Mariam Alghamdi

“Man up!”: A phrase that has come to mean “toughen up”. It is a phrase that we still hear, well into the twenty-first century; it is a phrase that even those who deem themselves feminists, myself included, let slip out of their tongues accidentally. The occasional use of such a phrase says a lot about the engraved stereotypical views of men as strong and women as vulnerable in our society. Even in the absence of such a phrase, sadly, such views find a way to shine through. This article studies the representation of women as vulnerable beings and as active participants of conversations, mainly by other male characters, in two American sitcoms from two different eras – Cheers and Brooklyn Nine-Nine. Cheers, which aired in the eighties, revolved around a group of people that frequent a bar. On the other hand, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, which is still airing, revolves around a police precinct in Brooklyn. In order to study such depiction of women, I will specifically be using conversational analysis with a focus on four language units: word choice, pauses, elongation, and emphasis. By investigating such representations of women, I am investigating if there is hope in a society that still uses the phrase “man up”; if the representation of women in American sitcoms has changed enough that young women can feel empowered through watching such shows.

Introduction

The stereotype that women are vulnerable, incompetent individuals that need the guidance of a man in order to move through life has existed for centuries, which comes hand in hand with the dismissal of women’s opinions. This article investigates the representation of women as vulnerable, incompetent beings as well as their contribution to general discourse in two American sitcoms, Cheers and Brooklyn Nine-Nine. The difference in the eras these sitcoms were/are aired during is a key factor to this article since I am interested in the progress of such representation of women through time. As this article will show, Cheers perpetuates and reinforces the categorization of women as vulnerable, incompetent individuals and simultaneously dismisses their contributions to the discourse. On the other hand, Brooklyn Nine-Nine resists such categorization while validating the contributions of women.

Methods

In order to carry out this study, I looked into the first six seasons of Cheers and Brooklyn Nine-Nine. To make the comparison between these sitcoms as fair as possible, I specifically picked situations that were parallel or semi-parallel in both sitcoms. I then analyzed these scenes using conversational analysis with a focus on word choice, pauses, elongation, and emphasis to better understand the role language plays in such representation of women.

Before diving into the findings of my investigation, I will briefly talk about each of the linguistic units I chose to investigate to prevent any confusion throughout the article. When looking at the choice of words, whether it is intentional or not does not matter in my investigation not only because one cannot deduce the intentions of the characters/writers – not to mention the function of intention in scripted data is complex – but also because regardless of intention, the choice of words reflect certain ideologies whether intentionally or not. On the other hand, pauses, can be used to amplify the importance of certain statements as Penelope Eckert and Sally McConnell-Ginet discuss in their book Language and Gender (Eckert & Sally McConnell-Ginet, 2013). Lastly, from Robert E. Pittenger and Henry Lee Smith Jr, elongation, which indicates elongating certain parts of a word, and emphasis can be used to magnify the importance of certain parts of the conversation since they capture the audience’s attention (Pittenger & Smith, 1957).

Results and Discussion

To arrive at effective conclusions, I am comparing Cheers and Brooklyn Nine-Nine by studying two parallel situations. I am also studying a fan favorite scene from Brooklyn Nine-Nine to understand its limitation in resisting the aforementioned representation of women.

The first situation is a discussion regarding a female character by male characters, which take place in the pilot episodes of both sitcoms. In the pilot episode of Cheers, Sumner and his fiancé, Diane are at the bar, where Sam serves them drinks. Sumner is going to leave Diane alone at the bar while running an errand. Sumner asks Sam, a total stranger, to look after his fiancé during that time, clearly indicating that in his absence, the guidance of another man is needed. Sumner emphasizes the words “alone” and “bar” as well as elongate the word bar when he discusses with Sam how stupid of an idea it is to leave Diane there. Sumner’s exact words are shown in Figure 1. This further indicates Diane’s need of a man’s guidance.

On top of that, Sumner chooses imperative words such as “sit” and “chat”, when telling Diane what to do as he runs his errand. This indicates that he is not suggesting how Diane should spend her time, but rather giving her directions. This is further echoed by Sumner’s body language, which is shown in Figure 2, as Sumner guides Diane to the chair by holding her shoulders and directing/moving her towards the chair.

Please note that Diane’s annoyed face at the first image in Figure 2 is not a reaction to Sumner’s words but a reaction to a snarky comment Sam made.

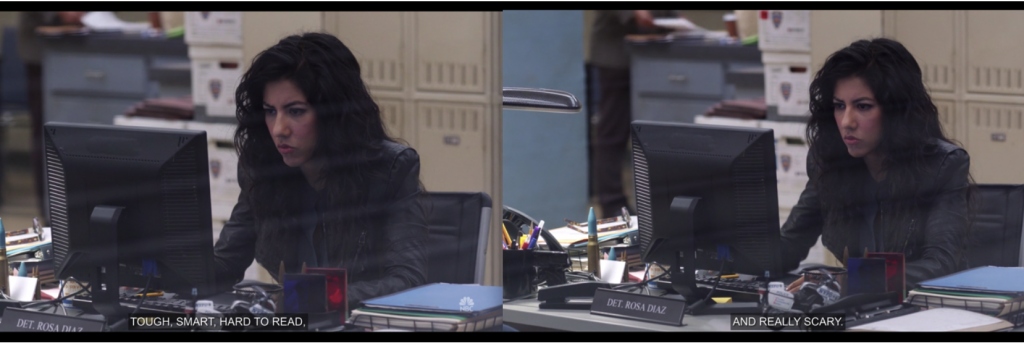

In the parallel scene in the pilot of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Sergeant Terry tells the new precinct’s captain about his detective squad. In his introduction, he uses word choice, emphasis, and elongation to portray one of the female detectives, Rosa, as a strong character. Terry uses words such as “tough”, “smart”, and “scary”, which portrays Rosa as anything but incompetent and vulnerable. Terry also adds the word “really” before scary elongating and emphasizing it, which indicates that Rosa is not only scary but terrifying.

The second parallel situation is the discussion of the sexual harassment of a female character. In Cheers season 2 episode 3, Diane is upset about constantly being harassed by potential employers and complains about it. Even though Sam tries to be helpful, his choice of words is poor and reflects a lack of understanding regarding the severity of the situation. He uses phrases like “lighten up” and even cracks a joke while trying to be supportive as he says, “Sometimes I’m just ashamed to be a guy, but if I made the switch now I’d have to buy a whole new wardrobe.” He even laughs amusingly at his joke.

Sam’s lack of understanding and disregard to Diane’s feeling is further amplified by his sexual treatment of Diane. At a point in the conversation, Sam expressed some anger regarding Diane’s situation, but his use of emphasis illustrates that his anger is misdirected. His angry moment is shown in Figure 5.

Sam emphasizes the words “those”, “my”, and “sex object”. This emphasis indicates that he is angry that other men dare treat his women in a sexual way. His use of emphasis implies an anger relating to his ego and his sense of ownership over Diane rather than Diane’s mistreatment. Not to mention his use of the word “squeeze” when describing Diane sexualizes and objectifies her. In this way, Diane’s contributions, her complaints about her sexual harassment, is not being validated by Sam.

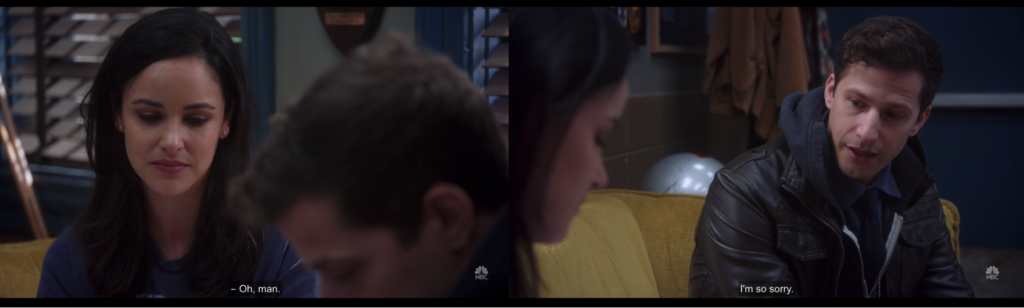

In Brooklyn Nine-Nine in season 6 episode 8, when Amy, a female detective, discusses her sexual harassment experience with her husband Jake, another detective, the response is quite different. The contrast is not only shown through the fact that no jokes whatsoever take place during this scene, unlike in Cheers, but it is also shown through the use of pauses and through Jake’s replies. Amy’s retelling of her experience was filled with long pauses, ones that exceeded one second. These pauses indicate two things. First, they elevate the importance of Amy’s statement. They allowed for the severity of the situation to sink in; for Amy’s thoughts to stay a little on the floor for the audience to subconsciously or consciously dissect them. Second, they highlight Jake’s support as he did not try to talk during these pauses even when he had more than enough time to talk. Not to mention, Jake only spoke two times during Amy’s retelling which is shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

His words themselves show extreme support as he treats Amy as a fellow human – unlike how Sam objectifies Diane in Cheers – even if he does not completely understand her suffering, but his support is shown in different ways as well. Jake even spoke in a low volume in both times, suggesting either an attempt to sound gentle at the news of such pain, uncertainty in what to say, or both. He even spoke quickly the second time which could suggest his frustration at the situation his wife has been through even if he doesn’t relate as well as his desire to not take too much time away from his wife. Jake’s support is emphasized by his facial expressions throughout the times he spoke – in Figure 6 and Figure 7 – as well as throughout the times Amy was speaking, which is shown in Figure 8.

Jake’s support through his silence and facial expressions and such reflects that while he may not understand what Amy is going through, he supports her and validates her contribution.

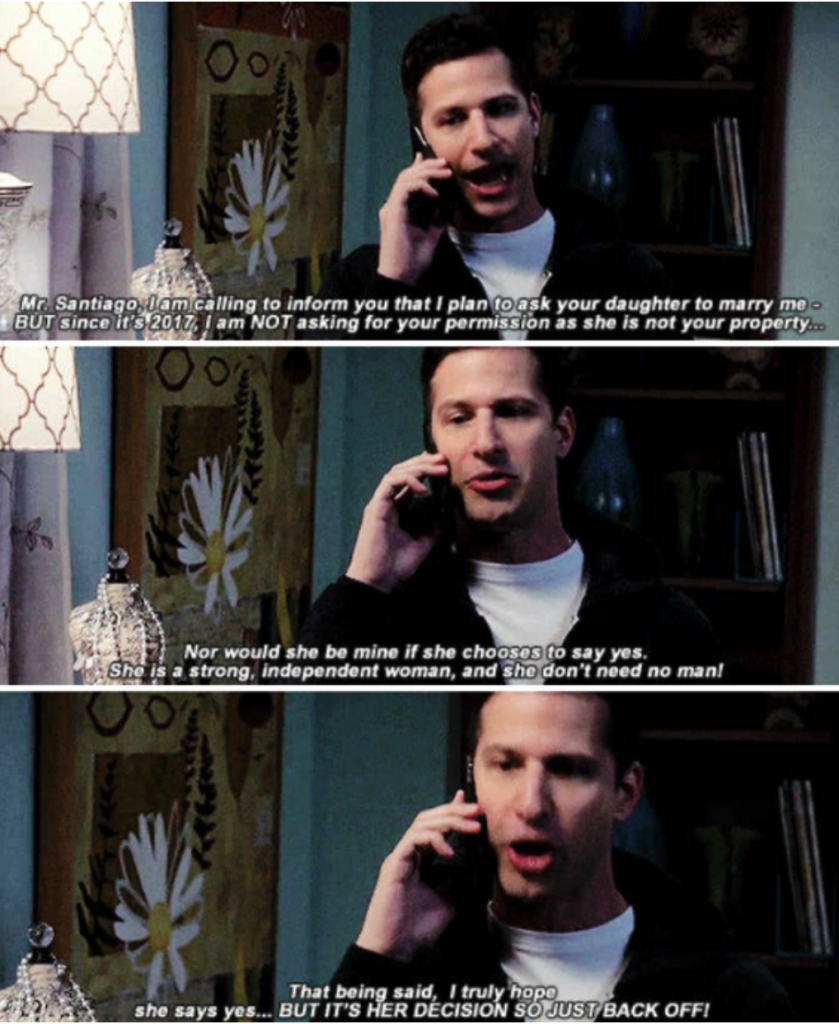

Last but not least, I will study a scene well loved by many fans of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, which takes place in season 5 episode 4. Before Jake proposes to Amy, he leaves her father a voicemail. This scene is shown in Figure 9.

This scene is well loved by many fans because it refutes the categorization of women as vulnerable, incompetent and in need of a man’s guidance. This is clear through Jake’s choice of words as he describes Amy as “strong” and “independent”. He even explicitly says that “she don’t need no man”. However, an important thing to note that lovers of this scene tend to forget is that Jake still felt the need to call Amy’s father. It was not in a way to inform the family either, because if it was he would not have highlighted the fact that he was not asking for permission. Not to mention, he would have called her mother as well, and there was no indication at all that he ever did. So, while this scene does in fact refutes the categorization of women as in need of a man’s guidance, it also reflects the fact that such categorization is not completely wiped out. In a way, this scene perpetuates such stereotypes as it highlights that even though Jake does not ask for permission, the idea still floats in his mind and he still is expected to inform Amy’s father. This ties back to Raymond’s idea that the representation of categories in scripted shows can in fact perpetuate stereotypes even when it tries to combat them (Raymond, 2013).

In order to reach a conclusion confidently, I analyzed one other parallel situation, which was a marriage proposal in both sitcoms. To grasp the comparison between the two sitcoms in more depth and for more details, see the FULL PAPER which includes transcript and linguistic analysis of the interactions discussed in this article as well as the additional parallel situation.

Conclusion

While analyzing scripted data using conversational analysis, in this case Cheers and Brooklyn Nine-Nine, does not help us better understand human beings, Chase Raymond argues that applying conversational analysis on scripted data is fruitful since it helps us understand society’s interpretations and indexation of certain categories (Raymond, 2013). My findings in this article indicates that society’s view and interpretation of women has in fact changed from the eighties to today, at least in those two sitcoms. From the analysis of the two parallel situations above, we can see that language aids in the depiction of women as vulnerable, incompetent being that need a man in the older sitcom Cheers. Language is also used to dismiss the contributions of women in Cheers as analyzed above. This representation of women reflects a similar societal view of them as vulnerable, incompetent individuals whose contributions are not taken seriously. On the other hand, language helps women contribute to the general discourse in the more modern sitcom Brooklyn Nine-Nine as well as aids in refuting the stereotypes of women as vulnerable beings. Once again, this representation of women reflects a similar societal view of them as strong, competent individuals whose contributions are not only taken seriously but supported as well. It is important to note that while the representation of women has progressed, the progress is not as simple, as linear as saying that the more modern sitcoms tend to be resist all stereotypes and validate all women’s contribution. As analyzed in the fan-loved example, some attempts at resisting certain stereotypes comes hand in hand with perpetuating said stereotypes.

Lastly, while this article does not aim to make any statements regarding the effect of such representation on society, almost everyone in today’s society agrees that representation matters. The way someone’s categories are represented in the media including sitcoms affects their self-esteem as I know from experience and as I am sadly sure many others do as well. Hence, even though more studies are needed to make a firm conclusion, it is fair to assume that the representation of women could help encourage or discourage young women, and fortunately it seems like the representation of women in American sitcoms is moving in the right track even if it comes with limitations.

References

Angus, Kat. (2017, November 3). 21 Times Jake and Amy’s Love On “Brooklyn Nine-Nine” Made Us Melt. Buzzfeed. https://www.buzzfeed.com/katangus/peralta-and-santiago-4eva

Eckert, P., & McConnel–Ginet, S. (2013). Language and gender (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press.

Raymond, C. W. (2013). Gender and Sexuality in animated sitcom interaction. Discourse & Communication, 7(2), 199–220.

Robert, P.E. & Smith Jr, H.L. (1957). A Basis for Some Contributions of Linguistics to Psychiatry. Psychiatry, 20(1), 61-78.