Jaslin Mostadim, Briyana Bekhrad, Sofia Peykar, Talia Behjou, Ashley Javaherian

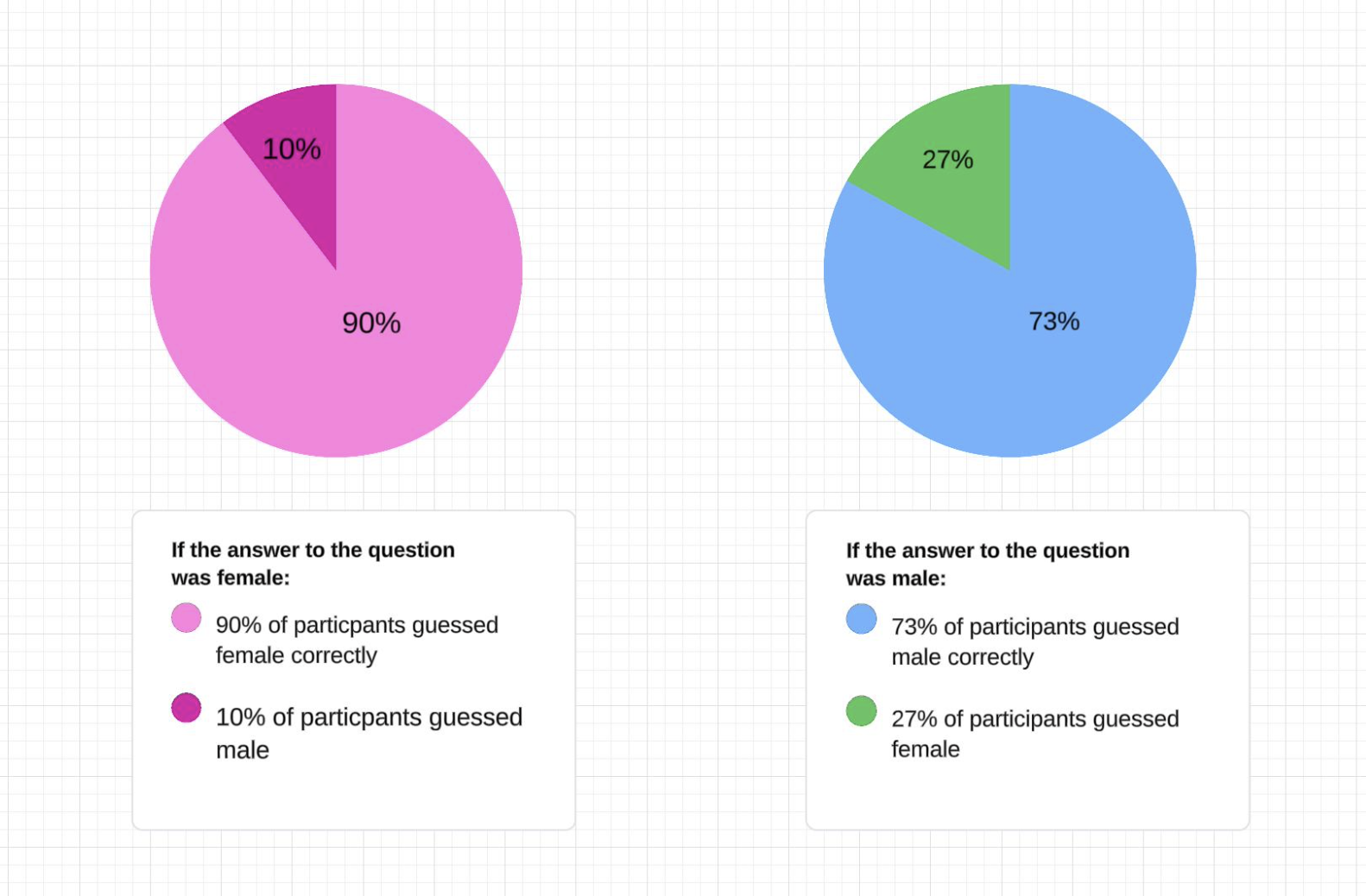

Imagine you just received this anonymous text, “Hiiii!!😊 ”, would you be able to guess the gender of this message? Well, what if we told you that although stereotypical, if you answered with “woman”, you would be correct. In a world that is majorly socially constructed, our research project attempts to examine the world of SMS communication and the gendered differences between males and females. To do so, our group conducted a two part survey consisting of 25 questions which enable us to decide whether or not communication via text message is gendered based on the following five factors: emoticon use, punctuation, abbreviations, tentativeness, and text length. Once data was collected, an analysis was performed which concluded that four of the five factors studied within our survey agreed with the societal expected norms for men and women when texting. The results indicate that women agreed with four of the five studied factors as they tend to use more emoticons, tentativeness, punctuation and longer texts when communicating in comparison to their male counterparts. As for the fifth factor, our study allows us to deduce that both men and women tend to use abbreviations in a similar fashion when texting. The conducted study found that 90%, were able to successfully answer females as the correct answer for the questions and 73% of participants were able to successfully answer males as the correct answer for some of the questions. This data supports that men and women have distinct communicative styles when texting as the majority of our participants were able to decide what gender that anonymous text was sent from. Our hypothesis was proven mostly correct in that socialized gender stereotypes affect the use of emoticons, punctuation, tentativeness and text lengths when texting.

Introduction and Background

There is no doubt that texting is one of the major means of communication, especially today. It allows us to communicate with who we please, when we please. But, our topic allows us to dive deep and determine whether there is a difference between male and female texting and if so, how the texting patterns differ. This was done through analyzing their uses of emoticons, punctuation, abbreviations, text length, and tentativeness. We already know that communication styles, more specifically while texting, can differ between other factors such as those in varying generations, but we are looking at exactly how these texting styles and mannerisms contrast between the female and male gender. We have identified a gap when it comes to understanding the miscommunication between males and females when texting, and have deduced that it is due to their opposing texting styles and strategies.

To mention, there are some pre-existing studies on some of our chosen texting patterns, such as Robin Lakoff’s Deficit Theory. Lakoff’s theory explores the idea that the use of tentativeness in communication is favored by women as they text with less certainty (Leaper et al, 2011). Similarly, another collective group of researchers have concluded that there are higher rates of tentative speech whilst texting in comparison to males (Ling et al, 2014). But, our research aims to conclude the genuine reasonings of these text choices and tactics between males and females through analyzing all five factors, and what it implies for the male and female gender categories. With our contribution, we will be able to find the source of this disconnect, understand the male and female texting patterns, and why such tactics exist. Our research is guided by the hypothesis that females and males text in accordance to gendered stereotypes with females using more emoticons, abbreviations, proper punctuation, longer texts, and more tentative messages than males.

Methods

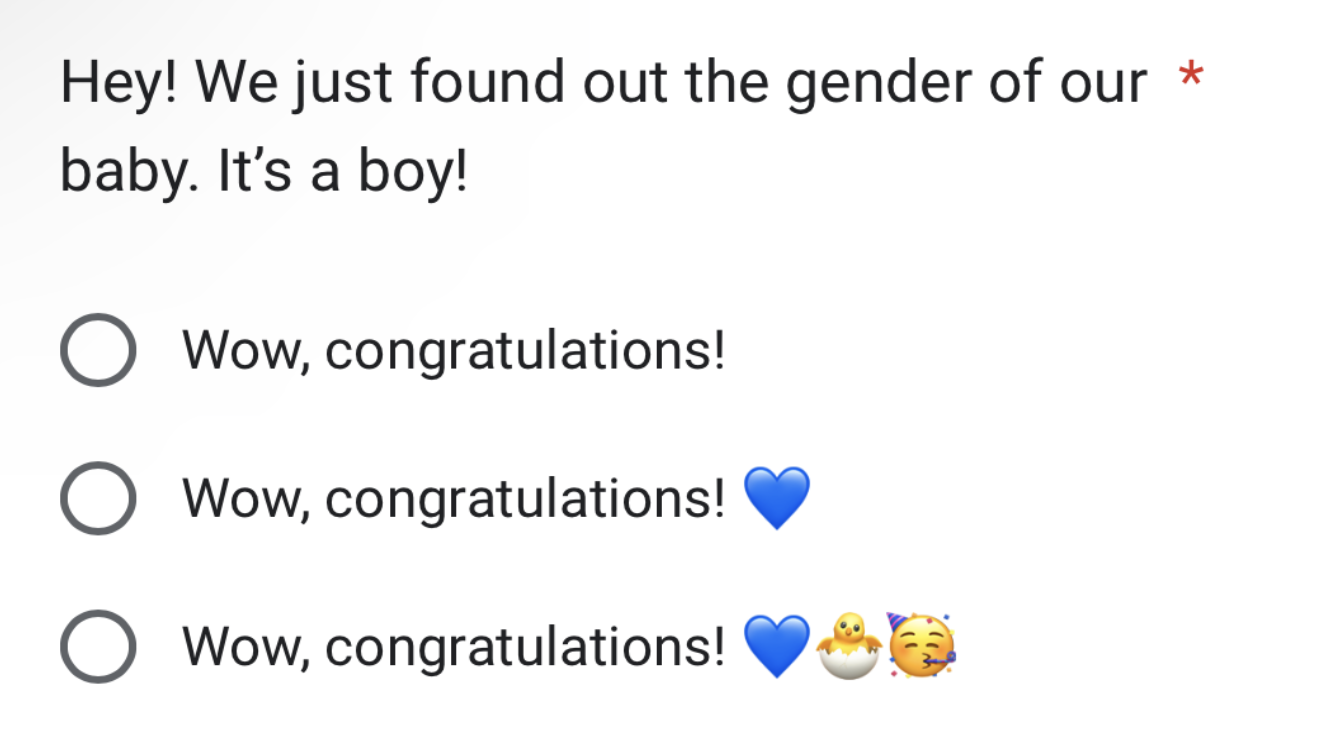

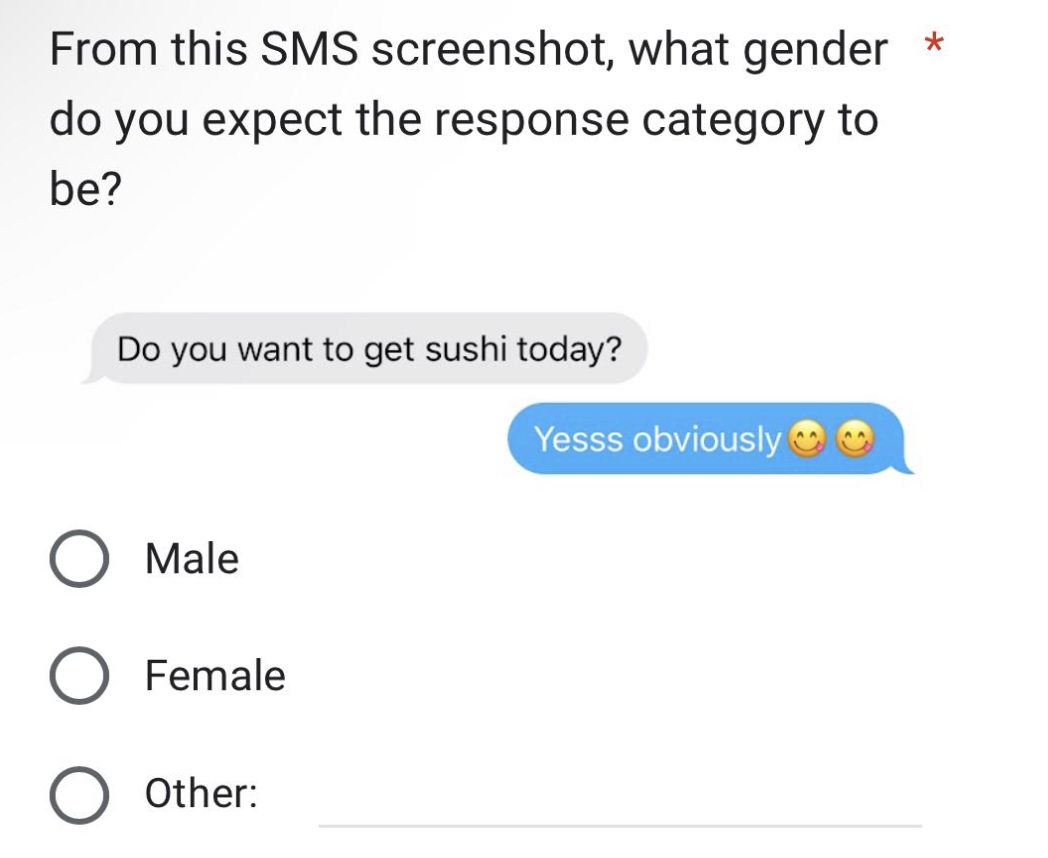

The target sample for our mixed methods approach includes 15 males and 15 females who are undergraduate students from UCLA, of ages 19-23, who regularly engage in text-based communication. The individuals partaking in the study are of homogeneous demographics and middle-class backgrounds. We will collect our data by administering a survey, which will contain two parts. The entirety of our survey will include 25 questions. The first part will include a message and three possible text replies with two questions regarding each of the five factors that we will study. When asked about the aspect we are observing, the response choices will range from least to most expressive. It is coded so that option 1 is hypothesized to be more popular with males while option 3 is coded to be more popular with females. An example of this can be seen in Figure 1. The second part of the survey displays a series of text message conversations that were sent in from our study pool and asks to identify if a male or female was responding. This approach will decipher whether and how SMS texting is gendered and its contributing patterns. This can be seen in Figure 2, which shows an example of a survey question.

Figure 1- An example question from the first part of the survey which is analyzing emoticon use by providing a test message and three response options.

Figure 2- An example question from the second part of the survey which asks whether they expect the response to be given by a male or female.

Results and Analysis

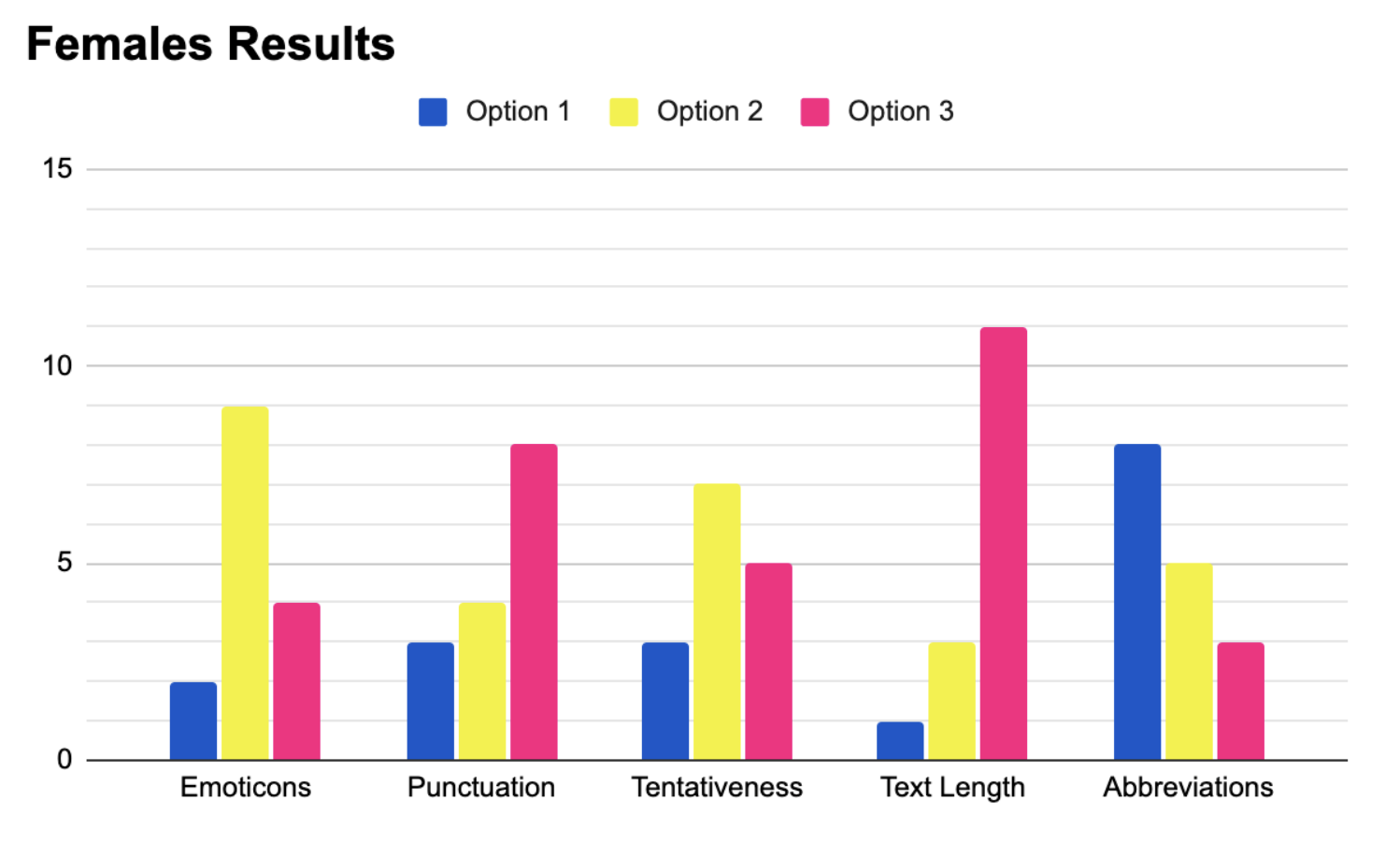

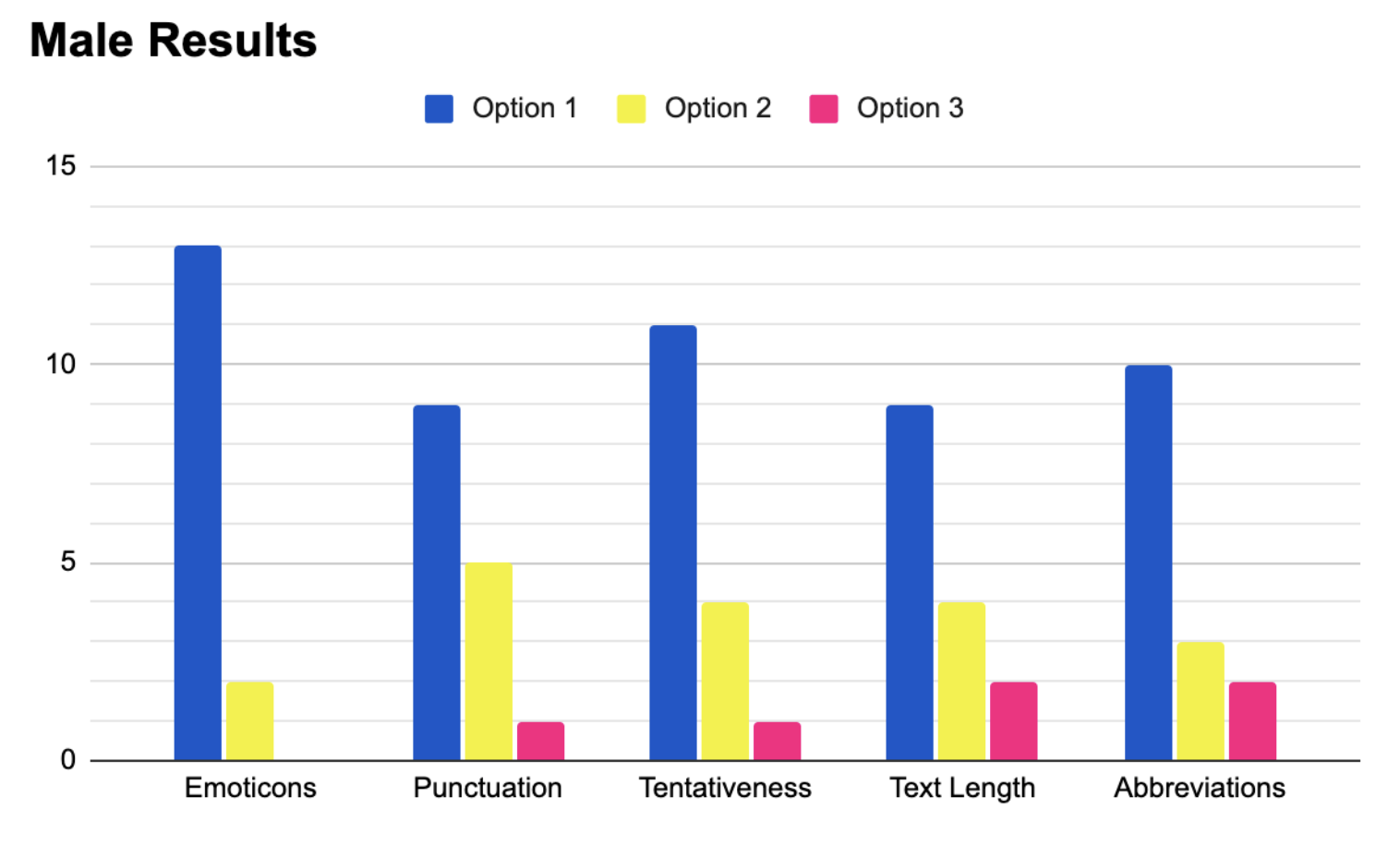

After analyzing our survey results, we found that our research supports the majority of our hypothesis of how texting communication patterns differ between men and females. By analyzing text messages and our conducted survey, it can be inferred that women tend to use more emoticons, punctuation, tentativeness, and longer text messages in comparison to their male counterparts. Although the other factors of our hypothesis were proven correct, we found that abbreviation usage is similar between males and females. These factors were not consistent with 100% of our respondents, but we were able to deduce that four out of the five analyzed factors agree with our hypothesis. As shown in Figure 3, 11/15 females chose option 3 for text length, while only 2/15 males chose option 3. Additionally, 60% of the males choose option 1, which proves our hypothesis in regards to text length. For punctuation, 8/15 females picked option 3, while just 1/15 males chose option 3. Instead the more popular option chosen by the males was option 1, which is shown in Figure 4. For all of the five factors, more than half of the males picked option 1 as their response to the survey questions, while the majority of females tended to pick either option 2 or 3. Also, our research proved that females were more likely to choose option 1 which was coded for males, in comparison to males choosing option 3 which was coded towards females.

Figure 3- Collected data from female participants from our survey regarding the five main factors studied. (First part of the survey)

Figure 4- Collected data from male participants from our survey regarding the five main factors studied. (First part of the survey).

The second part of our survey offered screenshots of text messages where the respondent decides whether they expect the text message to be sent from a female or male. Shown in Figure 5, our results gathered that 90%, or 27/30 participants, were able to successfully answer females as the correct answer for the questions, whereas 10% guessed incorrectly. We also gathered that 73%, 22/30 participants, were able to successfully answer males as the correct answer for some of the questions, whereas 27% guessed incorrectly. These results prove to us that males are less likely to text like females, because more participants were able to correctly answer the questions where the answer was “females.” This demonstrates the clear differences in texting styles between females and males, as most participants immediately identified the responses to some of these questions as female.

Figure 5- Results to the second part of our survey regarding the percentage of participants who answered the questions correctly relating to females or males. (Second part of survey).

A blog post that cross references with our research data discusses the “do’s” and “don’ts” of texting a female. The author of the blog starts out with, “Hello Gentlemen,…” aiming towards men only. Through our own research, we found that women text longer messages, whereas men are vague and text short messages. The author prompts; “If a guy texts me ‘Hey’ and nothing else, how am I to respond? With another “Hey”? or “Hey, How are you?” But then, the guy is making ME do all the heavy lifting of asking how he is doing when he wasn’t courteous enough to inquire how I was doing” (Elenamusic, 2013).” Our study as well as current research indicates that in one way men expect a more detailed response from women. This relates back to our hypothesis that women tend to use longer, more expressive and more tentative texting styles than men, and one reason is because society has socialized this gendered texting style. The author’s example shows the ambiguity in interpreting a short message like “Hey” from a male, focusing on tentativeness in communication, as the recipient is unsure how to respond. This text conversation implies that men’s short messages can put all the pressure on women to try to carry the conversation. This proves to our research how women usually text longer messages rather than men, texting short and vague messages.

Discussion and Conclusion

We analyzed the texting behaviors of male and female undergraduate students uncovering differences in their communication styles. Our findings provide evidence that females often use more emoticons, proper punctuation, tentativeness, longer messages. This is supported by previous literature that suggests that females favor displaying expression through emoticon use (Ceccucci et al, 2013). Additionally, women were found to use more expressive punctuations, following the theme of expressive messages (Waseleski, 2017).

Aligning with previous studies, our results demonstrate that females consistently use more emoticons and longer texts while males use few to none emoticons and fewer words. Emoticons and text length serve as emotional cues, allowing females to emanate their emotions via text-communication. Females were also found to use proper punctuation and abbreviations in their messages to enhance clarity and efficiency in their messages. Lastly, females compose more tentative messages, characterized by the use of hedge words such as “maybe.” Hedge words and tentativeness display uncertainty which aligns with traditional gender norms of masculinity and femininity. Furthermore, females and males tend to display similar patterns when it comes to the use of abbreviations. Keong’s study agrees with our findings as it explains that males and females use abbreviations at similar rates (Keong et al, 2012).

Our study highlights the importance of understanding gendered differences in texting to improve communication. As online communication continues to grow, face to face conversations become less prevalent. Messages can easily be misconstrued over text. Raising awareness of gender differences can contribute to reducing misconceptions of messages, enhancing interpersonal interactions and communication efficiency. Future research should explore these texting behaviors considering additional factors such as cultural influences and personality traits. Broadening the scope of studies such as this can create a more comprehensive understanding of digital communication as it becomes a permanent aspect of our future.

References

Abdulrazaq, A. Gill, S. K., Noorezam, M., & Keong, Y.C., (2012). Gender Difference and Culture in English Short Message Service Language among Malay University Students. 3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 18(2), 67–74

Baron, N. S., Ling, R., Lenhart, A., & Campbell, S. W. (2014). “Girls Text Really Weird”: Gender, Texting and Identity Among Teens. Journal of Children and Media, 8(4), 423–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2014.931290

Ceccucci, W., Peslak, A., Kruck, S.E., & Sendall, P.,. (2013). Does Gender Play a Role in Text Messaging? Issues in Information Systems, 14(2), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.48009/2_iis_2013_186-194

Leap, C., Robnett, R. D. (2011). Women Are More Likely Than Men to Use Tentative Language, Aren’t They? A Meta-Analysis Testing for Gender Differences and Moderators. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310392728

Music, E. (2014). The Do’s and Don’ts of Texting a Girl. The Single Guys Guide to Dating. https://singleguysguidetodating.wordpress.com/2013/11/08/the-dos-and-donts-of-texting- a-girl/

Waseleski, C. (2006). Gender and the Use of Exclamation Points in Computer-Mediated Communication: An Analysis of Exclamations Posted to Two Electronic Discussion Lists. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(4), 1012–1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00305.x