Nisha Porchezhiyan

The present article is a research study about the use of gendered insults while playing Super Smash Bros and Mario Kart. This study consisted of three players, one female and two male playing both of the games and analyzing their conversations to see which gender used “pussy” as an insult more often and what types of triggers each gender had for the word. This paper argues that men use the word “pussy” as an insult more than women while playing video games, typically as either retaliation for when their character gets hit in the game or as a generic insult that is not caused by any action in the game. On the contrary, women typically use “pussy” as an insult only when another player calls them that insult. The results of the study support the thesis and the results align with the conclusions of previous researchers. The data collected implies that the high male frequency of “pussy” might reinforce gender stereotypes where women are seen as weaker than men, because they use female genitalia as an insult for being weaker.

Video Gaming and Swearing

Video gaming is a culture that uses excessive swearing among the players, acting as a means of communication where the use of gendered insults is common. Gendered insults are derogatory words about females or female genitalia, such as “pussy,” “whore,” “sissy,” etc. This study will focus on the use of the word “pussy” while playing the video games Super Smash Bros and Mario Kart. Super Smash Bros is a fighting game where players’ characters battle on a stage, known as the map. Mario Kart is a racing game where players’ characters race each other around the map, or the racetrack. I used a sample of Arizona State college students and transcribed their conversations while playing these games; this type of research will help me explore the distribution of the word “pussy” based on the gender identities of the speakers and the different triggers each gender has when they use “pussy” as an insult. While both genders use “pussy” as an insult, men use it more often than women while playing the Mario Kart and Super Smash Bros and with different triggers for the word: women use it only when they get called a “pussy” by another player, while men use it when their character gets hit/falls off the map, or as a general insult without anything happening in the game.

What research was done before?

Beginning with gendered insults, feminist social constructionist theory argues that using gendered insults and sexual language about females shows male sexual power over women because of the objectification of women (Murnen, 2006). The author argues that men use gendered insults more than women, while women use them less often. What Murnen argued was similar to the results I found in my research with college student gamers, a group that reinforces social stereotypes with the high frequency of swear words, known as “flaming” other players. “Flaming” is insulting a friend as a joke or a tease, with no ill intent behind the insult. This is why most insults said during video games are not meant to be personal insults, but just friendly commentary among friends (Elliot, 2013). The insults used during video games act as a means of communication among the players; video game players use excessive swearing which reinforces stereotypes because players often do not think before speaking while playing video games (Finnegan, 2019).

Specifically, on gendered insults while video gaming, the use of excessive swearing can contribute to gender norm regulation, leading to the frequent use of gendered insults in regular societal discourse (Felmlee, 2019). While this is a broad statement and the findings of this research cannot be extrapolated that extremely, my research does build on the basis of Felmlee’s work.

How was this study designed?

This research project focused on the use of the word “pussy” while playing Mario Kart and Super Smash Bros on the Nintendo Switch. Because I only had three controllers, the sample size was three people: one African American/Portuguese male, one white female, and one white male. The participants knew their conversations during the game would be recorded, but they did not know what I was specifically looking for. For the Mario Kart video game, the participants played Bell Cup, which all three of them decided to be the hardest cup (set of four races). This was chosen because harder games would aggravate the players more, leading to a higher frequency of gendered insults used. For the Super Smash Bros video game, the participants played three rounds (one battle) and the participants were given the flexibility of choosing their own character. All of the games the participants played were recorded from which I pulled excerpts and transcribed to be used as data.

What were the results?

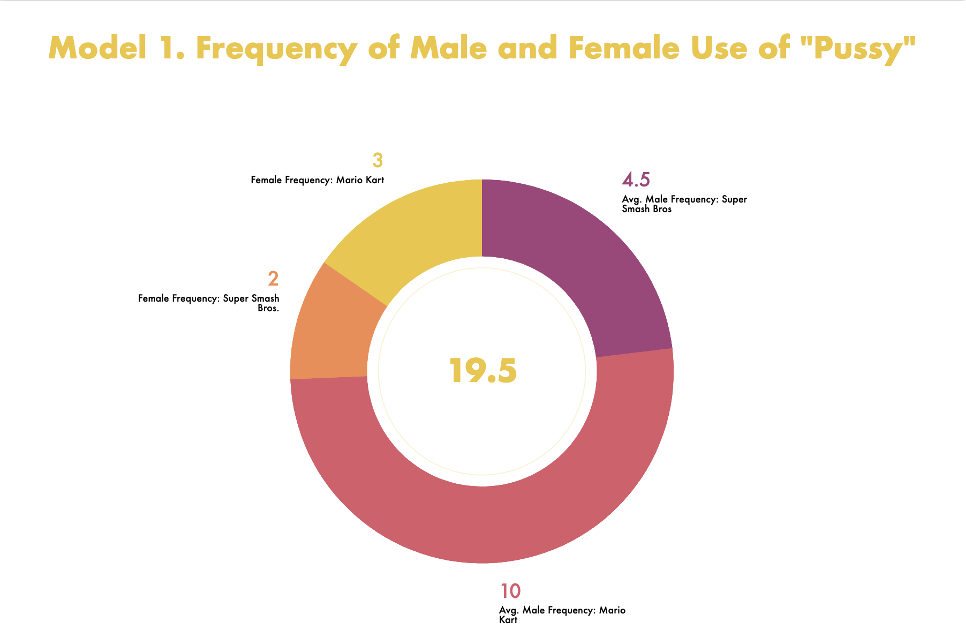

By tallying the frequency of the word “pussy” as an insult, I was able to create a pie chart to visualize the frequency of the male use of “pussy” and the female use. Because there were two males and one female in my study, I averaged the male frequency. As seen in Model 1, the total average male frequency was 14.5 uses of “pussy” and the total female frequency was 5 uses of “pussy.”

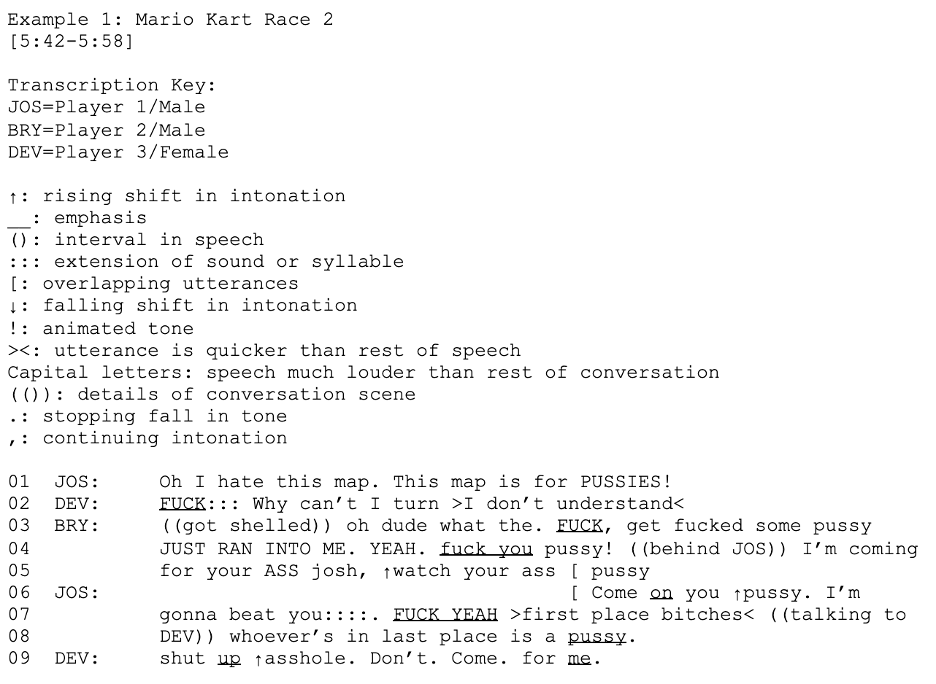

Example 1 is an excerpt from the second race in Mario Kart where “pussy” was used six times. In lines 4,5 BRY (male) gets hit by JOS (male) and calls him a “pussy,” but the other four occurrences of the word were used even though no action occurred in the game (lines 1,3,6,8). This data supports the thesis that for males there are two triggers of “pussy,” either when a character gets hit or when nothing happens in the game. In line 8, JOS calls DEV (female) a “pussy” but she responds by calling him an “asshole” instead.

What do the results mean?

Looking at the pie chart from Model 1, male players used “pussy” at a higher frequency than the female player, supporting my thesis than men are more likely to use the word “pussy” as an insult compared to women. This supports the findings of Murnen’s research and might imply that male use of the word “pussy” is higher because of their positioning in society with more power due to gender stereotypes (Murnen, 2006).

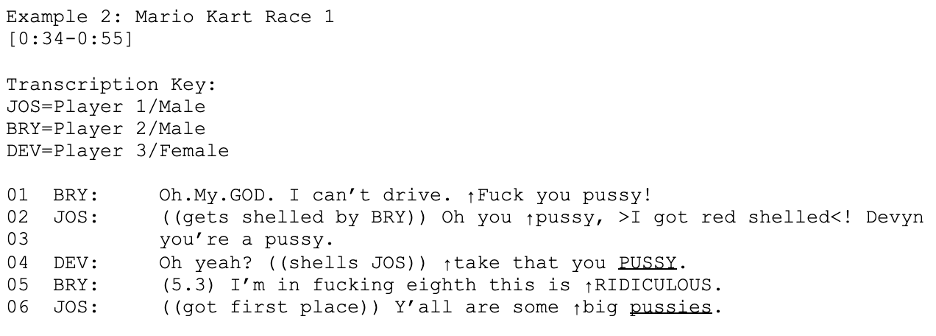

The transcripts from Examples 1 and 2 support my thesis that male use of the word “pussy” has two different triggers, either when their character gets hit or without any action occurring in the game. Moreover, as seen in Example 2, the female player (DEV) only used the word “pussy” after another player called her a “pussy,” but throughout the entire set of games, she never used the word first. This could be because she did not want to use gendered insults due to their sexist nature but might have wanted to fit in with the group which consisted mostly of men. This is supported by Example 1 where DEV opted to use the gender-neutral insult “asshole” instead of “pussy” which might imply that women are inclined to swearing, but do not want to reinforce gender norms and the objectification of females and female genitalia. This contradicts the findings of Ashwell’s research who argues that gendered insults are so problematic because they lack a gender-neutral alternative (Ashwell, 2016).

Ultimately, the research supported my thesis that men use “pussy” as an insult while video gaming at a higher frequency than women, and how women only use “pussy” after they are called the insult.

Some limitations of this study is that the sample size used was very small and cannot be generalizable for the entire population of college-level video gamers. Moreover, there were more males than females in the study, but ideally there should have been an equal amount. The study should also have focused on other types of gendered insults to be able to provide a conclusion on gendered insults as a whole.

Based on these results, for future research, I recommend looking into socio-political beliefs of the participants and whether there is a correlation between their political views and their use of gendered insults.

References

Ashwell, L. (2016). Gendered Slurs. Social Theory and Practice, 42(2), 228-239. Retrieved February 8, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24871341

Elliot, T. P. (2012). Flaming and gaming – computer-mediated-communication and toxic disinhibition. University of Twente (student thesis).

Felmlee, D., Inara Rodis, P., & Zhang, A. (2019). Sexist Slurs: Reinforcing Feminine Stereotypes Online. Sex Roles. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01095-z

Finnegan, J. (2019). Bad language and Bro-up Cooperation in Co-sit gaming. Approaches to Videogame Discourse Lexis, Interaction, Textuality.

Francesca, Thaliakr, Rachel, Robert, Youredoingamazing, Jc, Rose, K. (2018, April 12). Everyday misogyny: 122 subtly sexist words about women (and what to do about them). Retrieved March 18, 2021, from http://sacraparental.com/2016/05/14/everyday-misogyny-122-subtly-sexist-words-women/

Murnen, S. K. (2006). Gender and the use of sexually degrading language. Psychology of Women Quarterly. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00214.x

I’m sorry but… doesn’t the term “pussy” come from the word pussycat? like a scaredy-cat? The insult is always used to express someone who is weak, timid, and/or scared. I’ve always thought that it came from the term pussycat rather than the vagina, and thinking of it as a sexist term is even more sexist.