Kara Bryant, Nina Matloob, Sophie Reynoldson, Kayla Sakayan, Makayl Walsh

Deafening screams, fearful gasps, and streaming tears are all common characteristics displayed in one of film’s most prominent genres: horror. Horror films frequently portray situations like violence, villains, and monsters, naturally eliciting distress from the characters involved. Often, the characters exhibit various distress behaviors, including cries, shrieks, and screams. Given recent efforts to advance nuanced female representation in media, has feminism infiltrated the modern horror genre? A prevalent theme in classic horror has involved women being stereotyped as the submissive and helpless victim. Our research question analyzes how horror films perpetuate gender stereotypes through the portrayal of how men and women communicate distress. We created tallies for the instances of cry-behavior in 10 films ranging from 1960-2023. The results aligned with our hypothesis, which is that women exhibit more cry-behavior than men in horror films. In the films post 2000, the gap between cry-behaviors for women and men is smaller than in films made prior. This article discusses how gender ideals have been reinforced or uprooted, and the role of emotionality in horror films.

Introduction

How do horror films perpetuate gender stereotypes of weakness through the portrayal of how people communicate distress? Analyzing how people communicate distress in horror films through cry-behavior, which is often linked to weakness, instability, and over-emotionality, (Bylsma et al. 2019) is a valuable way to measure how horror films underpin the notion that women are more emotional than their male counterparts (Brescoll, 2016). We aim to assess the portrayal of gendered stereotypes by identifying the difference between how men and women communicate distress in horror films and analyzing how these portrayals of gendered behavior have evolved. Through developing an awareness of the media’s subliminal messaging that socializes our views of gendered behavior, we can uncover how to combat the internalization and perpetuation of these stereotypes and cultivate a more feminist lens in film.

Background

Our target population for this study is men and women in horror films. This film genre has become synonymous with the victimization of women. Women are often the victims while men are usually the primary perpetrators of violence, illustrating strong gender imbalances (Manaar Kamil & Jubran 2019). Another stereotype that has been identified in horror films is that women who are sexualized are most often killed first, sending the message that females who express sexuality should be punished (Cowan et al. 1990). Women are portrayed as naive, clueless, and leading themselves to their murder (Manaar Kamil & Jubran 2019).

While much research has been done on women as victims in horror films, few researchers have examined the specific ways distress is portrayed in these films. This leads us to the aspect of communication that we wish to investigate: how people communicate distress through signs such as screaming, crying, and pleading to find the difference between how men and women are portrayed as communicating distress in horror films. Moscozo (2016) found that the horror genre may be shifting away from the defined stereotypes of women as submissive victims. Therefore, our aim is to assess if the ways gendered portrayals of distress in horror films have also evolved over time.

Methods

We hypothesize that 1) women will demonstrate more cry-behavior than men and 2) films made in the last decade (2013-2023) will show men and women displaying cry-behavior more equally than films from past decades. Each researcher watched two films defined by the “horror” genre, took notes, and tallied how the characters communicate distress and the frequency in which they do so. Five of these films were released after 2014, while the other five films were made prior to 2000. These films include: Psycho (1960), Carrie (1976), Halloween (1978), Scream (1996), Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), Happy Death Day (2017), Get Out (2017), Us (2019), Pearl (2022), and Five Nights at Freddy’s (2023). We agreed that these films embodied the cultural zeitgeist in their respective times, making them indicators not only of popular horror but cultural moments in film. Our sample includes films with lead characters both white and non-white to minimize race as a confounding variable. We included films led by men and women, with prominent characters of both genders represented.

We coded “cry-behavior” in these films based on the characteristics outlined by Gračanin et al. (2014), including tear production, distress vocalizations, and sobbing. Our group defines distress vocalizations as: shrieks, screams, and gasps while excluding “grunts” as they are more closely identified with pain than distress. We all watched a scene from the film Scream (1996) and individually coded it. Afterwards, we compared our results to ensure our method for identifying cry-behavior was consistent before tallying cry-behaviors in each film. For example, we concurred that a continuation of hyperventilation for multiple minutes counts as one tally, but a sudden gasp during that period would count as two.

Results

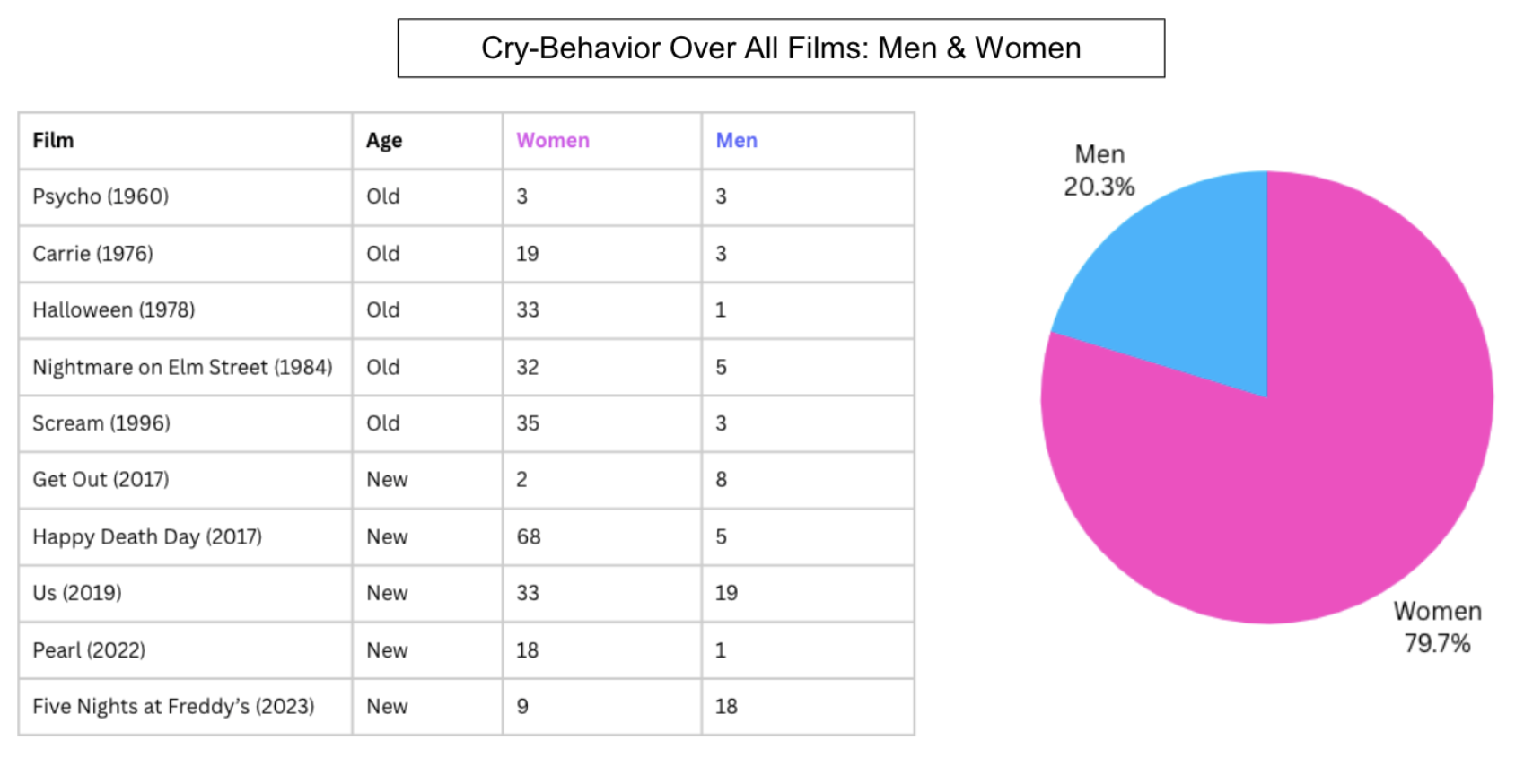

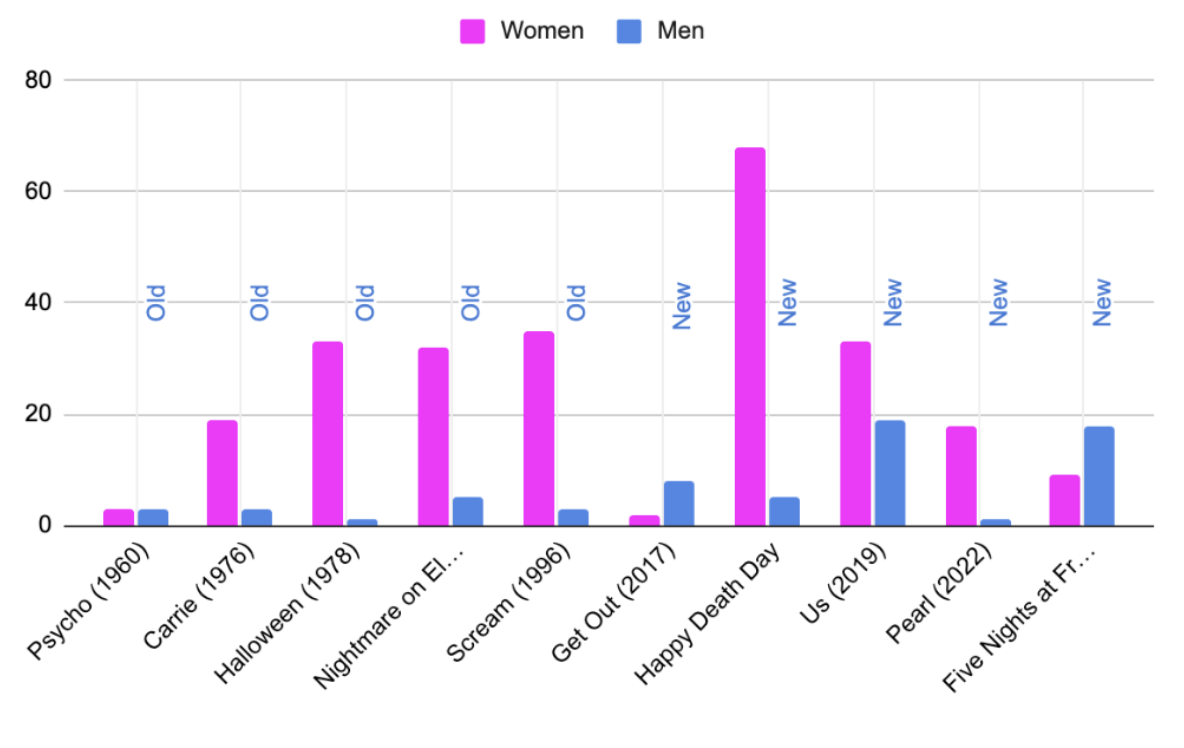

Women in horror movies exhibit more cry-behavior than men. Women demonstrated cry behavior 252 times across older and newer films. Men demonstrated cry behavior 64 times. Thus, in the 316 times cry-behaviors were exhibited in all of the films combined, women represented 79.75% of cry-behavior while men accounted for 20.25%.

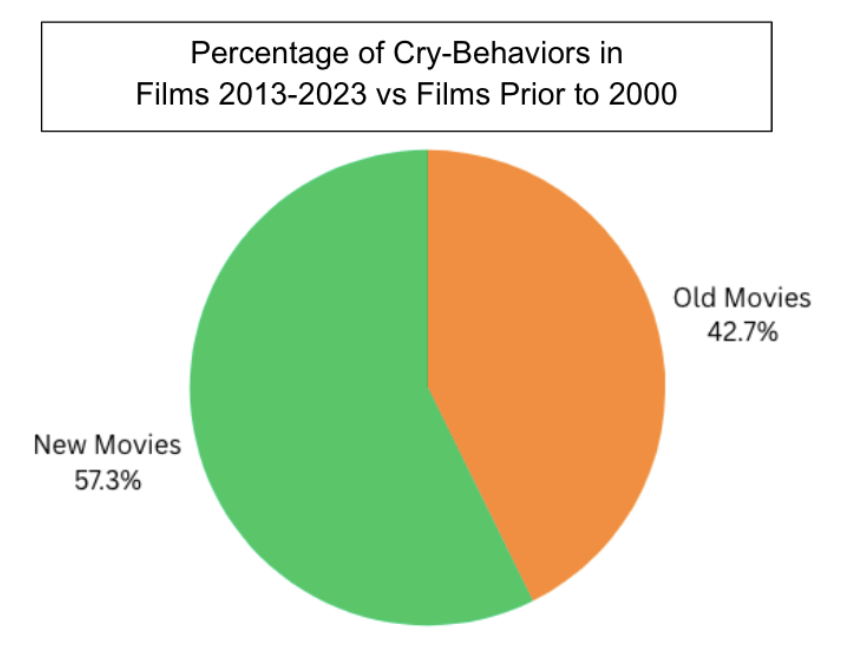

New horror films (those made in the past decade) present more cry-behavior than old horror films (those made before the year 2000) across both genders. New horror films demonstrate 134% more cry behavior.

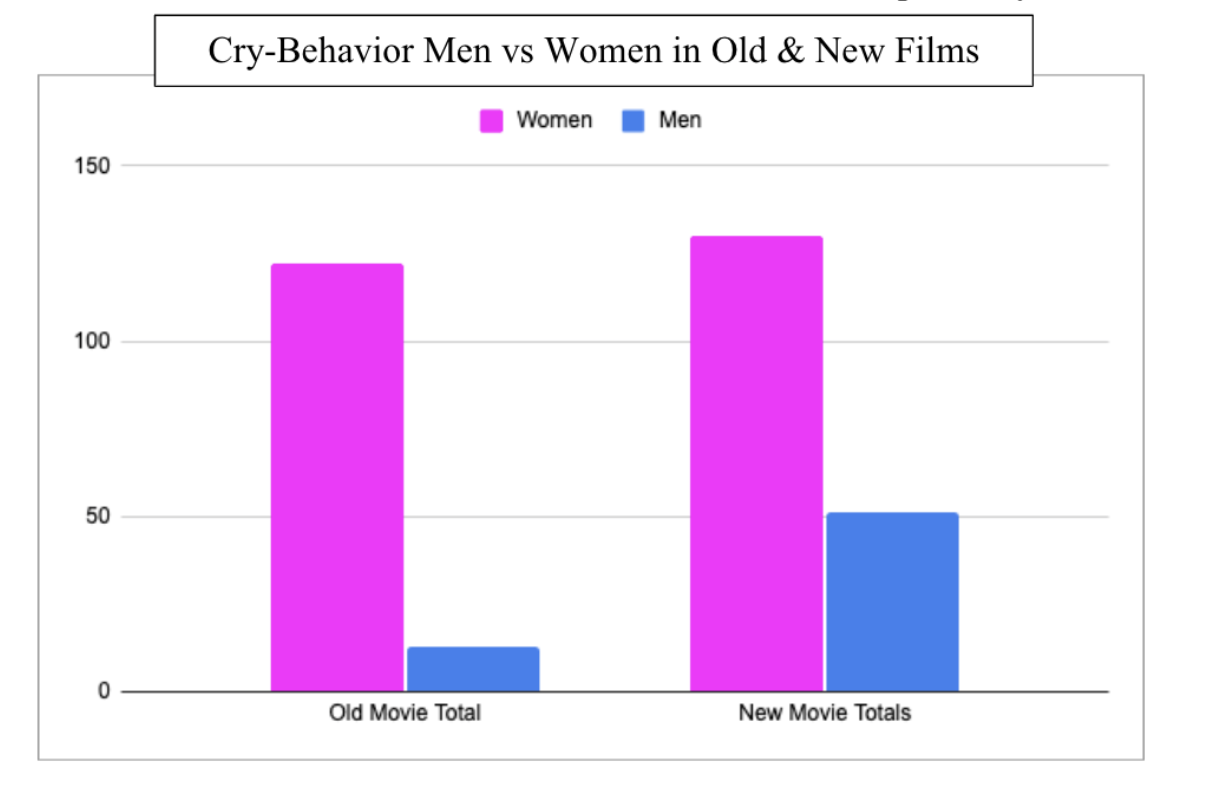

Women in horror movies created before 2000 demonstrate cry behavior significantly more than men. In the 135 times cry-behavior was demonstrated in Psycho, Carrie, Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street, and Scream, women accounted for 122 of those instances, and men only 13. Thus, women represented 90.37% of cry behaviors while men represented 9.63%. Women in horror movies created after 2000, specifically within the last decade, continue demonstrating more cry behavior than men. There were 181 demonstrations of cry-behavior in Get Out, Happy Death Day, Us, Pearl, and Five Nights at Freddy’s combined. Women exhibited cry-behavior 130 times and men 51 times, or 71.82% and 28.18% respectively.

Discussion

Overall, the results support our hypotheses. Women in horror films across past and present decades exhibit significantly more cry-behavior than men, confirming our first hypothesis. Nonetheless, even though women exhibit more cry-behavior than men, the gap is smaller in films produced in the last decade. This highlights strides towards a more equal/feminist lens in films and confirms our second hypothesis. These findings are indicative of how horror films perpetuate stereotypes of women as excessively emotional and weak. Our findings also support the topic of men being conditioned to restrain their emotions as a signal of masculinity. Interestingly, films created in the last decade had more instances of cry-behavior across both genders, which may indicate the audience’s appetite for greater emotional intensity in the films they watch. However, this may also be influenced by confounding variables such as the average runtime of films increasing in recent years.

Overall, female characters typically exhibit cry-behaviors in times of distress and danger, reinforcing the stereotype that women are overly emotional, weak, and unstable. Women display the most cry-behavior in the form of sobbing, screams, gasps, and pleading. Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) plays into the trope of women expressing cry behavior in moments of vulnerability and weakness when they are attacked while bathing, sleeping, or cornered in isolation by the killer. In Psycho (1960), the only time a male character exhibited cry-behavior was while they were being chased and dressed as a female.

Films from the last decade display the lead female character as a killer who is motivated by her fragile and excessively emotional state. In Pearl (2022), Pearl is the sole perpetrator of violence in the film and conveys a range of emotions from rage to sadness; however, her capriciousness may contribute to stereotypes of women as unable to control their emotions since she tends to kill on a whim of rage. Most of her cry-behavior was coded for sobbing. Similarly, in Carrie (1976), the main character first expresses cry-behavior in connection to her femininity when she gets her first period in the female locker room. She exhibits cry-behavior when being targeted by students and her religious mother for her submissiveness and changing female body. Once Carrie becomes the tormentor, her cry-behavior ceases as she watches her classmates cry and scream. In contrast to modern horror films such as Pearl, Carrie gains autonomy once she sheds her emotional disposition.

The situations where cry-behavior is exhibited shift from responses of distress, to expressions of strength in modern films. For example, in the film Happy Death Day (2017), the main character, Tree, exhibits cry-behavior in states of frustration and anger rather than expressions of helplessness and defeat. In Us (2019), the lead character, Addy, is depicted as excessively emotional by her husband who complains that she overreacts. Nonetheless, Addy exhibits strength when she fights the killers. Addy utilizes cry-behavior most frequently during physical encounters, such as stabbings, beatings, and burns, a response to overcoming physical pain rather than fear. Her children exhibit cry-behavior while being held by Addy, which supports how Addy maintains strength and resilience despite the pain.

Interestingly, modern horror also depicts female rage and instability as tools for female characters to weaponize. Rose, the female lead and perpetrator in Get Out (2017), does not exhibit cry-behavior in reaction to physical pain. She reacts with laughter and retaliates by inflicting pain onto others. Rose uses cry-behavior to weaponize her white femininity, playing into the stereotype of the damsel in distress to protect herself from who she believed were the police coming to “rescue” her. Modern films such as Get Out show how the female perpetrator might use her emotions to shift blame onto the male victim. In contrast to female horror representations, the male lead, Chris, does not sob when he is attacked. He downplays and internalizes his cry-behavior through gasps, hyperventilating, and shedding an occasional tear.

Conclusion

Although the representation of women as weak in horror films has lessened, women are still more likely than men to be depicted as unstable and excessively emotional. Modern horror films are beginning to undermine traditional notions of feminine vulnerability and have morphed emotional pain into either a catalyst for vengeful violence or fierce protection. As we work to unlearn societal understandings of emotion as a form of weakness, men demonstrate cry-behavior in times of distress. While improving, the gender imbalance of how men and women communicate distress in these films persists.

References

Brescoll, V. L. (2016). Leading with their hearts? How gender stereotypes of emotion lead to biased evaluations of female leaders. the Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.02.005

Bylsma, L. M., Gračanin, A., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2019). The neurobiology of human crying. Clinical autonomic research: Official journal of the clinical autonomic research society, 29(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-018-0526-y

Cowan, G., O’Brien, M. (1990). Gender and survival vs. death in slasher films: A content analysis. Sex Roles, 23, 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289865

Gračanin, A., Bylsma, L. M., & Vingerhoets, A. J. (2014). Is crying a self-soothing behavior? Frontiers in psychology, 5, 502. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00502

Manaar Kamil, S. & Jubran, H. S. Y. (2019). The representation of women in the horror movies: A study in selected Horror movies. Communication and Linguistics Studies, 5(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.cls.20190501.13

Moscozo, R. D. (2016). Language in Postmodern Horror: Shifting Away from Stereotype to Heroine. Colloquy, 12, 66-86.

Mundorf, N., Weaver, J., & Zillmann, D. (1989). Effects of gender roles and self perceptions on affective reactions to horror films. Sex Roles, 20(11), 655–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288078