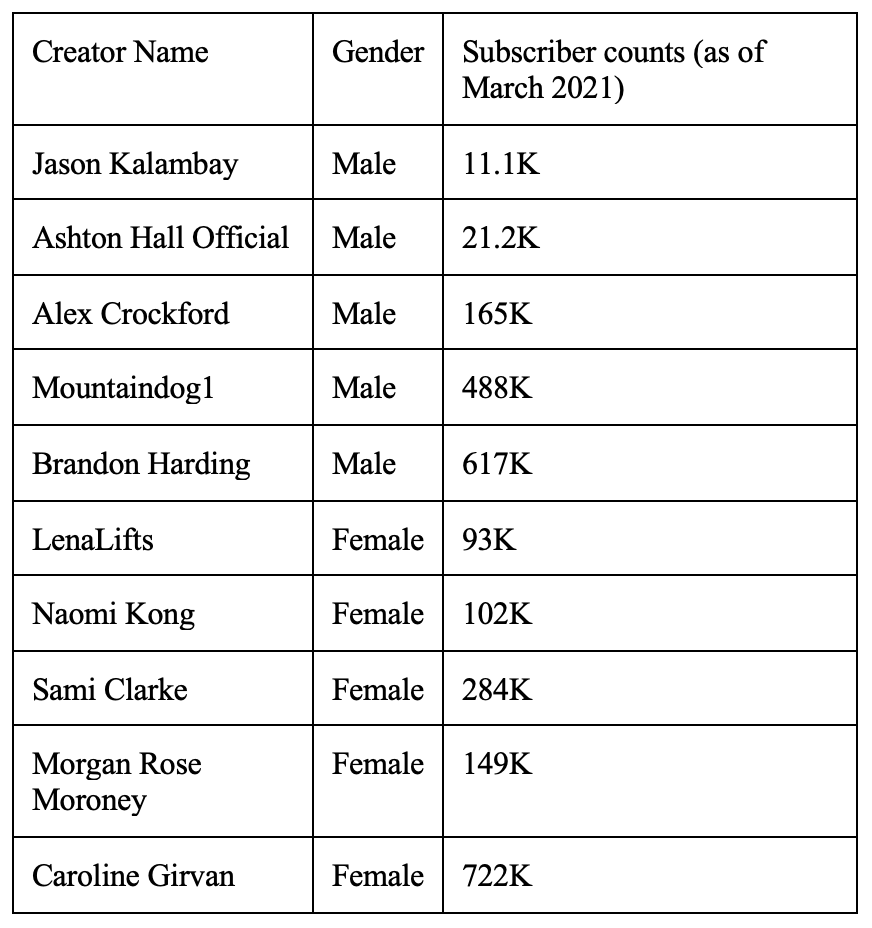

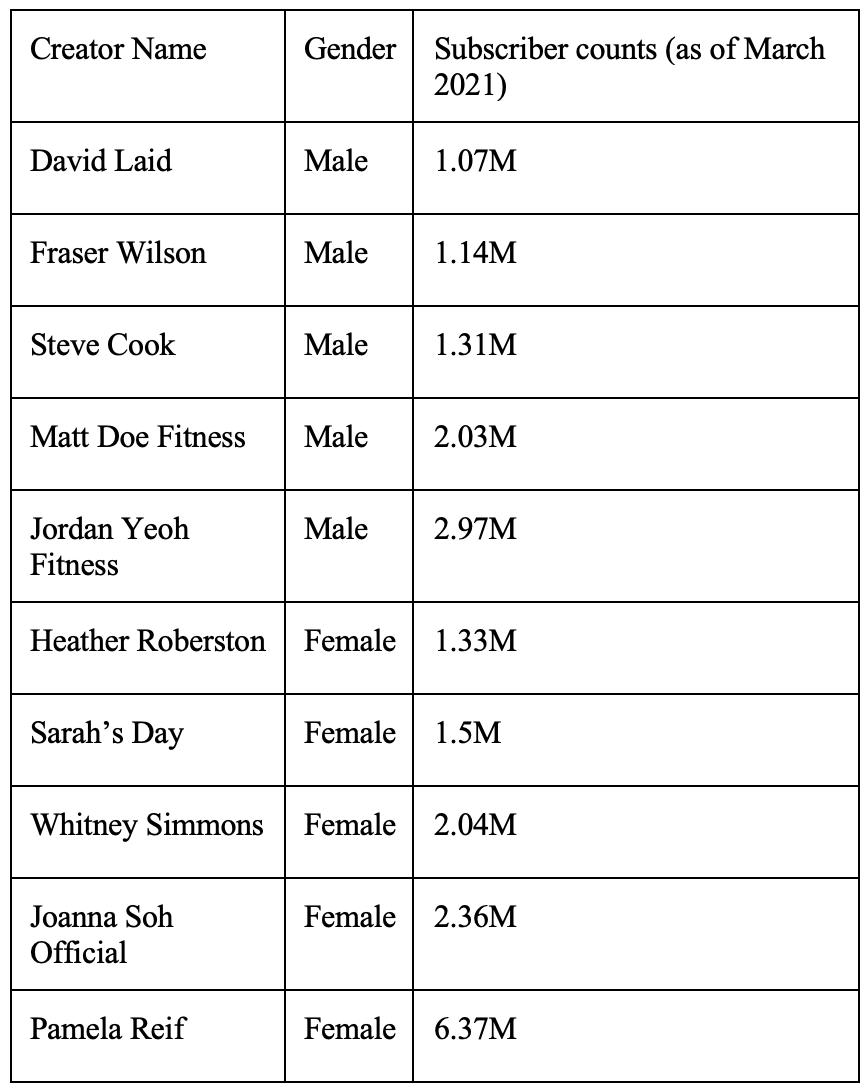

We conducted our study by analyzing the computer-mediated communication used by ten female and ten male YouTubers. We narrowed our sample choice by selecting YouTubers who belong to the fitness industry, create fitness content for YouTube, and speak English. Our sample was categorized into two sections: influencers with less than one million subscribers (Table 1) and influencers with over one million subscribers (Table 2). To avoid bias, data were collected from each influencer by randomly selecting ten interaction-based comments from two randomly selected workout videos.

We categorized our data into four linguistic features based on the most salient differences we observed among the comments of male and female fitness influencers. Our data was analyzed based on the frequency of emojis, exclamation points, capitalization, and pet names. In terms of emojis, we looked at the types of emojis that were being used differently by males and females. The specific emojis were grouped into three distinct categories: facial expressions, gestures, and non-human symbols (fire, stars, sweat, etc).

Results and Analysis

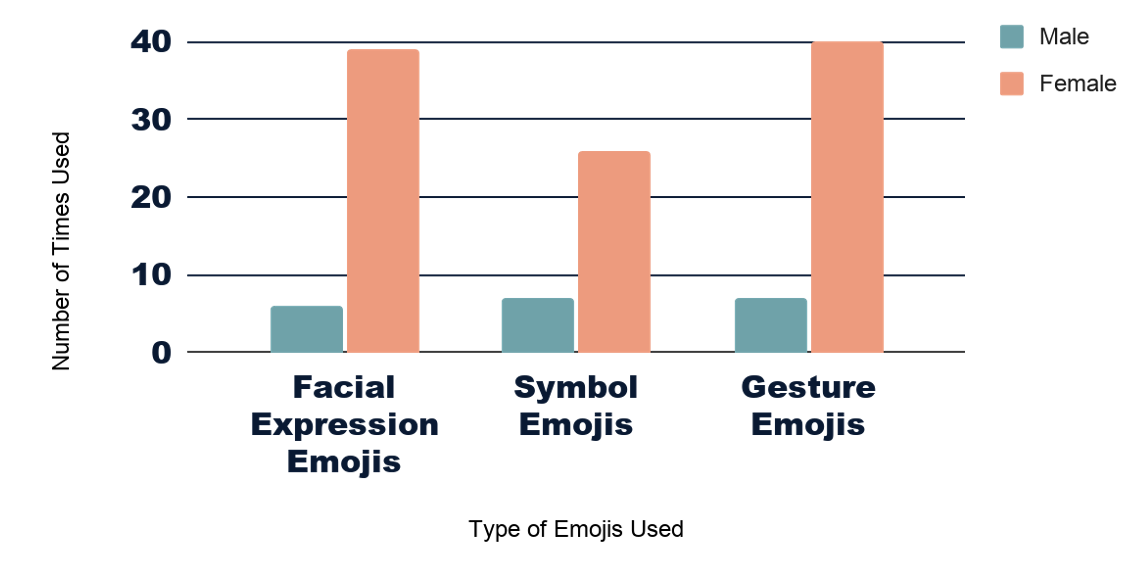

First, we looked at the use of emojis in YouTube comments from female and male influencers. Symbol and facial expression emojis were popular for women, using a variety of faces such as 🤪 and hearts 💖.

Men also used emojis frequently but the specific emojis they used differed from what females used––males instead opted for symbols like 🔥 or 💦.

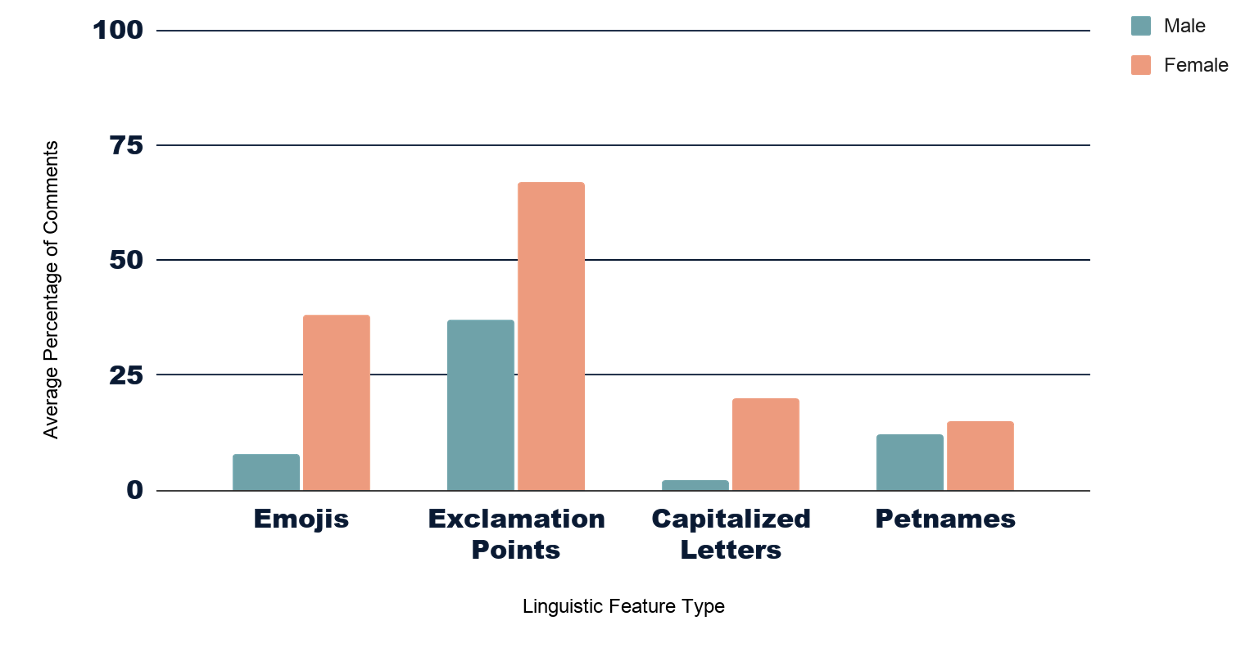

Overall, women used more expressive facial emojis along with many gesture emojis (Figure 1). In general, women used facial expression, symbol and gesture emojis more frequently than men.

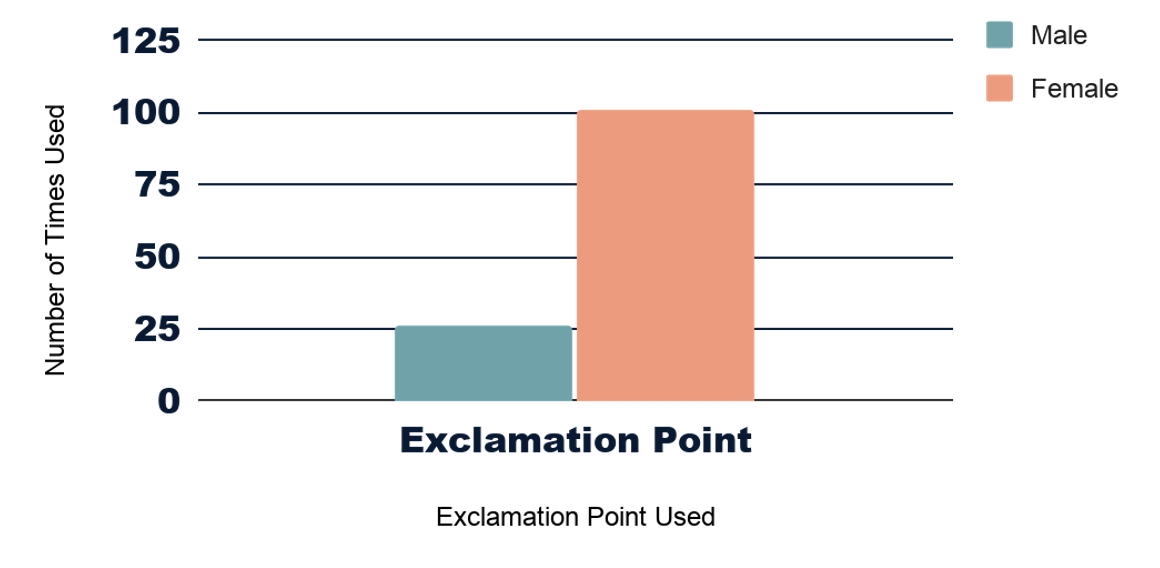

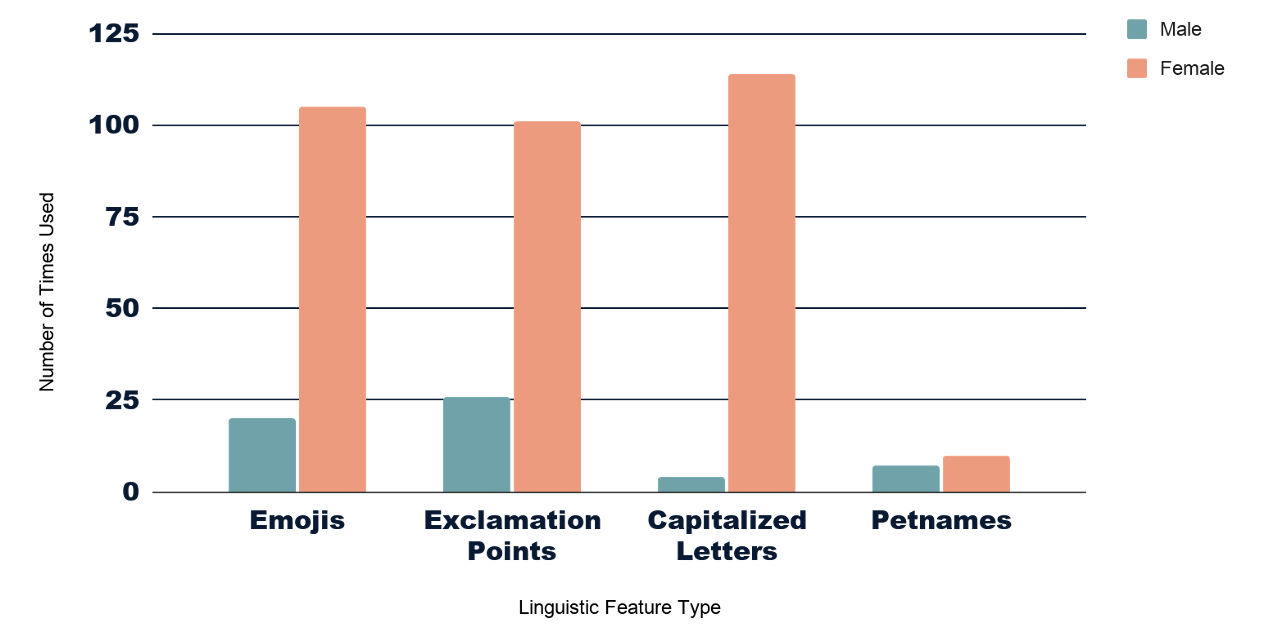

Second, we analyzed punctuation by examining the use of exclamation points in influencers’ responses to comments. Women tended to use exclamation points in most of their replies, often using several exclamation points in a row. In contrast, males did not use exclamation points as frequently, and when they did, they only used 1-2 per comment.

While men did use exclamation points, they did not use them to the same extent as women. Women used exclamation points more frequently, totaling over 100 times throughout comments compared to just over 25 by men (Figure 2). The number of comments in which these features appeared was identical for male and female. Females typically used digital cues including excessive punctuation to better convey emotion online.

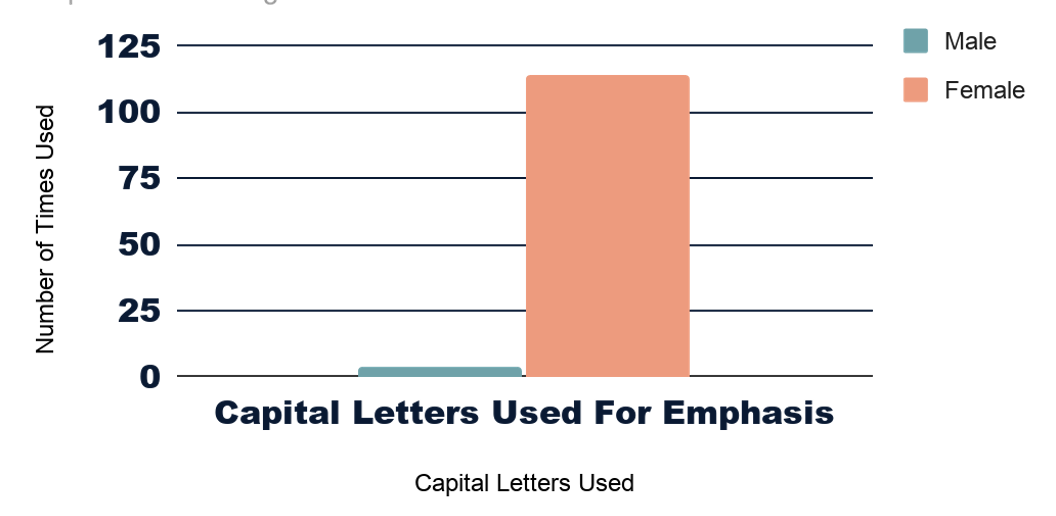

Next, we considered influencers’ usage of capitalized words within sentences. We found that female influencers were more inclined to capitalize individual words or phrases when replying to comments. Women often capitalized words of encouragement like “good job” yay” or “yesss”. Conversely, men rarely utilized the capitalization of words.

The capitalization of words (particularly for emphasis) was used by females at a higher rate than their male counterparts. Whereas women did this over 100 times throughout our data, men did not even reach a count of 5 (Figure 3).

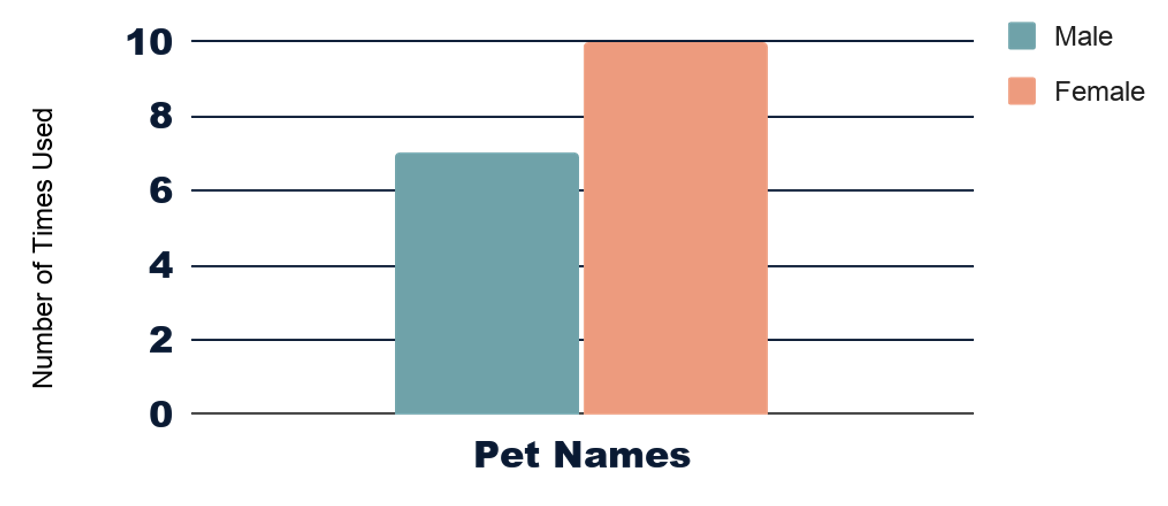

Finally, we looked at the pet names influencers used when responding to comments. Female fitness influencers often used words such as “girl,” “queen,” and “babe” to address their followers, whereas males used terms like “man,” “buddy,” and “mate” to address their followers in a similar supportive fashion. Figures 5 and 6 display the overall comparisons of the four linguistic features’ rate of appearance in 10 comments written by the male and female social influencers.

We observed that females used pet names more frequently than males, but the difference was not as large (Figure 7).

Discussion and Conclusions

There are four key insights that summarize our research results.

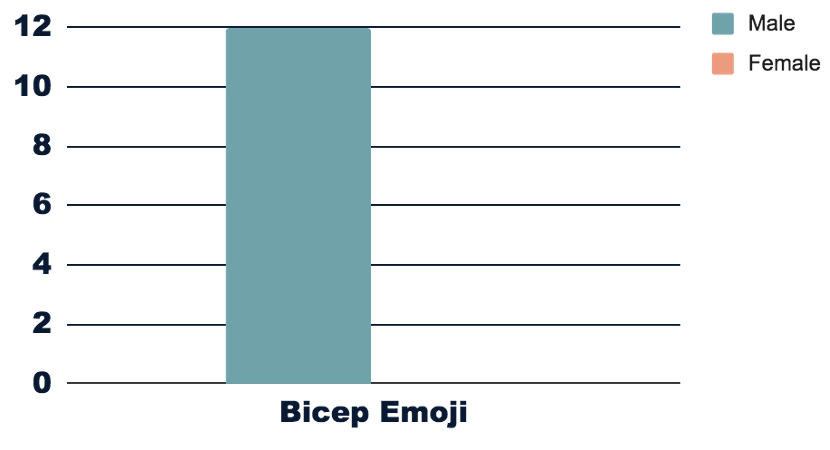

First, by taking a closer observation at the types of emojis male influencers used, we found that males usually used bicep emojis whereas females did not use them at all. Females generally used more emojis across all emoji categories. However, by narrowing down to a more specific sub-parameter within symbolic emojis, we observed that males were in fact using a different tool to strengthen their relationship with their predominantly male fans.

First, by taking a closer observation at the types of emojis male influencers used, we found that males usually used bicep emojis whereas females did not use them at all. Females generally used more emojis across all emoji categories. However, by narrowing down to a more specific sub-parameter within symbolic emojis, we observed that males were in fact using a different tool to strengthen their relationship with their predominantly male fans.

This insight suggests that in CMC, both males and females likely strive to establish solidarity with their fans but through different linguistic tools. On social media platforms, influencers of all genders are driven by financial motivations to attract viewers by crafting themselves as more responsive and supportive than their competitors.

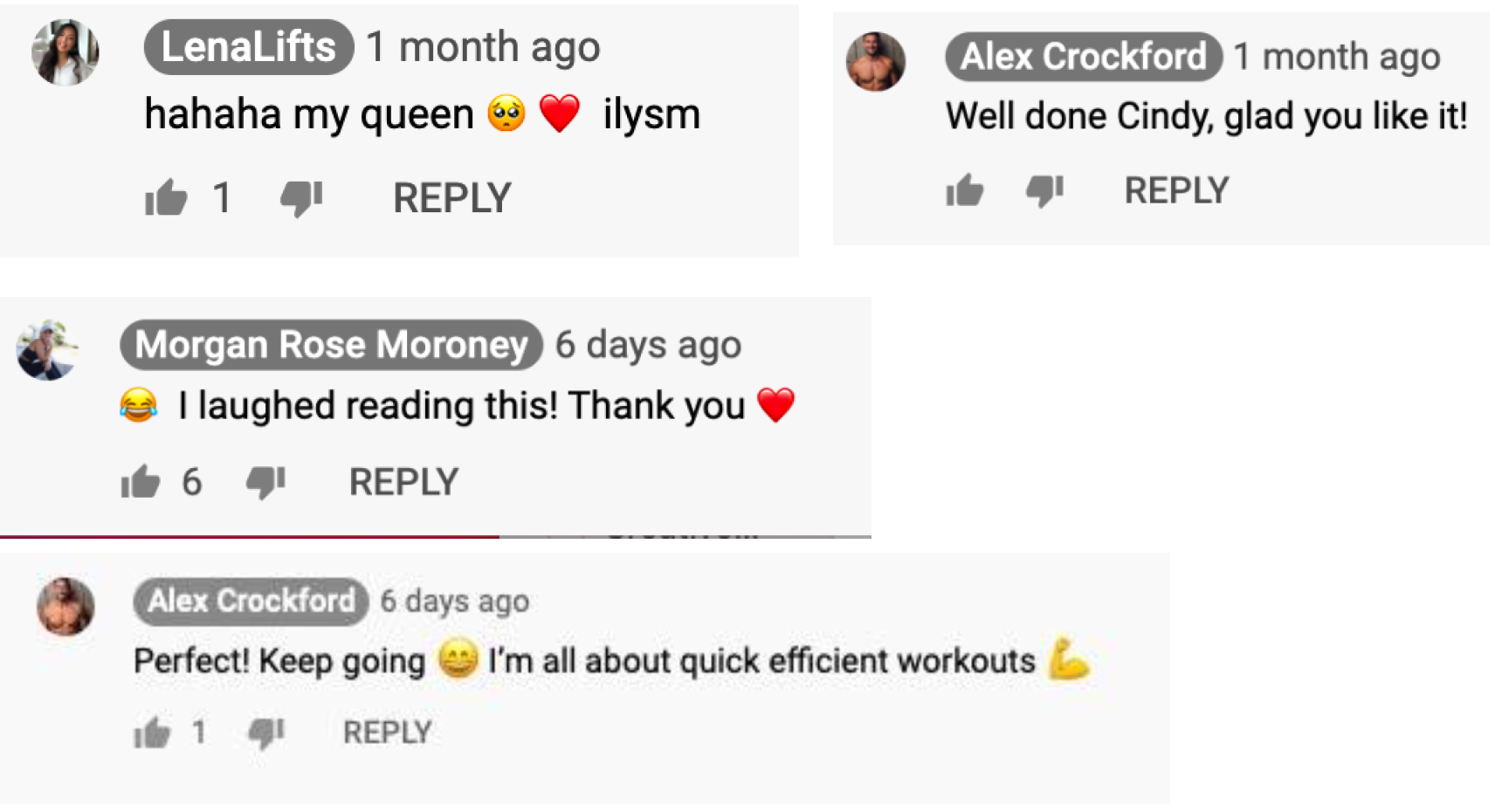

Second, the nature of the male influencers’ comments was more action-oriented than that of female influencers’ comments. For example, males often posted comments such as “Keep going” and “Well done!”, whereas females often posted gratitude-expressing, emotional comments such as, “Thank you!!!” and “ILY MY QUEEEEN”.

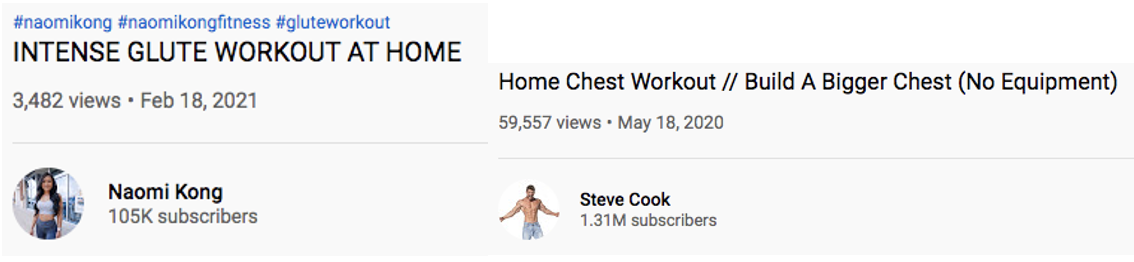

This second point illuminates that most of these interactions took place between same-sex followers and influencers. This phenomenon could be attributed to the fact that the fitness objectives of the videos were inherently geared to target the followers of the same sex as the influencers. For example, we noticed that the majority of the videos created by female fitness stars tend to have titles such as, “Intense Glute Workout”, but males posted videos with titles like “Build a Bigger Chest”. These fitness videos align the body areas that respective genders tend to visually prioritize when developing their body muscles. In general, females are more self-conscious of their leg and glute areas whereas males typically focus on building the size of their upper body.

Third, we observed a dichotomy of ‘emotional vs calm’ which is a digital adaptation of the ‘report vs rapport” model. In particular, male influencers’ average length of comments is significantly less than female influencers’ average length of comments. The male influencers’ responses were calmer than those female influencers. We think this ‘emotional vs calm’ dichotomy is a formal theorization of what computer-mediated gender communication can look like in the context of our digital influencer study. Our research also invites further studies by future socio-linguistic scholars interested in the intersection between gendered communication and online social media platforms.

Lastly, with male influencers specifically, we observed that those with a smaller following responded more frequently to comments than those with a larger following. Once reaching a certain level of popularity (over 1 million), males responded less frequently. We theorize this is because males use more feedback only before their platform grows to a certain level of popularity. Given that our study only examines 20 social influencers on YouTube, we’d like to invite future researchers to conduct more studies in these areas.

In short, our research study shows that females are predominantly more expressive than males across all 4 linguistic categories, but males have more frequently used bicep emojis in particular. In addition, even though females’ responses were visibly more expressive in terms of the frequency and variety of emoji usage, both males and females were pursuing the same purpose of establishing solidarity with their fans, by using different tools.

We argue that the Tannen model is being applied differently in the context of computer-mediated communication and the nature of social media, as social influencers, whether male or female – are in positions to appeal to their general audience. We also propose the “emotional vs calm” dichotomy observed from gendered communication in online platforms and invite further research to be done in this area.

Among several, one limitation of our research is that we did not incorporate the nature of the followers’ comments that the influencers responded to. In general, we observed that most viewers’ comments were positive, grateful, and supportive. This research invites future studies to undertake how the responses would look different towards comments that are hateful or negative. In addition, more studies on how non-famous males and females differ in their digital communication on social online platforms are needed.

References

Bamman, D., Eisenstein, J. and Schnoebelen, T. (2014), Gender identity and lexical variation in social media. J Sociolinguistics, 18: 135-160. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12080

Fox, A. B., Bukatko, D., Hallahan, M., & Crawford, M. (2007). The Medium Makes a Difference: Gender Similarities and Differences in Instant Messaging. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26(4), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X07306982

Herk, G. V. (2018). Gender. In What Is Sociolinguistics? (pp. 96-116). Wiley Blackwell.

Lakoff, Robin. 1975. Language and woman’s place. New York: Harper Colophon Books.

Sherman, L. E., Michikyan, M., & Greenfield, P. M. (2013). The effects of text, audio, video, and in-person communication on bonding between friends. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 7(2), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2013-2-3

Tannen, D. (1990). “Put Down That Paper and Talk to Me!”: Rapport-talk and Report-talk. In You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (pp. 74-95). HarperCollins.

Wolf, A. (2000). Emotional Expression Online: Gender Differences in Emoticon Use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3(5), 827–833. https://doi.org/10.1089/10949310050191809