Alexa Waldman, Teresa Humbert, Morgan Moseley, Luke Kim

Prior to joining greek life, I was exposed to the stereotype that sorority girls were mean and hierarchical whereas fraternity boys were friendly and laid back. I was told to be prepared for girls to make comments that impose their superiority to make me feel small. However, during rush, I found that I was addressed with respect in every conversation. The girls always made sure to use words like “affordable” instead of “cheap,” and constantly parroted that slang phrase “Panhel love,” which means that each sorority chapter has love and respect for the rest.

On the other hand, boys who had gone through fraternity recruitment expressed that they were not treated with respect and that the older members made sure to establish power imbalances. They would use words like “facey”, meaning that someone is good looking enough to be in the fraternity and “moldable”, meaning that someone has good traits but can become better if he joins the fraternity. They used these terms in front of the potential members to impose their authority.

In our project, we studied slang used by sorority and fraternity members in order to determine how patterned language usage has the power to create and perpetuate gendered power imbalances and interorganizational hierarchies.

Introduction and Background

Greek Life, which dates back to the 18th century, is a significant part of campus communities all across America. While many individuals see Greek life as a way to gain friendships and connections, the portrayal of Greek life in media, such as film and on social platforms, has suggested power imbalances within the institution and has casted a negative light on the organizations. Many stereotypes portray sorority girls as snobby and clicky, and portray fraternity members as inclusive and laid back. Our group was interested in investigating if there is truth behind these narratives.

We addressed the gap in patterned slang use between sorority and fraternity members to determine how speech can point to and maintain power imbalances. We predicted that because members of each individual organization share common language patterning, slang could be used to reinforce group identities. Moreover, we predicted that differences in communication practices between fraternities and sororities (as seen through slang) reflect and reinforce underlying gender power imbalances.

When taking a closer look, we found that there are flaws in the stereotypes surrounding Greek Life. In fact, our preconceived notions that sorority girls are clicky and enforce power imbalances, and that fraternity members are more inclusive and have less of a hierarchical structure were not supported by our evidence. Instead, by analyzing speech patterning in these

institutions, we found that fraternity members use slang to create a hierarchical structure within their chapter, compete with other fraternities, and facilitate gender imbalances of power between sororities and fraternities. On the other hand, we found that sorority members tend to have a symmetrical power dynamic within their chapters and promote friendship and inclusion with the other sororities through their use of slang. Overall, our research challenges the stereotypes that surround Greek life, revealing the flaws in common narratives about the power dynamics within Greek Life communities

Methods

Our research was conducted in sorority and fraternity houses over the course of a month. Each person in our group sat down with members of Greek Life for interviews that lasted about 20-30 minutes each. The interviewer asked open-ended questions in order to allow the sorority and fraternity members to freely explain their experiences. In the interviews, we asked questions such as “can you describe the slang words used most in your chapter? How does slang suggest/ create power imbalances? What topics does your slang refer to the most?” Some questions differed for sorority and fraternity members as we wanted to understand how each institution perceived the other. We asked sorority members what slang they thought fraternity members use the most and what topics they believed this slang surrounded. We asked fraternity members the same questions about sorority members.

We also focused on understanding relationships within and between sororities as well as within and between fraternities. For this reason, we interviewed people from different grades, from different chapters, and with different positions of power. For example, we questioned the president of a fraternity along with a sophomore and a freshman. We similarly talked to members on the executive boards of different sororities, and interviewed seniors, juniors, sophomores, and freshmen in these same organizations. We interviewed people in different positions/ grades in two fraternities and three sororities.

Interviewing a diverse range of people within multiple chapters of both sororities and fraternities gave us a multifaceted picture of the contexts in which slang is used, how slang is used, why slang is used, and the effect of slang. This researching process specifically gave us insights into how slang has different purposes and effects when used by sororities and fraternities.

Results and Analysis

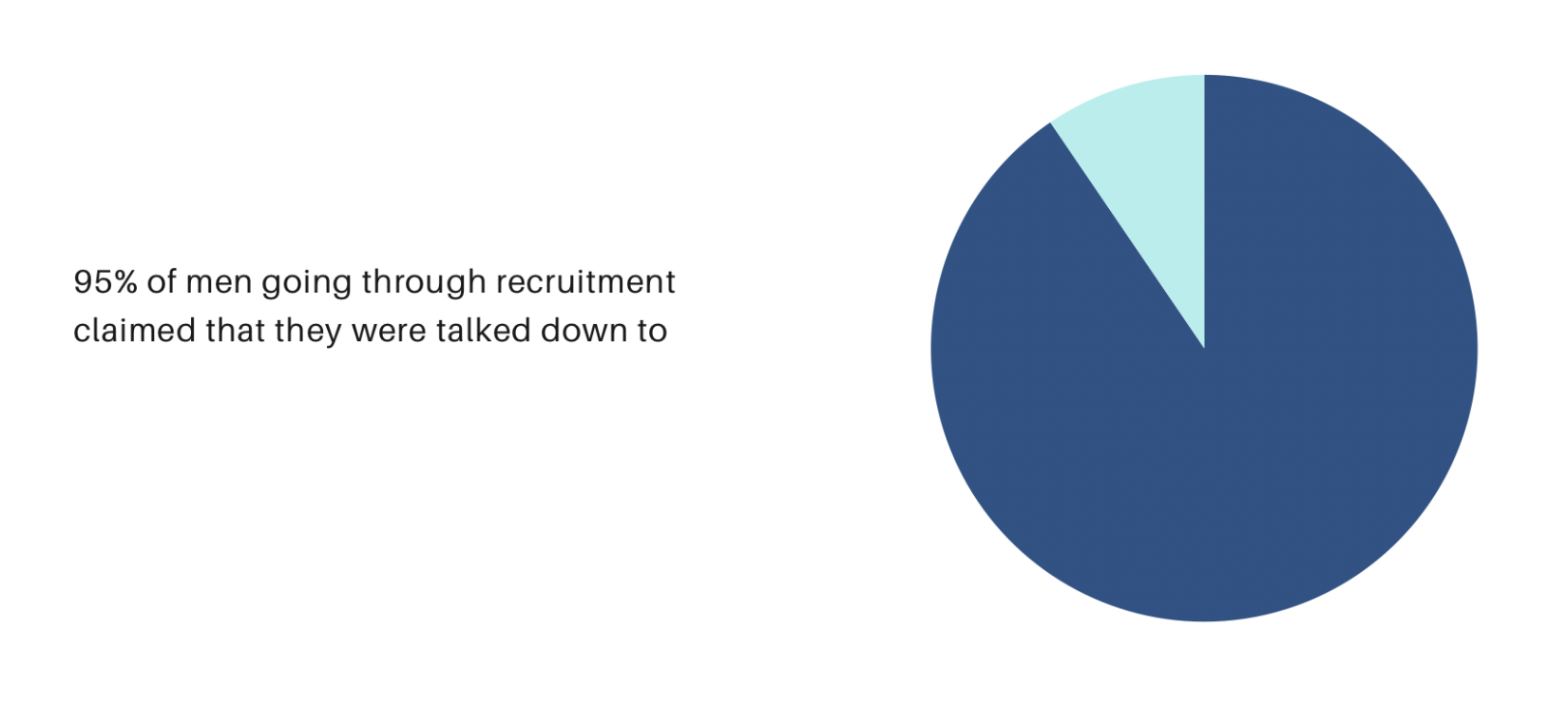

Our research demonstrates how sorority members harness slang to facilitate an environment of inclusion and harmony within and between sorority chapters. On the other hand, we found that fraternity members utilize slang to create power imbalances within chapters, between chapters, and between fraternities and sororities. Many fraternity brothers discussed that power imbalances within their organization were especially evident in the difference of social status between new members and brothers that had already been initiated into the chapter. For example, new members are called “pledges” in every fraternity. This slang word is

used to emphasize their inferiority to the rest of the boys in the chapter. In one chapter, new members are collectively called “the stinkys” to signify that they smell bad, a further example of how official members degrade their new members. 95% of the fraternity members we interviewed said that they had experienced being talked down to while they were going through the recruitment process.

Figure 1

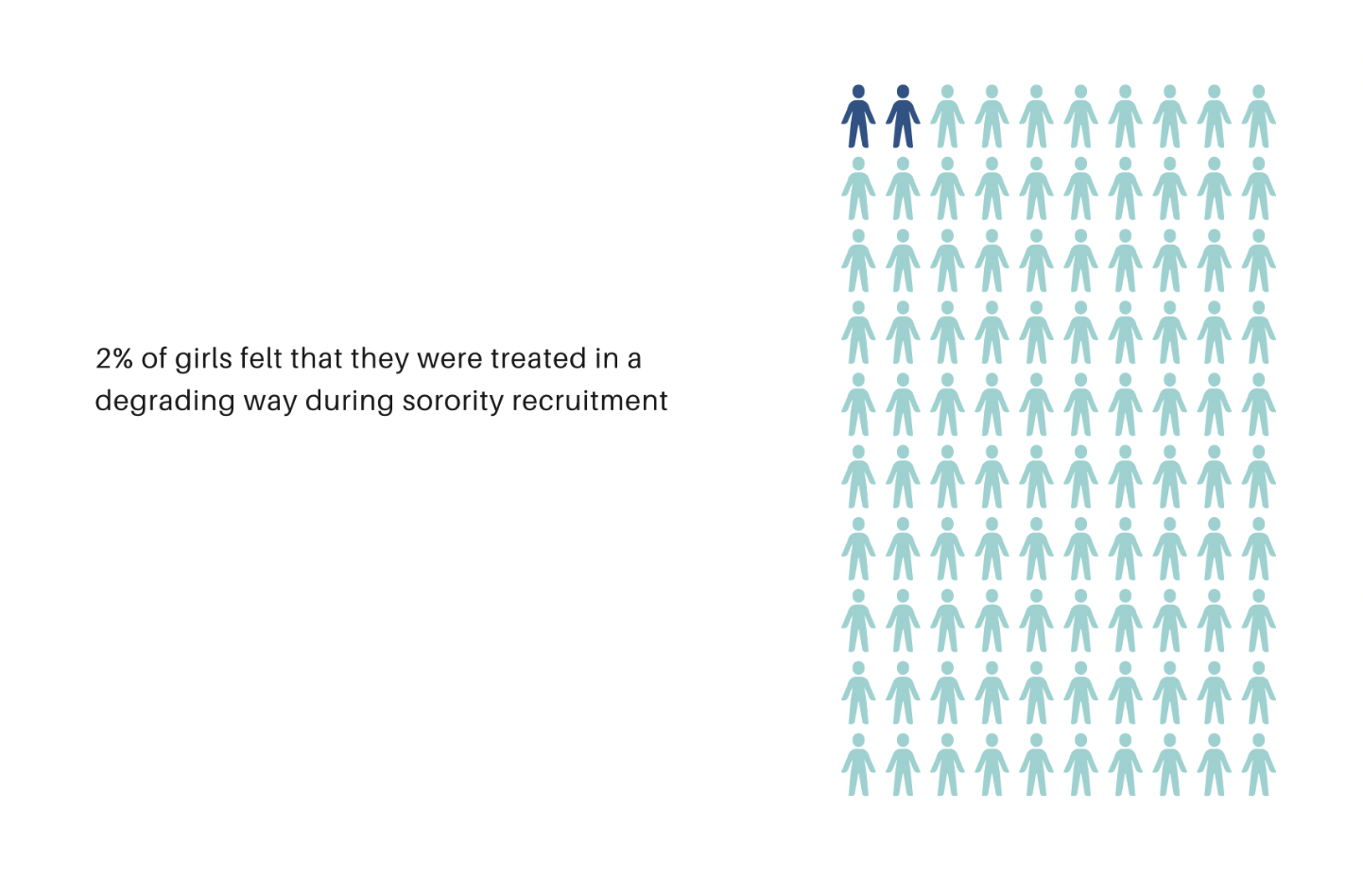

On the other hand, many sorority members expressed how they did not feel the pressure of power imbalances during recruitment or within their chapter. For example, active members in the sorority Alpha Phi were calling the new members “Phisters” – a chapter-specific slang word for “sisters” — from the moment that they got their bid. Furthermore, even though new members are typically called “pledges,” which has connotations of inferiority, sororities are in the habit of abbreviating “pledge class” to “PC” in order to rid the slang of its power to demean new members. While fraternity brothers relinquish the title of “pledge” the moment they are initiated as members, sorority members continue to refer to their “PC” in terms of the community and cohesiveness of each group that joined the sorority at the same time. In interviewing sorority sisters, we found that only 2% of members felt that they were talked down to during recruitment.

Figure 2

Through our interviewing process, we also encountered slang that perpetuated gendered power dynamics between sororities and fraternities. Our data suggested that this type of slang is used mainly by fraternity men towards or about sorority members. For example, fraternity men use derogatory slang words such as “ran through ” and “been around” to describe women that they want to demean for being (what they consider to be) overly sexually active. Sorority women expressed that when fraternity men act in the same way, it is considered normal and there are no slang words used to discuss them in a negative light. This example demonstrates how slang is used to perpetuate power imbalances that are prevalent throughout the country within gender-specific institutions.

Discussion and Conclusions

Overall, our research suggests that sororities have a more egalitarian and encouraging culture whereas fraternities have a clear hierarchical structure and competitive environment. These findings add to our understanding of gendered power dynamics in social organizations. The hierarchical nature of fraternity culture is reflected in the slang they use, which highlights the competitive environment and the importance of rank and authority.

Our research indicates that these organizations’ internal cultures are significantly shaped by their communication patterns as members of fraternities and sororities speak in ways that both reflect and perpetuate their respective power structures. Fraternity men use slang to enforce power imbalances which produces a feedback loop: the more slang is used to create imbalances, the more imbalances exist, and thus the more this slang is used. On the other hand, sorority women utilize slang to establish a cohesive and inclusive environment, and this environment breeds further use of unifying speech patterning. Additionally, our study emphasizes how crucial it is to evaluate media representations of social groupings and prejudices as our research contradicts a widely held presentation of these organizations.

Our research is important in bringing awareness to power imbalances and injustices that go unnoticed or are simply accepted by fraternity members. Our findings may incite fraternity members to evaluate their slang usage and strive to use language that facilitates a more equal, safe, and positive environment in the future. One possible solution is the implementation of workshops and training sessions focused on inclusive and respectful communication within Greek organizations. Educating members about the impact of language can foster a more supportive atmosphere, reducing hierarchical behaviors in fraternities and enhancing the positive dynamics in sororities.

References

Appalachian State University. (2024). Fraternity and sorority life. History of Fraternities/Sororities. https://fsl.appstate.edu/history-of-greek-life

Handler, L. (1995). In the Fraternal Sisterhood: Sororities as Gender Strategy. Gender and Society, 9(2), 236–255. http://www.jstor.org/stable/189873

Izmaylova, G. A., Zamaletdinova, G. R., & Zholshayeva, M. S. (2017). Linguistic and social features of slang. International Journal of Scientific Study, 5(6), 75-78. 10.17354/ijssSept/2017/016

McLemore, C. A. (1991). The pragmatic interpretation of English intonation: Sorority speech (Order No. 9128305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303946119).https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/pragmatic-interpretation-en glish-intonation/docview/303946119/se-2?accountid=14512

Morgan, Emma, “Losing Yourself: Cults, Greeks, and Sociological Theories of Self and Identity” (2021). Honors Program Theses. 138. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors/138

Rowan University. (2024). “Benefits.” Benefits of Greek Life. https://sites.rowan.edu/oslp/greekaffairs/benefits/

Scott, John Finley. (1965). “The American College Sorority: Its Role in Class and Ethnic Endogamy.” American Sociological Review, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 514–27. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2091341

Thompson, Bailey Airs. (2017). “#Sorority girl: The Sorority Socialization Process through the Construction and Maintenance of the Individual and Chapter Sorority Identity.” DSpace Repository, 1-15. ttu-ir.tdl.org/items/742e3cc2-4d41-4b94-9efe-018b9bf98f54.